Arrabales Using the Planes De Almas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 Hours)

BINONDO FOOD TRIP (4 hours) Eat your way around Binondo, the Philippines’ Chinatown. Located across the Pasig River from the walled city of Intramuros, Binondo was formally established in 1594, and is believed to be the oldest Chinatown in the world. It is the center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino-Chinese merchants, and given the historic reach of Chinese trading in the Pacific, it has been a hub of Chinese commerce in the Philippines since before the first Spanish colonizers arrived in the Philippines in 1521. Before World War II, Binondo was the center of the banking and financial community in the Philippines, housing insurance companies, commercial banks and other financial institutions from Britain and the United States. These banks were located mostly along Escólta, which used to be called the "Wall Street of the Philippines". Binondo remains a center of commerce and trade for all types of businesses run by Filipino- Chinese merchants and is famous for its diverse offerings of Chinese cuisine. Enjoy walking around the streets of Binondo, taking in Tsinoy (Chinese-Filipino) history through various Chinese specialties from its small and cozy restaurants. Have a taste of fried Chinese Lumpia, Kuchay Empanada and Misua Guisado at Quick Snack located along Carvajal Street; Kiampong Rice and Peanut Balls at Café Mezzanine; Kuchay Dumplings at Dong Bei Dumplings and the growing famous Beef Kan Pan of Lan Zhou La Mien. References: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Binondo,_Manila TIME ITINERARY 0800H Pick-up -

MANILA BAY AREA SITUATION ATLAS December 2018

Republic of the Philippines National Economic and Development Authority Manila Bay Sustainable Development Master Plan MANILA BAY AREA SITUATION ATLAS December 2018 MANILA BAY AREA SITUATION ATLAS December 2018 i Table of Contents Preface, v Administrative and Institutional Systems, 78 Introduction, 1 Administrative Boundaries, 79 Natural Resources Systems, 6 Stakeholders Profile, 85 Climate, 7 Institutional Setup, 87 Topography, 11 Public-Private Partnership, 89 Geology, 13 Budget and Financing, 91 Pedology, 15 Policy and Legal Frameworks, 94 Hydrology, 17 National Legal Framework, 95 Oceanography, 19 Mandamus Agencies, 105 Land Cover, 21 Infrastructure, 110 Hazard Prone Areas, 23 Transport, 111 Ecosystems, 29 Energy, 115 Socio-Economic Systems, 36 Water Supply, 119 Population and Demography, 37 Sanitation and Sewerage, 121 Settlements, 45 Land Reclamation, 123 Waste, 47 Shoreline Protection, 125 Economics, 51 State of Manila Bay, 128 Livelihood and Income, 55 Water Quality Degradation, 129 Education and Health, 57 Air Quality, 133 Culture and Heritage, 61 Habitat Degradation, 135 Resource Use and Conservation, 64 Biodiversity Loss, 137 Agriculture and Livestock, 65 Vulnerability and Risk, 139 Aquaculture and Fisheries, 67 References, 146 Tourism, 73 Ports and Shipping, 75 ii Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank ISF Informal Settlers NSSMP National Sewerage and Septage Management Program AHLP Affordable Housing Loan Program IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature NSWMC National Solid Waste Management Commission AQI Air Quality Index JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency OCL Omnibus Commitment Line ASEAN Association of Southeast Nations KWFR Kaliwa Watershed Forest Reserve OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development BSWM Bureau of Soils and Water Management LGU Local Government Unit OIDCI Orient Integrated Development Consultants, Inc. -

Population by Barangay National Capital Region

CITATION : Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population Report No. 1 – A NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay August 2016 ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 1 – A 2015 Census of Population Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 Philippine Statistics Authority TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword v Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 vii List of Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Explanatory Text xiii Map of the National Capital Region (NCR) xxi Highlights of the Philippine Population xxiii Highlights of the Population : National Capital Region (NCR) xxvii Summary Tables Table A. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates for the Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities: 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxi Table B. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates by Province, City, and Municipality in National Capital Region (NCR): 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxiv Table C. Total Population, Household Population, -

