Early Large Borings in a Hardground of Floian-Dapingian Age (Early and Middle Ordovician) in Northeastern Estonia (Baltica)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Change and the Selective Signature of the Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

Climate change and the selective signature of the Late Ordovician mass extinction Seth Finnegana,b,1, Noel A. Heimc, Shanan E. Petersc, and Woodward W. Fischera aDivision of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91125; bDepartment of Integrative Biology, University of California, 1005 Valley Life Sciences Bldg #3140, Berkeley, CA 94720; and cDepartment of Geoscience, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1215 West Dayton Street, Madison, WI 53706 Edited by Richard K. Bambach, Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., and accepted by the Editorial Board March 6, 2012 (received for review October 14, 2011) Selectivity patterns provide insights into the causes of ancient ex- sedimentary record (common cause hypothesis) (14). For the tinction events. The Late Ordovician mass extinction was related LOME, it is useful to split common cause into two hypotheses. to Gondwanan glaciation; however, it is still unclear whether ele- The eustatic common cause hypothesis postulates that Gondwa- vated extinction rates were attributable to record failure, habitat nan glaciation drove the extinction by lowering eustatic sea level, loss, or climatic cooling. We examined Middle Ordovician-Early thereby reducing the overall area of shallow marine habitats, Silurian North American fossil occurrences within a spatiotempo- reorganizing habitat mosaics, and disrupting larval dispersal cor- rally explicit stratigraphic framework that allowed us to quantify ridors (16–18). The climatic common cause hypothesis postulates rock record effects on a per-taxon basis and assay the interplay of that climate cooling, in addition to being ultimately responsible macrostratigraphic and macroecological variables in determining for sea-level drawdown and attendant habitat losses, had a direct extinction risk. -

Trilobites of the Hagastrand Member (Tøyen Formation, Lowermost Arenig) from the Oslo Region, Norway. Part Il: Remaining Non-Asaphid Groups

Trilobites of the Hagastrand Member (Tøyen Formation, lowermost Arenig) from the Oslo Region, Norway. Part Il: Remaining non-asaphid groups OLE A. HOEL Hoel, O. A.: Trilobites of the Hagastrand Member (Tøyen Formation, lowermost Arenig) from the Oslo Region, Norway. Part Il: remaining non-asaphid groups. Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift, Vol. 79, pp. 259-280. Oslo 1999. ISSN 0029-196X. This is Part Il of a two-part description of the trilobite fauna of the Hagastrand Member (Tøyen Formation) in the Oslo, Eiker Sandsvær, Modum and Mjøsa areas. In this part, the non-asaphid trilobites are described, while the asaphid species have been described previously. The history and status of the Tremadoc-Arenig Boundary problem is also reviewed, and I have found no reason to insert a Hunnebergian Series between the Tremadoc and the Arenig series, as has been suggested by some workers. Descriptions of the localities yielding this special trilobite fauna are provided. Most of the 22 trilobite species found in the Hagastrand Member also occur in Sweden. The 12 non-asaphid trilobites described herein belong to the families Metagnostidae, Shumardiidae, Remopleurididae, Nileidae, Cyclopygidae, Raphiophoridae, Alsataspididae and Pliomeridae. One new species is described; Robergiella tjemviki n. sp. Ole A. Hoel, Paleontologisk Museum, Sars gate l, N-0562 Oslo, Norway. Introduction contemporaneous platform deposits in Sweden are domi nated by a condensed limestone succession. In Norway, the The Tremadoc-Arenig Boundary interval is a crucial point Tøyen Formation is divided into two members: the lower in the evolution of several invertebrate groups, especially among the graptolites and the trilobites. In the graptolites, this change consisted most significantly in the loss of bithekae and a strong increase in diversity. -

