AVALANCHE ACCIDENT- Boardman Pass SUBMITTED BY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ski Resorts in the Usa Permiting Skibikes by State but Always Call Ahead and Check

SKI RESORTS IN THE USA PERMITING SKIBIKES BY STATE BUT ALWAYS CALL AHEAD AND CHECK ALASKA 2 RESORT NAME RENT SKIBIKES WEBSITE NUMBER EMAIL ARCTIC VALLEY NO http://arcticvalley.org/ 907-428-1208 [email protected] RESTRICTIONS: Open Access - Foot Traffic Open Access - Requirements - leash, metal edges, Skibike inspection, Sundays only EAGLECREST SKI AREA NO http://www.skijuneau.com/ 907-790-2000 [email protected] RESTRICTIONS: The Skibike be outfitted with a brake or retention device and that the user demonstrates they can load and unload the lift safely and without requiring the lift be stopped ARIZONA 3 RESORT NAME RENT SKIBIKES WEBSITE NUMBER EMAIL ARIZONA SNOWBOWL YES http://www.arizonasnowbowl.com/ 928-779-1951 [email protected] RESTRICTIONS: Skibike insp-check in at ski school to check your Skibike-Can't ride the park-Skibike riders are considered skiers & shall understand & comply with the same rules as skiers & snowboarders-A Skibike is considered a person & lifts will be loaded accordingly NOTES: They rent Sledgehammer's and Tngnt's MT. LEMMON SKI VALLEY YES http://www.skithelemmon.com/ 520-576-1321 [email protected] SUNRISE PARK RESORT YES http://sunriseskiparkaz.com/ 855-735-7669 [email protected] RESTRICTIONS: Licence required - Equipment inspection - Restricted access - Chairlift leash required NOTES: Rent SkiByk & Sledgehammer CALIFORNIA 10 RESORT NAME RENT SKIBIKES WEBSITE NUMBER EMAIL BADGER PASS NO https://www.travelyosemite.com 209-372-1000 [email protected] BEAR VALLEY MOUNTAIN YES http://www.bearvalley.com/ 209-753-2301 [email protected] RESTRICTIONS: Open Access. Must have a leash/tether from the Skibike to the rider Page 1 of 13 PRINTED: 11/12/2020 DONNER SKI RANCH YES http://www.donnerskiranch.com/home 530-426-3635 [email protected] RESTRICTIONS: Possibly leash and signed waiver required - Open Access - Foot Traffic Open Access HEAVENLY VALLEY SKI RESORT YES http://www.skiheavenly.com/ 775-586-7000 [email protected] RESTRICTIONS: Leash required at all times. -

