Trade and Empire, 1700-1870

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

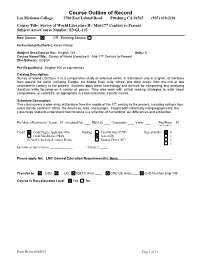

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

Federal Relief Programs in the 19Th Century: a Reassessment

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 19 Issue 3 September Article 8 September 1992 Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment Frank M. Loewenberg Bar-Ilan University, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Social History Commons, Social Work Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Loewenberg, Frank M. (1992) "Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 19 : Iss. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol19/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment FRANK M. LOEWENBERG Bar-Ilan University Israel School of Social Work The American model of the welfare state, incomplete as it may be, was not plucked out of thin air by the architects of the New Deal in the 1930s. Instead it is the product and logical evolution of a long histori- cal process. 19th century federal relief programsfor various population groups, including veterans, native Americans, merchant sailors, eman- cipated slaves, and residents of the District of Columbia, are examined in order to help better understand contemporary welfare developments. Many have argued that the federal government was not in- volved in social welfare matters prior to the 1930s - aside from two or three exceptions, such as the establishment of the Freed- man's Bureau in the years after the Civil War and the passage of various federal immigration laws that attempted to stem the flood of immigrants in the 1880s and 1890s. -

Definingromanticnationalism-Libre(1)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Notes towards a definition of Romantic Nationalism Leerssen, J. Publication date 2013 Document Version Final published version Published in Romantik Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Leerssen, J. (2013). Notes towards a definition of Romantic Nationalism. Romantik, 2(1), 9- 35. http://ojs.statsbiblioteket.dk/index.php/rom/article/view/20191/17807 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 NOTES TOWARDS A DEFINITION Romantic OF ROMANTIC Nationalism NATIONALISM [ JOEP LEERSSEN ABSTR While the concept ‘Romantic nationalism’ is becoming widespread, its current usage tends to compound the vagueness inherent in its two constituent terms, Romanticism and na- tionalism. In order to come to a more focused understanding of the concept, this article A surveys a wide sample of Romantically inflected nationalist activities and practices, and CT nationalistically inflected cultural productions and reflections of Romantic vintage, drawn ] from various media (literature, music, the arts, critical and historical writing) and from dif- ferent countries. -

Georgetown's Historic Houses

VITUAL FIELD TRIPS – GEORGETOWN’S HISTORIC HOUSES Log Cabin This log cabin looks rather small and primitive to us today. But at the time it was built, it was really quite an advance for the gold‐seekers living in the area. The very first prospectors who arrived in the Georgetown region lived in tents. Then they built lean‐tos. Because of the Rocky Mountain's often harsh winters, the miners soon began to build cabins such as this one to protect themselves from the weather. Log cabin in Georgetown Photo: N/A More About This Topic Log cabins were a real advance for the miners. Still, few have survived into the 20th century. This cabin, which is on the banks of Clear Creek, is an exception. This cabin actually has several refinements. These include a second‐story, glass windows, and interior trim. Perhaps these things were the reasons this cabin has survived. It is not known exactly when the cabin was built. But clues suggest it was built before 1870. Historic Georgetown is now restoring the cabin. The Tucker‐Rutherford House James and Albert Tucker were brothers. They ran a grocery and mercantile business in Georgetown. It appears that they built this house in the 1870s or 1880s. Rather than living the house themselves, they rented it to miners and mill workers. Such workers usually moved more often than more well‐to‐do people. They also often rented the places where they lived. When this house was built, it had only two rooms. Another room was added in the 1890s. -

Eugène Delacroix the Artist Eugène Delacroix Born in Saint-Maurice-En-Chalencon, France 1798; Died in Paris, France 1863