Trace Fossils from the Baltoscandian Erratic Boulders in Sw Poland

Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae (2017), vol. 87: 229–257 doi: https://doi.org/10.14241/asgp.2017.014 TRACE FOSSILS FROM THE BALTOSCANDIAN ERRATIC BOULDERS IN SW POLAND Alina CHRZĄSTEK & Kamil PLUTA Institute of Geological Sciences, Wrocław University; Maksa Borna 9, 50-204 Wrocław, Poland e-mails: [email protected], [email protected] Chrząstek, A. & Pluta, K, 2017. Trace fossils from the Baltoscandian erratic boulders in SW Poland. Annales Societatis Geologorum Poloniae, 87: 229–257. Abstract: Many well preserved trace fossils were found in erratic boulders and the fossils preserved in them, occurring in the Pleistocene glacial deposits of the Fore-Sudetic Block (Mokrzeszów Quarry, Świebodzice outcrop). They include burrows (Arachnostega gastrochaenae, Balanoglossites isp., ?Balanoglossites isp., ?Chondrites isp., Diplocraterion isp., Phycodes isp., Planolites isp., ?Rosselia isp., Skolithos linearis, Thalassinoides isp., root traces) and borings ?Gastrochaenolites isp., Maeandropolydora isp., Oichnus isp., Osprioneides kamp- to, ?Palaeosabella isp., Talpina isp., Teredolites isp., Trypanites weisei, Trypanites isp., ?Trypanites isp., and an unidentified polychaete boring in corals. The boulders, Cambrian to Neogene (Miocene) in age, mainly came from Scandinavia and the Baltic region. The majority of the trace fossils come from the Ordovician Orthoceratite Limestone, which is exposed mainly in southern and central Sweden, western Russia and Estonia, and also in Norway (Oslo Region). The most interesting discovery in these deposits is the occurrence of Arachnostega gastrochaenae in the Ordovician trilobites (?Megistaspis sp. and Asaphus sp.), cephalopods and hyolithids. This is the first report ofArachnostega on a trilobite (?Megistaspis) from Sweden. So far, this ichnotaxon was described on trilobites from Baltoscandia only from the St. -

Available Generic Names for Trilobites

AVAILABLE GENERIC NAMES FOR TRILOBITES P.A. JELL AND J.M. ADRAIN Jell, P.A. & Adrain, J.M. 30 8 2002: Available generic names for trilobites. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 48(2): 331-553. Brisbane. ISSN0079-8835. Aconsolidated list of available generic names introduced since the beginning of the binomial nomenclature system for trilobites is presented for the first time. Each entry is accompanied by the author and date of availability, by the name of the type species, by a lithostratigraphic or biostratigraphic and geographic reference for the type species, by a family assignment and by an age indication of the type species at the Period level (e.g. MCAM, LDEV). A second listing of these names is taxonomically arranged in families with the families listed alphabetically, higher level classification being outside the scope of this work. We also provide a list of names that have apparently been applied to trilobites but which remain nomina nuda within the ICZN definition. Peter A. Jell, Queensland Museum, PO Box 3300, South Brisbane, Queensland 4101, Australia; Jonathan M. Adrain, Department of Geoscience, 121 Trowbridge Hall, Univ- ersity of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242, USA; 1 August 2002. p Trilobites, generic names, checklist. Trilobite fossils attracted the attention of could find. This list was copied on an early spirit humans in different parts of the world from the stencil machine to some 20 or more trilobite very beginning, probably even prehistoric times. workers around the world, principally those who In the 1700s various European natural historians would author the 1959 Treatise edition. Weller began systematic study of living and fossil also drew on this compilation for his Presidential organisms including trilobites. -

Polar Front Shift and Atmospheric CO During the Glacial Maximum of the Early Paleozoic Icehouse

