The Mistake of 1937: a General Equilibrium Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

• 1937 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE Lt

• 1937 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE Lt. Comdr. Joseph Greenspun to be commander with Victor H. Krulak Robert E~ Hammel rank from May 1, 1937; and George C. Ruffin, Jr. Frank C. Tharin District Commander William M. Wolff to be district com Harold 0. Deakin Henry W. G. Vadnais mander with the rank of lieutenant commander from Janu Maurice T. Ireland John W~Sapp, Jr. ary 31, 193'7. Samuel R. Shaw Samuel F. Zeiler The PRESIDING OFFICER. '!he reports will be placed Robert S. Fairweather Lawrence B. Clark on the Executive Calendar. , Joseph P, Fuchs Lehman H. Kleppinger If there be no further reports of committees, the clerk Henry W. Buse, Jr. Floyd B. Parks will state the nomination on the Executive Calendar. Bennet G. Powers John E. Weber POSTMASTER CONFIRMATION The legislative clerk read the nomination of L. Elizabeth Executive nomination confirmed by the Senate June 8 Dunn to be postmaster at Conchas Dam, N.Mex. (legislative day of June 1>. 1937 The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without objection, the nomination is confirmed. POSTMASTER That concludes the Executive Calendar. NEW MEXICO ADJOURNMENT TO MONDAY L. Elizabeth Dunn, Conchas Dam. The Senate resumed legislative session. Mr. BARKLEY. I move that the Senate adjourn until WITHDRAWAL 12 o'clock noon on Monday next. Executive nomination withdrawn from the Senate June 3 The motion was agreed to; and (at 2 o'clock and 45 min (legislative day of June 1), 1937 utes p. m.) the Senate adjourned until Monday, June '1, 1937. WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION at 12 o'clock meridian. Ron Stevens to be State administrator in the Works Prog ress Administration for Oklahoma. -

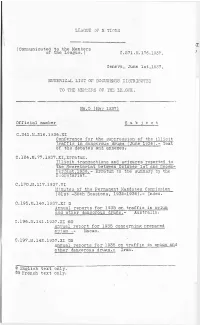

C.271.M.176.1937 Geneva, June 1St,1937, NUMERICAL LIST OF

LEAGUE OF N.-..TIONS Œ (Communicated to the Members of the League.) C .271.M.176.1937 7 Geneva, June 1st,1937, NUMERICAL LIST OF DOCUMENTS DISTRIBUTED TO THE MEMBERS OF THE LEAGUE. No.5 (May 1957) Official number S u b j e c t C.341,M,216.1936.XI Conference for the suppression of the illicit traffic in dangerous drugs (June 1956).-~Text of the debates and annexes. C. 124.M.77.1957,XI,Erratum. Illicit transactions and seizures reported to the Secretariat between October 1st and Decem- berSlst,1936.- Erratum to the summary by the Secretariat. C.170.M.117.1937,VI Minutes of the Permanent Mandates Commission (21st -30th Sessions, 1932-1936).- Index. C.195.M.140.1937.XI @ Annual reports for 1935 or. traffic in opium and other dangerous drugs.- Australia. C.196.M.141.1937.XI Annual report for 1955 concerning prepared opium .- Macao. C.197.M.142.1957.XI @@ Annual reports for 1955 on traffic in opium and other dangerous drugs.- Iran. ® English text only. French text only. - 2 C.198.M.143.1937.XI @ Annual reports for 1935 on traffic in opium and other dangerous drugs.- Portugal and neighbouring Islands. C.201.M.145.1937.XI © Annual reports for 1935 on traffic in opium and other dangerous drugs.- Portuguese Colonies of Angola , Cape Verde, Guinea, Portuguese India, Mozambique, San Thome and Principe and Timor. C.204.M.147.1957.XI @ Annual reports for 1935 concerning prepared opium . - Indo-China. C .206.M.149,1957„XI and Annex. Laws and regulations concerning narcotics_in United States of America,- Note by the Secre tary General,and Treasury Decisions Nos. -

