Fantasies of the Aster Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boxoffice Records: Season 1937-1938 (1938)

' zm. v<W SELZNICK INTERNATIONAL JANET DOUGLAS PAULETTE GAYNOR FAIRBANKS, JR. GODDARD in "THE YOUNG IN HEART” with Roland Young ' Billie Burke and introducing Richard Carlson and Minnie Dupree Screen Play by Paul Osborn Adaptation by Charles Bennett Directed by Richard Wallace CAROLE LOMBARD and JAMES STEWART in "MADE FOR EACH OTHER ” Story and Screen Play by Jo Swerling Directed by John Cromwell IN PREPARATION: “GONE WITH THE WIND ” Screen Play by Sidney Howard Director, George Cukor Producer DAVID O. SELZNICK /x/HAT price personality? That question is everlastingly applied in the evaluation of the prime fac- tors in the making of motion pictures. It is applied to the star, the producer, the director, the writer and the other human ingredients that combine in the production of a motion picture. • And for all alike there is a common denominator—the boxoffice. • It has often been stated that each per- sonality is as good as his or her last picture. But it is unfair to make an evaluation on such a basis. The average for a season, based on intakes at the boxoffices throughout the land, is the more reliable measuring stick. • To render a service heretofore lacking, the publishers of BOXOFFICE have surveyed the field of the motion picture theatre and herein present BOXOFFICE RECORDS that tell their own important story. BEN SHLYEN, Publisher MAURICE KANN, Editor Records is published annually by Associated Publica- tions at Ninth and Van Brunt, Kansas City, Mo. PRICE TWO DOLLARS Hollywood Office: 6404 Hollywood Blvd., Ivan Spear, Manager. New York Office: 9 Rockefeller Plaza, J. -

THE ART of DREAMING by Carlos Castaneda

THE ART OF DREAMING By Carlos Castaneda [Version 1.1 - Originally scanned, proofed and released by BELTWAY ] [If you correct any errors, please increment the version number and re-release.] AUTHOR'S NOTE: Over the past twenty years, I have written a series of books about my apprenticeship with a Mexican Yaqui Indian sorcerer, don Juan Matus. I have explained in those books that he taught me sorcery but not as we understand sorcery in the context of our daily world: the use of supernatural powers over others, or the calling of spirits through charms, spells, or rituals to produce supernatural effects. For don Juan, sorcery was the act of embodying some specialized theoretical and practical premises about the nature and role of perception in molding the universe around us. Following don Juan's suggestion, I have refrained from using shamanism, a category proper to anthropology, to classify his knowledge. I have called it all along what he himself called it: sorcery. On examination, however, I realized that calling it sorcery obscures even more the already obscure phenomena he presented to me in his teachings. In anthropological works, shamanism is described as a belief system of some native people of northern Asia-prevailing also among certain native North American Indian tribes-which maintains that an unseen world of ancestral spiritual forces, good and evil, is pervasive around us and that these spiritual forces can be summoned or controlled through the acts of practitioners, who are the intermediaries between the natural and supernatural realms. Don Juan was indeed an intermediary between the natural world of everyday life and an unseen world, which he called not the supernatural but the second attention. -

Carlos Castaneda – a Separate Reality

“A Separate Reality: Further Conversations with don Juan” - ©1971 by Carlos Castaneda Contents • Introduction • Part One: The Preliminaries of 'Seeing' o Chapter 1. o Chapter 2. o Chapter 3. o Chapter 4. o Chapter 5. o Chapter 6. o Chapter 7. • Part Two: The Task of 'Seeing' o Chapter 8. o Chapter 9. o Chapter 10. o Chapter 11. o Chapter 12. o Chapter 13. o Chapter 14. o Chapter 15. o Chapter 16. o Chapter 17. • Epilogue Introduction Ten years ago I had the fortune of meeting a Yaqui Indian from northwestern Mexico. I call him "don Juan." In Spanish, don is an appellative used to denote respect. I made don Juan's acquaintance under the most fortuitous circumstances. I had been sitting with Bill, a friend of mine, in a bus depot in a border town in Arizona. We were very quiet. In the late afternoon, the summer heat seemed unbearable. Suddenly he leaned over and tapped me on the shoulder. "There's the man I told you about," he said in a low voice. He nodded casually toward the entrance. An old man had just walked in. "What did you tell me about him?" I asked. "He's the Indian that knows about peyote. Remember?" I remembered that Bill and I had once driven all day looking for the house of an "eccentric" Mexican Indian who lived in the area. We did not find the man's house and I had the feeling that the Indians whom we had asked for directions had deliberately misled us. Bill had told me that the man was a "yerbero," a person who gathers and sells medicinal herbs, and that he knew a great deal about the hallucinogenic cactus, peyote. -

