Вип. 8. ISSN 2518-7694 (Print) ISSN 2518-7708 (Online)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urgently for Publication (Procurement Procedures) Annoucements Of

Bulletin No�4 (183) January 28, 2014 Urgently for publication Annoucements of conducting (procurement procedures) procurement procedures 001143 000833 Luhansk National Agrarian University SOE “Prydniprovska Railway” 91008 Luhansk, Luhansk National Agrarian University 108 Karla Marksa Ave., 49600 Dnipropetrovsk Yevsiukova Liudmyla Semenivna, Bublyk Maryna Borysivna Ivanchak Serhii Volodymyrovych tel.: (095) 532–41–16; tel.: (056) 793–05–28; tel./fax: (0642) 96–77–64; tel./fax: (056) 793–00–41 e–mail: [email protected] Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: www.tender.me.gov.ua www.tender.me.gov.ua Website which contains additional information on procurement: www. tender. uz.gov.ua Website which contains additional information on procurement: www.lnau.lg.ua Procurement subject: code 33.17.1 – repair and maintenance of other Procurement subject: code 06.20.1 – natural gas, liquefied or in a gaseous vehicles and equipment (services in modernization of machine ВПР–02 state (gas exclusively for production of heat energy which is consumed with conducting major repair) – 1 unit by budget institutions and organizations), 1327,0 thousand m3 Supply/execution: on the territory of the winner of the bids; during 10 months from Supply/execution: at the customer’s address; till 31.12.2014 the moment of signing the act of delivery of track machine to modernization with Procurement procedure: procurement from the sole participant repair, but -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

The Cossack Myth: History and Nationhood in the Age of Empires

THE COSSACK MYTH In the years following the Napoleonic Wars, a mysterious manuscript began to circulate among the dissatisfied noble elite of the Russian Empire. Entitled The History of the Rus′, it became one of the most influential historical texts of the modern era. Attributed to an eighteenth-century Orthodox archbishop, it described the heroic struggles of the Ukrainian Cossacks. Alexander Pushkin read the book as a manifestation of Russian national spirit, but Taras Shevchenko interpreted it as a quest for Ukrainian national liberation, and it would inspire thousands of Ukrainians to fight for the freedom of their homeland. Serhii Plokhy tells the fascinating story of the text’s discovery and dissemination, unravelling the mystery of its authorship and tracing its subsequent impact on Russian and Ukrainian historical and literary imagination. In so doing, he brilliantly illuminates the relationship between history, myth, empire, and nationhood, from Napoleonic times to the fall of the Soviet Union. serhii plokhy is the Mykhailo Hrushevsky Professor of Ukrainian History at Harvard University. His previous publications include Ukraine and Russia: Representations of the Past (2008)andThe Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus (2006). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 210.212.129.125 on Sun Dec 23 05:35:34 WET 2012. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139135399 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2012 new studies in european history Edited by PETER -

Lord, History Falls Through the Cracks

kostash/rhubarb 1 LORD, HISTORY FALLS THROUGH THE CRACKS Myrna Kostash 110, 11716 – 100 avenue Edmonton AB T5K 2G3 Tel 780- 433 0710 [email protected] WORD COUNT: 3047 kostash/rhubarb 2 LORD, HISTORY FALLS THROUGH THE CRACKS - Road Map of the Vistula Delta – Dear Heart: Wacek and Hanna bundle me into the back seat of their car and we clatter down the E16 to its junction with the T83, through stolid towns of scrubbed brick and shaved hedges. We are travelling to Gdansk (Danzig). I try to follow your traces, my finger bouncing off the blue lines of the road map as we skirt the edges of potholes. Drewnica, Ostaszewa, Szymankowo, Oslonka. Where are those Frisian farms of yours? We are on our way to Elblag; could that be your Elbing? “Look,” says Wacek, “order and civilization,” indicating the grim slate roofs, the heavy-bottomed Gothic chapels. He is not being ironic. He means: Germans built these towns. Prussians. Not slovenly Poles. Wacek is a Pole. Disposing of vast, waterlogged estates on the Vistula delta, German Catholic and Lutheran landlords in the early 1500s invited Dutch Anabaptists, among them Mennonites, to come dike and dam their lands. The reclamation of wastelands: it was to become a Mennonite speciality. The Prussians had the cities, the pious Anabaptists the reclaimed swamps. By 1608 the bishop of Culm (Chelm?) kostash/rhubarb 3 complained that the whole delta was overrun (his word) by Mennonites. Unmolested at prayer and labour, they had grown prosperous and eventually aroused the envy of their neighbours. This too became a speciality. -

