DISENTANGLING the RIGHT of PUBLICITY ABRIDGED for COURSE READING (The Tilda ~ Indicates Omitted Material)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disentangling the Right of Publicity

Copyright 2017 by Eric E. Johnson Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 111, No. 4 Articles DISENTANGLING THE RIGHT OF PUBLICITY Eric E. Johnson ABSTRACT—Despite the increasing importance attached to the right of publicity, its doctrinal scope has yet to be clearly articulated. The right of publicity supposedly allows a cause of action for the commercial exploitation of a person’s name, voice, or image. The inconvenient reality, however, is that only a tiny fraction of such instances are truly actionable. This Article tackles the mismatch between the blackletter doctrine and the shape of the case law, and it aims to elucidate, in straightforward terms, what the right of publicity actually is. This Article explains how, in the absence of a clear enunciation of its scope, courts have come to define the right of publicity negatively, through the application of independent defenses based on free speech guarantees and copyright preemption. This inverted doctrinal structure has created a continuing crisis in the right of publicity, leading to unpredictable outcomes and the obstruction of clear thinking about policy concerns. The trick to making sense of the right of publicity, it turns out, is to understand that the right of publicity is not really one unitary cause of action. Instead, as this Article shows, the right of publicity is best understood as three discrete rights: an endorsement right, a merchandizing entitlement, and a right against virtual impressment. This restructuring provides predictability and removes the need to resort to constitutional doctrines and preemption analysis to resolve everyday cases. The multiple- distinct-rights view may also provide pathways to firmer theoretical groundings and more probing criticisms. -

Cape Coral Daily Breeze for an Article Obama Announced to the Crowd on the U.S

Tip off APE ORAL District 5A-15 C C boys basketball tourney begins DAILY BREEZE — SPORTS cape-coral-daily-breeze.com WEATHER: Partly Sunny • Tonight: Partly Cloudy • Thursday: Partly Sunny — 2A Vol. 48, No. 34 Wednesday, February 11, 2009 50 cents Stimulus plan focus of presidential visit By GRAY ROHRER [email protected] An audience of 1,500 people greeted President Barack Obama with a sea of lofted cell phones and cameras Tuesday as he entered the Harborside Event Center in Fort Myers, clamoring President to capture a piece of local history. Barack Obama delivered a 20-minute Obama speech emphasizing the need for a speaks at the more than $800 billion economic town hall stimulus package and how it will affect Southwest Florida resi- meeting he dents, before taking questions held Tuesday from the audience. at the “We cannot afford to wait. I Harborside believe in hope, but I also believe Event Center in action,” Obama told the crowd. in Fort Myers. “We can’t afford to posture More photos and bicker and resort to the same are available failed ideas that got us into this online at: mess in the first place,” he added, cu.cape- prodding recalcitrant Republicans coral-daily- to support the stimulus package. Republican Gov. Charlie Crist breeze.com. embraced the bipartisan spirit advocated by Obama, and MICHAEL stressed how the stimulus could PISTELLA help Florida balance its budget and jump start infrastructure proj- ects. “We need to do this (pass the stimulus package) in a bipartisan way. Helping the country should be about helping the country, not partisan politics,” Crist said before introducing the president. -

2004 January

University Communications Pauline Young, Director News www.moreheadstate.edu Morehead State University UPO Box 1100 Morehead, KY 40351-1689 (606) 783-2030 Jan.6,2004 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MOREHEAD, Ky.---High-tech learning at Morehead State University has received a big boost, thanks to a new grant in the humanities disciplines. Three faculty members in the Department of Communication and Theatre have written a grant that was funded by the SMARTer Kids Foundation, part of SMART Technologies Inc. of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. The primary purpose of the grant, which was matched by the University's Grants Cash Match program, is to purchase SMART Board interactive whiteboards to be used in classrooms in Breckinridge Hall, the Combs Building and the Claypool-Young Art Building. The whiteboard technology is an interactive tool, by which users can substitute their fingers or hands to perform any function typically done by a computer mouse. Files can be opened, moved and altered with direct hand contact, all on a screen-like piece of equipment that measures about six feet across. It roughly combines the features of a computer monitor, a projection screen and a blackboard. The whiteboards are leading-edge educational technology, according to Dr. Cathy Thomas, associate professor of speech and project director of the grant. "We're really excited to get this technology," she said. "This truly makes Breckinridge a state of the art communication building." Dr. Thomas explained that the whiteboards work with common personal computer software, or Macintosh-compatible software, as applicable. "Basically, the computer applications we're. familiar with now will still be available with these boards." Also, she continued, the SMART Board Notebook uses something akin to "a kicked-up version ofPowerPoint." Dr. -