An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 An Examination of Stylistic Elements in Richard Strauss's Wind Chamber Music Works and Selected Tone Poems Galit Kaunitz Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN EXAMINATION OF STYLISTIC ELEMENTS IN RICHARD STRAUSS’S WIND CHAMBER MUSIC WORKS AND SELECTED TONE POEMS By GALIT KAUNITZ A treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Galit Kaunitz defended this treatise on March 12, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eric Ohlsson Professor Directing Treatise Richard Clary University Representative Jeffrey Keesecker Committee Member Deborah Bish Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This treatise is dedicated to my parents, who have given me unlimited love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my committee members for their patience and guidance throughout this process, and Eric Ohlsson for being my mentor and teacher for the past three years. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi Abstract -

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP on SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 Min)

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP ON SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 min) Directed and written by Samuel Fuller Based on a story by Dwight Taylor Produced by Jules Schermer Original Music by Leigh Harline Cinematography by Joseph MacDonald Richard Widmark...Skip McCoy Jean Peters...Candy Thelma Ritter...Moe Williams Murvyn Vye...Captain Dan Tiger Richard Kiley...Joey Willis Bouchey...Zara Milburn Stone...Detective Winoki Parley Baer...Headquarters Communist in chair SAMUEL FULLER (August 12, 1912, Worcester, Massachusetts— October 30, 1997, Hollywood, California) has 53 writing credits and 32 directing credits. Some of the films and tv episodes he directed were Street of No Return (1989), Les Voleurs de la nuit/Thieves After Dark (1984), White Dog (1982), The Big Red One (1980), "The Iron Horse" (1966-1967), The Naked Kiss True Story of Jesse James (1957), Hilda Crane (1956), The View (1964), Shock Corridor (1963), "The Virginian" (1962), "The from Pompey's Head (1955), Broken Lance (1954), Hell and High Dick Powell Show" (1962), Merrill's Marauders (1962), Water (1954), How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), Pickup on Underworld U.S.A. (1961), The Crimson Kimono (1959), South Street (1953), Titanic (1953), Niagara (1953), What Price Verboten! (1959), Forty Guns (1957), Run of the Arrow (1957), Glory (1952), O. Henry's Full House (1952), Viva Zapata! (1952), China Gate (1957), House of Bamboo (1955), Hell and High Panic in the Streets (1950), Pinky (1949), It Happens Every Water (1954), Pickup on South Street (1953), Park Row (1952), Spring (1949), Down to the Sea in Ships (1949), Yellow Sky Fixed Bayonets! (1951), The Steel Helmet (1951), The Baron of (1948), The Street with No Name (1948), Call Northside 777 Arizona (1950), and I Shot Jesse James (1949). -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

I'kaai Party Where the Two Families Meet "Ft "Copsand CONSULT OUR LISTINGS for LAST MINUTE Tv Coiwuum Mc

14-T- HE CAROLINA TIMES SAT., JULY 28, 1979 ; REFLECTIONS SWORD OF JUSTICE The n 0 - CJ BASEBALL Atlanta Braveava . woundedJackColerelleeonHec- Houston Astros tor to finish the lob of proving that O WILD KINGDOM a corrupt police commissioner w: 7:00 and the mob that 'owns' him were THIEVES LIKE US for of an N FOOTBALL responsible the slaying O 60 Tampa Bay Buccaneers va Wa- honest cop. (Repeat; mina.) A backwoods MOVIE -- fugitive and young, shington Redskins HBO (SUSPENSE) girl fall in love in Mississippi during MASTERPIECE THEATRE 'I. "Capricorn One" Elliott Gould, O Karen Black. A stumbles the Depression, in 'Thieves Like Claudius' 'Reign of Terror' Tiber- reporter Us,' directed by Robert Altman ius' haathe onto the acoop of the century-man'- s palace guard emperor to Mars and Keith Carradine (pic- cut off from the outside first space flight starring totally 15 tured) and Shelley Ouvall, premier-in- g world - at Sejanus' order. So how wasahoaxl(RatedPG)(2hra., on television Aug. 4, on 'The can Antonia possibly warn mins.) CBS 10:30 Saturday Night Movies.' RESURRECTION mins.) O GOSPEL Based on the Edward Anderson GD BLACK REFLECTIONS novel that also inspired the earlier N FOOTBALL SOAP FACTORY 11:00 'They Live By Night,' the movie 8 tells the love of Bowie n LAWRENCE WELK SHOW OOOOnews tragic story CJ HEE HAW Conway Twltty. gd odd couple who has HIGH (Carradine), escaped Dave and Sugar, Grandpa, CI 12 O'CLOCK from a prison work farm, and Ramona and Aliaa Jones. (60 CJ SECOND CITY TV Keechie (Miss Duvall), the mins.) V 11:15 uneducated young innocent he CJ M SEARCH OF OO ABC NEWS meets. -