Polar front shift and atmospheric CO2 during the glacial maximum of the Early Paleozoic Icehouse Thijs R. A. Vandenbrouckea,b,c,1,2, Howard A. Armstronga,1, Mark Williamsd,e,1, Florentin Parisf, Jan A. Zalasiewiczd, Koen Sabbeg, Jaak Nõlvakh, Thomas J. Challandsa,i, Jacques Verniersb, and Thomas Servaisc aPalaeoClimate Group, Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University, Science Labs, Durham, DH1 3LE, United Kingdom; bResearch Unit Palaeontology, Department of Geology, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281-S8, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; cGéosystèmes, Université Lille 1, Formation de Recherche en Evolution 3298 du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Avenue Paul Langevin, bâtiment SN5, 59655 Villeneuve d’Ascq Cedex, France; dDepartment of Geology, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH, United Kingdom; eBritish Geological Survey, Kingsley Dunham Centre, Keyworth, NG12 5GG, United Kingdom; fGéosciences, Université de Rennes I, Unité Mixte de Recherche 6118 du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Campus de Beaulieu, 35042 Rennes-cedex, France; gProtistology and Aquatic Ecology, Department of Biology, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281-S8, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; hInstitute of Geology, Tallinn University of Technology, Ehitajate tee 5, 19086 Tallinn, Estonia; and iTotal E&P UK Limited, Geoscience Research Centre, Crawpeel Road, Aberdeen AB12 3FG, United Kingdom Edited by Jeffrey Kiehl, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO, and accepted by the Editorial Board July 1, 2010 (received for review March 16, 2010) Our new data address the paradox of Late Ordovician glaciation PAL (5). A GCM experiment parameterized with the same p × under supposedly high CO2 (8 to 22 PAL: preindustrial atmo- pCO2 value, high relative sea level, and a modern equator-to-pole spheric level). -

Trilobite Fauna of the Šárka Formation at Praha – Červený Vrch Hill (Ordovician, Barrandian Area, Czech Republic)

Bulletin of Geosciences, Vol. 78, No. 2, 113–117, 2003 © Czech Geological Survey, ISSN 1214-1119 Trilobite fauna of the Šárka Formation at Praha – Červený vrch Hill (Ordovician, Barrandian area, Czech Republic) PETR BUDIL 1 – OLDŘICH FATKA 2 – JANA BRUTHANSOVÁ 3 1 Czech Geological Survey, Klárov 3, 118 21 Praha 1, Czech Republic. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Charles University, Faculty of Science, Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Albertov 6, 128 43 Praha 2, Czech Republic. E-mail: [email protected] 3 National Museum, Palaeontological Department, Václavské nám. 68, 115 79 Praha 1, Czech Republic. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Shales of the Šárka Formation exposed in the excavation on Červený vrch Hill at Praha-Vokovice contain a common but monotonous assem- blage of phyllocarids associated with other extremely rare arthropods. Almost all trilobite remains (genera Ectillaenus Salter, 1867, Placoparia Hawle et Corda, 1847 and Asaphidae indet.) occur in a single horizon of siliceous nodules of stratigraphically uncertain position, while the surprising occurrence of possible naraoid trilobite (Pseudonaraoia hammanni gen. n., sp. n.) comes from dark grey shales. The general character of the arthropod assemblage char- acterized by an expressive dominance of planktonic and/or epi-planktonic elements (phyllocarids) indicates a specific life environment (most probably due to poor oxygenation). This association corresponds to the assemblage preceding the Euorthisina-Placoparia Community sensu Havlíček and Vaněk (1990) in the lower portion of the Šárka Formation. Key words: Ordovician, Arthropoda, Trilobita, Naraoiidae, Barrandian Introduction calities, the trilobite remains on Červený vrch Hill occur in siliceous nodules in association with rare finds of car- The temporary exposure at the Praha-Červený vrch Hill poids (Lagynocystites a.o.), frequent remains of phyllo- provided a unique possibility to study a well-exposed secti- carids (Caryocaris subula Chlupáč, 1970 and C. -

Megistaspis Gibba from the Area of Mining Works in Mielenko Drawskie, the Drawskie Lake- Land, Poland