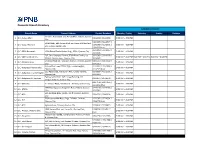

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE Branch Name Present Address Contact Numbers Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday Holidays cor Gen. Araneta St. and Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon 1 Q.C.-Cubao Main 911-2916 / 912-1938 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 912-3070 / 912-2577 / SRMC Bldg., 901 Aurora Blvd. cor Harvard & Stanford 2 Q.C.-Cubao-Harvard 913-1068 / 912-2571 / 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Sts., Cubao, Quezon City 913-4503 (fax) 332-3014 / 332-3067 / 3 Q.C.-EDSA Roosevelt 1024 Global Trade Center Bldg., EDSA, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 332-4446 G/F, One Cyberpod Centris, EDSA Eton Centris, cor. 332-5368 / 332-6258 / 4 Q.C.-EDSA-Eton Centris 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM EDSA & Quezon Ave., Quezon City 332-6665 Elliptical Road cor. Kalayaan Avenue, Diliman, Quezon 920-3353 / 924-2660 / 5 Q.C.-Elliptical Road 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 924-2663 Aurora Blvd., near PSBA, Brgy. Loyola Heights, 421-2331 / 421-2330 / 6 Q.C.-Katipunan-Aurora Blvd. 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 421-2329 (fax) 335 Agcor Bldg., Katipunan Ave., Loyola Heights, 929-8814 / 433-2021 / 7 Q.C.-Katipunan-Loyola Heights 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 433-2022 February 07, 2014 : G/F, Linear Building, 142 8 Q.C.-Katipunan-St. Ignatius 912-8077 / 912-8078 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Katipunan Road, Quezon City 920-7158 / 920-7165 / 9 Q.C.-Matalino 21 Tempus Bldg., Matalino St., Diliman, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 924-8919 (fax) MWSS Compound, Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon 927-5443 / 922-3765 / 10 Q.C.-MWSS 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 922-3764 SRA Building, Brgy. -

To Download the Program

C O N V E N T I O N PPP RRR OOO GGG RRR AAA MMM NATCON DAY 0 Time Event Venue 8:30AM -12:00NN Tripartite Meeting 3rd Floor Meeting Rooms UAP, PRBOA, CODHASP UAP National Headquarters 8:30AM -12:00NN Chapter Presidents’ Assembly Teatro Arkitekto UAP National Headquarters 12:00NN -1:00PM Lunch 1:00 -5:00PM CODHASP Meeting and 3rd Floor Meeting Rooms General Assembly UAP National Headquarters 2:30 -8:00PM National Board of Directors’ Meeting 6th Floor Meeting Room UAP National Headquarters ARKILYMPICS Time Event Venue 7:30 AM Delegates Assembly UAP National Headquarters To Quezon City Sports Club 8: 00 -9:00AM Registration Quezon City Sports Club Opening Ceremonies Invocation National Anthem National Opening Remarks Oath Of Sportsmanship 9:00AM -12:00NN Morning Games 12:00NN -1:00PM Lunch 1:00 -4:00PM Afternoon Games Quezon City Sports Club 4:00 -5:00PM Closing / Awarding Ceremonies Quezon City Sports Club C O N V E N T I O N PPP RRR OOO GGG RRR AAA MMM NATCON DAY 1 Time Event Venue 8:00AM -6:00PM Registration SMX Convention Center Meeting Rooms 4-6 Meeting Rooms 7-9 10:00AM -12:00NN Opening Ceremonies SMX Convention Center Function Halls 2-5 12:00NN -1:00PM Lunch SMX Convention Center Function Halls 2-5 1:30 -2:00PM CONEX Opening Ceremonies SMX Convention Center Halls 1-4 3:00 -5:00PM Plenary Seminar (CPD Session 1) SMX Convention Center Keynote Address Function Halls 2-5 SIGASIG: A Zeal for Excellence Francis J. Kong 5:00 -7:00PM Honor Dinner SMX Convention Center Function Halls 2-5 7:00 -10:00PM Dinner and Fellowship SMX Convention Center -

