On the Creation of a Standard Photometric System for Ultraviolet Astronomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pushing the Limits of the Coronagraphic Occulters on Hubble Space Telescope/Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph

Pushing the limits of the coronagraphic occulters on Hubble Space Telescope/Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph John H. Debes Bin Ren Glenn Schneider John H. Debes, Bin Ren, Glenn Schneider, “Pushing the limits of the coronagraphic occulters on Hubble Space Telescope/Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph,” J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 5(3), 035003 (2019), doi: 10.1117/1.JATIS.5.3.035003. Downloaded From: https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/journals/Journal-of-Astronomical-Telescopes,-Instruments,-and-Systems on 02 Jul 2019 Terms of Use: https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/terms-of-use Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments, and Systems 5(3), 035003 (Jul–Sep 2019) Pushing the limits of the coronagraphic occulters on Hubble Space Telescope/Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph John H. Debes,a,* Bin Ren,b,c and Glenn Schneiderd aSpace Telescope Science Institute, AURA for ESA, Baltimore, Maryland, United States bJohns Hopkins University, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Baltimore, Maryland, United States cJohns Hopkins University, Department of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, Baltimore, Maryland, United States dUniversity of Arizona, Steward Observatory and the Department of Astronomy, Tucson Arizona, United States Abstract. The Hubble Space Telescope (HST)/Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) contains the only currently operating coronagraph in space that is not trained on the Sun. In an era of extreme-adaptive- optics-fed coronagraphs, and with the possibility of future space-based coronagraphs, we re-evaluate the con- trast performance of the STIS CCD camera. The 50CORON aperture consists of a series of occulting wedges and bars, including the recently commissioned BAR5 occulter. We discuss the latest procedures in obtaining high-contrast imaging of circumstellar disks and faint point sources with STIS. -

The Status and Future of EUV Astronomy

The status and future of EUV astronomy M. A. Barstow∗, S. L. Casewell Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK J. B. Holberg Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, 1541 East University Boulevard, Sonett Space Sciences Building, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA M.P. Kowalski Naval Research Laboratory,4555 Overlook Ave SW Washington, DC 20375, USA Abstract The Extreme Ultraviolet wavelength range was one of the final windows to be opened up to astronomy. Nevertheless, it provides very important diagnostic tools for a range of astronomical objects, although the opacity of the interstellar medium restricts the majority of observations to sources in our own galaxy. This review gives a historical overview of EUV astronomy, describes current instrumental capabilities and examines the prospects for future facilities on small and medium-class satellite platforms. Keywords: Extreme Ultraviolet, Spectroscopy, White Dwarfs, Stellar Coronae, Interstellar Medium 1. Introduction arXiv:1309.2181v1 [astro-ph.SR] 9 Sep 2013 The Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) nominally spans the wavelength range from 100 to 912 A,˚ although for practical purposes the edges are often some- what indistinct as instrument band-passes may extend short-ward into the soft X-ray or long-ward into the far ultraviolet (far-UV). The production of EUV photons is primarily associated with the existence of hot, 105-107 K gas ∗Corresponding Author: [email protected] Preprint submitted to Advances in Space Research October 29, 2018 in the Universe. Sources of EUV radiation can be divided into two main cat- egories, those where the emission arises from recombination of ions and elec- trons in a hot, optically thin plasma, giving rise to emission line spectra, and objects which are seen by thermal emission from an optically thick medium, resulting in a strong continuum spectrum which may contain features arising from transitions between different energy levels or ionisation stages of sev- eral elements. -

Precollimator for X-Ray Telescope (Stray-Light Baffle) Mindrum Precision, Inc Kurt Ponsor Mirror Tech/SBIR Workshop Wednesday, Nov 2017