4 Megistaspis gibba from the Area of Mining Works in Mielenko Drawskie, the Drawskie Lake- land, Poland Tomasz Borowski University of Szczecin 1. Introduction The area of mining works in Mielenko Drawskie in the Drawskie Lake- land, Western Pomeranian Province, is a typical post-glacial site. However, marine sedimentary limestones of Swedish origin can be found here. These limestone rocks are characterised first of all by a large content of ferric oxide (III) (Fe2O3). Fossilised arthropods (Arthropoda) can be observed in them, in particular trilobites (Trilobita). It can be stated that the largest and most fre- quently encountered here trilobites of the Megistaspis genus are Megistaspis gibba. However, no complete specimens of these trilobites have been observed so far. In the territory of Poland, about 170 species within the group of Ordo- vician trilobites, belonging to 84 genera and represented by 36 families, have been known. Twenty one species are Polish holotypes. The Ordovician trilo- bites have not been examined to the same extent. The Upper Ordovician trilo- bites have been elaborated the best. About 80 species, belonging to 40 genera, have been found. The expansion of trilobites depends on the distribution of lithofacies within the Ordovician sedimentation basin. In limestone and marl lithofacies, trilobites are found accompanied by most abundant brachiopods, cephalopods, ostracods and echinoderms. Trilobites are found abundantly together with brachiopods in light, limestone clayey-mud sediments of the Upper Ordovician period in the Świę- tokrzyskie Mountains. Trilobites are of fundamental importance when elaborat- ing the biostratigraphy of Ordovician sediments, in particular those developed on carbonate, marl and mud lithofacies. -

The Ordovician Succession Adjacent to Hinlopenstretet, Ny Friesland, Spitsbergen

1 2 The Ordovician succession adjacent to Hinlopenstretet, Ny Friesland, Spitsbergen 3 4 Björn Kröger1, Seth Finnegan2, Franziska Franeck3, Melanie J. Hopkins4 5 6 Abstract: The Ordovician sections along the western shore of the Hinlopen Strait, Ny 7 Friesland, were discovered in the late 1960s and since then prompted numerous 8 paleontological publications; several of them are now classical for the paleontology of 9 Ordovician trilobites, and Ordovician paleogeography and stratigraphy. Our 2016 expedition 10 aimed in a major recollection and reappraisal of the classical sites. Here we provide a first 11 high-resolution lithological description of the Kirtonryggen and Valhallfonna formations 12 (Tremadocian –Darriwilian), which together comprise a thickness of 843 m, a revised bio-, 13 and lithostratigraphy, and an interpretation of the depositional sequences. We find that the 14 sedimentary succession is very similar to successions of eastern Laurentia; its Tremadocian 15 and early Floian part is composed of predominantly peritidal dolostones and limestones 16 characterized by ribbon carbonates, intraclastic conglomerates, microbial laminites, and 17 stromatolites, and its late Floian to Darriwilian part is composed of fossil-rich, bioturbated, 18 cherty mud-wackestone, skeletal grainstone and shale, with local siltstone and glauconitic 19 horizons. The succession can be subdivided into five third-order depositional sequences, 20 which are interpreted as representing the SAUK IIIB Supersequence known from elsewhere 21 on the Laurentian -

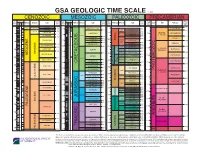

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

(Floian) Conodont Fauna from the Eastern Cordillera of Peru (Central Andean Basin) Geologica Acta: an International Earth Science Journal, Vol

Geologica Acta: an international earth science journal ISSN: 1695-6133 [email protected] Universitat de Barcelona España GUTIÉRREZ-MARCO, J.C.; ALBANESI, G.L.; SARMIENTO, G.N.; CARLOTTO, V. An Early Ordovician (Floian) Conodont Fauna from the Eastern Cordillera of Peru (Central Andean Basin) Geologica Acta: an international earth science journal, vol. 6, núm. 2, junio, 2008, pp. 147-160 Universitat de Barcelona Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=50513115004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Geologica Acta, Vol.6, Nº 2, June 2008, 147-160 DOI: 10.1344/105.000000248 Available online at www.geologica-acta.com An Early Ordovician (Floian) Conodont Fauna from the Eastern Cordillera of Peru (Central Andean Basin) 1 2 1 3,4 J.C. GUTIÉRREZ-MARCO G.L. ALBANESI G.N. SARMIENTO and V. CARLOTTO 1 Instituto de Geología Económica (CSIC-UCM). Facultad de Ciencias Geológicas 28040 Madrid, Spain. Gutiérrez-Marco E-mail: [email protected] Sarmiento E-mail: [email protected] 2 CONICET-CICTERRA, Museo de Paleontología Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba Casilla de Correo 1598, 5000 Córdoba, Argentina. E-mail: [email protected] 3 INGEMMET Avenida Canadá 1740, San Borja, Lima, Peru. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Departamento de Geología, Universidad Nacional San Antonio Abad del Cusco Avda. de la Cultura 733, Cuzco, Perú ABSTRACT Late Floian conodonts are recorded from a thin limestone lens intercalated in the lower part of the San José For- mation at the Carcel Puncco section (Inambari River), Eastern Cordillera of Peru. -