Seeking Full Inclusion CAIR Is America’S Largest Muslim Civil Liberties and Advocacy Organization

Council on American-Islamic Relations The STATUS OF MUSLIM CIVIL RIGHts in the UNITED STATES 2009 Seeking Full Inclusion CAIR is America’s largest Muslim civil liberties and advocacy organization. Its mission is to enhance the understanding of Islam, encourage dialogue, protect civil liberties, empower American Muslims, and build coalitions that promote justice and mutual understanding. CAIR would like to acknowledge and thank Khadija Athman, Nadhira Al-Khalili, Aisha Shaikh, Hafsa Ahmad and Nabila Ahmad for their help in the compilation of CAIR’s 2009 Status of Muslim Civil Rights in the United States report. Table of Contents Questions about this report can be directed to: Introduction .................................................................................................................. 5 Council on American-Islamic Relations Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 7 453 New Jersey Avenue, SE 2008 CAIR Civil Rights Findings ................................................................................. 8 Washington, DC 20003 Tel: (202) 488-8787 Statistical Highlights .................................................................................................... 8 Fax: (202) 488-0833 E-Mail: [email protected] • Anti-Muslim Hate Crimes ................................................................................ 9 • Civil Rights Cases by State ........................................................................... 9 • Civil Rights Cases -

FNEEDED Stroke 9 SA,Sam Adams Scars on 45 SA,Sholem Aleichem Scene 23 SA,Sparky Anderson Sixx:A.M

MEN WOMEN 1. SA Steven Adler=American rock musician=33,099=89 Sunrise Adams=Pornographic actress=37,445=226 Scott Adkins=British actor and martial Sasha Alexander=Actress=198,312=33 artist=16,924=161 Summer Altice=Fashion model and actress=35,458=239 Shahid Afridi=Cricketer=251,431=6 Susie Amy=British, Actress=38,891=220 Sergio Aguero=An Argentine professional Sue Ane+Langdon=Actress=97,053=74 association football player=25,463=108 Shiri Appleby=Actress=89,641=85 Saif Ali=Actor=17,983=153 Samaire Armstrong=American, Actress=33,728=249 Stephen Amell=Canadian, Actor=21,478=122 Sedef Avci=Turkish, Actress=75,051=113 Steven Anthony=Actor=9,368=254 …………… Steve Antin=American, Actor=7,820=292 Sunrise Avenue Shawn Ashmore=Canadian, Actor=20,767=128 Soul Asylum Skylar Astin=American, Actor=23,534=113 Sonata Arctica Steve Austin+Khan=American, Say Anything Wrestling=17,660=154 Sunshine Anderson Sean Avery=Canadian ice hockey Skunk Anansie player=21,937=118 Sammy Adams Saving Abel FNEEDED Stroke 9 SA,Sam Adams Scars On 45 SA,Sholem Aleichem Scene 23 SA,Sparky Anderson Sixx:a.m. SA,Spiro Agnew Sani ,Abacha ,Head of State ,Dictator of Nigeria, 1993-98 SA,Sri Aurobindo Shinzo ,Abe ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Japan, 2006- SA,Steve Allen 07 SA,Steve Austin Sid ,Abel ,Hockey ,Detroit Red Wings, NHL Hall of Famer SA,Stone Cold Steve Austin Spencer ,Abraham ,Politician ,US Secretary of Energy, SA,Susan Anton 2001-05 SA,Susan B. Anthony Sharon ,Acker ,Actor ,Point Blank Sam ,Adams ,Politician ,Mayor of Portland Samuel ,Adams ,Politician ,Brewer led -