Mindrum.com Precollimator for X-Ray Telescope (stray-light baffle) Mindrum Precision, Inc Kurt Ponsor Mirror Tech/SBIR Workshop Wednesday, Nov 2017 1 Overview Mindrum.com Precollimator •Past •Present •Future 2 Past Mindrum.com • Space X-Ray Telescopes (XRT) • Basic Structure • Effectiveness • Past Construction 3 Space X-Ray Telescopes Mindrum.com • XMM-Newton 1999 • Chandra 1999 • HETE-2 2000-07 • INTEGRAL 2002 4 ESA/NASA Space X-Ray Telescopes Mindrum.com • Swift 2004 • Suzaku 2005-2015 • AGILE 2007 • NuSTAR 2012 5 NASA/JPL/ASI/JAXA Space X-Ray Telescopes Mindrum.com • Astrosat 2015 • Hitomi (ASTRO-H) 2016-2016 • NICER (ISS) 2017 • HXMT/Insight 慧眼 2017 6 NASA/JPL/CNSA Space X-Ray Telescopes Mindrum.com NASA/JPL-Caltech Harrison, F.A. et al. (2013; ApJ, 770, 103) 7 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/770/2/103 Basic Structure XRT Mindrum.com Grazing Incidence 8 NASA/JPL-Caltech Basic Structure: NuSTAR Mirrors Mindrum.com 9 NASA/JPL-Caltech Basic Structure XRT Mindrum.com • XMM Newton XRT 10 ESA Basic Structure XRT Mindrum.com • XMM-Newton mirrors D. de Chambure, XMM Project (ESTEC)/ESA 11 Basic Structure XRT Mindrum.com • Thermal Precollimator on ROSAT 12 http://www.xray.mpe.mpg.de/ Basic Structure XRT Mindrum.com • AGILE Precollimator 13 http://agile.asdc.asi.it Basic Structure Mindrum.com • Spektr-RG 2018 14 MPE Basic Structure: Stray X-Rays Mindrum.com 15 NASA/JPL-Caltech Basic Structure: Grazing Mindrum.com 16 NASA X-Ray Effectiveness: Straylight Mindrum.com • Correct Reflection • Secondary Only • Backside Reflection • Primary Only 17 X-Ray Effectiveness Mindrum.com • The Crab Nebula by: ROSAT (1990) Chandra 18 S. -

Detection of Large-Scale X-Ray Bubbles in the Milky Way Halo

Detection of large-scale X-ray bubbles in the Milky Way halo P. Predehl1†, R. A. Sunyaev2,3†, W. Becker1,4, H. Brunner1, R. Burenin2, A. Bykov5, A. Cherepashchuk6, N. Chugai7, E. Churazov2,3†, V. Doroshenko8, N. Eismont2, M. Freyberg1, M. Gilfanov2,3†, F. Haberl1, I. Khabibullin2,3, R. Krivonos2, C. Maitra1, P. Medvedev2, A. Merloni1†, K. Nandra1†, V. Nazarov2, M. Pavlinsky2, G. Ponti1,9, J. S. Sanders1, M. Sasaki10, S. Sazonov2, A. W. Strong1 & J. Wilms10 1Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Garching, Germany. 2Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia. 3Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, Garching, Germany. 4Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Bonn, Germany. 5Ioffe Institute, St Petersburg, Russia. 6M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, P. K. Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Moscow, Russia. 7Institute of Astronomy, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia. 8Institut für Astronomie und Astrophysik, Tübingen, Germany. 9INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera, Merate, Italy. 10Dr. Karl-Remeis-Sternwarte Bamberg and ECAP, Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Bamberg, Germany. †e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] The halo of the Milky Way provides a laboratory to study the properties of the shocked hot gas that is predicted by models of galaxy formation. There is observational evidence of energy injection into the halo from past activity in the nucleus of the Milky Way1–4; however, the origin of this energy (star formation or supermassive-black-hole activity) is uncertain, and the causal connection between nuclear structures and large-scale features has not been established unequivocally. -

The Spitzer Space Telescope First-Look Survey. II. KPNO

The Spitzer Space Telescope First-Look Survey: KPNO MOSAIC-1 R-band Images and Source Catalogs Dario Fadda1, Buell T. Jannuzi2, Alyson Ford2, Lisa J. Storrie-Lombardi1 [January, 2004 { Submitted to AJ] ABSTRACT We present R-band images covering more than 11 square degrees of sky that were obtained in preparation for the Spitzer Space Telescope First Look Survey (FLS). The FLS was designed to characterize the mid-infrared sky at depths 2 orders of magnitude deeper than previous surveys. The extragalactic component is the ¯rst cosmological survey done with Spitzer. Source catalogs extracted from the R-band images are also presented. The R-band images were obtained using the MOSAIC-1 camera on the Mayall 4m telescope of the Kitt Peak National Observatory. Two relatively large regions of the sky were observed to modest depth: the main FLS extra galac- tic ¯eld (17h18m00s +59o3000000:0 J2000; l= 88:3, b= +34:9) and ELAIS-N1 ¯eld (16h10m01s +54o3003600:0 J2000; l= 84:2, b= +44:9). While both of these ¯elds were in early plans for the FLS, only a single deep pointing test observation were made at the ELAIS-N1 location. The larger Legacy program SWIRE (Lonsdale et al., 2003) will include this region among its sur- veyed areas. The data products of our KPNO imaging (images and object catalogs) are made available to the community through the World Wide Web (via the Spitzer Science Center and NOAO Science Archives). The overall quality of the images is high. The measured positions of sources detected in the images have RMS uncertainties in their absolute positions of order 0.35 arc-seconds with possible systematic o®sets of order 0.1 arc-seconds, depending on the reference frame of comparison. -

Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 97:165-174, Febmary 1985

Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 97:165-174, Febmary 1985 PHOTOMETRY OF STARS IN THE uvgr SYSTEM* STEPHEN M. KENT Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Received 1984 July 23, revised 1984 November 17 Photoelectric photometry is presented for over 400 stars using the uvgr system of Thuan and Gunn. Stars were selected to cover a wide range of spectral type, luminosity class, and metallicity. A mean main sequence is derived along with red- dening curves and approximate transformations to the UBVR system. The calibration of the standard-star sequence is sig- nificantly improved. Key words: photometry—stellar classification I. Introduction II. Observations The uvgr system (Thuan and Gunn 1976, hereafter The observations were made during several runs from TG) was developed as a four-color intermediate-to-wide- 1976 through 1978 on the Palomar 60-inch (1.5-m) tele- band photometric system which was designed to avoid a scope. The instrumentation and equipment were identi- number of pitfalls of the standard UBV system. The four cal with that used by TG. A two-channel pulse-counting bands are nonoverlapping and exclude the strongest S20 photometer allowed for the simultaneous measure- night-sky lines. The u and ν filters lie in a region of ment of object and sky. Each star was observed in both strong line blanketing in late-type stars and measure the apertures except for the globular-cluster stars, where it Balmer jump in early-type stars; the g and r filters lie in was necessary to go off the cluster to measure sky. -

Cosmic Origins Newsletter, September 2016, Vol. 5, No. 2

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Cosmic Origins Newsletter September 2016 Volume 5 Number 2 Summer 2016 Cosmic Origins Program Inside this Issue Update Summer 2016 Cosmic Origins Program Update ............................1 Mansoor Ahmed, COR Program Manager Hubble Reveals Stellar Fireworks in ‘Skyrocket’ Galaxy ................2 Message from the Astrophysics Division Director .........................2 Susan Neff, COR Program Chief Scientist Light Echoes Give Clues to Protoplanetary Disk ............................3 Far-IR Surveyor Study Status .............................................................5 Welcome to the September 2016 Cosmic Origins (COR) newslet- LUVOIR Study Status .........................................................................5 ter. In this issue, we provide updates on several activities relevant to Strategic Astrophysics Technology (SAT) Selections the COR Program objectives. Some of these activities are not under for ROSES-2015 ...................................................................................6 the direct purview of the program, but are relevant to COR goals, Technology Solicitations to Enable Astrophysics Discoveries ......6 therefore we try to keep you informed about their progress. Cosmic Origins Suborbital Program: Balloon Program – BETTII ................................................................7 In January 2016, Paul Hertz (Director, NASA Astrophysics) News from SOFIA ...............................................................................8 presented his -

