Teiresias 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Tour of Greece

Grand Tour of Greece Day 1: Monday - Depart USA Depart the USA to Greece. Your flight includes meals, drinks and in-flight entertainment for your journey. Day 2: Tuesday - Arrive in Athens Arrive and transfer to your hotel. Balance of the day at leisure. Day 3: Wednesday - Tour Athens Your morning tour of Athens includes visits to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Panathenian Stadium, the ruins of the Temple of Zeus and the Acropolis. Enjoy the afternoon at leisure in Athens. Day 4: Thursday - Olympia CORINTH Canal (short stop). Drive to EPIDAURUS (visit the archaeological site and the theatre famous for its remarkable acoustics) and then on to NAUPLIA (short stop). Drive to MYCENAE where you visit the archaeological site, then depart for OLYMPIA, through the central Peloponnese area passing the cities of MEGALOPOLIS and TRIPOLIS arrive in OLYMPIA. Dinner & Overnight. Day 5: Friday – Delphi In the morning visit the archaeological site and the museum of OLYMPIA. Drive via PATRAS to RION, cross the channel to ANTIRION on the "state of the art" new suspended bridge considered to be the longest and most modern in Europe. Arrive in NAFPAKTOS, then continue to DELPHI.. Dinner & Overnight. Day 6: Saturday – Delphi In the morning visit the archaeological site and the museum of Delphi. Rest of the day at leisure. Dinner & Overnight in DELPHI. Day 6: Sunday – Kalambaka In the morning, start the drive by the central Greece towns of AMPHISSA, LAMIA and TRIKALA to KALAMBAKA. Afternoon visit of the breathtaking METEORA. Dinner & Overnight in KALAMBAKA. Day 7: Monday - Thessaloniki Drive by TRIKALA and LARISSA to the famous, sacred Macedonian town of DION (visit).Then continue to THESSALONIKI, the largest town in Northern Greece. -

HOMERIC-ILIAD.Pdf

Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power Contents Rhapsody 1 Rhapsody 2 Rhapsody 3 Rhapsody 4 Rhapsody 5 Rhapsody 6 Rhapsody 7 Rhapsody 8 Rhapsody 9 Rhapsody 10 Rhapsody 11 Rhapsody 12 Rhapsody 13 Rhapsody 14 Rhapsody 15 Rhapsody 16 Rhapsody 17 Rhapsody 18 Rhapsody 19 Rhapsody 20 Rhapsody 21 Rhapsody 22 Rhapsody 23 Rhapsody 24 Homeric Iliad Rhapsody 1 Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power [1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles. 8 So, which one of the gods was it who impelled the two to fight with each other in strife [eris]? 9 It was [Apollo] the son of Leto and of Zeus. For he [= Apollo], infuriated at the king [= Agamemnon], [10] caused an evil disease to arise throughout the mass of warriors, and the people were getting destroyed, because the son of Atreus had dishonored Khrysēs his priest. Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Athenians and Eleusinians in the West Pediment of the Parthenon

ATHENIANS AND ELEUSINIANS IN THE WEST PEDIMENT OF THE PARTHENON (PLATE 95) T HE IDENTIFICATION of the figuresin the west pedimentof the Parthenonhas long been problematic.I The evidencereadily enables us to reconstructthe composition of the pedimentand to identify its central figures.The subsidiaryfigures, however, are rath- er more difficult to interpret. I propose that those on the left side of the pediment may be identifiedas membersof the Athenian royal family, associatedwith the goddessAthena, and those on the right as membersof the Eleusinian royal family, associatedwith the god Posei- don. This alignment reflects the strife of the two gods on a heroic level, by referringto the legendary war between Athens and Eleusis. The recognition of the disjunctionbetween Athenians and Eleusinians and of parallelism and contrastbetween individualsand groups of figures on the pedimentpermits the identificationof each figure. The referenceto Eleusis in the pediment,moreover, indicates the importanceof that city and its majorcult, the Eleu- sinian Mysteries, to the Athenians. The referencereflects the developmentand exploitation of Athenian control of the Mysteries during the Archaic and Classical periods. This new proposalfor the identificationof the subsidiaryfigures of the west pedimentthus has critical I This article has its origins in a paper I wrote in a graduateseminar directedby ProfessorJohn Pollini at The Johns Hopkins University in 1979. I returned to this paper to revise and expand its ideas during 1986/1987, when I held the Jacob Hirsch Fellowship at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. In the summer of 1988, I was given a grant by the Committeeon Research of Tulane University to conduct furtherresearch for the article. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

The Herodotos Project (OSU-Ugent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography

Faculty of Literature and Philosophy Julie Boeten The Herodotos Project (OSU-UGent): Studies in Ancient Ethnography Barbarians in Strabo’s ‘Geography’ (Abii-Ionians) With a case-study: the Cappadocians Master thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Linguistics and Literature, Greek and Latin. 2015 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Mark Janse UGent Department of Greek Linguistics Co-Promotores: Prof. Brian Joseph Ohio State University Dr. Christopher Brown Ohio State University ACKNOWLEDGMENT In this acknowledgment I would like to thank everybody who has in some way been a part of this master thesis. First and foremost I want to thank my promotor Prof. Janse for giving me the opportunity to write my thesis in the context of the Herodotos Project, and for giving me suggestions and answering my questions. I am also grateful to Prof. Joseph and Dr. Brown, who have given Anke and me the chance to be a part of the Herodotos Project and who have consented into being our co- promotores. On a whole other level I wish to express my thanks to my parents, without whom I would not have been able to study at all. They have also supported me throughout the writing process and have read parts of the draft. Finally, I would also like to thank Kenneth, for being there for me and for correcting some passages of the thesis. Julie Boeten NEDERLANDSE SAMENVATTING Deze scriptie is geschreven in het kader van het Herodotos Project, een onderneming van de Ohio State University in samenwerking met UGent. De doelstelling van het project is het aanleggen van een databank met alle volkeren die gekend waren in de oudheid. -

The Thermopylae Line

CHAPTER 6 THE THERMOPYLAE LINE ENERAL Wavell arrived in Athens on the 19th April and immediately e Gheld a conference at General Wilson's quarters . Although an effectiv decision to embark the British force from Greece had been made on a higher level in London, the commanders on the spot now once agai n deeply considered the pros and cons . The Greek Government was unstable and had suggested that the British force should depart in order to avoid further devastation of the country. It was unlikely that the Greek Army of Epirus could be extricated and some of its senior officers were urging sur- render. General Wilson considered that his force could hold the Ther- mopylae line indefinitely once the troops were in position.l "The arguments in favour of fighting it out, which [it] is always better to do if possible, " wrote Wilson later,2 "were : the tying up of enemy forces, army and air , which would result therefrom ; the strain the evacuation would place o n the Navy and Merchant Marine ; the effect on the morale of the troops and the loss of equipment which would be incurred . In favour of with- drawal the arguments were : the question as to whether our forces in Greece could be reinforced as this was essential ; the question of the maintenance of our forces, plus the feeding of the civil population ; the weakness of our air forces with few airfields and little prospect of receiving reinforcements ; the little hope of the Greek Army being able to recover its morale . The decision was made to withdraw from Greece ." The British leaders con- sidered that it was unlikely that they would be able to take out any equip- ment except that which the troops carried, and that they would be lucky "to get away with 30 per cent of the force" . -

(Eponymous) Heroes

is is a version of an electronic document, part of the series, Dēmos: Clas- sical Athenian Democracy, a publicationpublication ofof e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org]. e electronic version of this article off ers contextual information intended to make the study of Athenian democracy more accessible to a wide audience. Please visit the site at http:// www.stoa.org/projects/demos/home. Athenian Political Art from the fi h and fourth centuries: Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes S e Cleisthenic reforms of /, which fi rmly established democracy at Ath- ens, imposed a new division of Attica into ten tribes, each of which consti- tuted a new political and military unit, but included citizens from each of the three geographical regions of Attica – the city, the coast, and the inland. En- rollment in a tribe (according to heredity) was a manda- tory prerequisite for citizenship. As usual in ancient Athenian aff airs, politics and reli- gion came hand in hand and, a er due consultation with Apollo’s oracle at Delphi, each new tribe was assigned to a particular hero a er whom the tribe was named; the ten Amy C. Smith, “Athenian Political Art from the Fi h and Fourth Centuries : Images of Tribal (Eponymous) Heroes,” in C. Blackwell, ed., Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy (A.(A. MahoneyMahoney andand R.R. Scaife,Scaife, edd.,edd., e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org], . © , A.C. Smith. tribal heroes are thus known as the eponymous (or name giving) heroes. T : Aristotle indicates that each hero already received worship by the time of the Cleisthenic reforms, although little evi- dence as to the nature of the worship of each hero is now known (Aristot. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