Soviet Intervention in the Spanish Civil War: Review Article

Ronald Radosh Sevostianov, Mary R. Habeck, eds. Grigory. Spain Betrayed: The Soviet Union in the Spanish Civil War. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001. xxx + 537 pp. $35.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-300-08981-3. Reviewed by Robert Whealey Published on H-Diplo (March, 2002) Soviet Intervention in the Spanish Civil War: the eighty-one published documents were ad‐ Review Article dressed to him. Stalin was sent at least ten. Stalin, [The Spanish language uses diacritical marks. the real head of the Soviet Union, made one direct US-ASCII will not display them. Some words, order to the Spanish government, on the conser‐ therefore, are written incompletely in this re‐ vative side. After the bombing of the pocket bat‐ view] tleship Deutschland on 29 May 1937 (which en‐ raged Hitler), Stalin said that the Spanish Republi‐ This collection is actually two books wrapped can air force should not bomb German or Italian in a single cover: a book of Soviet documents pre‐ vessels. (Doc 55.) sumably chosen in Moscow by Grigory Sevos‐ tianov and mostly translated by Mary Habeck. From reading Radosh's inadequate table of Then the Soviet intervention in Spain is narrated contents, it is not easy to discover casually a co‐ and interpreted by the well-known American his‐ herent picture of what the Soviets knew and were torian Ronald Radosh. Spain Betrayed is a recent saying during the civil war. Archival information addition to the continuing Yale series, "Annals of tends to get buried in the footnotes and essays Communism," edited with the cooperation of Rus‐ scattered throughout the book, and there is no sian scholars in Moscow. -

Inventory Dep.288 BBC Scottish

Inventory Dep.288 BBC Scottish National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Typescript records of programmes, 1935-54, broadcast by the BBC Scottish Region (later Scottish Home Service). 1. February-March, 1935. 2. May-August, 1935. 3. September-December, 1935. 4. January-April, 1936. 5. May-August, 1936. 6. September-December, 1936. 7. January-February, 1937. 8. March-April, 1937. 9. May-June, 1937. 10. July-August, 1937. 11. September-October, 1937. 12. November-December, 1937. 13. January-February, 1938. 14. March-April, 1938. 15. May-June, 1938. 16. July-August, 1938. 17. September-October, 1938. 18. November-December, 1938. 19. January, 1939. 20. February, 1939. 21. March, 1939. 22. April, 1939. 23. May, 1939. 24. June, 1939. 25. July, 1939. 26. August, 1939. 27. January, 1940. 28. February, 1940. 29. March, 1940. 30. April, 1940. 31. May, 1940. 32. June, 1940. 33. July, 1940. 34. August, 1940. 35. September, 1940. 36. October, 1940. 37. November, 1940. 38. December, 1940. 39. January, 1941. 40. February, 1941. 41. March, 1941. 42. April, 1941. 43. May, 1941. 44. June, 1941. 45. July, 1941. 46. August, 1941. 47. September, 1941. 48. October, 1941. 49. November, 1941. 50. December, 1941. 51. January, 1942. 52. February, 1942. 53. March, 1942. 54. April, 1942. 55. May, 1942. 56. June, 1942. 57. July, 1942. 58. August, 1942. 59. September, 1942. 60. October, 1942. 61. November, 1942. 62. December, 1942. 63. January, 1943. -

THE No. 2 July, 1937

THE RHEOLOGY LEAFLET navza §EL Publication of the SOCIETY OF RHEOLOGY No. 2 July, 1937 NoTH. 2 E KHEOLOG7rdvra getY LEAFLEJuly, 193T7 This is the second issue of the Rheology Leaflet. The Editor would be glad of suggestions for future numbers. He would apprec- iate, too, news items telling of temporary or permanent changes of . address, new publications, new discoveries, etc. Address: Wheeler P. Davey, Editor Society of Rheology School of Chemistry and Physics The Pennsylvania State College State College, Pennsylvania OUR NEXT MEETING The annual meeting of the Society of Rheology will be held in Akron, Ohio, October 22 and 23, 1937. The Hotel Mayflower will be the headquarters for this meeting. The technical sessions of the Society will probably be held in the Hotel. Tentative arrangements now include trips through the Tire Div- ision of the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, the Mechanical Goods Division of the B. F. Goodrich Company, and the Laboratories of the Guggenheim Airship Institute. The personnel of the local committee will be: W. F. Busse, B. F. Goodrich Company A. M. Keuthe, Guggenheim Airship Institute J. W. Liska, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company J. H. Dillon, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company With this committee we are assured of the best accommodations as well as all we could desire in the way of entertainment. In addition, since Akron is the capital of the rubber industry, the multitude of direct and indirect applications of Rheology employed there will prove of interest to our membership. Akron is close to the ideal loca- tion for a meeting of our Society, as a recent analysis of the geograph- ical distribution of our membership has shown that our "center of gravity" lies somewhere in Ohio. -

