Amelia Bloomer Amelia Bloomer Was A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Founding Mother The Seneca Falls Convention began a six decade career of women’s rights activism by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. “It has been said that I forged the thunderbolts and she fired them.” Elizabeth Cady Stanton on her partnership with Susan B. Anthony Young Susan B. Anthony Elizabeth Cady sometimes helped in the Stanton and Stanton household. “Susan daughter Harriot, stirs the pudding, Elizabeth 1856. Harriot stirs up Susan, and Susan would also become stirs up the world,” explained a leading advocate Elizabeth’s husband of women’s rights. Henry Stanton. Elizabeth Cady Stanton grew up in a home Project Gutenberg with twelve servants. Early in her marriage Cady Stanton had a more modest lifestyle in A Unique Partnership Seneca Falls, New York. Kenneth C. Zirkel When her children were older Cady Stanton toured eight months She has been called the “outstanding philosopher” of the each year as a paid lecturer. One winter she traveled forty to fifty women’s movement. Even in childhood Elizabeth Cady miles a day by sleigh, often in sub-zero temperatures, when west- Stanton had a passion for equality. In order to compete ern railroads were not running. with boys she studied the “books they read and the games they played,” beginning a lifelong habit of intellectual cu- riosity. Later, as the mother of seven children, she some- times felt like a “caged lioness.” Elizabeth wrote speeches and prepared arguments for her friend Susan B. Anthony Boston to deliver on the lecture circuit. As a young couple Elizabeth Cady Stanton and husband On the Road Henry lived for a time in Massa- chusetts, a center of nineteenth Cady Stanton took to the century reform. -

Darwin and the Women

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS division of the “eight-hour husband” work- ing outside the home and the “fourteen-hour wife” within it. Feminist intellectual Charlotte Perkins Gilman drew on Darwin’s sexual- TTMANN/CORBIS selection theory to argue that women’s eco- BE nomic dependence on men was unnaturally skewing evolution to promote “excessive sex- ual distinctions”. She proposed that economic and reproductive freedom for women would restore female autonomy in choice of mate — which Darwin posited was universal in nature, except in humans — and put human evolutionary progress back on track. L LIB. OF CONGRESS; R: TIME LIFE PICTURES/GETTY; Darwin himself opposed birth control and Women’s advocates (left to right) Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Antoinette Brown Blackwell and Maria Mitchell. asserted the natural inferiority of human females. The adult female, he wrote in The EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY Descent of Man (1871), is the “intermediate between the child and the man”. Neverthe- less, appeals to Darwinist ideas by birth-con- trol advocates such as Margaret Sanger led Darwin and one critic to bemoan in 1917 that “Darwin was the originator of modern feminism”. Feminism in the late nineteenth century was marked by the racial and class politics the women of the era’s reform movements. Blackwell’s and Gilman’s views that women should work outside the home, for example, depended on Sarah S. Richardson relishes a study of how nineteenth- the subjugated labour of lower-class minor- century US feminists used the biologist’s ideas. ity women to perform household tasks. And Sanger’s birth-control politics appealed to contemporary fears of race and class ‘sui- wo misplaced narratives dominate physician Edward cide’. -

Votes for Women! Celebrating New York’S Suffrage on November 6, 1917, New York State Passed the Referendum for Women’S Suffrage

New York State’s Women’s Suffrage History Votes for Women! Celebrating New York’s Suffrage On November 6, 1917, New York State passed the referendum for women’s suffrage. This victory was an important event for New York State and the nation. Suffrage in New York State signaled that the national passage of women’s suffrage would soon follow, and in August 1920, “Votes for Women” were constitutionally guaranteed. Although women began asserting their independence long before, the irst coordinated work for women’s suffrage began at the Seneca Falls convention in 1848. The convention served as a catalyst for debates and action. Women like Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage organized and rallied for support of women’s suffrage throughout upstate New York. Others, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer supported the effort through the use of their pens. Stanton wrote letters, speeches, and articles while Bloomer published the irst newspaper for women, The Lily, in 1849. These combined efforts culminated in the creation of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). By the dawn of the twentieth century, the political and social landscape was much different in New York State than ifty years before. The state experienced dramatic advances in industry and urban growth. Several large waves of immigrants settled throughout the state and now more and more women were working outside of the home. Reformers concerns shifted to labor issues, health care, and temperance. New reformers like Harriot Stanton Blatch and Carrie Chapman Catt used new tactics such as marches, meetings, and signed petitions to show that New Yorkers wanted suffrage. -

