Dewart Transcript.Pdf (181.9Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank Press 1924–2020

perspectives KEN FULTON AND MARCIA MCNUTT Remembering Frank Press 1924–2020 Frank Press, portrait by Jon Friedman, 1995 rogress in the authoritative use of scientific evidence Press was born on December 4, 1924, and grew up in New to guide wise government policy is a story of people, York City, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants. He recalled ideas, and institutions. As an example, Frank Press being a poorly performing student in the public school Plaunched Issues in Science and Technology as a vehicle to system until sixth grade, when a pair of glasses allowed him provide a forum in which a community of experts could to read the blackboard. Early on, he developed an interest share their experiences, opinions, and proposals for in science from reading periodicals such as Popular Science advancing science in the public interest under the banner and Popular Mechanics, but it was a high school geology of a trusted, nonpartisan science policy institution. It is teacher who ignited his interest in the geosciences. While therefore most fitting that we highlight here Press’s many conducting an assigned magnetic survey of Van Cortland contributions to science policy through his ideas and the Park in the Bronx, he realized that with geophysics he could institutions he built. apply his aptitude for physics to explore the unknown. 20 ISSUES IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY perspectives Press completed a physics major at City College of New excitation of Earth’s free oscillations for the very first time, York in 1944 in just two and a half years, studying year- thus deriving new information about the structure of Earth’s round as was common during the war years. -

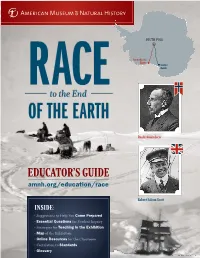

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

Dissertação O Processo Político Das Políticas Públicas Para As

O Processo Político de Construção das Políticas Públicas para as Alterações Climáticas José Carlos Martinho da Silva Dissertação de Mestrado em Sociologia - Políticas Públicas e NomeDesigualdades Completo do Sociais Autor Maio de 2019 Resumo As alterações climáticas de origem antropogénica constituem um problema ambiental sobre o qual se desenvolveram desde a década de 90 políticas públicas e tratados internacionais de grande relevância. O peso desta problemática nas agendas políticas e mediáticas tem sido crescente em diversas nações, inclusive em Portugal e na União Europeia (UE). Com efeito, a UE constitui-se hoje como um dos principais agentes mobilizados e mobilizadores de políticas sobre esta problemática, com políticas públicas robustas implementadas no contexto do protocolo de Quioto e de outras decisões tomadas na Convenção Quadro das Nações Unidas para as Alterações Climáticas. A ação internacional mais recente e ambiciosa promovida no âmbito da Convenção, ocorreu em 2015, o Acordo de Paris, mas foi recebida por uma renovada e estruturada oposição, nomeadamente a dos Estados Unidos da América (EUA), que com a sua saída do Acordo, despoletou desenvolvimentos imprevisíveis que representam atualmente um foco de preocupação e controvérsia, intensificando as interrogações face a um problema, que politicamente se veio a consolidar num desenho de políticas públicas com fortes implicações em diferentes áreas económicas, sociais e geopolíticas das diferentes nações e agrupamentos regionais representados na Convenção. Este trabalho procura abordar o problema político como um processo, e sobre este, desenvolver uma análise sociológica, tendo como enquadramento teórico a teoria de campo de Pierre Bourdieu. O foco deste trabalho foi o de compreender o início deste processo, eventualmente lançando as bases para um estudo posterior que alcance as suas diferentes fases, até ao momento presente. -