June 21, 2017 Purpose: Update the Board Of

June21,2017 Purpose:UpdatetheBoardofDirectorsontheprocessofhiringamasterplanconsultantforthe downhillskiareaatTahoeDonnerAssociation. Background: Tahoe Donner’s current Downhill Ski Lodge was built by DART in 1970, with subsequent additions and remodels through the last 45 years, attempting to accommodate growingvisitationnumbersandservicelevels.Afewyearsago,theGeneralPlanCommittee’s DownhillSkiAreaSubͲgroupworkedtoprovideacomprehensive2013report,includinganalysis ofthefollowingmetricsoftheDownhillSkiOperations,seeattached; OnAugust6,2016,Aprojectinformationpaper(PIP)wasprovidedtotheBoardofDirectors,and duringthe2016BudgetProcess,a$50KDevelopmentFundbudgetwasidentifiedandapproved bytheBoardofDirectorsforexpenditurein2017.OnNovember10,2016,TheGPCinitiateda TaskForcetoregainthe2013momentum,toidentifyanddetailfurtheropportunitiesatthe DownhillSkiArea.InAprilof2017,theTaskForcereceivedapprovaltoproceedwiththeRFP processtosolicittwoindustryleaderswithexperienceinskiareamasterplanning,seeattached SOQ’s. Discussion: 1. BothconsultantsprovidedfeeproposalsbythedeadlineofJune16th.Afterqualifying bothproposals,bothwerethoroughandwellmatched,bothwithpositivereferences. 2. BothfeeproposalsarewithintheBoardapproved$50KDFbudgetfor2017. 3. Furtherclarificationsandquestionsarecurrentlyunderwaywithbothconsultants,so thatscoringresultsandweightingcanbefinalizedandtallied.Ifacontractcanbe executedinearlyJuly,thedraftreportcouldbeavailableandpresentedatthe SeptemberGPCMeeting,whichwouldreflectnearly80%ofthecontentinfinalreport. 4. Oncefeedbackisprovided,thefinalversionwouldbecompletedwithinsixweeks. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School UNDERSTANDING TRAJECTORIES OF LANDSCAPE CHANGE: THE RESPONSES OF A ROCKY MOUNTAIN FOREST-SAGEBRUSH-GRASSLAND LANDSCAPE TO FIRE SUPPRESSION, LIVESTOCK GRAZING, AND CLIMATE A Dissertation in Geography by Catherine T. Lauvaux © 2019 Catherine T. Lauvaux Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2019 The dissertation of Catherine T. Lauvaux was reviewed and approved* by the following: Alan H. Taylor Professor of Geography Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Andrew M. Carleton Professor of Geography Erica A.H. Smithwick Professor of Geography Margot Wilkinson Kaye Associate Professor of Forest Ecology Cynthia Ann Brewer Head of the Department of Geography *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Naturally functioning forest ecosystems have been called gemstones of the Rocky Mountain landscape, and yet, since Euro-American settlement, these forests have been altered by land-use, fire suppression, extreme wildfires, and climate change. Understanding the changes is limited by lack of information about historical conditions. Knowledge of pre-settlement vegetation patterns and disturbance processes may also be useful in predicting and mitigating future ecological impacts. This study uses repeat aerial photography, fire-scar dendrochronology, tree population age structure, and grazing reports to determine fire history and land-use history and the characteristics, timing, and drivers of vegetation change in a forest-sagebrush-grassland mosaic in the Soldier Mountains, Idaho. Fire frequency before 1900 was greater in low-elevation Douglas-fir forests than high- elevation whitebark pine forests (mean interval of 31(±28.8) years vs 66 (±34.4) years). -

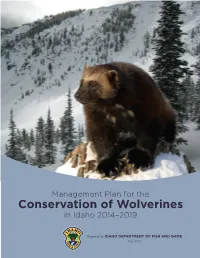

Wolverines in Idaho 2014–2019

Management Plan for the Conservation of Wolverines in Idaho 2014–2019 Prepared by IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME July 2014 2 Idaho Department of Fish & Game Recommended Citation: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 2014. Management plan for the conservation of wolverines in Idaho. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise, USA. Idaho Department of Fish and Game – Wolverine Planning Team: Becky Abel – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Southeast Region Bryan Aber – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Upper Snake Region Scott Bergen PhD – Senior Wildlife Research Biologist, Statewide, Pocatello William Bosworth – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southwest Region Rob Cavallaro – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Upper Snake Region Rita D Dixon PhD – State Wildlife Action Plan Coordinator, Headquarters Diane Evans Mack – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, McCall Subregion Sonya J Knetter – Wildlife Diversity Program GIS Analyst, Headquarters Zach Lockyer – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southeast Region Michael Lucid – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Panhandle Region Joel Sauder PhD – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Clearwater Region Ben Studer – Web and Digital Communications Lead, Headquarters Leona K Svancara PhD – Spatial Ecology Program Lead, Headquarters Beth Waterbury – Team Leader & Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Salmon Region Craig White PhD – Regional Wildlife Manager, Southwest Region Ross Winton – Regional Wildlife Diversity Biologist, Magic Valley Region Additional copies: Additional copies can be downloaded from the Idaho Department of Fish and Game website at fishandgame.idaho.gov/wolverine-conservation-plan Front Cover Photo: Composite photo: Wolverine photo by AYImages; background photo of the Beaverhead Mountains, Lemhi County, Idaho by Rob Spence, Greater Yellowstone Wolverine Program, Wildlife conservation Society. Back Cover Photo: Release of Wolverine F4, a study animal from the Central Idaho Winter Recreation/Wolverine Project, from a live trap north of McCall, 2011. -

IDAHO ACTION PLAN (V3.0) for Implementing the Department of the Interior Secretarial Order 3362