PRESERVING the DNIPRO RIVER Harmony, History and Rehabilitation PRESERVING the DNIPRO RIVER

PRESERVING THE DNIPRO RIVER harmony, history and rehabilitation PRESERVING THE DNIPRO RIVER harmony, history and rehabilitation International Dnipro Fund, Kiev, Ukraine, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, Canada, National Research Institute of Environment and Resources of Ukraine PRESERVING THE DNIPRO RIVER harmony, history and rehabilitation Vasyl Yakovych Shevchuk Georgiy Oleksiyovich Bilyavsky Vasyl M ykolayovych Navrotsky Oleksandr Oleksandrovych Mazurkevich Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Preserving the Dnipro River / V.Y. Schevchuk ... [et al.]. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-88962-827-0 1. Water quality management--Dnieper River. 2. Dnieper River--Environmental conditions. I. Schevchuk, V. Y. QH77.U38P73 2004 333.91'62153'09477 C2004-906230-1 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. Publishing by Mosaic Press, offices and warehouse at 1252 Speers Rd., units 1 & 2, Oakville, On L6L 5N9, Canada and Mosaic Press, PMB 145, 4500 Witmer Industrial Estates, Niagara Falls, NY, 14305-1386, U.S.A. and International Development Research Centre PO Box 8500 Ottawa, ON K1G 3H9/Centre de recherches pour le développement international BP 8500 Ottawa, ON K1G 3H9 (pub@ idrc.ca / www.idrc.ca) -

Udc 911.3.33 the Analysis of the Railway Transport

Section: Section: Geography, demography и astronomy UDC 911.3.33 THE ANALYSIS OF THE RAILWAY TRANSPORT SYSTEM OF THE DNIPROPETROVSK REGION Zavalniuk O.S c.p.s..тeatcher ORCID:0000-0001-6093-732Х Mining and Technological Lyceum Kryvyi Rih ,5000 Odessa National University, Odessa, Dvoryanska, 2, 65029 Sviatetskyi V.Y teacher ORCID 0000-0002-4877-8642 Polytechnic college of State Institution of Higher Education «Kryvyi Rih national university».Krjvji Rig, Karmeljuka,33 50026 Lakomova M.S./ Student National Aviation University, Kiev, Liubomyra Huzara ave. 1, 03058 Abstract. This article reviews and analyzes the indicators of railway transport of Dnipropetrovsk region, namely, freight transportation, freight turnover, passenger transportation, passenger turnover. The analysis was carried out for 2005-2019 by districts and cities of the region, also the place of the region in the transport complex of Ukraine was analyzed. Recommendations for priority areas of development of the railway transport complex of Dnipropetrovsk region have been developed. Key words: railway transport, transport infrastructure, freight transportation and passenger transportation Introduction. Railway transport is one of the most important components of the transport and road complex. It plays a significant role in ensuring the viability of Ukraine's diversified economy. It accounts for 82% of freight turnover (excluding pipeline) and almost 40% of passenger turnover. The most important advantage of railway transport in modern conditions is its efficiency, accessibility and environmental friendliness. This kind of transport, is characterized by the use of electricity for mass transportations, which is a decisive factor in ensuring the competitiveness of rail transport in times of rapidly rising price for petroleum products, and reducing its negative impact on the environment. -

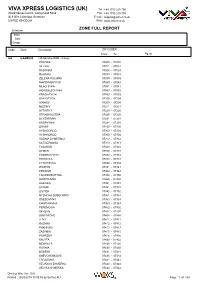

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

The Fluvial Archive of the Middle and Lower Dnieper (A Review)