Observations of Comet IRAS-Araki-Alcock (1983D) at La Silla T

- 12 the visual by 1.3 mag). Like for the other SOor variables we M explain this particular finding by the very high mass loss (M = Bol 5 6.10- M0 yr-') during outburst. The variations in the visual are caused by bolometric flux redistribution in the envelope whilst -10 the bolometric luminosity remains practically constant. The location of R127 in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram together with the other two known SOor variables of the LMC -B are shown in fig. 8. We note that Walborn classified R127 as an Of or alterna tively as a late WN-type star. This indicates that the star is a late Of star evolving right now towards a WN star. Since we have -6 detected an SOor-type outburst of this star we conclude that this transition is not a smooth one but is instead accompanied '.8 '.6 4.0 3.6 by the occasional ejection of dense envelopes. Fig. 8: Location of the newly discovered S Dar variable R 127 in the References Hertzsprung-Russell diagram in comparison with the other two estab lished SOor variables of the LMG. Also included in the figure is the Conti, P. S.: 1976, Mem. Soc. Roy. Sei. Liege 9,193. upper envelope of known stellar absolute bolometric magnitudes as Dunean, J. C.: 1922, Publ. Astron. Soc. Pacific 34, 290. derived byHumphreys andDavidson (1979). The approximateposition Hubble, E., Sandage, A.: 1953, Astrophys. J. 118, 353. o( the late WN-type stars is also given. Humphreys, R. M., Davidson, K.: 1979, Astrophys. J. 232,409. Lamers, H. -

World Space Observatory %Uf02d Ultraviolet Remains Very Relevant

WORLD SPACE OBSERVATORY-ULTRAVIOLET Boris Shustov, Ana Inés Gómez de Castro, Mikhail Sachkov UV observatories aperture pointing mode , Å OAO-2 1968.12 - 1973.01 20 sp is 1000-4250 TD-1A 1972.03 - 1974.05 28 s is 1350-2800+ OAO-3 1972.08 - 1981.02 80 p s 900-3150 ANS 1974.08 - 1977.06 22 p s 1500-3300+ IUE 1978.01 - 1996.09 45 p s 1150-3200 ASTRON 1983.03 - 1989.06 80 p s 1100-3500+ EXOSAT 1983.05 - 1986. 2x30 p is 250+ ROSAT 1990.06 - 1999.02 84 sp i 60- 200+ HST 1990.04 - 240 p isp 1150-10000 EUVE 1992.06 - 2001.01 12 sp is 70- 760 ALEXIS 1993.04 - 2005.04 35 s i 130- 186 MSX 1996.04 - 2003 50 s i 1100-9000+ FUSE 1999.06 - 2007.07 39х35 (4) p s 905-1195 XMM 1999.12 - 30 p is 1700-5500 GALEX 2003.04 - 2013.06 50 sp is 1350-2800 SWIFT 2004.11 - 30 p i 1700-6500 2 ASTROSAT/UVIT UVIT - UltraViolet Imaging Telescopes (on the ISRO Astrosat observatory, launch 2015); Two 40cm telescopes: FUV and NUV, FOV 0.5 degrees, resolution ~1” Next talk by John Hutchings! 3 4 ASTRON (1983 – 1989) ASTRON is an UV space observatory with 80 cm aperture telescope equipped with a scanning spectrometer:(λλ 110-350 nm, λ ~ 2 nm) onboard. Some significant results: detection of OH (H2O) in Halley comet, UV spectroscopy of SN1987a, Pb lines in stellar spectra etc. (Photo of flight model at Lavochkin Museum).5 “Spektr” (Спектр) missions Federal Space Program (2016-2025) includes as major astrophysical projects: Spektr-R (Radioastron) – launched in 2011. -

THE GAMMA RAY EXPERIMENT for the SMALL ASTRONOMY SATELLITE B (SAS-B) C. E. Fichtel, C. H..~Hrmann, R. C. Hartman, D. A. Kniffen

THE GAMMA RAY EXPERIMENT FOR THE SMALL ASTRONOMY SATELLITE B (SAS-B) C. E. Fichtel, C. H.. ~hrmann, R. C. Hartman, D. A. Kniffen, H. B. Ogelman*, and R. W. Ross Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md. 20771 Abstract A magnetic core digitized spark chamber gamma ray telescope has been developed for satellite use and will be flown on SAS-B in less than one year. The SAS-B detector will have the following characteristics: Effective area ~ 500 cm2 , solid angle = ~ SR; Efficiency (high energy) ~ 0.29; and time resolution of better than two milliseconds. A detailed picture of the galactic plane in gamma rays should be obtained with this experiment, and a study of point sources, including short bursts of gamma rays from supernovae explosions, will also be possible. 1. Introduction The SAS-B gamma ray telescope represents the first satellite version of a planned evolution of a gamma ray digitized spark chamber telescope which began with the development of a balloon borne instrument. The telescope is aimed at the study of gamma rays whose energy exceeds about 20 MeV. In the early 1960's, it was realized that the celestial gamma ray intensity was very low compared to the high background of cosmic ray particles and earth albedo. For this reason, a picture type detector seemed to be needed to identify unambiguously the electron pair produced by the gamma ray and to study its properties - particularly to obtain a measure of the energy and arrival direction of the gamma ray. In addition, the secondary gamma ray flux produced by cosmic rays in the atmosphere, even at the altitudes of the present large balloons, severely limits the gamma ray astronomy which can be accomplished with balloons and dictates that gamma ray ~stronomy must ultimately be accomplished with detector systems on satellites. -