Balikbayan Plus Program

BALIKBAYAN PLUS PROG RAM ESTABLISHMENT GUIDE ( JANUARY 29, 2019 ) VASQUEZ SKIN & BODY (Dec.01, 2018 - Jan. 07, 2019) AZALEA HOTELS & BEAUTY & WELLNESS CENTER c) Marine Voyage 15 - Oceanarium, RESIDENCES (Baguio City) ( Airport Citimall & BF Symphony Evening Show, Sea Lion - Mr. Richard Labiano Homes, Paranaque City ) Show, Sharks and Rays Dry Encounter, - Room accommodation- 40% OFF BIOESSENCE - Mr. John Gonzales All star Bird Show, Birds of Prey - Until December 31, 2018 - 20% OFF in Cosmetic Surgery Kingdom, Penguin Talk Show, Trails to - +632.579.4890* 632.925.8352 (All Branches) BF Homes- Procedures Antarctica: Penguin Exhibits & NOTE: For renewal 0949.957.6482;Cainta-0949.8893368; -10% OFF in Non-Surgical-Dermatologic Christmas Village, Fish Spa, Back of the Bacoor-0949.309.6880;Dasmariñas- Procedures House, World of Creepy Crawlies, The 0918.467.9978; Megamall-634.3311; - Until August 31, 2019 Bird House, The Barn Yard, Neon Ride Serenity Spa Cainta-0949.889.3367; - +632.829.9755 / 0917.3299753 / (New Attraction) AZALEA HOTELS & Serenity Spa Batangas- 0949. 889. 0917.3299755 -Php880 for individual rates and RESIDENCES ( Boracay ) 3380; Binondo-0949.889.3372;BF group rates (March 01 - Nov. 30, 2018 - Mr. Richard Labiano Homes-836.9842; Davao-0932.860. & Jan.08-Feb.28, 2019)/ Php950 for - Room accommodation- 40% OFF 6252; LPL Tower Makati-815.2256; ENTERTAINMENT Peak Season Rate Individual and - Until December 31, 2018 Group (Dec.01, 2018 - Jan. 07, 2019) Las Piñas-872.2341;Waltermart For inquiries: +632..579.4890* Pampanga- 0920.290.1902;SMTaytay- MANILA OCEAN PARK - Until February 28, 2019 632.925.8352 570.6362;SM Cebu-032.416.1885; (Manila ) +632.585.0069 *+632.567.7777 NOTE: For renewal Shoppesvile Greenhills- - Mr. -

Store Store Business Address Business Center Location Inside

Business Center Location Store Store Business Address inside Robinsons Department Store 1 RDS RP Ermita Robinsons Place, M. Adriatico St., Ermita, Manila 1000 Midtown Wing Level 1 near Ladies Shoes Section RDS Tutuban 2 Tutuban Center, Loop Road West, C.M. Recto, Tondo, Manila 1012 Level 2 beside Luggage Section Center Mall RDS Festival Mall 3 Filinvest Alabang, Muntinlupa City Level 2 beside Snacks and Toys Section Alabang 4 RDS RP Pioneer EDSA corner Pioneer St., Mandaluyong City Level 2 beside Intimate Apparel Section 5 RDS RP Magnolia UG, Level 2 &3, Aurora Boulevard, New Manila, Q.C. Upper Ground Floor Near Men’s Furnishing Section RDS Victoria Mall 6 3rd Floor Galeria Victoria Bldg JP Rizal Balanga City, Bataan Level 3 beside Toys and Infants’ Wear Section Bataan 7 RDS RP Santiago Maharlika Hi-way, Brgy Mabini, Santiago City, Isabela Level 1 beside Luggage section 8 RDS RP Imus Aguinaldo Highway, Imus, Cavite Level 2 near Luggage and Mens Accessories Section RDS RP Level 1 near West Entrance, Gapan-Olangapo Road Brgy. San Jose, San 9 Level 1 near West Entrance Pampanga Fernando Pampanga Robinsons Town Mall, Lopez Avenue, Batong Malake, Los Baños, Laguna 10 RDS RP Los Banos Level 2 beside gift-wrapping section 4030 RDS Nepomall 11 St. Joseph Cor Dona Teresa St Sto Rosario Angeles City, Pampanga Level 2 beside Athletic Shoes Section Angeles 12 RDS RP Lipa Mataas na Lupa, Lipa City Level 1 near Luggage Area and Plasticware Section RDS RP 13 Km 111 Maharlika Highway, Cabanatuan City Level 2 beside Luggage Section Cabanatuan RDS RP Ilocos 14 Brgy. -

