Mental Health, Gender Performance, and the Heterosexual Marketplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sarah Dessen

Featured Author: Sarah Dessen Along for the Ride by Sarah Dessen ISBN: 9780142415566 Binding: Paperback Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group Pub. Date: 2011-04-05 Pages: 432 Price: $10.99 A New York Times bestseller Up all night. Nights have always been Auden's time, her chance to escape everything that's going on around her. Then she meets Eli, a fellow insomniac, and he becomes her nocturnal tour guide. Now, with an endless supply of summer nights between them, almost anything can happen. "As with all Dessen's books, [this] is a must-have" --V ... Just Listen by Sarah Dessen ISBN: 9780142410974 Binding: Paperback Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group Pub. Date: 2008-02-28 Pages: 400 Price: $10.99 When Annabel, the youngest of three beautiful sisters, has a bitter falling out with her best friend—the popular and exciting Sophie—she suddenly finds herself isolated and friendless. but then she meets Owen—a loner, passionate about music and his weekly radio show, and always determined to tell the truth. And when they develop a friendship, Annabel is not only introduced to new music but is encouraged to listen to her own inner voice. With Owen’s help, can Annabel find the courage to speak out about what exactly happened the night her friendship with Sophie came to a screeching halt? Keeping the Moon by Sarah Dessen ISBN: 9780142401767 Binding: Paperback Publisher: Penguin Young Readers Group Pub. Date: 2004-05-11 Pages: 256 Price: $10.99 Fifteen-year-old Colie has never fit in. First, it was because she was fat. -

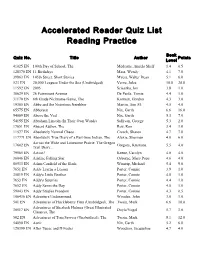

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Tuesday, February 12, 2013 12:12:12 PM School: Woodland Middle School

Quiz List—Reading Practice Page 1 Printed Tuesday, February 12, 2013 12:12:12 PM School: Woodland Middle School Reading Practice Quizzes Quiz Word Number Lang. Title Author IL ATOS BL Points Count F/NF 144408 EN 13 Curses Harrison, Michelle MG 5.3 16.0 107,383 F 136675 EN 13 Treasures Harrison, Michelle MG 5.3 11.0 73,953 F 8251 EN 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda Lee MG 5.2 1.0 5,229 NF 9801 EN 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne MG 6.4 1.0 6,130 NF 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George UG 8.9 17.0 88,942 F 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Verne, Jules MG 10.0 28.0 138,138 F (Unabridged) 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon MG 3.8 1.0 10,043 F 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague MG 3.3 1.0 10,339 F 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa MG 5.6 7.0 43,360 F 1302 EN 3 NBs of Julian Drew, The Deem*, James M. U 3.6 5.0 38,042 F 128675 EN 3 Willows: The Sisterhood Grows Brashares, Ann MG 4.5 9.0 63,547 F 8252 EN 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. MG 4.2 1.0 5,130 NF 901 EN Abduction Kehret*, Peg U 4.7 6.0 39,470 F 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette UG 6.0 8.0 50,015 F 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William MG 5.9 3.0 17,610 F 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth UG 6.6 16.0 99,206 F 14931 EN Abominable Snowman of Stine, R.L. -

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Friday, 03/04/11, 08:41 AM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Friday, 03/04/11, 08:41 AM Lakes Middle School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 17351 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BaseballBob Italia MG 5.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17352 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro BasketballBob Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17353 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro FootballBob Italia MG 6.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 17354 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro GolfBob Italia MG 5.6 1.0 English Nonfiction 17355 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro HockeyBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 17356 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro TennisBob Italia MG 6.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 17357 100 Unforgettable Moments in SummerBob Olympics Italia MG 6.5 1.0 English Nonfiction 17358 100 Unforgettable Moments in Winter OlympicsBob Italia MG 6.1 1.0 English Nonfiction 18751 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw MG 3.9 5.0 English Fiction 11101 A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald MG 7.7 1.0 English Nonfiction 8251 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair MG 5.2 1.0 English Nonfiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.7 4.0 English Fiction 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Wayne Coffey MG 6.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 523 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Jules Verne MG 10.0 28.0 English Fiction 9201 20,000 Leagues under the Sea (Pacemaker)Verne/Clare UG 4.3 2.0 English Fiction 34791 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. -