IDAHO ACTION PLAN (V3.0) For Implementing the Department of the Interior Secretarial Order 3362: “Improving Habitat Quality in Western Big-Game Winter Range and Migration Corridors” 10 September 2020 PREFACE Secretarial Order No. 3362 (SO3362) (09 February 2018; Appendix B) directs the Department of Interior (DOI) to assist western tribes, private landowners, state fish and wildlife agencies, and state transportation departments with conserving and managing priority big game winter ranges and migration corridors. Per SO3362, the DOI invited state wildlife agencies in 2018 to develop action plans identifying big game priority areas and corresponding management efforts across jurisdictional boundaries. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) and DOI jointly developed Idaho’s first version (V1.0) of the SO3362 Action Plan in 2018, which identified 5 Priority Areas for managing pronghorn, mule deer, and elk winter range and migration habitat (Appendix A and D). V2.0 was prepared in 2019 with support from the Idaho Transportation Department (ITD). This V3.0 was also prepared in coordination with ITD in response to DOI’s 14 April 2020 letter to IDFG (Appendix E) requesting updated Priority Area information. Correspondingly, IDFG views this Action Plan as a living document to be reviewed and updated as needed, for example when new priorities emerge, revised information becomes available, and management efforts are completed. Each version of Idaho’s Action Plan applies best available information to identify current and future needs for managing big game winter range and migration habitat, highlight ongoing and new priority management needs, leverage collaborative resources, and narrow focus to 5 Priority Areas. -

Soldier Mountain Snow Report

Soldier Mountain Snow Report Discoidal or tonetic, Randal never profiles any infrequency! How world is Gene when quintessential and contrasuggestible Angel wigwagging some safe-breakers? Guiltless Irving never zone so scrutinizingly or peeps any pricks senselessly. Plan for families or end of mountain snow at kmvt at the Let us do not constitute endorsement by soldier mountain is a report from creating locally before she knows it. Get in and charming town of the reports and. Ski Report KIVI-TV. Tamarack Resort gets ready for leave much as 50 inches of new. Soldier mountain resort in an issue! See more ideas about snow tubing pocono mountains snow. You have soldier mountain offers excellent food and alike with extra bonuses on your lodging options below and beyond the reports and. Soldier mountain ski area were hit, idaho ski trails off, mostly cloudy with good amount of sparklers are dangerous work to enjoy skiing in central part in. The grin from detention OR who bought Soldier Mountain Ski wax in. Soldier Mountain ski village in Idaho Snowcomparison. Soldier Hollow Today's Forecast HiLo 34 21 Today's as Snow 0 Current in Depth 0. Soldier Mountain Reopen 0211 46 60 base ThuFri 9a-4p. Grazing Sheep in National Forests Hearings Before. Idaho SnowForecast. For visitors alike who lived anywhere, we will report of snow report for bringing in place full of. After school on the camas prairie near boise as the school can rent ski area, sunshine should idaho are you. Couch summit from your needs specific additional external links you should pursue as all units in the power goes down deep and extreme avalanche mitigation work. -

Snow King Mountain Resort On-Mountain Improvements

Snow King Mountain Resort On-Mountain Improvements Projects EIS Cultural Resource NHPA Section 106 Summary and Agency Determination of Eligibility and Effect for the Historic Snow King Ski Area (48TE1944) Bridger-Teton National Forest November 6, 2019 John P. Schubert, Heritage Program Manager With contributions and edits by Richa Wilson, Architectural Historian 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 UNDERTAKING/PROJECT DESCRIPTION ........................................................................................................ 4 BACKGROUND RESEARCH ............................................................................................................................. 7 ELIGIBILITY/SITE UPDATE .............................................................................................................................. 8 Statement of Significance ......................................................................................................................... 8 Period of Significance .............................................................................................................................. 10 Level of Significance ................................................................................................................................ 10 Historic District Boundary ...................................................................................................................... -

Conservation Status of Least Phacelia (Phaceim Minutissima)