Manrlifblrr Hcralji Marcos Resigns, Flees Palace

ZO — MANCHESTER HERALD. Monday, Feb. 24, 1986 U.S./W OBLD FOCUS LOOK FOR THE STARS... ^ E C hockey team i Worst is over dP ^ Crafts business Look for the CLASSIFIED ADS with STARS; stars help you get for California is family affair tourney qualifier better results. Put a star on your ad and see what o ... page 4 ... page 11 ... page 15 ^ difference it makes. Telephone 643-2711, Monday-Friday, * 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m- ^ I APARTMENTS I CONDOMINIUMS I HOMES I HOMES FOR RENT I BUSINESS I HOMES FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE ManrliFBlrr HcralJi FDR SALE HELP WANTED HELP WANTED DPPORTUNITIES ^ Manchester — A City of Village Charm Affordable Housingl Low Manchester — One bed Electricians - Apprentices $167,500. Super Colonial 11 Arvine Place, Manches Individual with collection We haye concession stand All real estate advertised 40's. This spacious one room opartment, stove, experience to assist Col & lourneypersons. Career at local country club 8 plus rooms. Newer 24' x ter — Cuitom designed bedroom condominium refrigerator, references opportunities for expe In the Manchester Herald 24' Fom lly room. 4 bed center chimney Cope lo lection Monooer on port available for leose. Sea Is sublect to the federal will allow the single, required. $290 monthly, time basis. Flexible rienced pre-reolstered, sonal food operation, rooms, 2'A baths, 2 car cated on one of Manches young couple or retired 646-2311. _______________ 25 Cents apprentices & lourneyp Foir Housing Act of 1968, garage. Appliances to re- ter's loveliest treO’llned Tuesday, Feb. 25, 1986 hours, excellent hourly April through October. -

Hunting the Skinwalker

A MAGAZINE DEDICATED TO THOSE WHO LIKE TO THINK DIFFERENTLY IT’S A HOAX! A look at the biggest cases of public deception ISSUE #4 JUL/AUG 2018 HUNTING THE WIN! A SIGNED DVD OF TRAVIS: THE SKINWALKER TRUE STORY Jeremy Corbell and George Knapp OF TRAVIS WALTON discuss their upcoming film about SEE PAGE 36 the infamous Utah ranch MISSING 411 David Paulides investigates mystery disappearances WINGED CRYTPIDS MARIE KAYALI Is it a bird? Is it a plane? Contact, implants and the No, it’s a…? A thunderbird? dark side of the UFO scene JOE FROM THE CAROLINAS Disclosure meets punk rock and rational thinking. POLAND’S UFO INVASION Boomerangs and flying triangles over Eastern Europe. S-4 DIGITAL PRESS Plus more great interviews and features inside! EDITOR’S LETTER WELCOME! “Send in the clowns. Don’t bother, they’re already here.” Stephen Sondheim, A Little Light Music (1973) f there’s one thing we can’t abide talking about The Law of One and it’s liars. Bold-faced liars who will The Synchronicity Key, but over Ido anything for personal gain the last couple of years... So thank while claiming to be something goodness we have people like Joe they’re not. Unfortunately the From The Carolinas bringing logic, alternative community seems reason and common sense back to rife with such characters at the the field of ufology. If you’ve seen moment. We’ve seen various verified his YouTube channel you’ll know documents relating to so-called what he’s about, if you haven’t, whistelblowers, documents which take a few minutes to read our uncover who they truly are. -

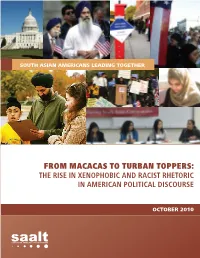

From Macacas to Turban Toppers: the Rise in Xenophobic and Racist Rhetoric in American Political Discourse