Presidential Files; Folder: 11/22/77; Container 52

11/22/77 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 11/22/77; Container 52 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf TIIE PRESIDENT'S SCHEDULE Tuesday - November 22,1977 8:15 Dr. Zbigniew Brz.ezinski The Oval Office . 8:45 .Hr . Frank Moore The Oval Office. 10:00 Medal of Science Awards. (Dr. Frank Press). ·Room 450, EOB. I \ 10:30 Mr. Jody Powell The Oval Office. 11:00 Presentation of Diplomatic Credentials. (Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski} - The Oval Office. 11:45 Vice President Walter F. Mondale, Admiral Stansfield Turner, and Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski. The Oval Office. 12:30 Lunch \..,-::_ th Hrs. Rosalynn Carter ·- The Ovctl Office. 2:00 Budget Review Meeting. (Mr. James Mcintyre). ( 2 hrs.) The Cabinet Room. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON \"~ Date: November 22, 1977 l\ vo\ \'~ MEMORANDUM t)lDifll FOR ACTION: '" FOR INFORMATION: Stu Eizenstat ~t""'"' Frank Moore (Les Francis)~ The Vice President Jack Watson Bob Lipshutz Jim Mcintyre FROM: Rick Hutcheson, Staff Secretary SUBJECT: Adams memo dated 11/22/77 re Response to the Boston Plan and Location of Rail Maintenance Facilit.y in the Northeast Corridor YOUR RESPONSE MUST BE DELIVERED TO THE STAFF SECRETARY BY: TIME: 11:00 AM DAY: Monday DATE: November 28, 1977 ACTION REQUESTED: _x_ Your comments Other: STAFF RESPONSE: __ I concur. __ No comment: Please note other comments below: PLEASE ATTACH THIS COPY TO MATERIAL SUBMITTED. If you have any questions or if you anticipate a delay in submitting the required material, please telephone the Staff Secretary immediately. -

Distribution of Marine Palynomorphs in Surface Sediments, Prydz Bay, Antarctica

DISTRIBUTION OF MARINE PALYNOMORPHS IN SURFACE SEDIMENTS, PRYDZ BAY, ANTARCTICA Claire Andrea Storkey A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Science in geology School of Earth Sciences Victoria University of Wellington April 2006 ABSTRACT Prydz Bay Antarctica is an embayment situated at the ocean-ward end of the Lambert Glacier/Amery Ice Shelf complex East Antarctica. This study aims to document the palynological assemblages of 58 surface sediment samples from Prydz Bay, and to compare these assemblages with ancient palynomorph assemblages recovered from strata sampled by drilling projects in and around the bay. Since the early Oligocene, terrestrial and marine sediments from the Lambert Graben and the inner shelf areas in Prydz Bay have been the target of significant glacial erosion. Repeated ice shelf advances towards the edge of the continental shelf redistributed these sediments, reworking them into the outer shelf and Prydz Channel Fan. These areas consist mostly of reworked sediments, and grain size analysis shows that finer sediments are found in the deeper parts of the inner shelf and the deepest areas on the Prydz Channel Fan. Circulation within Prydz Bay is dominated by a clockwise rotating gyre which, together with coastal currents and ice berg ploughing modifies the sediments of the bay, resulting in the winnowing out of the finer component of the sediment. Glacial erosion and reworking of sediments has created four differing environments (Prydz Channel Fan, North Shelf, Mid Shelf and Coastal areas) in Prydz Bay which is reflected in the palynomorph distribution. Assemblages consist of Holocene palynomorphs recovered mostly from the Mid Shelf and Coastal areas and reworked palynomorphs recovered mostly from the North Shelf and Prydz Channel Fan. -

Studies of Seismic Sources in Antarctica Using an Extensive Deployment of Broadband Seismographs Amanda Colleen Lough Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Summer 9-1-2014 Studies of Seismic Sources in Antarctica Using an Extensive Deployment of Broadband Seismographs Amanda Colleen Lough Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lough, Amanda Colleen, "Studies of Seismic Sources in Antarctica Using an Extensive Deployment of Broadband Seismographs" (2014). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1319. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1319 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences Dissertation Examination Committee: Douglas Wiens, Chair Jill Pasteris Philip Skemer Viatcheslav Solomatov Linda Warren Michael Wysession Studies of Seismic Sources in Antarctica Using an Extensive Deployment of Broadband Seismographs by Amanda Colleen Lough A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 St. Louis, Missouri © 2014, Amanda Colleen Lough Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. -