AR Quiz List by Title

Accelerated Reader Quiz List Reading Practice Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 41025 EN 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 128370 EN 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 4.1 7.0 39863 EN 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 5.1 6.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 11592 EN 2095 Scieszka, Jon 3.8 1.0 30629 EN 26 Fairmount Avenue De Paola, Tomie 4.4 1.0 31170 EN 6th Grade Nickname Game, The Korman, Gordon 4.3 3.0 19385 EN Abby and the Notorious Neighbor Martin, Ann M. 4.5 4.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 54089 EN Above the Veil Nix, Garth 5.3 7.0 54155 EN Abraham Lincoln (In Their Own Words) Sullivan, George 5.3 2.0 17651 EN Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 3.4 1.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 117771 EN Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian, The Alexie, Sherman 4.0 6.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary... 79585 EN Action! Keene, Carolyn 4.8 4.0 36046 EN Adaline Falling Star Osborne, Mary Pope 4.6 4.0 86533 EN Adam Canfield of the Slash Winerip, Michael 5.4 9.0 7651 EN Addy Learns a Lesson Porter, Connie 3.9 1.0 35819 EN Addy's Little Brother Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 7653 EN Addy's Surprise Porter, Connie 4.4 1.0 7652 EN Addy Saves the Day Porter, Connie 4.0 1.0 59043 EN Addy Studies Freedom Porter, Connie 4.3 0.5 106436 EN Adventure Underground Wooden, John 3.0 1.0 501 EN Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Unabridged), The Twain, Mark 6.6 18.0 Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (Great Illustrated 30517 EN Doyle/Vogel 5.7 3.0 Classics), The 502 EN Adventures of Tom Sawyer (Unabridged), The Twain, Mark 8.1 12.0 54090 EN Aenir Nix, Garth 5.2 6.0 120399 EN After Tupac and D Foster Woodson, Jacqueline 4.7 4.0 353 EN Afternoon of the Elves Lisle, Janet Taylor 5.0 4.0 14651 EN Afternoon on the Amazon Osborne, Mary Pope 2.6 1.0 119440 EN Airman Colfer, Eoin 5.8 16.0 5051 EN Alan and Naomi Levoy, Myron 3.3 5.0 19738 EN Alaskan Adventure, The Dixon, Franklin W. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------- ------ 12 Again Sue Corbett 4.9 8 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5 9 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Tim Cooke 6.1 1 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10 28 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M. Deem 3.6 5 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9 47 Walter Mosley 5.3 8 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9 Abandoned Puppy Emily Costello 4.1 3 Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15 Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6 The Abduction Mette Newth 6 8 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16 Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary W Jacqueline Ching 8.1 2 About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9 Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7 Abraham Lincoln: Friend of the P Clara Ingram Judso 7.3 7 N Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to E.B. Phillips 8 4 N Absolute Brightness James Lecesne 6.5 15 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 N The Absolutely True Diary of a P Sherman Alexie 4 6 N An Abundance of Katherines John Green 5.6 10 Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7 An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11 N Accidental Love Gary Soto 4.8 5 Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4 The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2 Acorna: The Unicorn Girl -