Leon Trotsky and the Barcelona "May Days" of 1937

Received: 20 May 2019 Revised: 2 July 2019 Accepted: 19 August 2019 DOI: 10.1111/lands.12448 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Leon Trotsky and the Barcelona "May Days" of 1937 Grover C. Furr Department of English, Montclair State University, Montclair, New Jersey Abstract During the past several decades, evidence has come to Correspondence light which proves that Leon Trotsky lied a great deal to Grover C. Furr, Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ 07043. cover up his conspiracies against the Stalin regime in the E-mail: [email protected] USSR. References to the studies that reveal Trotsky's falsehoods and conspiracies are included in the article. The present article demonstrates how this evidence changes the conventional understanding of the assassina- tions of some Trotskyists at the hands of the Soviet NKVD and Spanish communists, during the Spanish Civil War. A brief chronology of the Barcelona May Days revolt of 1937 is appended. During the past several decades evidence has come to light which proves that Leon Trotsky lied a great deal in order to cover up his conspiracies against the Stalin regime in the USSR. In 1980 and subsequent years Pierre Broué, the foremost Trotskyist historian in the world at the time, discovered that Trotsky approved the “bloc of Rights and Trotskyites,” whose existence was the most important charge in the Moscow Trials, and had maintained contact with clandestine supporters with whom he publicly claimed to have broken ties. Arch Getty discovered that Trotsky had specifically contacted, among others, Karl Radek, while he and Radek continued to attack each other in public. -

Floods of December 1937 in Northern California by H

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Water- Supply Paper 843 FLOODS OF DECEMBER 1937 IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA BY H. D. McGLASHAN AND R. C. BRIgGS Prepared in cooperation with the I*? ;* FEDERAL EMERGENCY ADMINISTRATION OF PUBLIC WORKS, BUREAU OF RECI&MATjON AND STATE OF CALIFORNIA ~- tc ; LtJ -r Q-. O 7 D- c- c fiD : UNITED STATES l*< '.^ 0 r GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE « EJ WASHINGTON : 19.39 J* *£. ? fJ? For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. - - - Price 60 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract .................................... 1 Introduction .................................. 2 Administration and personnel .......................... 4 Acknowledgments. ................................ 5 General features of the floods ......................... 6 ICeteorologic and hydrologic conditions ..................... 22 Antecedent conditions ........................... 23 Precipitation ............................... 24 General features ............................ 25 Distribution .............................. 44 Temperature ................................ 56 Snow .................................... 65 Sierra Nevada slopes tributary to south half of Central Valley ..... 68 Sierra Nevada slopes tributary to north half of Central Valley ..... 70 Sierra Nevada slopes tributary to the Great Basin ........... 71 Determination of flood discharges ....................... 71 General discussion ............................. 71 Extension of rating -

'Against the State': a Genealogy of the Barcelona May Days (1937)

Articles 29/4 2/9/99 10:15 am Page 485 Helen Graham ‘Against the State’: A Genealogy of the Barcelona May Days (1937) The state is not something which can be destroyed by a revolution, but is a condition, a certain relationship between human beings, a mode of human behaviour; we destroy it by contracting other relationships, by behaving differently.1 For a European audience, one of the most famous images fixing the memory of the Spanish Civil War is of the street fighting- across-the-barricades which occurred in Barcelona between 3 and 7 May 1937. Those days of social protest and rebellion have been represented in many accounts, of which the single best known is still George Orwell’s contemporary diary account, Homage to Catalonia, recently given cinematic form in Ken Loach’s Land and Freedom. It is paradoxical, then, that the May events remain among the least understood in the history of the civil war. The analysis which follows is an attempt to unravel their complexity. On the afternoon of Monday 3 May 1937 a detachment of police attempted to seize control of Barcelona’s central telephone exchange (Telefónica) in order to remove the anarchist militia forces present therein. News of the attempted seizure spread rapidly through the popular neighbourhoods of the old town centre and port. By evening the city was on a war footing, although no organization — inside or outside government — had issued any such command. The next day barricades went up in central Barcelona; there was a generalized work stoppage and armed resistance to the Catalan government’s attempt to occupy the telephone exchange. -