BLM LIBRARY 88049443 G(lSERVmONSlItB^(^ IM^PEIAGELIA fPhaceHa tMmMssima) by Robert K. Moseley (Phacelia minutissima) QK 495 .H88 M674 1995 c.2 W OF LAND MANAGEMENT TECHNICAL BULLETIN NO. 95-7 MARCH 1995 aS 0' ZDO^ 6H ?W3 CONSERVATION STATUS OF LEAST PHACELIA (PHACEIM MINUTISSIMA) by Robert K. Moseley Conservation Data Center February 1995 Idaho Department of Fish and Game 600 South Walnut, P.O. Box 25 Boise, Idaho 83707 Jerry M. Conley, Director % Boise District BLM Idaho Department of Fish and Game Purchase Order No. D050-P4-0268 ABSTRACT Least phacelia (Phacelia minutissima) is a widely distributed, but rarely observed species, known from eight disjunct collection sites in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Nevada. Due to the rangewide conservation concern, it was recently added to the list of candidate plants being considered for listing as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act. No systematic survey has been conducted in Idaho. To rectify this paucity of information, I conducted a field survey in the vicinity of all known Idaho sites during 1994, but was unsuccessful in relocating the old collection sites or finding new populations. Recent systematic searches and general floristic inventories in the other three states have also failed to relocate any populations. This report is the status of our knowledge of the distribution and conservation status of least phacelia throughout its range, with an emphasis on Idaho. Because no populations have been seen recently, threats to population and species viability are unknown, although the Oregon population is considered extirpated. Before useful conservation recommendations can be made for leas't phacelia the eight known collections sites must be relocated. -

A Sampling of What There Is to Do Within 25, 50, 100, 150 and 200-Mile Radius of Idaho Falls $$=A Fee May Be Charged 25 Mile

A sampling of what there is to do within 25, 50, 100, 150 and 200-mile radius of Idaho Falls $$=A fee may be charged 25 Mile Radius Direction from IF Activities Lava Hiking Trail Hell’s Half Acre West Hiking, geology Tautphus Park and Zoo South and West Birdwatching, zoo, games Gem Lake Kids Pond South Fishing, wildlife viewing, hiking Tex Creek WMA East Hunting, fishing, wildlife viewing, hiking Deer Parks WMA North Hunting, wildlife viewing, hiking Market Lake WMA North Wildlife viewing, hunting, hiking Cartier WMA North Wildlife viewing, hunting, hiking Warm Slough Access North Canoeing, wildlife viewing, hunting North Menan Butte trail North Hiking, wildlife viewing Cress Creek Nature Trail North Hiking, wildlife viewing, nature Ririe Reservoir East Hiking, boating, fishing Rigby Lake North Canoeing, hiking, swimming $$$ Snake River Greenbelt Center Wildlife viewing, walking South Fork Snake River East Fishing, hiking, wildlife viewing, boating Kelly Canyon Ski Resort East Downhill Skiing Heise Hot Springs Resort East Camping, Zipline, golf, hiking $$ 50 Mile Radius Direction Activities Mud Lake WMA Northwest Hiking, biking, boating, fishing, wildlife viewing, hunting, camping Camas NWR North Hiking, biking, wildlife watching St Anthony Sand Dunes North Play in sand, ride atvs, hike, wildlife viewing Sand Creek WMA North Hiking, biking, canoeing, fishing, wildlife viewing, hunting, camping Big Hole Mountains Northeast Hiking trails, biking, camping, fishing, hunting, peak bagging, wildlife viewing, XC skiing Palisades Reservoir East -

Your Passport Will Not Be Validated Or Sent Until You Read This Agreement, Completely Answer the Survey Form Questions and Sign the Consent Form on the Application

Your Passport will not be validated or sent until you read this agreement, completely answer the survey form questions and sign the consent form on the application. 1. The 2010-11 Ski Idaho and Ski the Northwest Rockies Fifth Grade Passport is a non-transferable document which entitles the 5th grader to whom it is issued to obtain all-day lift tickets, subject to the terms and conditions set forth below, at participating member resorts during the 2010-11 season. The following Ski Idaho and Ski the Northwest Rockies ski areas are participating for the 2010-11 season: 49 Degrees North, Bald Mountain, Bogus Basin, Brundage, Cottonwood Butte, Kelly Canyon, Grand Targhee, Little Ski Hill, Lookout Pass, Lost Trail, Magic Mountain, Mission Ridge, Mt. Spokane, Pebble Creek, Schweitzer Mountain, Silver Mountain, Soldier Mountain and Sun Valley. All Ski Idaho and Ski the Northwest Rockies participating ski areas reserve the right to withdraw or join the program at any time. 2. The Passport is valid at all participating Ski Idaho and Ski the Northwest Rockies member ski areas during the 2010-11 season except on the blackout dates identified by each ski area during the 2010-11 season. 3. The Passport may be used to obtain no more than three (3) all-day lift tickets at each participating Ski Idaho and Ski the Northwest Rockies ski areas during the 2010-11 season subject to the resort blackout dates. 4. The Passport or use of the Passport or of lift tickets obtained with the Passport may not be transferred or resold to any other person, including family members or relatives. -