International Journal of Professional Business Review ISSN: 2525-3654 Universidade da Coruña Tzedopoulos, Yorgos; Kamara, Afroditi; Lampada, Despoina; Ferla, Kleopatra THERMALISM IN GREECE: AN OLD CULTURAL HABITUS IN CRISIS International Journal of Professional Business Review, vol. 3, no. 2, 2018, July-December, pp. 205-219 Universidade da Coruña DOI: https://doi.org/10.26668/businessreview/2018.v3i2.83 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=553658822005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Responsible Editor: Maria Dolores Sánchez-Fernández, Ph.D. Associate Editor: Manuel Portugal Ferreira, Ph.D. Evaluation Process: Double Blind Review pelo SEER/OJS THERMALISM IN GREECE: AN OLD CULTURAL HABITUS IN CRISIS TERMALISMO NA GRÉCIA: UM HÁBITO CULTURAL ANTIGO EM CRISE Yorgos Tzedopoulos ¹ ABSTRACT 2 This paper examines thermalism in Greece both in its historical development and in the context of current challenges engendered Afroditi Kamara by economic recession. The authors’ intention is to discuss bathing in thermal springs as a sociocultural practice deeply rooted in 3 history and collective experience (Erfurt-Cooper & Cooper, 2009), to follow its transformations in the course of time, and to Despoina Lampada analyze the complexity of its present state. The latter issue, which is dealt with in more detail, is explored through academic 4 Kleopatra Ferla literature, the evaluation of quantitative and qualitative data, and empirical research. The last part of the paper discusses the conclusions of our study of the Greek case with a view to contributing to the overall assessment of popular thermalism in Europe. -

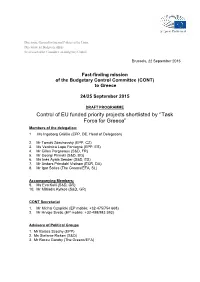

Control of EU Funded Priority Projects Shortlisted by ''Task Force for Greece

Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union Directorate for Budgetary Affairs Secretariat of the Committee on Budgetary Control Brussels, 22 September 2015 Fact-finding mission of the Budgetary Control Committee (CONT) to Greece 24/25 September 2015 DRAFT PROGRAMME Control of EU funded priority projects shortlisted by ‘’Task Force for Greece” Members of the delegation: 1 .Ms Ingeborg Gräßle (EPP, DE, Head of Delegation) 2. Mr Tomáš Zdechovský (EPP, CZ) 3. Ms Verónica Lope Fontagné (EPP, ES) 4. Mr Gilles Pargneaux (S&D, FR) 5. Mr Georgi Pirinski (S&D, BG) 6. Ms Inés Ayala Sender (S&D, ES) 7. Mr Anders Primdahl Vistisen (ECR, DA) 8. Mr Igor Šoltes (The Greens/EFA, SL) Accompanying Members: 9. Ms Eva Kaili (S&D, GR) 10. Mr Miltiadis Kyrkos (S&D, GR) CONT Secretariat 1. Mr Michal Czaplicki (EP mobile: +32-475/754 668) 2. Mr Hrvoje Svetic (EP mobile: +32-498/983 593) Advisors of Political Groups 1. Mr Balazs Szechy (EPP) 2. Ms Stefanie Ricken (S&D) 3. Mr Roccu Garoby (The Greens/EFA) Commission DG REGIO 1. Mr Stylianos Loupasis, - team leader 2. Mr Antonios Sartzetakis (Thessaloniki Metro, double high-speed railway line Tithorea- Lianokladi-Domokos, E65, Karla Lake). 3. Mr Panayiotis Thanou (cadastre, E-ticket, national registry. He is a desk officer (AD) in charge of Digital OP). ECA Mr Lazaros Lazarou, Member of the European Court of Auditors Interpreters FR Ms Stalia Georgoulis - team leader Ms Nathalie Paspaliari EN Ms Ioulia Spetsiou Mr Jose Fisher Rodrigu EL Ms Maria Provata Ms Vasiliki Chrysanthakopo Mr Laurent Recchia - technician, valise Languages covered EN, FR, EL Coordination in Athens - European Parliament Information Office Ms Maria KAROUZOU - logistics Mr Leonidas ANTONAKOPOULOS Head of Information Office of the European Parliament in Greece (8 Leof. -

1 Reading Athenaios' Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition And

Reading Athenaios’ Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition and Commentaries DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corey M. Hackworth Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Fritz Graf, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Carolina López-Ruiz 1 Copyright by Corey M. Hackworth 2015 2 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo that was found at Delphi in 1893, and since attributed to Athenaios. It is believed to have been performed as part of the Athenian Pythaïdes festival in the year 128/7 BCE. After a brief introduction to the hymn, I provide a survey and history of the most important editions of the text. I offer a new critical edition equipped with a detailed apparatus. This is followed by an extended epigraphical commentary which aims to describe the history of, and arguments for and and against, readings of the text as well as proposed supplements and restorations. The guiding principle of this edition is a conservative one—to indicate where there is uncertainty, and to avoid relying on other, similar, texts as a resource for textual restoration. A commentary follows, which traces word usage and history, in an attempt to explore how an audience might have responded to the various choices of vocabulary employed throughout the text. Emphasis is placed on Athenaios’ predilection to utilize new words, as well as words that are non-traditional for Apolline narrative. The commentary considers what role prior word usage (texts) may have played as intertexts, or sources of poetic resonance in the ears of an audience.