Calibration Against Spectral Types and VK Color Subm

Draft version July 19, 2021 Typeset using LATEX default style in AASTeX63 Direct Measurements of Giant Star Effective Temperatures and Linear Radii: Calibration Against Spectral Types and V-K Color Gerard T. van Belle,1 Kaspar von Braun,1 David R. Ciardi,2 Genady Pilyavsky,3 Ryan S. Buckingham,1 Andrew F. Boden,4 Catherine A. Clark,1, 5 Zachary Hartman,1, 6 Gerald van Belle,7 William Bucknew,1 and Gary Cole8, ∗ 1Lowell Observatory 1400 West Mars Hill Road Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA 2California Institute of Technology, NASA Exoplanet Science Institute Mail Code 100-22 1200 East California Blvd. Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3Systems & Technology Research 600 West Cummings Park Woburn, MA 01801, USA 4California Institute of Technology Mail Code 11-17 1200 East California Blvd. Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 5Northern Arizona University Department of Astronomy and Planetary Science NAU Box 6010 Flagstaff, Arizona 86011, USA 6Georgia State University Department of Physics and Astronomy P.O. Box 5060 Atlanta, GA 30302, USA 7University of Washington Department of Biostatistics Box 357232 Seattle, WA 98195-7232, USA 8Starphysics Observatory 14280 W. Windriver Lane Reno, NV 89511, USA (Received April 18, 2021; Revised June 23, 2021; Accepted July 15, 2021) Submitted to ApJ ABSTRACT We calculate directly determined values for effective temperature (TEFF) and radius (R) for 191 giant stars based upon high resolution angular size measurements from optical interferometry at the Palomar Testbed Interferometer. Narrow- to wide-band photometry data for the giants are used to establish bolometric fluxes and luminosities through spectral energy distribution fitting, which allow for homogeneously establishing an assessment of spectral type and dereddened V0 − K0 color; these two parameters are used as calibration indices for establishing trends in TEFF and R. -

UV and Infrared Astronomy

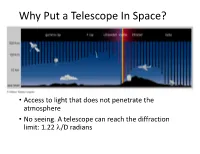

Why Put a Telescope In Space? • Access to light that does not penetrate the atmosphere • No seeing. A telescope can reach the diffraction limit: 1.22 l/D radians Astronomy in Space. I. UV Astronomy Ultraviolet Astronomy 912-3650 Å (Lyman Limit to Balmer jump) • Continuua of hot stars (spectral types O,B,A) • H I Lyman lines (1-n transitions) • Resonance lines of Li-like ions C IV, N V, O VI • H2 Lyman and Werner bands Normal incidence optics • Special UV-reflective coatings The Far Ultraviolet 912 to 1150 Å • Defined by Lyman limit, MgF cutoff at 1150 Å • LiF + Al reflects longward of 1050 Å • SiC reflects at shorter wavelengths The Astronomy Quarterly, Vol. 7, pp. 131-142, 1990 0364-9229f90 $3.00+.00 Printed in the USA. All rights reserved. Copyright (c) 1990 Pergamon Press plc ASTRONOMICAL ADVANTAGES History OFAN • 9/1/1946: Lyman Spitzer EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL OBSERVATORY proposed a Space Telescope in LYMAN SPITZER, Jr. ’ a Report to project Rand This study points out, in a very preliminary way, the results that might be expected from astronomical measurements made with a satellite • 1966: Spitzer (Princeton) vehicle. The discussion is divided into three parts, corresponding to three different assumptions concerning the amount of instrumentation provided. chairs NASA Ad Hoc In the first section it is assumed that no telescope is provided; in the second a 10-&h reflector is assumed; in the third section some of the results Committee on the "Scientific obtainable with a large reflecting telescope, many feet in diameter, and revolving about the earth above the terrestrial atmosphere, are briefly Uses of the Large Space sketched.