GUI History Abridged

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nibbles & Scribbles; 1985-1987

No. 4 June 1985 sufrmiLJwnucnr mar LESCRIPT FOR IBM-PC The big news in this issue of Nibbles & Scribbles is In addition to the 50 programmable function keys that the release of the IBM-PC and TANDY-2000 version of LeScript now gives you on your IBM-PC, there are also LeScript. February 25, 1985 was the official release date 72 PROGRAMMABLE CHARACTER KEYS. These are the foreign of this product. language characters in the IBM-PC character generator ROM, plus a few more scientific and Greek characters to round out This version of LeScript works on the IBM-PC, IBM-XT, the number to 72. The way to get one of these characters to TANDY-2000, TANDY-1200, TANDY-1000, and any IBM-PC exact appear on the display is to simply hit one of the look-alike. Either color or monochrome monitor adaptors can alpha-numeric keys while holding down the <ALT> key or the be used (color looks superb). Either parallel or serial <ALT> and the <SHIFT> keys. LeScript also gives you the printers can be used. It runs on MS-DOS version 2.00 (or ability to "program" these characters so that they can print higher) and requires at least 128K of RAM. LeScript can also out on your printer as unique symbols, designs, small be used as the word processor on the TANDY-1000 DESKMATE pictures, or the actual characters as they appear on the program. Just type COPY LESCRIPT.COM TWTEXT.EXE<ENTER> screen. then run DESKMATE as normal. By taking advantage of the built-in underline and The file format and printer commands of LeScript text boldface capability of the IBM-PC and compatible computers. -

TANDY@ User Guide

TANDY@ Cat. No. 25-3506 1500HD User Guide All portions of this software are copyrighted and are the proprietary and trade secret information of Tandy Corpo- ration and/or its licensor. Use, reproduction, or publica- tion of any portion of this material without the prior written authorization of Tandy Corporation is strictly prohibited. Tandy 1500 HD User's Guide 0 1990 Tandy Corporation. All Rights Reserved. DeskMate, Radio Shack, and Tandy are registered trademarks of Tandy Corporation. GW is a trademark of Microsoft Corporation. IBM is a registered trademark of International Business Machines Corporation. Microsoft and MS-DOS are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. PC is a trademark of International Business Machines Corporation. Tandy 1500 HD BIOS: 0 1984, 1985,1986,1987, 1988 Phoenix Software Associates, Ltd. and Tandy Corporation. All Rights Reserved. DeskMate Spell Checker 0 1986-88 Tandy Corporation; Microlytics, Inc; UFO Systems, Inc; Xerox Corp. All Rights Reserved. GW-BASIC Software: 0 1983, 1984, 1985 Microsoft Corporation. Licensed to Tandy Corporation. All Rights Reserved. MS-DOS Software: 0 1981, 1986 Microsoft Corporation. Licensed to Tandy Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction or use of any portion of this manual, with- out express written permission from Tandy Corporation and/or its licensor, is prohibited. While reasonable efforts have been made in the preparation of this manual to as- sure its accuracy, Tandy Corporation assumes no liability resulting from any errors in or omissions from this man- ual, or from the use of the information contained herein. 10 9 87 65 4 3 2 CONTENTS Before You Begin ........................................................ 5 Package Contents ..................................................... -