SOUTH ASIAN AMERICANS LEADING TOGETHER FROM MACACAS TO TURBAN TOPPERS: THE RISE IN XENOPHOBIC AND RACIST RHETORIC IN AMERICAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE OCTOBER 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 PART I COMMENTS AIMED GENERALLY AT SOUTH ASIAN, MUSLIM, SIKH, AND ARAB AMERICAN COMMUNITIES 4 PART II COMMENTS AIMED AT SOUTH ASIAN CANDIDATES FOR PUBLIC OFFICE 19 PART III TIPS FOR COMMUNITY MEMBERS RESPONDING TO XENOPHOBIC RHETORIC 22 TIMELINE OF KEY POST-SEPTEMBER 11TH DOMESTIC POLICIES AFFECTING 25 SOUTH ASIAN, MUSLIM, SIKH, AND ARAB AMERICAN COMMUNITIES ENDNOTES 28 FROM MACACAS TO TURBAN TOPPERS: THE RISE IN XENOPHOBIC AND RACIST RHETORIC IN AMERICAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY research about such incidents only after that time, primarily Xenophobia and racism have no place in political and civic because of their unprecedented frequency as part of the discourse. Yet, a pattern of such rhetoric continues to exist in broader backlash against these communities. America’s political environment today. For decades, African Divided into three primary sections, the report touches upon Americans and Latinos have been subjected to racist rhetoric the following themes: (1) documented examples of in the political sphere. More recently, as this report shows, xenophobic rhetoric, aimed generally at South Asian, Muslim, South Asians, Muslims, Sikhs, and Arab Americans have been Sikh, or Arab American communities as a whole; the targets of such rhetoric by public officials and political (2) documented examples of such rhetoric aimed specifically candidates from both sides of the aisle. Even more alarming at South Asian candidates running for elected office; and (3) is the use of xenophobia and racism to stir negative responses tips for community members on how to respond to such against political candidates of South Asian descent. -

Insid E the Cove R

Profile of the President - Page 6 Confessions of a Former Neocon - page 3 Affiliate News and Updates - page 4 June/July 2008 The Official Monthly Newspaper of the Libertarian Party Volume 38 / Issue 6. LP Candidate Delegates Nominate Barr to Head ‘08 Ticket Shakes Up By Andrew Davis N.C. Politics he Libertarian Party saw many firsts at its 2008 na- By Andrew Davis Ttional convention, which was held over Memorial Day ichael Munger calls weekend in Denver, CO. Not only himself the “ac- did the Libertarian Party have for Mcountability ham- the first time two former members mer.” In taking his gubernato- of Congress running for the Presi- rial campaign across the state dential nominate, but the Party of North Carolina, he hopes to went through an unprecedented hold major party candidates ac- six rounds of voting to determine countable to the voters by rais- its nominee. In the end, former ing issues he says will “other- Georgia Congressman Bob Barr wise will be ignored.” walked away with the nomination Munger, who was well in-hand and set out to change the known for his golden locks of future of the United States. hair that he grew and donated “I’m sure we will emerge here to the charitable organization with the strongest ticket in the “Locks of Love,” is no politi- history of the Libertarian Party,” Photo courtesy of Terra Eclipse and the Barr 2008 Presidential Campaign (www.BobBarr2008.com) cal amateur. Munger has been Barr stated in his victory speech polling in double digits in some Success in the early polls is behind one of the most successful the chairman of the Duke Uni- shortly after being selected as the states. -