Page 1 0° 10° 10° 110° 110° 20° 20° 120° 120° 30° 30° 130° 130° 40

Bouvet I 50° 40° 30° 20° 10° 0° (Norway) 10° 20° 30° 40° 50° Marion I Prince Edward I e PRINCE EDWARD ISLANDS ea Ic (South Africa) t of S exten ) aximum 973-82 M rage 1 60° ar ave (10 ye SOUTH 60° SOUTH GEORGIA (UK) SANDWICH Crozet Is ISLANDS (France) (UK) R N 60° E H O T C U Antarctic Circle E H A A K O N A G V I O EO I S A N D T H E S O U T H E R N O C E A N R a Laurie I G ( t E V S T k A Powell I J . r u 70° ORCADAS (ARGENTINA) O E A S o b N A l L F lt d Stanley N B u a Coronation I R N r A N Rawson SIGNY (UK) E A I n Y ( U C A g g A G M R n K E E A E a i S S K R A T n V a Edition 6 SOUTH ORKNEY ST M Y I ) e E y FALKLAND ISLANDS (UK) R E S 70° N L R ø ISLANDS O A R E E A v M N N S Z a l Y I A k a IS ) L L i h EN BU VO ) v n ) IA id e A IM A O S e rs I L MAITRI N S r F L a a S QUARISEN E U B n J k L S F R i - e S ( r ) U (INDIA) v Kapp Norvegia P t e m s a N R U s i t ( u R i k A Puerto Deseado Selbukta a D e R u P A r V Y t R b A BORGMASSIVET s E A l N m (J A V FIMBULHEIME E l N y Comodoro Rivadavia u S N o r t IS A H o RIISER LARSENISEN u H t Clarence I J N K Z n E w W E o R Elephant I W E G E T IN o O D m d N E S T SØR-RONDANE z n R I V nH t Y O ro a y 70° t S E R E e O u S L P sl a P N A R e RS L I B y A r H O e e G See Inset d VESTFJELLA LL C G b AV g it en o E H n NH M n s o J N e n EIA a h d E C s e NE T W E M F S e S n I R n r u T h King George I t a b i N m N O d i E H r r N a Joinville I A O B . -

No Turning Back • Rothera Fire • Kayaking the Antarctic • Summer Tours • 2003 Solar Eclipse • Tangan Expedition!

The Journal of the New Zealand Antarctic Society Vol 19, No. 2, 2001 No Turning Back • Rothera Fire • Kayaking the Antarctic • Summer Tours • 2003 Solar Eclipse • Tangan Expedition! Antarctic COVER PICTURE CONTENTS Kayaking in Antarctica SCAR Symposium Rothera Fire Plans to Locate Endurance Solar Eclipse in 2003 Cover photograph: New Zealand kayakers in the Letter to the Editor Antarctic Peninsula north of Enterprise Island. Photo: Graham Charles. The story of last season's Terrorist Attacks Affect Antarctic Planning epic trip is summarised in Antarctic, Vol. 18, no. 3 & 4, p. 58. More photographs opposite. Adventure Tourism Volume 19, No. 2, 2001 No Turning Back - Colin Monteath Issue No. 177 ANTARCTIC is published quarterly by the Over My Shoulder - Dogs on Ice New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc., ISSN 0003-5327. Please address all editorial enquiries to The Editor, NZ Antarctic Society, PO Box 404, Christchurch, or Review - A First Rate Tragedy email: [email protected]. Printed by Herald Communications, 52 Bank Street, Timaru, New Zealand. Review - Antarctica Unveiled Tribute - W. Frank Ponder Science - Tangaroa Explores Ross Sea Science - First Foucault Pendulum at Pole Antarctic Rubbish Volome 19, No. 2,2001 Antarctic NEWS Seals, Subglacial Lakes and Ultra-violet Radiation Highlights of the eighth SCAR Biology Symposium By Dr Clive Howard-Williams here were APIS, Subglacial lakes and The symposium also hosted a UV Radiation. workshop and several lectures on the The eighth SCAR international Bi The results of the Antarctic Pack Ice status of the Earth's latest unexplored ology Symposium was held in Am Seals (APIS) programme are appear large ecosystem: the sub-glacial lakes sterdam between 27 August and 5 ing in the literature, following the beneath the 3.5 km thick Antarctic ice September 2001. -