Until2 February 1938 When He Was Appointed President of Thev Geheime Kabinettsrat (Secret Cabinet Council), a Newly Create

(Neumann rough dr'a,ft, unedited) Von Neurath joined the cabinet of the defendant von after a long diplomatic career and, on 2 June 1932/ was ma d< Foreign Minister at the ap;e of 59« Re retained this pbsitib * . until2 February 1938 when he was appointed President of thev Geheime Kabinettsrat (Secret Cabinet Council), a newly create . institution, which he headed until the downfall of Nazism» \ As a member of the von Pap en cabinet and later under the. Hitler regime, the defendant was -one of the foremost protagonil of Germany's aggressive foreign policy the main points of whic were : 1) The abrogation of the Treaty of Versailles y, 2) ' The incorporation of all "racial" Germans living outs: German sovereignty into the German Reich, specifically the' incorporation of Austria» The defendant's greatest contribution to" the victory of Nazism and the preparation for aggressive war was the'large pa# he played, as one of Germany's most outstanding representative of the aristocracy and of the high civil service, in bringing:'. about the alliance between the new ruling groups represented the Nazi Party and the old reactionary ruling groups composed I of Junkers, aristocrats, generalsand industrialists and high Noivll servants. He sealed this union by accepting on Hitler^sjj reqaest the position of a Re ichsprotektor of Czechoslovakia after the conquest of that country (18 March 1939). On 22 September 1940, Hitler awarded him the War Merit Cross Is t Claä • BPSWRF^: )gnitu' t'aichprbtektor. Ho received the . Party's Golden Honor Badgey Hitler personnally made him y ?norary SS Gruppenfuehrer on September 1937, and SS ' iqr gruppenfuehrer on 21 June 1943. -

Spanish Civil War 1936–9

CHAPTER 2 Spanish Civil War 1936–9 The Spanish Civil War 1936–9 was a struggle between the forces of the political left and the political right in Spain. The forces of the left were a disparate group led by the socialist Republican government against whom a group of right-wing military rebels and their supporters launched a military uprising in July 1936. This developed into civil war which, like many civil conflicts, quickly acquired an international dimension that was to play a decisive role in the ultimate victory of the right. The victory of the right-wing forces led to the establishment of a military dictatorship in Spain under the leadership of General Franco, which would last until his death in 1975. The following key questions will be addressed in this chapter: + To what extent was the Spanish Civil War caused by long-term social divisions within Spanish society? + To what extent should the Republican governments between 1931 and 1936 be blamed for the failure to prevent civil war? + Why did civil war break out? + Why did the Republican government lose the Spanish Civil War? + To what extent was Spain fundamentally changed by the civil war? 1 The long-term causes of the Spanish Civil War Key question: To what extent was the Spanish Civil War caused by long-term social divisions within Spanish society? KEY TERM The Spanish Civil War began on 17 July 1936 when significant numbers of Spanish Morocco Refers military garrisons throughout Spain and Spanish Morocco, led by senior to the significant proportion of Morocco that was army officers, revolted against the left-wing Republican government. -

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS September 1937

SEPTEMBER 1937 SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE WASHINGTON VOLUME 17 NUMBER 9 A Review of Economic Changes during the elapsed period of 1937 is presented in the article on page 12. The improvement this year has been substantial, but the rate of increase has tended to slacken in recent months. NATIONAL INCOME has been much larger than in 1936 and this further gain in the dollar figures has meant an increase in ''rear' income. This expansion has reflected the sharp rise in labor income, the gain in income from agriculture and other business enterprises, and the rapid rise in dividend payments. CASH FARM INCOME from marketings and Government payments for the full year 1937 is estimated by the Department of Agriculture at $9,000,000,000, an increase of 14 percent over the total for 1936, and the largest income since 1929. Industrial output for the first 8 months was about 15 percent larger than in the corresponding period of 1936. The increase in freight-car loadings was almost as large, while that for retail trade was somewhat less. OTHER FEATURES of the general business situation are sum- marized, and a table provides data on the extent of the gains over 1932 and 1936. A special chart on page 4 affords a quick comparison of six principal economic series for the 1929-37 period. UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DANIEL C. ROPER, Secretary BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE ALEXANDER V. DYE, Director SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS Prepared in the DIVISION OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH ROY G.