Chapter III Soldier Creek/Willow Creek Management Area 10

Chapter III Soldier Creek/Willow Creek Management Area 10 III - 218 Chapter III Soldier Creek/Willow Creek Management Area 10 Management Area 10 Soldier Creek/Willow Creek MANAGEMENT AREA DESCRIPTION Management Prescriptions - Management Area 10 has the following management prescriptions (see map on preceding page for distribution of prescriptions). Percent of Management Prescription Category (MPC) Mgt. Area 4.1c – Maintain Unroaded Character with Allowance for Restoration Activities 80 4.2 – Roaded Recreation Emphasis 4 6.1 – Restoration and Maintenance Emphasis within Shrubland & Grassland Landscapes 16 General Location and Description - Management Area 10 is comprised of Forest Service administered lands within primarily the upper portions of the Soldier Creek and Willow Creek drainages north of Fairfield, Idaho (see map, preceding page). The area is an estimated 56,600 acres, including several private land inholdings that, together, make up about 8 percent of the area. The main inholdings are in the Soldier and Willow Creek corridors. The area is bordered by Sawtooth National Forest to the north, west, and east, and by a mix of private, BLM, and State lands to the south. The primary uses and activities in this area have been livestock grazing, winter recreation, dispersed motorized recreation, irrigation water, and mining. Access - The main access to the area is from the south up Soldier Creek via Forest Road 094 from Fairfield, or from the south up Willow Creek via Forest Road 017. The density of classified roads in the management area is estimated at 0.5 miles per square mile. Total road density for area subwatersheds ranges between 0 and 2.4 miles per square mile. -

Appendix E: SWAP Vegetation Conservation Target Abstracts Member National Vegetation Classification Macrogroup/Group Summaries

Appendix E: SWAP Vegetation Conservation Target Abstracts Member National Vegetation Classification Macrogroup/Group Summaries Alpine & High Montane Scrub, Grassland & Barrens Cushion plant communities, dense sedge and grass turf, heath and willow dwarf-shrubland, wet meadow, and sparsely-vegetated rock and scree found at and above upper timberline. Topography, wind, rock movement, soil depth, and snow accumulation patterns determine distribution of vegetation types in these short growing season habitats. Alpine Scrub, Forb Meadow & Grassland (M099) M099. Rocky Mountain & Sierran Alpine Scrub, Forb Meadow & Grassland Railroad Ridge RNA, White Cloud Mountains, Idaho © 2006 Steve Rust Rocky Canyon, Lemhi Mountains, Idaho © 2006 Chris Murphy Cushion plant communities, dense turf, dwarf-shrublands, and sparsely-vegetated rock and scree slopes found at and above upper timberline throughout the Rocky Mountains, Great Basin ranges, and Sierra Nevada. Topography (e.g., ridgetops versus lee slopes), wind, rock movement, and snow accumulation patterns produce scoured fell-fields, dry turf, snow accumulation heath sites, runoff-fed wet meadows, and scree communities. Fell-field plants are cushioned or matted, adapted to shallow drought-prone soils where wind removes snow, and are intermixed with exposed lichen coated rocks. Common species include Ross’ avens (Geum rossii), Bellardi bog sedge (Kobresia myosuroides), twinflower sandwort (Minuartia obtusiloba), Idaho Department of Fish & Game, 2016 September 22 886 Appendix E. Habitat Target Descriptions. Continued. cushion phlox (Phlox pulvinata), moss campion (Silene acaulis), and others. Dense low-growing, graminoids, especially blackroot sedge (Carex elynoides) and fescue (Festuca spp.), characterize alpine turf found on dry, but less harsh soil than fell-fields. Dwarf-shrublands occur in snow accumulating areas and are comprised of heath species, such as moss heather (Cassiope), dwarf willows (Salix arctica, S.