(2014). Dynamic Response of Antarctic Ice Shelves to Bedrock Uncertainty. Cryosphere, 8(4), 1561-1576

Sun, S., Cornford, S. L., Liu, Y., & Moore, J. C. (2014). Dynamic response of Antarctic ice shelves to bedrock uncertainty. Cryosphere, 8(4), 1561-1576. https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-8-1561-2014 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.5194/tc-8-1561-2014 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via EGU at http://www.the-cryosphere.net/8/1561/2014/. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ The Cryosphere, 8, 1561–1576, 2014 www.the-cryosphere.net/8/1561/2014/ doi:10.5194/tc-8-1561-2014 © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Dynamic response of Antarctic ice shelves to bedrock uncertainty S. Sun1, S. L. Cornford2, Y. Liu1, and J. C. Moore1,3,4 1College of Global Change and Earth System Science, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China 2School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1SS, UK 3Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, PL122, 96100 Rovaniemi, Finland 4Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Villavägen 16, Uppsala, 75236, Sweden Correspondence to: J. C. Moore ([email protected]) Received: 2 January 2014 – Published in The Cryosphere Discuss.: 21 January 2014 Revised: 27 June 2014 – Accepted: 1 July 2014 – Published: 21 August 2014 Abstract. -

An "Exceedingly Delicate Undertaking": Sino-American

An "exceedingly delicate undertaking": Sino-American science diplomacy, 1966–78 LSE Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/102296/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Millwood, Peter (2019) An "exceedingly delicate undertaking": Sino-American science diplomacy, 1966–78. Journal of Contemporary History. ISSN 0022-0094 (In Press) Reuse Items deposited in LSE Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the LSE Research Online record for the item. [email protected] https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/ An “Exceedingly Delicate Undertaking”: Sino-American Science Diplomacy, 1966–78 Pete Millwood International History Department, London School of Economics In the first half of the twentieth century, China sought to modernize through opening to the world. Decades of what would become a century of humiliation had disabused the country of its previous self-perceived technological superiority, as famously expressed by Emperor Qianlong to the British envoy George Macartney in 1793. The Chinese had instead become convinced that they needed knowledge from outside to become strong enough to resist imperial aggression. No country encouraged this opening more than the United States. Americans threw money and expertise at the training of Chinese students and intellectuals. The Rockefeller Foundation’s first major overseas project was the creation of China’s finest medical college and other US institutions followed Rockefeller’s lead by establishing dozens of Chinese universities and technical schools to train a new generation of Chinese scientists. -

ALBERT PADDOCK CRARY 1911-1987 Noted Exploration Geophysicist Albertp

OBITUARY / 89 ALBERT PADDOCK CRARY 1911-1987 Noted exploration geophysicist AlbertP. Crary diedin Wash- exceptional man becauseof his abilityto combine his genius as a ington, D.C., Thursday afternoon, October 29, 1987, of com- scientific explorer with his qualities as a human being. For this plications following spinal tumor surgery.Known as the “father” he will be remembered by those of us who werehis compatriots of theAmerican Antarctic science program and, earlier, a in science and friends inlife. ” leading researcher inthe Arctic, Crary conducted a broad range “Bert Crary, perhaps more than any other person, brought of scientific observationsin Polar regions, incidentally becom- modem geophysics to the study of ice and the landin the polar ing the first person to have set foot on both North and South regions,” said Dr. Mark F. Meier, director of the Institute of Poles. Arctic and AlpineResearch, University of Colorado. Science editor of The New York Times, Walter S. Sullivan, Jr., said, “To me, Bert Crary represented the finest in polar explorers and scientists. In contrast to so many, he was not driven by vanityor ego but by the advancementof knowledge. And he was a wonderful humanbeing.” Other colleagues reacted similarlyto news of his death. Dr. William O. Field, Jr., former head of theDepartment of Exploration and Field Researchof the American Geographical Society, found him “a great scientist, a great companion, and a great friend. I’m proud to have been associated withhim.” Dr. Richard P. Goldthwait, founder and first director of the Institute of Polar Studies, The Ohio State University, said, “He was a great man at the endof an era of getting into the Antarctic and learning aboutit.