Twisted Trails of the Wold West by Matthew Baugh © 2006

Twisted Trails of the Wold West By Matthew Baugh © 2006 The Old West was an interesting place, and even more so in the Wold- Newton Universe. Until fairly recently only a few of the heroes and villains who inhabited the early western United States had been confirmed through crossover stories as existing in the WNU. Several comic book miniseries have done a lot to change this, and though there are some problems fitting each into the tapestry of the WNU, it has been worth the effort. Marvel Comics’ miniseries, Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather was a humorous storyline, parodying the Kid’s established image and lampooning westerns in general. It is best known for ‘outing’ the Kid as a homosexual. While that assertion remains an open issue with fans, it isn’t what causes the problems with incorporating the story into the WNU. What is of more concern are the blatant anachronisms and impossibilities the story offers. We can accept it, but only with the caveat that some of the details have been distorted for comic effect. When the Rawhide Kid is established as a character in the Wold-Newton Universe he provides links to a number of other western characters, both from the Marvel Universe and from classic western novels and movies. It draws in the Marvel Comics series’ Blaze of Glory, Apache Skies, and Sunset Riders as wall as DC Comics’ The Kents. As with most Marvel and DC characters there is the problem with bringing in the mammoth superhero continuities of the Marvel and DC universes, though this is not insurmountable. -

Downloaded from by Guest on 26 June 2020

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Crime Fiction and Black Criminality Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8zw7q50m Author Martin, Theodore Publication Date 2018-10-17 DOI 10.1093/alh/ajy037 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Crime Fiction and Black Criminality Theodore Martin* Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/alh/article-abstract/30/4/703/5134081 by guest on 26 June 2020 Nor was I up to being both criminal and detective—though why criminal Ididn’tknow. Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man 1. The Criminal Type A remarkable number of US literature’s most recognizable criminals reside in mid-twentieth-century fiction. Between 1934 and 1958, James M. Cain gave us Frank Chambers and Walter Huff; Patricia Highsmith gave us Charles Bruno and Tom Ripley; Richard Wright gave us Bigger Thomas and Cross Damon; Jim Thompson gave us Lou Ford and Doc McCoy; Dorothy B. Hughes gave us Dix Steele. Many other once-estimable authors of the middle decades of the century—like Horace McCoy, Vera Caspary, Charles Willeford, and Willard Motley—wrote novels centrally concerned with what it felt like to be a criminal. What, it is only natural to wonder, was this midcentury preoccupation with crime all about? Consider what midcentury crime fiction was not about: detec- tives. Although scholars of twentieth-century US literature often use the phrases crime fiction and detective fiction interchangeably, the detective and the criminal were, by midcentury, the anchoring pro- tagonists of two distinct genres. While hardboiled detectives contin- ued to dominate the literary marketplace of pulp magazines and paperback originals in the 1940s and 1950s, they were soon accom- panied on the shelves by a different kind of crime fiction, which was *Theodore Martin is Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of Contemporary Drift: Genre, Historicism, and the Problem of the Present (Columbia UP, 2017). -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

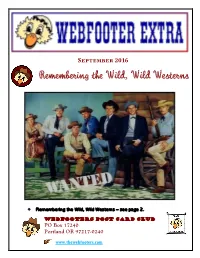

The Webfooter

September 2016 Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns – see page 2. Webfooters Post Card Club PO Box 17240 Portland OR 97217-0240 www.thewebfooters.com Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Before Batman, before Star Trek and space travel to the moon, Westerns ruled prime time television. Warner Brothers stable of Western stars included (l to r) Will Hutchins – Sugarfoot, Peter Brown – Deputy Johnny McKay in Lawman, Jack Kelly – Bart Maverick, Ty Hardin – Bronco, James Garner – Bret Maverick, Wade Preston – Colt .45, and John Russell – Marshal Dan Troupe in Lawman, circa 1958. Westerns became popular in the early years of television, in the era before television signals were broadcast in color. During the years from 1959 to 1961, thirty-two different Westerns aired in prime time. The television stars that we saw every night were larger than life. In addition to the many western movie stars, many of our heroes and role models were the western television actors like John Russell and Peter Brown of Lawman, Clint Walker on Cheyenne, James Garner on Maverick, James Drury as the Virginian, Chuck Connors as the Rifleman and Steve McQueen of Wanted: Dead or Alive, and the list goes on. Western movies that became popular in the 1940s recalled life in the West in the latter half of the 19th century. They added generous doses of humor and musical fun. As western dramas on radio and television developed, some of them incorporated a combination of cowboy and hillbilly shtick in many western movies and later in TV shows like Gunsmoke. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability.