Hollywood and the Dawn of Television 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IS/SONY in High Gear W/Japanese Market on Eve Ur Inch Disks Bow

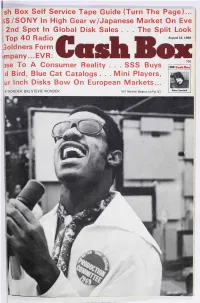

i sh Box Self Service Tape Guide (Turn The Page) ... IS/SONY In High Gear w/Japanese Market On Eve 2nd Spot In Global Disk Sales . The Split Look August 16, 1969 i Top 40 Radio ,;oldners Form ash.,mpany...EVR: )se To A Consumer Reality ... SSS Buys Ott Cash Box754 d Bird, Blue Cat Catalogs ... Mini Players, ur Inch Disks Bow On European Markets... Peter Sarstedt E WONDER: BIG STEVIE WONDER Intl Section Begins on Pg. 61 www.americanradiohistory.com The inevitable single from the group that brought you "Young Girl" and "WomanYVoman:' EC "This Girl Is Dir Ai STA BII aWoman Now7 hbAn. by Gary Puckett COiN and The Union Gap. DEE On Columbia Records* Di 3 II Lodz,' Tel: 11A fie 1%. i avb .» o www.americanradiohistory.com ///1\\ %b\\ ISM///1\\\ ///=1\\\ Min 111 111\ //Il11f\\ 11111111111111 1/11111 III111 MUSIC -RECORD WEEKLY ii INTERNATIONAL milli 1IUUIII MI/I/ MIII II MU/// MUMi M1111/// U1111D U IULI glia \\\1197 VOL. XXXI - Number 3/August 16, 1969 Publication Office / 1780 Broadway, New York, New York 10019 / Telephone JUdson 6-2640 / Cable Address: Cash Box, N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL MARV GOODMAN Cash Box Assoc. Editor JOHN KLEIN BOB COHEN BRUCE HARRIS Self- Service EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS MIKE MARTUCCI ANTHONY LANZETTA Tape Guide ADVERTISING BERNIE BLAKE Director of Advertising ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES STAN SOIFER, New York BILL STUPER, New York HARVEY GELLER, Hollywood Much of the confusion facing first - 8 -TRACK CARTRIDGES: Using the WOODY HARDING unit tape consumers lies in the area same speed and thickness of tape Art Director of purchaser education. -

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

Global Semiconductor Industry | Accenture

GLOBALITY AND COMPLEXITY of the Semiconductor Ecosystem The semiconductor industry is a truly global affair. Around the world, semiconductor chip designers use intellectual property (IP) licenses and design verification to provide designs to wafer fabricators, which use raw silicon, photomasks, and equipment to create chips for package manufacturing to assemble with printed circuit board (PCB) substrates for delivery to end customers. In fact, components for a chip could travel more than 25,000 miles by the time it finds its way into a television set, mobile phone, automobile, computer, or any of the millions of products that now rely on chips to operate (Figure 1). 2 | Globality and Complexity of the Semiconductor Ecosystem Figure 1: Components for a chip could travel more than 25,000 miles before completion IP Licenses Euipment Modules Package Raw Silicon Manufacturing PC Substrates Asembly Standard Products and Test components Wafer Fabrication Equipment Chip Design Design Verification Photomask Wafer Manufacturing Fabrication The Global Semiconductor Alliance (GSA) and Accenture have teamed up to conduct a joint study on the globality and complexity of the semiconductor ecosystem to explore the interdependencies and benefits of the cross-border partnerships required to produce semiconductors, as well as to illustrate what’s needed to keep this global ecosystem operating efficiently and profitably. Industry executives can use this study to inform their company strategies, as well as to educate non-semiconductor partners, including policy makers, on the nature of their business to promote a better understanding of the important role semiconductors play in everyday life and on the globe-spanning ecosystem that’s needed to produce them. -

Thursday 15 October 11:00 an Introduction to Cinerama and Widescreen Cinema 18:00 Opening Night Delegate Reception (Kodak Gallery) 19:00 Oklahoma!

Thursday 15 October 11:00 An Introduction to Cinerama and Widescreen Cinema 18:00 Opening Night Delegate Reception (Kodak Gallery) 19:00 Oklahoma! Please allow 10 minutes for introductions Friday 16 October before all films during Widescreen Weekend. 09.45 Interstellar: Visual Effects for 70mm Filmmaking + Interstellar Intermissions are approximately 15 minutes. 14.45 BKSTS Widescreen Student Film of The Year IMAX SCREENINGS: See Picturehouse 17.00 Holiday In Spain (aka Scent of Mystery) listings for films and screening times in 19.45 Fiddler On The Roof the Museum’s newly refurbished digital IMAX cinema. Saturday 17 October 09.50 A Bridge Too Far 14:30 Screen Talk: Leslie Caron + Gigi 19:30 How The West Was Won Sunday 18 October 09.30 The Best of Cinerama 12.30 Widescreen Aesthetics And New Wave Cinema 14:50 Cineramacana and Todd-AO National Media Museum Pictureville, Bradford, West Yorkshire. BD1 1NQ 18.00 Keynote Speech: Douglas Trumbull – The State of Cinema www.nationalmediamuseum.org.uk/widescreen-weekend 20.00 2001: A Space Odyssey Picturehouse Box Office 0871 902 5756 (calls charged at 13p per minute + your provider’s access charge) 20.00 The Making of The Magnificent Seven with Brian Hannan plus book signing and The Magnificent Seven (Cubby Broccoli) Facebook: widescreenweekend Twitter: @widescreenwknd All screenings and events in Pictureville Cinema unless otherwise stated Widescreen Weekend Since its inception, cinema has been exploring, challenging and Tickets expanding technological boundaries in its continuous quest to provide Tickets for individual screenings and events the most immersive, engaging and entertaining spectacle possible. can be purchased from the Picturehouse box office at the National Media Museum or by We are privileged to have an unrivalled collection of ground-breaking phoning 0871 902 5756. -

Television Device Ecologies, Prominence and Datafication: the Neglected Importance of the Set-Top Box

This is a repository copy of Television device ecologies, prominence and datafication: the neglected importance of the set-top box. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/146713/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Hesmondhalgh, D orcid.org/0000-0001-5940-9191 and Lobato, R (2019) Television device ecologies, prominence and datafication: the neglected importance of the set-top box. Media, Culture and Society, 41 (7). pp. 958-974. ISSN 0163-4437 https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719857615 © 2019, The Author(s). All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a paper accepted for publication in Media, Culture and Society. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Television device ecologies, prominence and datafication: the neglected importance of the set-top box David Hesmondhalgh, University of Leeds, UK Ramon Lobato, RMIT, Australia Accepted for publication by Media, Culture and Society, April 2019, due for online publication July 2019 Abstract A key element of the infrastructure of television now consists of various internet-connected devices, which play an increasingly important role in the distribution, selection and recommendation of content to users. The aim of this article is to locate the emergence of streaming devices within a longer timeframe of television hardware devices and infrastructures, by focusing on the evolution of one crucial category of such devices, television set-top boxes (STBs). -

CINERAMA: the First Really Big Show

CCINEN RRAMAM : The First Really Big Show DIVING HEAD FIRST INTO THE 1950s:: AN OVERVIEW by Nick Zegarac Above left: eager audience line ups like this one for the “Seven Wonders of the World” debut at the Cinerama Theater in New York were short lived by the end of the 1950s. All in all, only seven feature films were actually produced in 3-strip Cinerama, though scores more were advertised as being shot in the process. Above right: corrected three frame reproduction of the Cypress Water Skiers in ‘This is Cinerama’. Left: Fred Waller, Cinerama’s chief architect. Below: Lowell Thomas; “ladies and gentlemen, this is Cinerama!” Arguably, Cinerama was the most engaging widescreen presentation format put forth during the 1950s. From a visual standpoint it was the most enveloping. The cumbersome three camera set up and three projector system had been conceptualized, designed and patented by Fred Waller and his associates at Paramount as early as the 1930s. However, Hollywood was not quite ready, and certainly not eager, to “revolutionize” motion picture projection during the financially strapped depression and war years…and who could blame them? The standardized 1:33:1(almost square) aspect ratio had sufficed since the invention of 35mm celluloid film stock. Even more to the point, the studios saw little reason to invest heavily in yet another technology. The induction of sound recording in 1929 and mounting costs for producing films in the newly patented 3-strip Technicolor process had both proved expensive and crippling adjuncts to the fluidity that silent B&W nitrate filming had perfected. -

GFA Courses 1

GFA Courses 1 GFA 2020. GFA Lighting & Electric. 6-0-6 Units. GFA COURSES This course is designed to equip students with the skills and knowledge of electrical distribution and set lighting on a motion picture or episodic Courses television set in order to facilitate their entry and advancement in the GFA 1000. Intr to On-Set Film Production. 6-0-6 Units. film business. Students will participate in goal oriented class projects This course is the first of an 18-credit hour certificate program which including power distribution, set protocol and etiquette, properly setting will provide an introduction to the skills used in on-set film production, lamps, department lingo, how to light a set to feature film standards, including all forms of narrative media which utilize film-industry standard motion picture photography, etc. Upon completion of this course, the organizational structure, professional equipment and on- set procedures. student will have a very solid and broad base of knowledge that includes, In addition to the use of topical lectures, PowerPoint presentations, but is not limited to, the equipment, techniques, communications, videos and hand-outs, the course will include demonstrations of specifications, etc. used in the set lighting department. The student will equipment and set operations as well as hands-on learning experiences. also have a virtually complete understanding of the behavior of light and Students will learn: film production organizational structure, job how to manipulate and control it to feature film standards. descriptions and duties in various film craft areas, names, uses and GFA 2030. Grip & Rigging. 6-0-6 Units. -

Pilot Season

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College Spring 2014 Pilot Season Kelly Cousineau Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cousineau, Kelly, "Pilot Season" (2014). University Honors Theses. Paper 43. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Pilot Season by Kelly Cousineau An undergraduate honorsrequirements thesis submitted for the degree in partial of fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts in University Honors and Film Thesis Adviser William Tate Portland State University 2014 Abstract In the 1930s, two historical figures pioneered the cinematic movement into color technology and theory: Technicolor CEO Herbert Kalmus and Color Director Natalie Kalmus. Through strict licensing policies and creative branding, the husband-and-wife duo led Technicolor in the aesthetic revolution of colorizing Hollywood. However, Technicolor's enormous success, beginning in 1938 with The Wizard of Oz, followed decades of duress on the company. Studios had been reluctant to adopt color due to its high costs and Natalie's commanding presence on set represented a threat to those within the industry who demanded creative license. The discrimination that Natalie faced, while undoubtedly linked to her gender, was more systemically linked to her symbolic representation of Technicolor itself and its transformation of the industry from one based on black-and-white photography to a highly sanctioned world of color photography. -

10. the Extraordinarily Stable Technicolor Dye-Imbibition Motion

345 The Permanence and Care of Color Photographs Chapter 10 10. The Extraordinarily Stable Technicolor Dye-Imbibition Motion Picture Color Print Process (1932–1978) Except for archival showings, Gone With the He notes that the negative used to make Wind hasn’t looked good theatrically since the existing prints in circulation had worn out [faded]. last Technicolor prints were struck in 1954; the “That negative dates back to the early ’50s 1961 reissue was in crummy Eastman Color when United Artists acquired the film’s distri- (the prints faded), and 1967’s washed-out bution rights from Warner Bros. in the pur- “widescreen” version was an abomination.1 chase of the old WB library. Four years ago we at MGM/UA went back to the three-strip Tech- Mike Clark nicolor materials to make a new internegative “Movies Pretty as a Picture” and now have excellent printing materials. All USA Today – October 15, 1987 it takes is a phone call to our lab to make new prints,” he says.3 In 1939, it was the most technically sophisti- cated color film ever made, but by 1987 Gone Lawrence Cohn With the Wind looked more like Confederates “Turner Eyes ’38 Robin Hood Redux” from Mars. Scarlett and Rhett had grown green Variety – July 25, 1990 and blue, a result of unstable film stocks and generations of badly duplicated prints. Hair The 45-Year Era of “Permanent” styles and costumes, once marvels of spectral Technicolor Motion Pictures subtlety, looked as though captured in Crayola, not Technicolor. With the introduction in 1932 of the Technicolor Motion Not anymore. -