Iowa's Role in the Suffrage Movement

Lesson #5 Commemorating the Centennial Of the 19th Amendment Designed for Grades 9-12 6 Lesson Unit/Each Lesson 2 Days Based on Iowa Social Studies Standards Iowa’s Role in the Suffrage Movement Unit Question: What is the 19th Amendment, and how has it influenced the United States? Supporting Question: How was Iowa involved in the promotion of and passage of the 19th Amendment? Lesson Overview The lesson will highlight suffrage leaders with Iowa ties and events in the state leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment. Lesson Objectives and Targets Students will… 1. take note of key events in Iowa’s path to achieve women’s enfranchisement. 2. read provided biographical entries on selected Iowa suffrage leaders. 3. read and review the University of Iowa Library Archives selections on suffrage, selections from the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics website, and the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame coverage about Iowa suffragists and contemporary Iowa women leaders.. Useful Terms and Background ● Iowa Organizations - Iowa Woman Suffrage Association (IWSA), Iowa Equal Suffrage Association (IESA) along with several local and state clubs of support ● National suffrage leaders with Iowa roots - Amelia Jenks Bloomer & Carrie Chapman Catt ● Noted Iowa suffragists included in the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame ● Suffrage activities throughout the state ● Early state attempts for amendments along with Iowa ratification of the 19th Amendment Lesson Procedure Day 1 Teacher Notes for Day 1 1. Point out that lesson materials have been selected from three unique Iowa sources: the University of Iowa Library Archives and the websites for Iowa State University’s Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics and the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame. -

How the Women's Rights Movement Began

How The Women’s Rights Movement Began As it was written in 1787, the Constitution said little about black slaves. It said nothing about women. At the time of the Constitutional Convention, women were treated like children. Adult females were barred from most occupations and professions. They could not make binding contracts or sue people in court. Even though women could be tried for crimes, they were excluded from juries. In most cases, any money or land a woman possessed became the property of her husband once she married. A married woman gave up all individual status; she kept no legal right to her own earnings or even personal belongings such as clothing or jewelry. Most states did not allow single women or widows sole control over their own property, either. Most men simply believed women were not capable of handling business affairs. When the Constitution was written, women could vote only in New Jersey, but by 1807, even this state had banned suffrage (the right of women to vote in governmental elections). The main argument against women voting assumed they would be too easily influenced by their fathers, brothers and husbands. According to this view, if women voted, a married man would control twice the voting power of a single male. From Abolition to Women’s Rights The lack of political clout did not discourage women from becoming deeply involved in public affairs. Lucretia Mott was raised by a MassachusettsLucretia Mott Quaker Wikimedia father Commons) who believed in equal education for girls. She became a teacher and married another Quaker teacher. -

The Women's Suffrage Movement

Name _________________________________________ Date __________________ The Women’s Suffrage Movement Part 1 The Women’s Suffrage Movement began with the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. The idea for the Convention came from two women: Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Both were concerned about women’s issues of the time, specifically the fact that women did not have the right to vote. Stanton felt that this was unfair. She insisted that women needed the power to make laws, in order to secure other rights that were important to women. The Convention was designed around a document that Stanton wrote, called the “Declaration of Sentiments”. Using the Declaration of Independence as her guide, she listed eighteen usurpations, or misuses of power, on the part of men, against women. Stanton also wrote eleven resolutions, or opinions, put forth to be voted on by the attendees of the Convention. About three hundred people came to the Convention, including forty men. All of the resolutions were eventually passed, including the 9th one, which called for women’s suffrage, or the right for women to vote. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott signed the Seneca Falls Declaration and started the Suffrage Movement that would last until 1920, when women were finally granted the right to vote by the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. 1. What event triggered the Women’s Suffrage Movement? ___________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ 2. Who were the two women -