October, 2011 Title Author RL Points 42509 Genetics: Unlocking The

October, 2011 Title Author RL points 42509 Genetics: unlocking the secrets of life Aaseng, Nathan 9.9 4.0 57540 Track and field (History of sports) Aaseng, Nathan 10.1 5.0 11844 True champions Aaseng, Nathan 7.5 5.0 21609 Go and come back Abelove, Joan 3.8 5.0 75505 Tobey Maguire Abraham, Philip 5.5 1.0 86936 Down the Rabbit Hole Abrahams, Peter 4.3 10.0 130987 Reality check Abrahams, Peter 4.6 9.0 69874 Cystic Fibrosis Abramovitz, Melissa 11.8 4.0 107829 Lou Gehrig's Disease Abramovitz, Melissa 10.9 4.0 69873 Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Abrams, Liesa 11.9 4.0 106418 Defining Dulcie Acampora, Paul 4.0 4.0 79634 Things fall apart Achebe, Chinua 6.2 8.0 29326 Thunder ice Acheson, Alison 4.9 5.0 6048 Leaves in October, The Ackerman, Karen 5.4 3.0 54122 Life, the Universe and everything Adams, Douglas 7.6 9.0 18830 Restaurant at the end of the Universe, The Adams, Douglas 6.1 8.0 54127 So long, and thanks for all the fish Adams, Douglas 6.9 7.0 7109 Hitchhiker's guide to the galaxy Adams, Douglas 6.6 8.0 749 Watership down Adams, Richard 6.2 25.0 731 Born free Adamson, Joy 7.3 9.0 17764 Courtyard cat Adler, C.S. 4.6 5.0 5014 Ghost brother Adler, C.S. 4.2 5.0 480 Magic of the Glits Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 5965 Tuna fish Thanksgiving Adler, C.S. -

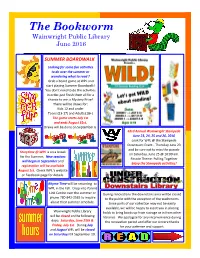

The Bookworm Wainwright Public Library June 2016

The Bookworm Wainwright Public Library June 2016 SUMMER BOARDWALK Looking for some fun activities to do over the summer or wondering what to read ? Grab a board game at WPL and start playing Summer Boardwalk! You don’t need to do the activities in order-just finish them all for a chance to win a Mystery Prize! There will be draws for: Kids 12 and under Teens (13-17) and Adults (18+) The game starts July 1st and ends August 31st. Draws will be done on September 6. 63rd Annual Wainwright Stampede June 23, 24, 25 and 26, 2016 Look for WPL @ the Stampede Downtown Event - Thursday June 23 and be sure not to miss the parade Storytime @ WPLis on a break on Saturday, June 25 @ 10:00 am. for the Summer. New sessions Parade Theme: Pulling Together will begin in September and Enjoy the Stampede activities! registration will be available August 1st. Check WPL’s website or Facebook page for details. Rhyme Time will be returning to WPL in the Fall. Drop into Parent Link Centre over the summer or During renovations the downstairs area will be closed phone 780-842-2585 to inquire to the public with the exception of the washrooms. about their summer schedule. Since parts of our collection may not be easily available, we will be happy to assist you in placing Wainwright Public Library holds to bring books up from storage or in from other will be closed on the following libraries. We apologize for any inconvenience during days: Saturday, June 25th & the renovation period and offer our sincere thanks Friday, July 1st. -