BY AIRMAIL H.E. Rodrigo Duterte President of the Republic Malacañang Palace, JP Laurel St., San Miguel MANILA, PHILIPPINES E-Ma

BY AIRMAIL H.E. Rodrigo Duterte President of the Republic Malacañang Palace, JP Laurel St., San Miguel MANILA, PHILIPPINES E-mail: [email protected] Amsterdam, 13 August 2019 Your Excellency, Lawyers for Lawyers is an independent and non-political foundation which seeks to promote the proper functioning of the rule of law by pursuing freedom and independence of the legal profession. We support lawyers worldwide who face reprisals, improper interferences or unreasonable restrictions in the execution of their profession. Lawyers for Lawyers was granted Special Consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council in July 2013. Lawyers for Lawyers has been closely monitoring the situation of lawyers and the legal profession in the Philippines for many years. We are deeply concerned about the increasing attacks against lawyers, the labelling of lawyers as ‘enemy of the State’, and the oppressive working environment they face since the start of your administration. We have reason to believe that these attacks are connected to their legitimate activities and professional duties as lawyers. On July 23, 2019, our colleague Atty. Anthony Trinidad, was killed in an attack by unidentified motorcycle-riding men in Guihulngan City in Negros Oriental. He was on his way home from a court hearing. Prior to being attacked, Atty Trinidad had been receiving death threats in connection to the cases he was handling, some of which are that of political prisoners in the region. Atty. Trinidad had also been tagged as a supporter of communist rebels on Negros Island. Earlier in 2018, his name was said to be included in a ‘hit list’ of an alleged anti-communist group called Kawsa Guihulnganon Batok Komunista (KAGUBAK). -

Maq. 37 Enteraok 15/12/15 12:38 Página 15

Maq. 37 enteraok 15/12/15 12:38 Página 15 Revista de Estudios Taurinos N.º 37, Sevilla, 2015, págs. 15-64 APORTACIÓN DOCUMENTAL A LA HISTORIA TAURINA DE LAS ISLAS FILIPINAS* Francisco Miguel Aránega Castilla** «La ignorancia en que viven los más de los escri- tores contemporáneos de asuntos filipinos, es tanta, que creen que en aquel país las corridas de toros son cosa recientísima.» W.E. Retana y Gamboa1. I. INTRODUCCIÓN on muy escasas las personas conocedoras del pasado taurómaco de la Republica de Filipinas, pero cierto S es que esta tradición, exportada desde España, per- maneció en el archipiélago por más de tres siglos. La antigua colonia, descubierta en 1521 y colonizada desde 1565, poco a poco se adaptó a las nuevas costumbres españolas: empe- zando por su religión, vida doméstica, ocupaciones diarias y por supuesto sus diversiones, fiestas y juegos. Claro está que las corridas de toros serían parte de estas tradiciones, aunque no contarían con muchos adeptos autóctonos, sino que serían los * Una versión anterior de este trabajo fue presentada a las XIV Jornadas de Historia en Llerena. V Centenario del Descubrimiento de la Mar del Sur (1513-2013), celebrado en Llerena del 25 al 26 de octubre de 2013, con el título Reseñas de la Tauromaquia en Filipinas (1619-1957). La revisión de nueva docu- mentación permitió la realización de este nuevo trabajo ampliado. ** Centro de Estudios Linarenses, Linares (Jaén). fmaranegacastilla@hot- mail.com. 1 Con estas palabras Retana realiza una de las muchas anotaciones con las que acompañó la edición del texto inédito de su admirado Joaquín Martínez de Zúñiga (1760-1818), quien sería uno de los primeros en señalar la presencia de festejos taurinos en Filipinas. -