Unit 5- an Age of Reform

Unit 5- An Age of Reform Important People, Terms, and Places (know what it is and its significance) Civil service Gilded Age Primary Recall Initiative Referendum Muckraker Theodore Roosevelt Susan B Anthony Conservation William Howard Taft Jane Addams Woodrow Wilson Carrie Chapman Catt Suffragist Ida Tarbell Frances Willard Upton Sinclair Prohibition Temperance Lucretia Mott Carrie Nation Jacob Riis Booker T Washington W.E.B Dubois Robert LaFollette The Progressive Party 16th Amendment Spoils System Thomas Nast You should be able to write an essay discussing the following: 1. What were political reforms of the period that increased “direct” democracy? 2. The progressive policies of Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson. How did they expand the power of the federal government? 3. The role of the Muckrakers in creating change in America 4. Summarize the other reform movements of the Progressive era. 5. What was the impact of the Progressive Movement on women and blacks? 6. Compare and contrast the beliefs of Booker T. Washington and W.E.B Dubois Important Dates to Remember 1848 – Declaration of Sentiments written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton 1874 – Woman’s Christian Temperance Union formed. 1889 – Jane Addams founds Hull House 1890 – Jacob Riis publishes “How the Other Half Lives” 1895 – Anti Saloon League founded 1904 – Ida Tarbell publishes “The History of Standard Oil” 1906 – Upton Sinclair publishes “The Jungle” 1906 – Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act passed 1909 – National Association for the Advancement of Colored People founded. (NAACP) 1913 – 16th Amendment passed 1914 – Clayton Anti-Trust Act passed 1919 – 18th Amendment passed (prohibition) 1920 – 19th Amendment passed (women’s suffrage) . -

Elizabeth Cady Stanton “Paved the Path for the Passage of the 19Th Amendment” November 12, 1815—October 26, 1902

Elizabeth Cady Stanton “Paved the Path for the Passage of the 19th Amendment” November 12, 1815—October 26, 1902 Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born in Johnstown, New York on November 12, 1815 to one of the city’s most promi- nent and respected couples. As a child, her father showed clear preference for his son over Stanton, so from a young age she showed the determination to excel in typically “male” fields of the time. In 1832, Stanton graduated from Emma Willard’s Troy Female Seminary, then becoming an active member of the abolitionist, temperance, and women’s rights movements through her cousin, reformer Gerrit Smith. In 1840, Stanton married another reformer, Henry Stanton, and they immediately travelled to the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where she and several other women objected their exclusion from the conference. After their time in London, the Stantons returned to Seneca Falls, New York. In July 1848, Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and several other women convened the Seneca Falls Convention. Together, those in attendance wrote the “Declaration of Sentiments” and spearheaded the movement to propose women be granted suffrage. Stanton continued to be a prolific writer and lecturer on women’s rights and other reform topics, and after meeting Susan B. Anthony in the early 1850s, she became one of the national leaders promoting women’s rights, especially the right to vote. During the Civil War, Stanton focused on abolition work, but after the end of the war, she became even more ardent in her work supporting women’s suffrage, working with Susan B. -

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Biography (1815–1902) Elizabeth Cady