Tandy Model I,II,III,4,16100,1000,3000,PC4

At last a computer for those who know NOTHING about computers! • • • and it costs only $800 Later this month, Tandy Electronics is releasing its new TRS-80 computers which were suitable for microcomputer in Australia. Designed especially for use in the their needs were too expensive. At around $20,000 they have been beyond home, small business and school, and by people with no previous most small businesses and self- experience, the TRS-80 is a complete computer system offering employed people, while even the facilities until now found only in systems costing around $15-20,000 schools have only been able to afford a — yet it will be selling for only $799.95. A few weeks ago EA's Editor few, generally purchased by state Jim Rowe was invited by Tandy to review the first sample TRS-80 education departments and "passed around" for a few days at a time system brought to Australia, and here is his report: between individual schools. But the TRS-80 and other small low - When Tandy Electronics invited me professional. cost microcomputer systems now star- to review the advance sample of the In the meantime for a much wider ting to appear on the market are going Australian version of their TRS-80 group of potential users like school to change all \this. For the first time microcomputer system, I was naturally students and teachers, small businesses, since computers were developed in the very interested. Like most microcom- and self-employed people like doctors, late 1940's, almost anyone who needs a puter enthusiasts I had already read solicitors and plumbers the only small computer is going to be able to buy about the TRS-80, which created quite a stir in the USA when it was released there in August last year. -

A History of the GUI 11/3/11 9:20 PM

A History of the GUI 11/3/11 9:20 PM A History of the GUI By Jeremy Reimer | Published 6 years ago Introduction Today, almost everybody in the developed world interacts with personal computers in some form or another. We use them at home and at work, for entertainment, information, and as tools to leverage our knowledge and intelligence. It is pretty much assumed whenever anyone sits down to use a personal computer that it will operate with a graphical user interface. We expect to interact with it primarily using a mouse, launch programs by clicking on icons, and manipulate various windows on the screen using graphical controls. But this was not always the case. Why did computers come to adopt the GUI as their primary mode of interaction, and how did the GUI evolve to be the way it is today? In what follows, I?ll be presenting a brief introduction to the history of the GUI. The topic, as you might expect, is broad, and very deep. This article will touch on the high points, while giving an overview of GUI development. Prehistory Like many developments in the history of computing, some of the ideas for a GUI computer were thought of long before the technology was even available to build such a machine. One of the first people to express these ideas was Vannevar Bush. In the early 1930s he first wrote of a device he called the "Memex," which he envisioned as looking like a desk with two touch screen graphical displays, a keyboard, and a scanner attached to it. -

Tandy 1000 (1984).Pdf

I )OO ._4.! 11 t1J 1I!(.1 The Tandy1000 is you Whatever your applications needs, the new Tandy 1000 is the personal computer for you. That's because the Tandy 1000 has one of the widest selections of software available. Spread- sheet, word processing, integrated applications, home educa- tion, entertainment—it's all available at your local Radio Shack Computer Center. And unlike other personal computers, Tandy 1000 even comes with valuable user software when you buy. We call it DeskMate'M, and it features the applications that today's com- puter users want most. It's your first step in software. and its included with every Tandy 1000. Choose from T] iese Popular MS'-DOS Bush Less Packagest Lotus 123*. The number Quartet Integrated Ac- one seller on every software counting. Includes four in- list! An easy way to go from tegrated accounting spreadsheet to graphics to in- programs to give you the formation management— most up-to-date information instantly! You can change on your company's financial your spreadsheet data di- health. #25-1146, $399.95 rectly and then graph it in DR Graph*. Display com- less than a second. plex data using line, bar, step, #25-1145, $495.00 stick, scatter, pie and charts. Friday! Turn the paper files #25-1151, $195.00 in your office into a more ef- Multiplan. This popular ficient electronic filing sys- "second-generation" spread- Only the Tandy 1000 tem. #25-1149, $299.95 sheet lets you transfer in- Finance Manager. Gain a formation between work- better understanding and sheets automatically. -