International Chronostratigraphic Chart

INTERNATIONAL CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC CHART www.stratigraphy.org International Commission on Stratigraphy v 2018/08 numerical numerical numerical Eonothem numerical Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age GSSP GSSP GSSP GSSP EonothemErathem / Eon System / Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) / Eon Erathem / Era System / Period GSSA age (Ma) present ~ 145.0 358.9 ± 0.4 541.0 ±1.0 U/L Meghalayan 0.0042 Holocene M Northgrippian 0.0082 Tithonian Ediacaran L/E Greenlandian 152.1 ±0.9 ~ 635 Upper 0.0117 Famennian Neo- 0.126 Upper Kimmeridgian Cryogenian Middle 157.3 ±1.0 Upper proterozoic ~ 720 Pleistocene 0.781 372.2 ±1.6 Calabrian Oxfordian Tonian 1.80 163.5 ±1.0 Frasnian Callovian 1000 Quaternary Gelasian 166.1 ±1.2 2.58 Bathonian 382.7 ±1.6 Stenian Middle 168.3 ±1.3 Piacenzian Bajocian 170.3 ±1.4 Givetian 1200 Pliocene 3.600 Middle 387.7 ±0.8 Meso- Zanclean Aalenian proterozoic Ectasian 5.333 174.1 ±1.0 Eifelian 1400 Messinian Jurassic 393.3 ±1.2 7.246 Toarcian Devonian Calymmian Tortonian 182.7 ±0.7 Emsian 1600 11.63 Pliensbachian Statherian Lower 407.6 ±2.6 Serravallian 13.82 190.8 ±1.0 Lower 1800 Miocene Pragian 410.8 ±2.8 Proterozoic Neogene Sinemurian Langhian 15.97 Orosirian 199.3 ±0.3 Lochkovian Paleo- 2050 Burdigalian Hettangian 201.3 ±0.2 419.2 ±3.2 proterozoic 20.44 Mesozoic Rhaetian Pridoli Rhyacian Aquitanian 423.0 ±2.3 23.03 ~ 208.5 Ludfordian 2300 Cenozoic Chattian Ludlow 425.6 ±0.9 Siderian 27.82 Gorstian -

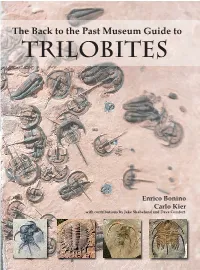

Th TRILO the Back to the Past Museum Guide to TRILO BITES

With regard to human interest in fossils, trilobites may rank second only to dinosaurs. Having studied trilobites most of my life, the English version of The Back to the Past Museum Guide to TRILOBITES by Enrico Bonino and Carlo Kier is a pleasant treat. I am captivated by the abundant color images of more than 600 diverse species of trilobites, mostly from the authors’ own collections. Carlo Kier The Back to the Past Museum Guide to Specimens amply represent famous trilobite localities around the world and typify forms from most of the Enrico Bonino Enrico 250-million-year history of trilobites. Numerous specimens are masterpieces of modern professional preparation. Richard A. Robison Professor Emeritus University of Kansas TRILOBITES Enrico Bonino was born in the Province of Bergamo in 1966 and received his degree in Geology from the Depart- ment of Earth Sciences at the University of Genoa. He currently lives in Belgium where he works as a cartographer specialized in the use of satellite imaging and geographic information systems (GIS). His proficiency in the use of digital-image processing, a healthy dose of artistic talent, and a good knowledge of desktop publishing software have provided him with the skills he needed to create graphics, including dozens of posters and illustrations, for all of the displays at the Back to the Past Museum in Cancún. In addition to his passion for trilobites, Enrico is particularly inter- TRILOBITES ested in the life forms that developed during the Precambrian. Carlo Kier was born in Milan in 1961. He holds a degree in law and is currently the director of the Azul Hotel chain.