Eugène Delacroix Horse Frightened by Lightning , 1824–1829 watercolor, white heightening, gum Arabic watercolor on paper, 94 x 126 in. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, Hungary Self-Portrait, c.1837 oil on canvas The Louvre, Paris The Artist Eugène Delacroix Born in Saint-Maurice-en-Chalencon, France 1798; died in Paris, France 1863 Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix was a French Romantic artist regarded from the outset of his career as the leader of the French Romantic School. Born in France in 1798, Delacroix was orphaned at the age of 16. In 1816 he began his formal art training, learning the neoclassical style of Jacques- Louis David. Delacroix’s first major painting, The Barque of Dante, was accepted into the Paris Salon in 1822, earning him national fame. He turned away from the neoclassical style, and became one of the best-known Romantic painters, favoring imaginative scenes from literature and historical events. Highly acclaimed works include Death of Sardanapalus and Liberty Leading the People , a painting inspired by France’s uprising against King Charles X in 1830. In 1832, Delacroix spent 6 months in North Africa, and created many paintings inspired by Arabic culture and the sun-drenched landscape. Delacroix continued to be very popular in his lifetime, exhibiting many works in the Paris salon, and receiving commissions to decorate important Parisian buildings. Delacroix died on August 13, 1863. Art Movement Romanticism The Romantic Movement was inspired in part by the ideas of Rousseau, who declared that “Man is born free, but is everywhere in chains!” Romanticism emerged from the desire for freedom – political freedom, freedom of thought, of feeling, of action, of worship, of speech, and of taste. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Women's Clothing in the 18Th Century

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions A Peek Inside Mrs. Derby’s Clothes Press: Women’s Clothing in the 18th Century In the parlor of the Derby House is a por- trait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, wearing her finest apparel. But what exactly is she wearing? And what else would she wear? This edition of Pickled Fish focuses on women’s clothing in the years between 1760 and 1780, when the Derby Family were living in the “little brick house” on Derby Street. Like today, women in the 18th century dressed up or down depending on their social status or the work they were doing. Like today, women dressed up or down depending on the situation, and also like today, the shape of most garments was common to upper and lower classes, but differentiated by expense of fabric, quality of workmanship, and how well the garment fit. Number of garments was also determined by a woman’s class and income level; and as we shall see, recent scholarship has caused us to revise the number of garments owned by women of the upper classes in Essex County. Unfortunately, the portrait and two items of clothing are all that remain of Elizabeth’s wardrobe. Few family receipts have survived, and even the de- tailed inventory of Elias Hasket Derby’s estate in 1799 does not include any cloth- ing, male or female. However, because Pastel portrait of Elizabeth Crowninshield Derby, c. 1780, by Benjamin Blythe. She seems to be many other articles (continued on page 8) wearing a loose robe over her gown in imitation of fashionable portraits. -

Empire Under Strain 1770-1775

The Empire Under Strain, Part II by Alan Brinkley This reading is excerpted from Chapter Four of Brinkley’s American History: A Survey (12th ed.). I wrote the footnotes. If you use the questions below to guide your note taking (which is a good idea), please be aware that several of the questions have multiple answers. Study Questions 1. How did changing ideas about the nature of government encourage some Americans to support changing the relationship between Britain and the 13 colonies? 2. Why did Americans insist on “no taxation without representation,” and why did Britain’s leaders find this request laughable? 3. After a quiet period, the Tea Act caused tensions between Americans and Britain to rise again. Why? 4. How did Americans resist the Tea Act, and why was this resistance important? (And there is more to this answer than just the tea party.) 5. What were the “Intolerable” Acts, and why did they backfire on Britain? 6. As colonists began to reject British rule, what political institutions took Britain’s place? What did they do? 7. Why was the First Continental Congress significant to the coming of the American Revolution? The Philosophy of Revolt Although a superficial calm settled on the colonies for approximately three years after the Boston Massacre, the crises of the 1760s had helped arouse enduring ideological challenges to England and had produced powerful instruments for publicizing colonial grievances.1 Gradually a political outlook gained a following in America that would ultimately serve to justify revolt. The ideas that would support the Revolution emerged from many sources. -

On Teaching the History of Nineteenth-Century Music

On Teaching the History of Nineteenth-Century Music Walter Frisch This essay is adapted from the author’s “Reflections on Teaching Nineteenth- Century Music,” in The Norton Guide to Teaching Music History, ed. C. Matthew Balensuela (New York: W. W Norton, 2019). The late author Ursula K. Le Guin once told an interviewer, “Don’t shove me into your pigeonhole, where I don’t fit, because I’m all over. My tentacles are coming out of the pigeonhole in all directions” (Wray 2018). If it could speak, nineteenth-century music might say the same ornery thing. We should listen—and resist forcing its composers, institutions, or works into rigid categories. At the same time, we have a responsibility to bring some order to what might seem an unmanageable segment of music history. For many instructors and students, all bets are off when it comes to the nineteenth century. There is no longer a clear consistency of musical “style.” Traditional generic boundaries get blurred, or sometimes erased. Berlioz calls his Roméo et Juliette a “dramatic symphony”; Chopin writes a Polonaise-Fantaisie. Smaller forms that had been marginal in earlier periods are elevated to unprecedented levels of sophistication by Schubert (lieder), Schumann (character pieces), and Liszt (etudes). Heightened national identity in many regions of the European continent resulted in musical characteristics which become more identifiable than any pan- geographic style in works by composers like Musorgsky or Smetana. At the college level, music of the nineteenth century is taught as part of music history surveys, music appreciation courses, or (more rarely these days) as a stand-alone course. -

Leisure Activities in the Colonial Era

PUBLISHED BY THE PAUL REVERE MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION SPRING 2016 ISSUE NO. 122 Leisure Activities in The Colonial Era BY LINDSAY FORECAST daily tasks. “Girls were typically trained in the domestic arts by their mothers. At an early age they might mimic the house- The amount of time devoted to leisure, whether defined as keeping chores of their mothers and older sisters until they recreation, sport, or play, depends on the time available after were permitted to participate actively.” productive work is completed and the value placed on such pursuits at any given moment in time. There is no doubt that from the late 1600s to the mid-1850s, less time was devoted to pure leisure than today. The reasons for this are many – from the length of each day, the time needed for both routine and complex tasks, and religious beliefs about keeping busy with useful work. There is evidence that men, women, and children did pursue leisure activities when they had the chance, but there was just less time available. Toys and descriptions of children’s games survive as does information about card games, dancing, and festivals. Depending on the social standing of the individual and where they lived, what leisure people had was spent in different ways. Activities ranged from the traditional sewing and cooking, to community wide events like house- and barn-raisings. Men had a few more opportunities for what we might call leisure activities but even these were tied closely to home and business. Men in particular might spend time in taverns, where they could catch up on the latest news and, in the 1760s and 1770s, get involved in politics. -

Reading the Remains of the 17Th Century

AnthroNotes Volume 28 No. 1 Spring 2007 WRITTEN IN BONE READING THE REMAINS OF THE 17TH CENTURY by Kari Bruwelheide and Douglas Owsley ˜ ˜ ˜ [Editor’s Note: The Smithsonian’s Department of Anthro- who came to America, many willingly and others under pology has had a long history of involvement in forensic duress, whose anonymous lives helped shaped the course anthropology by assisting law enforcement agencies in the of our country. retrieval, evaluation, and analysis of human remains for As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the identification purposes. This article describes how settlement of Jamestown, it is clear that historians and ar- Smithsonian physical anthropologists are applying this same chaeologists have made much progress in piecing together forensic analysis to historic cases, in particular seventeenth the literary records and artifactual evidence that remain from century remains found in Maryland and Virginia, which the early colonial period. Over the past two decades, his- will be the focus of an upcoming exhibition, Written in Bone: torical archaeology especially has had tremendous success Forensic Files of the 17th Century, scheduled to open at the in charting the development of early colonial settlements Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in No- through careful excavations that have recovered a wealth vember 2008. This exhibition will cover the basics of hu- of 17th century artifacts, materials once discarded or lost, man anatomy and forensic investigation, extending these and until recently buried beneath the soil (Kelso 2006). Such techniques to the remains of colonists teetering on the edge discoveries are informing us about daily life, activities, trade of survival at Jamestown, Virginia, and to the wealthy and relations here and abroad, architectural and defensive strat- well-established individuals of St. -

The Social Realm of 18Th Century British Ambassadors to France

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses Undergraduate Theses 2015 The Social Realm of 18th Century British Ambassadors to France Andrew M. Bowen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses Recommended Citation Bowen, Andrew M., "The Social Realm of 18th Century British Ambassadors to France" (2015). UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses. 15. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses/15 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 History Thesis The Social Realm of 18th Century British Ambassadors to France By Andrew Bowen Advisor: Paul Deslandes, Professor of History 2 INTRODUCTION This thesis will seek to explain British actions and relations with France both leading up to and during the American and French Revolutions. This time period is critical to understanding the nature of British-French relations for nearly the next century. Existing literature provides some information on political aspects of relations between Britain and France during this period but ignores the important social and familial aspects of ambassadors lives and policies. By fleshing out the influences of individual ambassadors during this period from their social and political relations with their French counterparts we are able to shed light on any possible changes to British policy vis-a-vis France. These social and personal relations could have changed the course of British and French relations over the next century by occurring in this very formative time for both countries.