A Smorgasbord of Programs Is Available for Your Order

00 O-lwhz O.8.92 In this issue: pfsFILE data file structure revealed, by Roy Soltoff A PRO-WAM Help Displayer, by Matthew Kent Reed LB Data Manager, A Review, by Ken Strickler SYSFLEX: The Flexible /SYS ifie Loader, by Matthew Kent Reed LB Data Manager Version 2.2 released rA 761h M -, .-. pit 7a I 7'/ -- * --. \ A smorgasbord of programs is available for your order Volume Vi.ii $10 Winter 1991/92 PRICE LIST effective February 1, 1992 TRS-80 Software TRS-80 Game Programs Product Nornendature Mod Ill .Mod Price S&H Bouncezoids (M3) M-55-GCB $14.95 AFM: Auto File Manager data base P-50-310 n/a $49.95 D Crazy Painter (M3) M-55-GCP $14.95 BackRest for hard drives P-12-244 P-12-244 $34.95 Frogger (M3) M-55-GCF $14.95 BASIC/S Compiler System P-20-010 n/a $29.95 B Kim Watts Hits (M3) P-55-GKW $9.95 BSORT/ BSORT4 L-32-200 L-32-210 $14.95 Lair of the Dragon (M3/M4) M-55-021 $19.95 CPIM (MM) Hard Disk Drivers H-MM-??? $29.95 B Lance Miklus' Hits (M3) P-55-GLM $19.95 CON8OZ/PRO-CON8OZ. M-30-033 M-31-033 $19.95 Leo Crlstopherson's(M3) P-55-GLC $14.95 diskDlSK/ LS-diskDISK L-35-211 L-35-212 $29.95 Scartman (M3) M-55-GCS $14.95 DISK NOTES from TMQ (per issue) $10.00 Space Castle (M3) M-55-GCC $14.95 DoubleDuty M-02-231 $49.95 The Gobbling Box (M3/M4) M-55-020 $19.95 DSM51 / DSM4 L-35-204 L-35-205 $49.95 DSMBLR / PRO-DUCE M-30-053 M-31-053 $29.95 MSDOS Game Programs EDAS I PRO-CREATE M-20-082 M-21-082 $44.95 D Lair of the Dragon M-86-021 $19.95 EnhComp I PRO-EnhComp M-20-072 M-21-072 $59.95 D Filters: Combined I & II L-32-053 n/a $19.95 B GO:Maintenance -

Tandy® Computer Catalog & Software Reference Guide

1988 Tandy® Computer Catalog & Software Reference Guide Celebrating ten years in the personal computer business. Today, as always, Tandy Computers are the best value for millions of businesses, educators and home users. The new Tandy 4000 unleashes the incredible power of the 80386 microprocessor, for; Radio /haek minicomputer performance in a desktop COMPUTER CENTERS personal computer. A DIVISION OF TANOY CORPORATION TANDY COMPUTERS: Serviced by Radio Shack In today's office, the microcomputer is as in- dispensable as the tele- phone. Radio Shack understands this and of- fers service responsive- ness previously available only on mainframe com- puters, yet at a fraction of the cost. Ten years ago, Radio Shack led the way in personal computing with our breakthrough TRS-80 computer. Nationwide Service. Our 154 company-owned Radio As we enter our second decade in the personal computer Shack Computer Service Centers assure convenient ser- business, Radio Shack is again leading the way, with the vice nationwide. Service is performed by employees of best-selling brand of PC compatibles in America. The the same company that manufactured and sold you your secret to our success is simple: we offer a combination of computer. We we strive to get your system "up and benefits no other company can match. running" as quickly as possible. On-Site and Carry-In Service. In most market areas, Quality. Reliable performance is our design objective. service is available at your place of business, as well as Our engineering team takes pride in the exceptional qual- ours. At our Business Products Service Centers, you can ity they can produce utilizing our proprietary test equip- bring in your computer for routine service performed ment. -

Information Worth Sov Ng11

THE MISOSYS QUARTERLY Information worth sov ng11, In this issue: TI A0 W5 Fast In-Memory Sort Using ALL XLR8er RAM, by Frank Slinkman Using XLR8er RAM as Graphics Video RAM, by Frank Slinkman Upgrade your 4P with external floppy drives, by Tsun Tam CW Doubling of files solved, by Frank Durda, IV ow More Hi-Res graphics game patches, 0 by Ken Strickler WY SuperScripsit document file format, by Tom Price FELSWOOP PRO-WAM Export Utility, by Jeff Joseph LS-DOS 6.3.1 released for the Models 4 and 11/12! NOTE: MISOSYS now publishes DoubleDuty OG 9 Volume IV.iii $10 Spring 90 Books by Christopher Fara \CkO1)E X MOD-4 BY CHRIS for TRS/LS-DOS 6.3, 232 pages MOD-Ill BY CHRIS for LDOS 5.3, 234 pages MOD-Ill BY CHRIS for TRSDOS 1.3, 210 pages $24.95 each, $39.95 any two, $59.95 any three Complete Owner's Manuals for Models 4/4P/4D and Model III, fully updated for all current DOS versions. These beautifully designed books replace obsolete and confusing Tandy and LDOS manuals and addenda. Mod-Ill editions combine both the "Basic Operations" and "Disk System" manuals in one book. Mod-4 edition has chapters on DOS SuperVisor Calls previously not accessible without a separate "technical" manual. No more fumbling between pages: each subject is contained under a logical, bold heading on one page or on pages facing each other when the book is open, with plenty of blank space for notes. Written in plain English, the manuals are better organized, with more and better examples for use of DOS, JCL and BASIC; include chapters with examples on interfacing of DOS and BASIC with assembly language; describe in detail popular ROM, RAM and DOS subroutines; and provide lots of useful extra information never before published in the Model Ill and Model 4 manuals. -

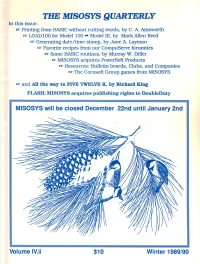

THE MISOSYS QUARTERLY in This Issue: Vw Printing from BASIC Without Cutting Words, by C

THE MISOSYS QUARTERLY In this issue: vw Printing from BASIC without cutting words, by C. A. Ainsworth uw LOAD 100 for Model 100 Model III, by Mark Allen Reed Generating date/time stamp, by Jane A. Layman Favorite recipes from our CompuServe forumites Some BASIC routines, by Murray W. Duller MISOSYS acquires PowerSoft Products Resources: Bulletin boards, Clubs, and Companies re The Cornsoft Group games from MISOSYS ry and All the way to FIVE TWELVE K, by Richard King FLASH: MISOSYS acquires publishing rights to DoubleDuty MISOSYS will be closed December 22nd until January 2nd Volume IV.ii $10 Winter 1989/90 TRSCRO S STM (Pronounced TRJSS-CROSS) TRSCROSS runs on your PC or compatible, yet reads your TRS-80 diskettes! Copy files in either direction! The FASTEST and EASIEST file transfer and conversion program for moving files off the TRS-80 'TMand over to MS-DOS (or PC-DOS) or back TRSCROSS Copyright 1986 by Breeze/QSD, Inc. All rights reserved 1 - Copy from TRS-80 diskette 2 - Copy to TRS-80 diskette 3 - Format TRS-80 diskette 4 - Purge TRS-80 diskette 5 - Display directory (PC or TRS-80) 6 - Exit Shown above is the Main Menu displayed when running TRSCROSS on your PC or compatible. TRSCROSS is as easy to use as it looks to be! The program is TRSCROSS will READ FROM and COPY to the following very straight forward, well thought out, and simple to operate. TRSCROSS has several "help" features built into the program to TRS-80 double-density formats: 5•3*, keep operation as easy as possible. -