Intramuros During the American Colonization

Intramuros during the American Colonization Irene G. BORRAS1 University of Santo Tomas MANILA ABSTRACT Intramuros, located in the capital city of the Philppines, became a symbolic siting that represents one’s social status and importance in society during the Spanish colonization. Also known as the “Walled City,” Intramuros is home to the oldest churches, schools, and government offices in the Philippines. When the Americans decided to colonized the Philippines, they did not have to conquer all the islands of the archipelago. They just have to secure Intramuros and the entire country fell to another colonizer. The goal of this paper is to identify the effects of creating a “center” or a city––from the way it is planned and structured––on one’s way of thinking and later on the attitude of the people towards the city. Specifically, the paper will focus on the important and symbolic structures near and inside the “walled city” and its effects on the mindset of the people towards the institutions that they represent. The paper will focus on the transition of Intramuros from a prestigious and prominent place during the Spanish colonization to an ordinary and decaying “Walled City” during the American period. Significantly, the paper will discuss the development of “Extramuros” or those settlements outside the walled city. It will give focus on the planning of Manila by Daniel Burnham during the American period which was basically focused on the development of the suburbs outside Intramuros. The paper will also discuss the important establishments built outside the Walled City during the American period. -

DEPARTMENT of PUBLIC WORKS and HIGHWAYS SOUTH MANILA DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Th 8 Street, Port Area, Manila

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS SOUTH MANILA DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION th 8 Street, Port Area, Manila INVITATION TO BID 1. Contract ID No. 17OH0113 Contract Name: Completion/Repair/Renovation/Improvement of Various Facilities at DPWH Central Office Building- Civil and Sanitary/Plumbing Works, Bonifacio Drive, Port Area, Manila Contract Location: Manila City Scope of Work: Completion/Repair/Renovation/Improvement of Various Source of Fund and Year: 01101101-Regular Agency Fund-General Fund-New General Appropriations- Specific Budgets of National Government Agencies Approved Budget for the Contract (ABC): (₱ 31,392,668.06) Contract Duration: 360 cal. Days Co t of Bid Docu ent : ₱ 25,000.00 2. Contract ID No. 17OH0114 Contract Name: Proposed Rainwater Collector System at: a) Silahis ng Katarungan, 1520 Paz St. Paco, Manila; b) Technological University of the Philippines, Ayala Blvd., Ermita, Manila; c) Normal University Taft Ave., corner Ayala Blvd., Ermita, Manila; d) Bagong Barangay Elementary School, J. Zamora, Pandacan, Manila; e) Bagong Diwa Elementary School 2244 Linceo St., Pandacan, Manila; f) Beata Elementary School, Beata corner Certeza St., Pandacan, Manila; g) T. Earnshaw Elementary School, A. Bautista St., Punta, Sta. Ana, Manila; h) Pio del Pilar Elementary School, Pureza St., Sta. Mesa, Manila; i) Geronimo Santiago Elementary School, J. Nepomuceno St., San Miguel, Manila; j) J. Zamora Elementary School, Zamora St., Pandacan, Manila; k) Sta. Ana Elementary School, M. Roxas St., Sta. Ana, Manila; l) Mariano Marcos Memorial High School, 2090 Dr. M. Carreon St., Sta. Ana, Manila; m) C.P. Garcia High School, Jesus St., Pandacan, Manila; n) Benigno Aquino Elementary School, BASECO Compound, Port Area, Manila; o) E. -

The History of Pleasant Grove City Neighborhoods

The History of Pleasant Grove City Neighborhoods 0 The History of Battle Creek by Beth R. Olsen Transient Timpanogos Ute Indians seasonably hunted and lived around the canyons above what is now Pleasant Grove. Between and above the two east canyons lay a large flat area known as the summer Indian campgrounds. It is the mouth of the south canyon that Roman Nose and Blue Shirt and those of their lodges, constituting seventeen members, had camped the winter and the first few days of March 1849. Little Chief, logged near the south end of Utah Lake with his group, had driven this renegade group from his main group for living off white men’s cattle that winter. The Indians had stolen cattle from the Mormon Church’s herds, wintering at Willow Creek (Draper). Little Chief made known to O.B. Huntington that he wanted the whites to kill the renegade group lest Little Chief’s band be blamed for the theft and retribution be taken on them. Upon receiving information that identified the guilty party, Brigham Young called the Council of Fifty and appointed John Scott to lead the group in search of the guilty parties. Scott’s group left Salt Lake City March 1, traveling toward the Indian inhabited Utah Valley. After stopping to supply themselves with good horses and fresh meat from the church’s herds at Willow Creek, they entered Utah Valley on March 3, by way of the Jordon Narrows. After a search of the northern end of the valley, they visited with Little Chief at the south of Utah Lake near Provo River.