Fantasies of the Aster Race

FANTASIES OF THE ASTER RACE literature, Cinema and the Colonization of American Indians BY WARD CHURCHILL CITY LIGHTS BOOKS SAN FRANCISCO © l 998 by Ward Churchill All Rights Reserved Cover design by Rex Ray Book design by Elaine Katzenberger Typ ography by Harvest Graphics Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Churchill, Ward. Fantasies of the master race : literature, cinema, and the colonization of American Indians I Ward Churchill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Rev. and expanded from the 1992 ed. ISBN 0-87286-348-4 1. Indians in literature. 2. Indians of North America- Public opinion. 3. Public opinion-United States. 4. Racism -United States. 5 Indians in motion pictures. I. Title. PN56.3.I6C49 1998 810.9'35 20397--dc21 98-3624 7 CIP City Lights Books are available to bookstores through our primary distributor: Subterranean Company, P. 0. Box 160, 265 S. 5th St., Monroe, OR 97456. Tel: 541-847-5274. To ll-free orders 800-274-7826. Fax: 541-847-6018. Our books are also available through library jobbers and regional distributors. For personal orders and catalogs, please write to City Lights Books, 261 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94133. Visit our Web site: www. citylights.com CITY LIGHTS BOOKS are edited by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Nancy J. Peters and published at the City Lights Bookstore, 261 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94133. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Those familiar with the original version of Fantasies efthe Master Race will undoubtedly note not only that the line-up of material in the second edition is stronger, but that there has been a marked improvement in quality control. -

Estimating the Impact of Kentucky's Felon Disenfranchisement Policy

Volume 73 Number 1 Home Estimating the Impact of Kentucky’s Felon Disenfranchisement Policy on 2008 Presidential and Senatorial Elections Gennaro F. Vito J. Eagle Shutt Richard Tewksbury Department of Justice Administration, University of Louisville History of Felon Disenfranchisement The Present Study The Survey The Sample Data Collection Procedures Data Analysis Descriptive Statistics of the Sample Estimating Disenfranchised Population Comparing Disenfranchised Voter Preferences to Official Voter Preferences Conclusion FELON DISENFRANCHISEMENT, or the restriction of voting rights for convicted felons, is a staple of American criminal justice policy, practiced in one form or another in 48 of 50 American states. Nevertheless, the practice itself has become increasingly controversial in light of research suggesting disproportionate impacts on minorities and political parties. Disenfranchisement policy currently excludes one in six African- American males. For example, in the 1998 elections, at least 10 states formally disenfranchised 20 percent of African-American voters due to felony convictions (Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 1999). Excluding felons provided “a small but clear advantage to Republican candidates in every presidential and senatorial election from 1972 to 2000” (Manza & Uggen, 2006, p. 191). In addition, felon disenfranchisement may have changed the course of history by costing Al Gore the 2000 presidential election (Uggen & Manza, 2002). Similarly, if not for felon disenfranchisement, Democratic senatorial candidates would likely have prevailed in Texas (1978), Kentucky (1984 and 1992), Florida (1988 and 2004), and Georgia (1992) (Manza & Uggen, 2006, p.194). Since felon disenfranchisement affects the civil rights of nearly five million voters (over 2 percent of the eligible voters), critically evaluating its rationales remains a significant criminal justice policy issue (Manza & Uggen, 2004). -

Theories, Histories, and Politics of Appropriation, Contemporary Art and Culture

EVERYTHING (OLD WAS NEW) ALREADY: THEORIES, HISTORIES, AND POLITICS OF APPROPRIATION, CONTEMPORARY ART AND CULTURE by Riva Susan Symko A thesis submitted to the Department of Art In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (December, 2014) Copyright ©Riva Susan Symko, 2014 Abstract The past decade and a half of technological innovation and explosion of historical multiplicities have reignited the debates on appropriation. This dissertation contributes to the discussion for the purposes of understanding appropriation’s significance to our fluctuating conceptions of authenticity and originality, and to our long-standing cultural institutions (specifically, copyright). Critics of certain kinds of appropriation (like pastiche) have argued it is nothing more than a vague, empty form of mimicry, more closely related to theft than to creative production. On the other hand, advocates for certain kinds of appropriation (like parody, satire, or collage) have regarded it as a useful form of criticism and as a catalyst for inventing new modes of expression in a postmodern moment. Some of the most conspicuous and effecting conversations about appropriation and creative production have lately occurred in relation to intellectual property legislation. Although it is often taken for granted that copyright laws protect creative producers, this dissertation follows recent revelations in literary, and communications studies which have revealed the complex tension between these producers and the economically directed industries that are both driven by, and support those producers. This thesis updates arguments about appropriation for a contemporary context by critically examining these claims from a postcolonial, Marxist perspective considered largely through contemporary Western visual art, film, fashion, and music.