Classification of Heterogeneous Operating Systems

Classification of Heterogeneous Operating Systems Kamlesh Sharma* and Dr. T. V. Prasad** * Research Scholar, ** Dean of Academic Affairs Dept. of Comp. Sc. & Engg., Lingaya’s University, Faridabad, India Email: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract — Operating system is a bridge between usable computing system [1]. Moreover, sophisticated system and user. An operating system (OS) is a software operating systems increase the efficiency and consequently program that manages the hardware and software decrease the cost of using a computer [5]. A large number resources of a computer. The OS performs basic tasks, of operating systems of various types are available for both such as controlling and allocating memory, prioritizing research and commercial purposes, and these operating the processing of instructions, controlling input and systems vary greatly in their structures and functionalities output devices, facilitating networking, and managing [1]. files. It is difficult to present a complete as well as deep account of operating systems developed till date. So, this Computers have progressed and developed so have the paper tries to overview only a subset of the available operating systems. Below is a basic list of the different operating systems and its different categories. operating systems and a few examples of operating systems Operating systems are being developed by a large that fall into each of the categories. Many computer number of academic and commercial organizations for operating systems will fall into more than one of the below the last several decades. This paper, therefore, categories.With the integration of computers and concentrates on the different categories of operating telecommunications, the mode of information access systems with special emphasis to those that had deep becomes an important issue. -

A History of the GUI

FOUNDATIONS OF COMPUTING P/T TUTORIAL Reading for weeks 6&7 A History of the GUI By Jeremy Reimer | Published: May 05, 2005 - 01:40AM CT http://arstechnica.com/articles/paedia/gui.ars/1 Introduction Today, almost everybody in the developed world interacts with personal computers in some form or another. We use them at home and at work, for entertainment, information, and as tools to leverage our knowledge and intelligence. It is pretty much assumed whenever anyone sits down to use a personal computer that it will operate with a graphical user interface. We expect to interact with it primarily using a mouse, launch programs by clicking on icons, and manipulate various windows on the screen using graphical controls. But this was not always the case. Why did computers come to adopt the GUI as their primary mode of interaction, and how did the GUI evolve to be the way it is today? In what follows, I’ll be presenting a brief introduction to the history of the GUI. The topic, as you might expect, is broad, and very deep. This article will touch on the high points, while giving an overview of GUI development. Prehistory Like many developments in the history of computing, some of the ideas for a GUI computer were thought of long before the technology was even available to build such a machine. One of the first people to express these ideas was Vannevar Bush. In the early 1930s he first wrote of a device he called the "Memex," which he envisioned as looking like a desk with two touch screen graphical displays, a keyboard, and a scanner attached to it. -

Scott Cutler Department of Computer Science, Rice University Houston, Texas 77005

Scott Cutler Department of Computer Science, Rice University Houston, Texas 77005 Professional Preparation • Ph.D. 6/76, M.S. 6/73, B.S. 6/73 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. • Doctoral minor in Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management. • Ph.D. thesis: "Microcomputer Networks in Control Applications" Rice University Appointments 2001 - Rice University Distinguished Professor of Practice in Computer Technology, Department of Computer Science. • Joint appointment in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering • Research in the areas of smart consumer devices • Teach graduate course COMP 694 / ELEC 694: “How to be a CTO” • Teach COMP 446 / ELEC 446 “Mobile Device Applications” • Computer Sciences Major Advisor (2013 -) • Duncan College Engineering Divisional Advisor (2009 – 2012) • 2011 Outstanding Duncan Faculty Associate • 2012 Office of Academic Advising Faculty Award for Excellence in Advising • Rice Faculty Senate 2012 - 2018 • Rice Faculty Senate Executive Committee 2017-2018 • Created Schedule Planner used by over 3,500 Rice students to plan their course schedule • Active on University committees including parking, mobile presence BUSINESS EXPERIENCE (Prior to joining Rice University) 1998 - 2001 Compaq Computer Corporation VP and Chief Technology Officer, Advanced Technology • Drove Compaq’s wireless technology strategy VP and Chief Technology Officer, Commercial PC Products Group • Conceived and then brought to market the first iPAQ computer. It finished its first year of production at a $1B run rate and was the fastest product to reach 100,000 units. • Chaired Compaq Patent Committee 1995 - 1998 Digital Equipment Corporation (Acquired by Compaq in 1998) VP and Chief Technology Officer, NTSBU (Digital’s PC Business) • Technical lead on strategic activities inside and outside the company.