Advocacy Issue

THE ADVOCACY ISSUE THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE YOUNG ADULT LIBRARY SERVICES ASSOCIATION VOLUME NUMBER 15 03 CYPHER AS YOUTH ADVOCACY SPRING 2017 LIBRARIES AS REFUGE FOR ADVOCATING FOR CREATING A UNIQUE MARGINALIZED YOUTH TEENS IN PUBLIC BRAND FOR YOUR $17.50 » ISSN 1541-4302 LIBRARIES + SCHOOL LIBRARY registration now open! YALSA’SYALSA’SYoungYoung AdultAdult ServicesServices Louisville,Louisville, KYKY •• NovemberNovember 3–5,3–5, 20172017 # YA LS A17 JOIn us as we explore ways to empower teens to increase your library’s impact! The Official Journal of the Young Adult Library Services Association SPRING 2017 VOLUME 15 | NUMBER 3 CONTENTS ISSN 1541-4302 HIGHLIGHT FEATURES 4 25 YALSA’S SELECTED LISTS, 2.0 ADVOCATING FOR TEENS IN PUBLIC LIBRARIES+ 6 » Tiffany Boeglen & Britni Cherrington-Stoddart THE LIBRARY’S ROLE IN PROTECTING TEENS’ PRIVACY: 31 A YALSA POSITION PAPER CREATING A UNIQUE BRAND FOR YOUR SCHOOL LIBRARY 8 » Kelsey Barker ANSWERING THE CALL FOR MIDDLE SCHOOL COLLEGE 36 AND CAREER READINESS: YALSA “FUTURE READY” LIBRARIES AS REFUGE FOR MARGINALIZED YOUTH PROJECT KICKS OFF » Deborah Takahashi » Laura Pitts 40 10 FROM AWARENESS TO ADVOCACY: AN URBAN TEEN REIMAGINED LIBRARY SERVICES FOR AND WITH TEENS LIBRARIAN’S JOURNEY FROM PASSIVITY TO ACTIVISM 11 » David Wang 2017 YALSA BOOK AWARD WINNERS AND SELECTED 43 BOOK AND MEDIA LISTS MAKING A CASE FOR TEENS SERVICES: TRANSFORMING LIBRARIES AND PUBLISHING » Audrey Hopkins EXPLORE 15 RESEARCH ROUNDUP: ADVOCACY: A FOCUS ON PRIVACY PLUS AND SURVEILLANCE » Lucia Cedeira Serantes 2 45 FROM THE EDITOR GUIDELINES FOR AUTHORS » Crystle Martin INDEX TO ADVERTISERS 3 46 TRENDING FROM THE PRESIDENT THE YALSA UPDATE 18 » Sarah Hill USING MEDIA LITERACY TO COMBAT YOUTH EXTREMISM » D.C. -

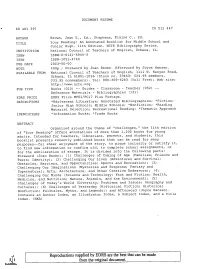

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document. Your Pca an Annotated Booklist for Middle &Hod

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 481 397 CS 512 447 AUTHOR Brown, Jean E., Ed.; Stephens, Elaine C., Ed. TITLE Your Reading: An Annotated Booklist for Middle School and Junior High. llth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5944-3 ISSN ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 400p.; Foreword by Joan Bauer. Afterword by Joyce Hansen. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 59443: $24.95 members, $33.95 nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Fiction; Junior High Schools; Middle Schools; *Nonfiction; *Reading Material Selection; Recreational Reading; *Thematic Approach IDENTIFIERS *Information Books; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Organized around the theme of "challenges," the llth edition of "Your Reading" offers annotations of more than 1,200 books for young adults. Intended for teachers, librarians, parents, and students, this booklist presents recently published books that can be read for many purposes--for sheer enjoyment of the story, to pique curiosity orsatisfy it, to find new information or confirm old, to completeschool assignments, or for the exhilaration of escape. It is divided into thefollowing parts: Foreword (Joan Bauer);(1) Challenges of Coming of Age (Families; -