Elizabeth Cady Stanton Biography (1815–1902) Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an early leader of the woman's rights movement, writing the Declaration of Sentiments as a call to arms for female equality. Who Was Elizabeth Cady Stanton? Elizabeth Cady Stanton was an abolitionist and leading figure of the early woman's movement. An eloquent writer, her Declaration of Sentiments was a revolutionary call for women's rights across a variety of spectrums. Stanton was the president of the National Woman Suffrage Association for 20 years and worked closely with Susan B. Anthony. Early Life Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born on November 12, 1815, in Johnstown, New York. The daughter of a lawyer who made no secret of his preference for another son, she early showed her desire to excel in intellectual and other "male" spheres. She graduated from Emma Willard's Troy Female Seminary in 1832, and then was drawn to the abolitionist, temperance and women's rights movements through visits to the home of her cousin, the reformer Gerrit Smith. In 1840, Elizabeth Cady Stanton married a reformer Henry Stanton (omitting “obey” from the marriage oath), and they went at once to the World's Anti-Slavery Convention in London, where she joined other women in objecting to their exclusion from the assembly. On returning to the United States, Stanton and Henry had seven children while he studied and practiced law, and eventually, they settled in Seneca Falls, New York. Women's Rights Movement With Lucretia Mott and several other women, Stanton held the famous Seneca Falls Convention in July 1848. -

Woman Suffrage

LOCAL HISTORY & GENEALOGY 115 South Avenue, Rochester, NY 14604 ● 585-428-8370 ● Fax 585-428-8353 Women’s Suffrage Research Guide SCOPE This guide is intended to assist patrons in researching information available at the Rochester Public Library about the women’s suffrage movement. A good place to start your research is by searching the Ready Reference card file by appropriate subject heading. For clarification of any entry, please ask at the reference desk. For a more comprehensive review of the library’s holdings on the women’s suffrage movement, please check with other divisions. INTRODUCTION In the United States of America, the first large-scale organized effort to enfranchise women took place at the Seneca Falls Convention, which was convened by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott in 1848. The Civil War interrupted the momentum of the movement; however, upon its end, agitation by women for the ballot became increasingly determined. A few years after the war, a split developed among feminists over the proposed 15th Amendment, which gave the vote to black men. Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others refused to endorse the amendment because it did not give women the ballot. Other suffragists, including Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe, argued that passage of the amendment could be a stepping stone towards the vote for women. As a result, two distinct organizations emerged. Stanton and Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association to work for suffrage on the federal level and to press for more extensive institutional changes, such as the granting of property rights to married women. -

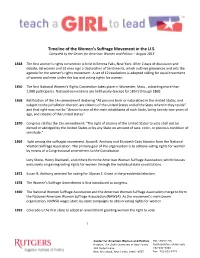

Timeline of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the U.S

Timeline of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S. Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics – August 2014 1848 The first women's rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, New York. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women's rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women. 1850 The first National Women's Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, Mass., attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860. 1868 Ratification of the 14th amendment declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside” and that right may not be “denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States” 1870 Congress ratifies the 15th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” 1869 Split among the suffragist movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution. -

Using Political Cartoons to Explore the Women's Suffrage Movement

Humor and Activism: Using Political Cartoons to Explore the Women’s Suffrage Movement ac·tiv·ism the policy or action of using vigorous campaigning to bring about political or social change. suf·frage the right to vote in an election universal suffrage [=the right of all adult citizens to vote in an election] Purpose: To use political cartoons as a device to analyze and discuss the women’s suffrage movement Lesson Objectives: • Students will define “activism” and relate it to the women’s suffrage movement • Students will analyze how and why opposition to women’s suffrage was revealed through the use of historical political cartoons. • Students will explore how humor and satire can be used to express a point of view and discuss how effective the technique is as a persuasive argument. • Students will present a contemporary political cartoon and analyze the point of view of the artist; is it a statement of support or opposition and why. Time Frame: One to two class sessions Standards: C3: D1.5.9-12. Determine the kinds of sources that will be helpful in answering compelling and supporting questions, taking into consideration multiple points of view represented in the sources, the types of sources available, and the potential uses of the sourcesc3 C3 D2.Civ.2.6-8. Explain specific roles played by citizens (such as voters, jurors, taxpayers, members of the armed forces, petitioners, protesters, and office-holders). C3 D2.Civ.2.9-12. Analyze the role of citizens in the U.S. political system, with attention to various theories of democracy, changes in Americans’ participation over time, and alternative models from other countries, past and present C3 D2.Civ.14.6-8.