History of Widescreen Aspect Ratios

HISTORY OF WIDESCREEN ASPECT RATIOS ACADEMY FRAME In 1889 Thomas Edison developed an early type of projector called a Kinetograph, which used 35mm film with four perforations on each side. The frame area was an inch wide and three quarters of an inch high, producing a ratio of 1.37:1. 1932 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences made the Academy Ratio the standard Ratio, and was used in cinemas until 1953 when Paramount Pictures released Shane, produced with a Ratio of 1.66:1 on 35mm film. TELEVISION FRAME The standard analogue television screen ratio today is 1.33:1. The Aspect Ratio is the relationship between the width and height. A Ratio of 1.33:1 or 4:3 means that for every 4 units wide it is 3 units high (4 / 3 = 1.33). In the 1950s, Hollywood's attempt to lure people away from their television sets and back into cinemas led to a battle of screen sizes. Fred CINERAMA Waller of Paramount's Special Effects Department developed a large screen system called Cinerama, which utilised three cameras to record a single image. Three electronically synchronised projectors were used to project an image on a huge screen curved at an angle of 165 degrees, producing an aspect ratio of 2.8:1. This Is Cinerama was the first Cinerama film released in 1952 and was a thrilling travelogue which featured a roller-coaster ride. See Film Formats. In 1956 Metro Goldwyn Mayer was planning a CAMERA 65 ULTRA PANAVISION massive remake of their 1926 silent classic Ben Hur. -

MARK FREEMAN Encyclopedia of Science, Technology and Society Ooks&Sidtext=0816031231&Leftid=0

MARK FREEMAN Encyclopedia of Science, Technology and Society http://www.factsonfile.com/newfacts/FactsDetail.asp?PageValue=B ooks&SIDText=0816031231&LeftID=0 WIDESCREEN The scale of motion picture projection depends upon the inter- relationship of several factors: the size and aspect ratio of the screen; the gauge of the film; the type of lenses used for filming and projection; and the number of synchronized projectors used. These choices are in turn determined by engineering, marketing and aesthetic considerations. Aspect ratio is the width of the screen divided by the height. The classic standard aspect ratio was expressed as 1.33:1. Today most movies are screened as 1.85:1 or 2.35:1 (widescreen). Films shot in these ratios are cropped for television, which retains the classic ratio of 1.33:1. This cropping is accomplished either by removing a third of the image at the sides of the frame, or by "panning and scanning." In this process a technician determines which portion of a given frame should be included. "Letterboxing" creates a band of black above and below the televised film image. This allows the composition as originally photographed to be screened in video. The larger the film negative, the more resolution. Large film gauges allow greater resolution over a given size of projected image. In the 1890's film sizes varied from 12mm to as many as 80mm, before accepting Edison's 35mm standard. Today films continue to be screened in a variety of guages including Super 8mm, 16mm and Super 16mm, 35mm, 70mm and IMAX. Cinema and the fairground share a common history in the search for technologically based spectacles and attractions. -

Film Essay for "This Is Cinerama"

This Is Cinerama By Kyle Westphal “The pictures you are now going to see have no plot. They have no stars. This is not a stage play, nor is it a feature picture not a travelogue nor a symphonic concert or an opera—but it is a combination of all of them.” So intones Lowell Thomas before introduc- ing America to a ‘major event in the history of entertainment’ in the eponymous “This Is Cinerama.” Let’s be clear: this is a hyperbol- ic film, striving for the awe and majesty of a baseball game, a fireworks show, and the virgin birth all rolled into one, delivered with Cinerama gave audiences the feeling they were riding the roller coaster the insistent hectoring of a hypnotically ef- at Rockaway’s Playland. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. fective multilevel marketing pitch. rama productions for a year or two. Retrofitting existing “This Is Cinerama” possesses more bluster than a politi- theaters with Cinerama equipment was an enormously cian on the stump, but the Cinerama system was a genu- expensive proposition—and the costs didn’t end with in- inely groundbreaking development in the history of motion stallation. With very high fixed labor costs (the Broadway picture exhibition. Developed by inventor Fred Waller from employed no less than seventeen union projectionists), an his earlier Vitarama, a multi-projector system used primari- unusually large portion of a Cinerama theater’s weekly ly for artillery training during World War II, Cinerama gross went back into the venue’s operating costs, leaving sought to scrap most of the uniform projection standards precious little for the producers.