Global Report on Human Settlements 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1990

National Endowment For The Arts Annual Report National Endowment For The Arts 1990 Annual Report National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1990. Respectfully, Jc Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. April 1991 CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement ............................................................5 The Agency and its Functions .............................................29 . The National Council on the Arts ........................................30 Programs Dance ........................................................................................ 32 Design Arts .............................................................................. 53 Expansion Arts .....................................................................66 ... Folk Arts .................................................................................. 92 Inter-Arts ..................................................................................103. Literature ..............................................................................121 .... Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ..................................137 .. Museum ................................................................................155 .... Music ....................................................................................186 .... 236 ~O~eera-Musicalater ................................................................................ -

From Urban Renewal to Affordable Housing Production System: Boston Mayors and the Evolution of Community Development Corporations in Boston

From Urban Renewal to Affordable Housing Production System: Boston Mayors and the Evolution of Community Development Corporations in Boston April 2016 Published by The Community Innovators Lab (CoLab) MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) Karl Seidman, Senior Lecturer in Economic Development ([email protected]) Tunney Lee, Professor Emeritus ([email protected]) Elise Selinger, Master in City Planning 2016 ([email protected]) White Paper Organization 1. Introduction 2. Building a “New Boston” and Urban Renewal Mayor Hynes (1950 -1959) 3. From Mass Clearance to “Planning with People” Mayor Collins (1960 -1967) 4. The Emergence of Boston’s Early CDCs Mayor White I (1968 -1975) 5. The Growth of Boston CDCs Mayor White II (1976 -1983) 6. Maturing State and Local Support Mayor Flynn (1984 -1993) 7. An Ecosystem of Interdependence Mayor Menino (1994 -2013) 8. Conclusion 1 1. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate how a uniquely robust ecosystem of support for Community Development Corporations (CDCs) in Boston has grown over time to make Boston a preeminent city for CDC housing production in the country. A CDC is defined as “a nonprofit, community-based development organization that engages in community development activities such as housing production, commercial property development, business development, social services and/or job creation for the benefit of community residents.”1 Boston has been a leader, first in utilizing the federal programs and later in designing and implementing creative local initiatives for affordable housing production.2 Boston’s urban renewal program resulted significant community displacement but there was also land for mayors to allocate to CDCs for the development of permanent affordable housing. -

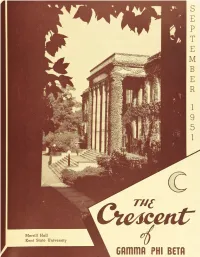

September^ 1951 Where Beta Zeta Chapter Oj Gamma Phi Beta Was Chartered October 2^, It)4'J

:�>. ' VI ^^g . -^^W! .?^^�Kl '^^^^� ,1?^'^ 1^ T-Z/if (jie^cciit Merrill Hall Kent State University Gflmmfl PHI BCTfl Gamma Phi Beta from the past has given A heritage that makes a fuller life. Gamma Phi Beta in the present bids Us Strive for lasting values and ideals. Gamma Phi Beta in the days to come Will prove that fundamentals can endure. Therefore we shall embody in our lives The truths that make for finer womanhood. Once more we pledge a loyalty that means Adherence to all true and noble things; A learning that enriches all our days With magic gold that is forever ours ; A labor that each hour will glorify The simple, common task, the common cause; A love that will be strong and great enough To compass and to pity all the world. cJ~oue, czd-abor, cj~.earnlna, cJLotAaltiA � \Jur L^reed I ivill try this day to live a simple, sincere and serene life, re pelling promptly every thought of discontent, anxiety, dis couragement, impurity, self-seeking; cultivating cheerfulness, magnanimity, charity and the habit of holy silence; exercising economy in expenditure, generosity in giving, carefulness in conversation, diligence in appointed service, fidelity to every trust and a childlike faith in God. The Crescent of Gamma Phi Beta Voluine LI; Number 3 The Cover Contents four Merrill Hall, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio, September^ 1951 where Beta Zeta chapter oj Gamma Phi Beta was chartered October 2^, it)4'j. Meet the Presidents! Frontispiece 2 The Crescent is published September 15, Decem Kent State University . Young and Growing Fast! 3 ber 1, March 15, and May 1, by the George Banta Publishing Company, official printers of the Portraits for Phi Delta Theta 4 fraternity, at 450 Ahnaip Street, Menasha, Wiscon sin. -

Architecture Program Report for 2011 NAAB Visit for Continuing Accreditation

University of Maryland School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation Architecture Program Report for 2011 NAAB Visit for Continuing Accreditation Master of Architecture Degree [degree + 109] Master of Architecture Degree [pre-professional degree + 60] Year of the Previous Visit: 2005 Current Term of Accreditation: six year term Submitted to: The National Architectural Accrediting Board Date: 7 September 2010 Rev: 11 February 2011 University of Maryland Architecture Program Report September 2010, revised February 2011 Name and contact information for the following: Program Administrator: Madlen Simon AIA, [email protected] 301-405-8000 (main) 202-330-2912 (mobile) Chief administrator for the academic unit in which the program is located: David Cronrath AIA, [email protected] 201-405-8000 Chief Academic Officer of the Institution: Dr. Nariman Farvardin [email protected] 301-405-1603 (until February 28, 2011); Dr. Ann G. Wylie [email protected] 301-405-6400 (after March 1, 2011) President of the Institution: Dr. Wallace Loh [email protected] 301-405-5803 Individual submitting the Architecture Program Report: Madlen Simon AIA Name of individual to whom questions should be directed: Madlen Simon AIA iii University of Maryland Architecture Program Report September 2010, revised February 2011 Table of Contents Section Page Part One. Institutional Support and Commitment to Continuous Improvement 1 1. Identify & Self Assessment 1 1. History Mission 1 2. Learning Culture and Social Equity 8 3. Responses to the Five Perspectives 14 4. Long Range Planning 23 5. Program Self Assessment 27 2. Resources 34 1. Human Resources and Human Resource Development 34 2. Administrative Structure and Governance 57 3. -

Journal of Architectural Education Fall Editorial Board Meeting Portland

Journal of Architectural Education Fall Editorial Board Meeting Portland State University Portland, OR 02-04 October 2015 Table of Contents General Information . 1 Meeting Schedule . 2 Meeting Agenda . 3 Reports Executive Editor . .. 4 Associate Editor, Design . 5 Associate Editor, Reviews . 6 Art Director . 8 Additional Material Spring 2015 Board Meeting Minutes Theme Issue Proposals Essays to be considered for the JAE Awards General Information Welcome to the Journal of Architectural Education 2015 Fall Editorial Board Meeting. All of our meetings will occur at Portland State University (1825 SW Broadway, Portland, OR 97201) If you are unable to attend the meeting, a skype connection can be provided. Please email Marc Neveu ([email protected]) if you wish to participate via skype. While in Portland, Marc Neveu may be reached by phone at: 617-899-6965. Barton Residence: (1920 SW River Drive, E101) 1 Meeting Schedule Friday, 02 October 4.00 pm Clive Knights to introduce Editorial Board to students Shattuck Hall, 1914 SW Broadway 4.15 pm Tour, School of Architecture 5.00 pm Happy Hour at Professor Emeritus Rudy Barton's house 1920 SW River Drive, E101 Saturday, 03 October 9.00 – 12.30 Design Committee Meeting Shattuck Hall, 1914 SW Broadway: Room 250 Kulper, Fujita, Jackson, La, Sprecher, Stuth, Squire, Theodore 9.00 – 12.30 Reviews Committee Meeting Shattuck Hall, 1914 SW Broadway: Room 235 Rupnik, Contandriopoulos, Mumford, Nawre, Trubiano, Wendl 9.00 – 12.30 70:1 Shattuck Hall, 1914 SW Broadway: Office pod Neveu, Brennan, Weddle 1.30 – 5.00 Editorial Board Meeting Shattuck Hall, 1914 SW Broadway: Room 210 Full Editorial Board, Monti, Reimers, Vonier 7.00 Andina 1314 NW Glisan St. -

Making the Woods Hole Dome: the Story of R

Falmouth Historical Commission 59 Town Hall Square, Falmouth, MA 02540 Telephone: 508-495-7440 Fax: 508.495.7443 email: [email protected] Certificate of Appropriateness & FOR OFFICE USE ONLY Administrative Review Application Application # ___________________ Received by Planning Department Application is hereby made for the issuance of a Certificate of Appropriateness on: under the provisions of Massachusetts General Law, Chapter 40C, as amended. Please check all the categories that apply: BUILDING CONSTRUCTION: __New __Addition __Renovation DEMOLITION/REMOVAL OF: __Building __Fence __Other:_____________________ TYPE OF BUILDING: __Residential __Commercial __Accessory/Other: ____________ EXTERIOR: __Roof __Siding __Windows __Doors __Other__________ OTHER STRUCTURES: __Fence __Wall __Flagpole __Lighting __Other_________ SIGN: __Please attach a completed “Town of Falmouth Sign Permit Application” PROPERTY ADDRESS:______________________________________________ MAP # __________________ PROPERTY OWNER’S NAME:________________________________________ PHONE __________________ OWNER’S SIGNATURE:______________________________________________ DATE ___________________ CONTRACTOR/AGENT:_____________________________________________ PHONE __________________ MAILING ADDRESS:_________________________________________________________________________ Please provide a brief description of the proposed work: Documents attached: Scaled drawings and photographs ___ addendum of existing conditions and ___ photographs proposed work must be provided. ___ -

Andrea I. Frank Christopher Silver Editors Beginnings, Global Movement and Future Prospects

The Urban Book Series Andrea I. Frank Christopher Silver Editors Urban Planning Education Beginnings, Global Movement and Future Prospects The Urban Book Series Aims and Scope The Urban Book Series is a resource for urban studies and geography research worldwide. It provides a unique and innovative resource for the latest developments in the field, nurturing a comprehensive and encompassing publication venue for urban studies, urban geography, planning and regional development. The series publishes peer-reviewed volumes related to urbanization, sustainabil- ity, urban environments, sustainable urbanism, governance, globalization, urban and sustainable development, spatial and area studies, urban management, urban infrastructure, urban dynamics, green cities and urban landscapes. It also invites research which documents urbanization processes and urban dynamics on a national, regional and local level, welcoming case studies, as well as comparative and applied research. The series will appeal to urbanists, geographers, planners, engineers, architects, policy makers, and to all of those interested in a wide-ranging overview of contemporary urban studies and innovations in the field. It accepts monographs, edited volumes and textbooks. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14773 Andrea I. Frank • Christopher Silver Editors Urban Planning Education Beginnings, Global Movement and Future Prospects 123 Editors Andrea I. Frank Christopher Silver School of Geography and Planning College of Design, Construction Cardiff University and Planning Cardiff University of Florida UK Gainesville, FL USA ISSN 2365-757X ISSN 2365-7588 (electronic) The Urban Book Series ISBN 978-3-319-55966-7 ISBN 978-3-319-55967-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-55967-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017937508 © Springer International Publishing AG 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

Mental Health Facilitiesin Massachusetts

THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE UNWANTED: CRISIS IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE COMMUNITY-SCALE INSTITUTION Case Study: Mental Health Facilities in Massachusetts by Christopher Pilkington B.A. Yale University 1977 Ed.M. Harvard University 197, SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1985 C Christopher Pilkington The author hereby grants M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author rVeZatment of Urban Studies and Planning May, 1985 Certified by Tunney F. Lee Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Acceped byPhillip L. Clay Head, Departmental Committee on Graduate Studies J s tt JUL 1 ? 1985 THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE UNWANTED. CRISIS IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE COMMUNITY- SCALE INSTITUTION CASE STUDY: MENTAL HEALTH FACILITIES IN MASSACHUSETTS c~M0 CHRIS PILKINGTON SPRING, 1985 ABSTRACT Thoughout history, social and economic forces combined to establish large, isolated public institutions as the traditional form of treatment for society's unwanted. Fueled by break- throughs in medicine and social services and a change in ideas about treatment, recent reformers have taken on the massive agenda of re-scaling the asylum and reintegrating its population within the community--an agenda which has only had mixed success. Among other obstacles, segmentation in the public budgeting and implementation process, and confusion as to the architectural goals of the new generation of institutional facilities needed to effect this change have reduced the capacity of reformers to overcome the still-strong forces to segregate, distance and warehouse the unwanted.