Netherlands Journal of Geosciences / Geologie en Mijnbouw 81 (3-4): 339-355 (2002) The fluvial archive of the Middle and Lower Dnieper (a review) A.V. Matoshko1, P.F. Gozhik2 & A.S. Ivchenko3 1 Corresponding author, Institute of Geological Sciences, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 55B Gonchara Street, 01054, Kiev. Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected] 2 P.F.Gozhik. Institute of Geological Sciences, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 55B Gonchara Street, 01054, Kiev. Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected] 3 A.S.Ivchenko. Institute of Geography, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, 44, 3 Volodymyrska Street, 01034, Kiev. Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected] r ; Manuscript received: November 2000; accepted: January 2002 Abstract Information about the morphology and alluvial sediments of the Dnieper Valley is reviewed. The Dnieper Valley originated in the Late Miocene. The Middle Dnieper Valley is an intercontinental alluvial basin and the Lower Dnieper Valley is a shallow canyon that ends with a delta. Identification of the alluvial dynamic fades (channel, overbank, abandoned channel) is crucial for stratigraphical analysis. The dynamic fades form regular sequences - alluvial suites that combine into series. Individual suites and series are characterized by their mode of occurrence, fades composition, lithological features and expression in the modern landscape. Their stratigraphic position is established with reference to index beds and palaeontological, geochrono- logical and archaeological research, allowing them to be correlated along the valley. Correlation between different parts of the Dnieper system uses a combination of fades and geomorphological analyses, whereas correlation with other river systems makes use of mammalian and molluscan biostratigraphy. -

39 September 29, 1996

INSIDE:• House-Senate conferees approve earmark for Ukraine — page 3. • Zaporizhia oak is witness to 700 years of history — page 4. • Horbulin’s independence anniversary address — page 8. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIV HE No.KRAINIAN 39 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 29, 1996 EEKLY$1.25/$2 in Ukraine Ukraine’sT independenceU anniversary markedW on Capitol Hill by Yaro Bihun Special to The Ukrainian Weekly WASHINGTON – The fifth anniversary of Ukraine’s independence was marked in the U.S. Congress on September 18 with warm praise for its accomplishments and assurances of support from the U.S. lawmakers who addressed the anniversary luncheon reception in the Senate Russell Office Building. The more than 250 people attending the event also heard a progress report on Ukraine’s development from Volodymyr Horbulin, secretary of the National Security Council of Ukraine, who was the luncheon’s keynote speaker. The reception was sponsored by the Ukrainian American Coordinating Council (UACC), the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA) and Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.) as well some 30 other U.S. senators and representatives. Mr. Horbulin, who was visiting Washington for talks with Clinton administration officials, said Ukraine has laid down a “sound foundation” for a market economy. It has a “clear economic reform strategy,” brought into effect soon after President Leonid Kuchma’s election in 1994, which seeks to achieve and maintain financial sta- bility, control inflation, denationalize and develop a pri- vate sector, and create a favorable climate for foreign investment. The process was helped by the adoption of Ukraine’s new Constitution, which, among other things, ensures var- ious economic and ownership rights, including the right to private property, to own land and the right of entrepre- neurship. -

Translations from Ukrainian Into Serbian Language Between 1991 and 2012 a Study by the Next Page Foundation in the Framework of the Book Platform Project

Translations from Ukrainian into Serbian Language between 1991 and 2012 a study by the Next Page Foundation in the framework of the Book Platform project conducted by Alla Tatarenko1, translated into English by Anna Ivanchenko2 bibliography by Tanya Gaev and Alla Tatarenko February 2013 1 Alla Tatarenko – Ukrainian linguist specializing in Slavic languages, translator, literature historian and literary critic. Professor at the Chair of Slavic Linguistics in Lviv National University named after Ivan Franko. 2 Anna Ivanchenko is translator and interpreter This text is licensed under Creative Commons Translations from Ukrainian into Serbian language Analysis 1. Introduction Ukrainian-Serbian cultural relations have a long-standing tradition, their roots reaching times long gone; however, direct literary contacts have developed in the most active way during the last three centuries. Cultural ties among Serbians, Montenegrians and Ukrainians have evolved in waves, growing stronger and weaker depending on specific historical circumstances.3 The arrival in 1733 of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy teachers to Sremski Karlovtsi to lay down the basis of modern education there served as one of the milestones. During his four years in Voevodina Manuil Kozachynsky did not only work on developing local education but also wrote the first Serbian play, “A Tragicomedy, or a Sad Tale about the Death of Last Serbian Tsar Urosh the Fifth and the Fall of Serbian Kingdom”. That is why Manuil (Mykhaylo) Kozachynsky is considered both a Ukrainian and a Serbian writer, and his personality is usually the first one mentioned when reviewing history of Ukrainian-Serbian cultural relations. Research by M. Golberg, Yu. Guts, I. -