Free Keeping the Moon Pdf

FREE KEEPING THE MOON PDF Sarah Dessen | 228 pages | 19 Jul 2011 | Penguin Young Readers Group | 9780142401767 | English | New York, NY, United States Keeping the Moon read online free by Sarah Dessen Dessen Someone Like You,etc. Paulsen Keeping the Moon personal experiences that he incorporated into Hatchet and its three sequels, from savage attacks by moose and mosquitoes to watching helplessly as a heart-attack victim dies. The author adds incidents from his Iditarod races, describes how he made, then learned to hunt with, bow and Keeping the Moon, then closes with methods of cooking outdoors sans pots or pans. Well-meaning but far too accustomed to getting her way, Aunt Patty buys the children unwanted new clothes, enrolls them in a Bible day camp for one Keeping the Moon day, and even tries to line up friends for them. While politely tolerating her hovering, the two inseparable sisters find their own path, hooking up with a fearless, wonderfully plainspoken teenaged neighbor and her dirt-loving brothers, Keeping the Moon, acting on an obscure but ultimately healing impulse, climbing out onto the roof to get a bit closer to Heaven, and Baby. Lightening the tone by poking gentle fun at Patty and some of her small-town neighbors, the author creates a cast founded on likable, real-seeming people who grow and change in response to tragedy. Already have an account? Log in. Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials. Sign Up. Pub Date: Sept. Page Count: Publisher: Viking. No Comments Yet. More by Sarah Dessen. Pub Date: Feb. Page Count: Publisher: Delacorte. -

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 5550 Why Mosquitoes Buzz...Ears Aardema, Verna 3.2 0.5 EN 5365 Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nate 6.9 3.0 EN 5366 Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nate 6.9 3.0 EN 6713 David Robinson Aaseng, Nathan 6.2 2.0 EN 8467 Florence Griffith Joyner Aaseng, Nathan 7.2 2.0 EN 6739 Michael Jordan Aaseng, Nathan 6.5 2.0 EN 8480 Navajo Code Talkers Aaseng, Nathan 8.7 5.0 EN 8289 Sports Great Kirby Puckett Aaseng, Nathan 6.4 2.0 EN 35264 Saying It Out Loud Abelove, Joan 3.5 4.0 EN Why the Tortoise's Shell Is Not 971 EN Achebe, Chinua 1.0 1.0 Smooth (Short Story) 6048 Leaves in October, The Ackerman, Karen 5.0 3.0 EN 5490 Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 3.8 0.5 EN 7109 Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Adams, Douglas 8.3 11.0 EN The 1004 Restaurant at the end of the Adams, Douglas 6.1 8.0 EN Universe, The 749 EN Watership Down Adams, Richard 7.6 32.0 731 EN Born Free Adamson, Joy 7.8 9.0 5414 Eddie's Blue-Winged Dragon Adler, C.S. 5.2 3.0 EN 5014 Ghost Brother Adler, C.S. 5.8 4.0 EN 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 2.0 5965 Tuna Fish Thanksgiving Adler, C.S. 5.7 7.0 EN 5210 Cam Jansen...Monkey House Adler, David A. -

The Sarah Dessen Book Club Kit

THE SARAH DESSEN BOOK CLUB KIT SPEND YOUR SUMMER WITH SARAH Dear Book Club Coordinator: Here at Penguin Young Readers Group we are calling Summer 2013 The Summer of Sarah. The beloved bestseller Sarah Dessen will be publishing her 11th book this summer, which takes place in one of her fans’ favorite settings, the fi ctional beach town of Colby. Dessen’s latest novel, The Moon and More, will be hitting the shelves this June, and she will be touring in schools and bookstores all across the country to connect with her fans new and old. In anticipation of a local visit, or in lieu of meeting the author in person, we have assembled your Summer of Sarah book club kit to welcome readers in your community into your local book club meetings all summer long. With Penguin's Summer of Sarah book club kit, you can hold discussions about specifi c Dessen titles or more thematic sessions on a variety of topics, such as relationships, moving away, loss and letting go, and change (which everyone can relate to). Since the summer is time for teens to let go of the worries and stress of the school “ year, this book club kit also includes fun quizzes, a recipe from Sarah's favorite summer treats, and playlists handpicked by Sarah herself. Tailor your book club in whatever format best fi ts your participants, and have a fun-fi lled summer… with Sarah! 1 stick margarine Tips for your event: 1.5 graham cracker crumbs 1 small bag chocolate chips 14 oz.