Development of Draft River Basin Management Plan for Dnipro River Basin in Ukraine: Phase 1, Step 1 – Description of the Characteristics of the River Basin

European Union Water Initiative Plus for Eastern Partnership Countries (EUWI+): Results 2 and 3 ENI/2016/372-403 DEVELOPMENT OF DRAFT RIVER BASIN MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR DNIPRO RIVER BASIN IN UKRAINE: PHASE 1, STEP 1 – DESCRIPTION OF THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE RIVER BASIN Report February 2019 Responsible EU member state consortium project leader Ms Josiane Mongellaz, Office International de l’Eau/International Office for Water (FR) EUWI+ country representative in Ukraine Ms Oksana Konovalenko Responsible international thematic lead expert Mr Philippe Seguin, Office International de l’Eau/International Office for Water (FR) Authors Ukrainian Hydrometeorological Institute of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine and National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine Mr Yurii Nabyvanets Ms Nataliia Osadcha Mr Vasyl Hrebin Ms Yevheniia Vasylenko Ms Olha Koshkina Disclaimer: The EU-funded program European Union Water Initiative Plus for Eastern Partnership Countries (EUWI+ 4 EaP) is implemented by the UNECE, OECD, responsible for the implementation of Result 1 and an EU member state consortium of Austria, managed by the lead coordinator Umweltbundesamt, and of France, managed by the International Office for Water, responsible for the implementation of Result 2 and 3. This document “Assessment of the needs and identification of priorities in implementation of the River Basin Management Plans in Ukraine”, was produced by the EU member state consortium with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union or the Governments of the Eastern Partnership Countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of, or sovereignty over, any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries, and to the name of any territory, city or area. -

GEOLEV2 Label Updated October 2020

Updated October 2020 GEOLEV2 Label 32002001 City of Buenos Aires [Department: Argentina] 32006001 La Plata [Department: Argentina] 32006002 General Pueyrredón [Department: Argentina] 32006003 Pilar [Department: Argentina] 32006004 Bahía Blanca [Department: Argentina] 32006005 Escobar [Department: Argentina] 32006006 San Nicolás [Department: Argentina] 32006007 Tandil [Department: Argentina] 32006008 Zárate [Department: Argentina] 32006009 Olavarría [Department: Argentina] 32006010 Pergamino [Department: Argentina] 32006011 Luján [Department: Argentina] 32006012 Campana [Department: Argentina] 32006013 Necochea [Department: Argentina] 32006014 Junín [Department: Argentina] 32006015 Berisso [Department: Argentina] 32006016 General Rodríguez [Department: Argentina] 32006017 Presidente Perón, San Vicente [Department: Argentina] 32006018 General Lavalle, La Costa [Department: Argentina] 32006019 Azul [Department: Argentina] 32006020 Chivilcoy [Department: Argentina] 32006021 Mercedes [Department: Argentina] 32006022 Balcarce, Lobería [Department: Argentina] 32006023 Coronel de Marine L. Rosales [Department: Argentina] 32006024 General Viamonte, Lincoln [Department: Argentina] 32006025 Chascomus, Magdalena, Punta Indio [Department: Argentina] 32006026 Alberti, Roque Pérez, 25 de Mayo [Department: Argentina] 32006027 San Pedro [Department: Argentina] 32006028 Tres Arroyos [Department: Argentina] 32006029 Ensenada [Department: Argentina] 32006030 Bolívar, General Alvear, Tapalqué [Department: Argentina] 32006031 Cañuelas [Department: Argentina]