Scientia Magna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Clasification of Known Root Prime-Generating

Special properties of the first absolute Fermat pseudoprime, the number 561 Marius Coman Bucuresti, Romania email: [email protected] Abstract. Though is the first Carmichael number, the number 561 doesn’t have the same fame as the third absolute Fermat pseudoprime, the Hardy-Ramanujan number, 1729. I try here to repair this injustice showing few special properties of the number 561. I will just list (not in the order that I value them, because there is not such an order, I value them all equally as a result of my more or less inspired work, though they may or not “open a path”) the interesting properties that I found regarding the number 561, in relation with other Carmichael numbers, other Fermat pseudoprimes to base 2, with primes or other integers. 1. The number 2*(3 + 1)*(11 + 1)*(17 + 1) + 1, where 3, 11 and 17 are the prime factors of the number 561, is equal to 1729. On the other side, the number 2*lcm((7 + 1),(13 + 1),(19 + 1)) + 1, where 7, 13 and 19 are the prime factors of the number 1729, is equal to 561. We have so a function on the prime factors of 561 from which we obtain 1729 and a function on the prime factors of 1729 from which we obtain 561. Note: The formula N = 2*(d1 + 1)*...*(dn + 1) + 1, where d1, d2, ...,dn are the prime divisors of a Carmichael number, leads to interesting results (see the sequence A216646 in OEIS); the formula M = 2*lcm((d1 + 1),...,(dn + 1)) + 1 also leads to interesting results (see the sequence A216404 in OEIS). -

Sequences of Primes Obtained by the Method of Concatenation

SEQUENCES OF PRIMES OBTAINED BY THE METHOD OF CONCATENATION (COLLECTED PAPERS) Copyright 2016 by Marius Coman Education Publishing 1313 Chesapeake Avenue Columbus, Ohio 43212 USA Tel. (614) 485-0721 Peer-Reviewers: Dr. A. A. Salama, Faculty of Science, Port Said University, Egypt. Said Broumi, Univ. of Hassan II Mohammedia, Casablanca, Morocco. Pabitra Kumar Maji, Math Department, K. N. University, WB, India. S. A. Albolwi, King Abdulaziz Univ., Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Mohamed Eisa, Dept. of Computer Science, Port Said Univ., Egypt. EAN: 9781599734668 ISBN: 978-1-59973-466-8 1 INTRODUCTION The definition of “concatenation” in mathematics is, according to Wikipedia, “the joining of two numbers by their numerals. That is, the concatenation of 69 and 420 is 69420”. Though the method of concatenation is widely considered as a part of so called “recreational mathematics”, in fact this method can often lead to very “serious” results, and even more than that, to really amazing results. This is the purpose of this book: to show that this method, unfairly neglected, can be a powerful tool in number theory. In particular, as revealed by the title, I used the method of concatenation in this book to obtain possible infinite sequences of primes. Part One of this book, “Primes in Smarandache concatenated sequences and Smarandache-Coman sequences”, contains 12 papers on various sequences of primes that are distinguished among the terms of the well known Smarandache concatenated sequences (as, for instance, the prime terms in Smarandache concatenated odd -

Conjecture of Twin Primes (Still Unsolved Problem in Number Theory) an Expository Essay

Surveys in Mathematics and its Applications ISSN 1842-6298 (electronic), 1843-7265 (print) Volume 12 (2017), 229 { 252 CONJECTURE OF TWIN PRIMES (STILL UNSOLVED PROBLEM IN NUMBER THEORY) AN EXPOSITORY ESSAY Hayat Rezgui Abstract. The purpose of this paper is to gather as much results of advances, recent and previous works as possible concerning the oldest outstanding still unsolved problem in Number Theory (and the most elusive open problem in prime numbers) called "Twin primes conjecture" (8th problem of David Hilbert, stated in 1900) which has eluded many gifted mathematicians. This conjecture has been circulating for decades, even with the progress of contemporary technology that puts the whole world within our reach. So, simple to state, yet so hard to prove. Basic Concepts, many and varied topics regarding the Twin prime conjecture will be cover. Petronas towers (Twin towers) Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification: 11A41; 97Fxx; 11Yxx. Keywords: Twin primes; Brun's constant; Zhang's discovery; Polymath project. ****************************************************************************** http://www.utgjiu.ro/math/sma 230 H. Rezgui Contents 1 Introduction 230 2 History and some interesting deep results 231 2.1 Yitang Zhang's discovery (April 17, 2013)............... 236 2.2 "Polymath project"........................... 236 2.2.1 Computational successes (June 4, July 27, 2013)....... 237 2.2.2 Spectacular progress (November 19, 2013)........... 237 3 Some of largest (titanic & gigantic) known twin primes 238 4 Properties 240 5 First twin primes less than 3002 241 6 Rarefaction of twin prime numbers 244 7 Conclusion 246 1 Introduction The prime numbers's study is the foundation and basic part of the oldest branches of mathematics so called "Arithmetic" which supposes the establishment of theorems. -

Number Theory Boring? Nein!

Running head: PATTERNS IN NINE 1 Number Theory Boring? Nein! Discerning Patterns in Multiples of Nine Gina Higgins Mathematical Evolutions Jenny McCarthy, Jonathan Phillips Summer Ventures in Science and Mathematics The University of North Carolina at Charlotte PATTERNS IN NINE 2 Abstract This is the process Gina Higgins went through in order to prove that the digital sum of a whole, natural number multiplied by nine would always equal nine. This paper gives a brief history on the number nine and gives a color coded, three-hundred row chart of multiplies of nine as an example and reference. Basic number theory principles were applied with Mathematical Implementation to successfully create a method that confirmed the hypothesis that the digital root of every product of nine equals nine. From this method could evolve into possible future attempts to prove why the digital root anomaly occurred. PATTERNS IN NINE 3 The number nine is the largest digit in a based ten number (decimal) system. In many ancient cultures such as China, India and Egypt, the number nine was a symbol of strength representing royalty, religion or powerful enemies (Mackenzie, 2005). The symbol for the number nine used most commonly today developed from the Hindu-Arabic System written in the third century. Those symbols developed from the Brahmi numerals found as far back as 300 BC. (Ifrah, 1981) Figure 1 Number theory is a branch of mathematics dealing specifically with patterns and sequences found in whole numbers. It was long considered the purest form of mathematics because there was not a practical application until the 20th century when the computer was invented. -

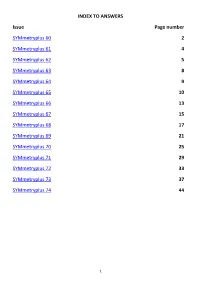

INDEX to ANSWERS Issue Page Number Symmetryplus 60 2

INDEX TO ANSWERS Issue Page number SYMmetryplus 60 2 SYMmetryplus 61 4 SYMmetryplus 62 5 SYMmetryplus 63 8 SYMmetryplus 64 9 SYMmetryplus 65 10 SYMmetryplus 66 13 SYMmetryplus 67 15 SYMmetryplus 68 17 SYMmetryplus 69 21 SYMmetryplus 70 25 SYMmetryplus 71 29 SYMmetryplus 72 33 SYMmetryplus 73 37 SYMmetryplus 74 44 1 ANSWERS FROM ISSUE 60 SOME TRIANGLE NUMBERS – 2 Many thanks to Andrew Palfreyman who found five, not four solutions! 7 7 7 7 7 1 0 5 3 0 0 4 0 6 9 0 3 9 4 6 3 3 3 3 1 Grid A 6 6 1 3 2 6 2 0 1 6 0 0 Grid B CROSSNUMBER Many thanks again to Andrew Palfreyman who pointed out that 1 Down and 8 Across do not give unique answers so there are four possible solutions. 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 4 4 8 1 4 4 8 1 4 4 8 1 4 4 8 3 3 3 3 3 9 1 9 8 9 1 9 3 9 1 9 8 9 1 9 4 5 4 5 4 5 4 5 2 3 1 0 2 3 1 0 2 3 1 0 2 3 1 0 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 1 0 9 8 1 0 9 8 1 0 9 8 1 0 9 8 8 9 8 9 8 9 8 9 3 6 1 0 3 6 1 0 9 6 1 0 9 6 1 0 10 10 10 10 5 3 4 3 5 3 4 3 5 3 4 3 5 3 4 3 TREASURE HUNTS 12, 13 12 This is a rostral column in St Petersburg, Russia. -

From Vortex Mathematics to Smith Numbers: Demystifying Number Structures and Establishing Sieves Using Digital Root

SCITECH Volume 15, Issue 3 RESEARCH ORGANISATION Published online: November 21, 2019| Journal of Progressive Research in Mathematics www.scitecresearch.com/journals From Vortex Mathematics to Smith Numbers: Demystifying Number Structures and Establishing Sieves Using Digital Root Iman C Chahine1 and Ahmad Morowah2 1College of Education, University of Massachusetts Lowell, MA 01854, USA 2Retired Mathematics Teacher, Beirut, Lebanon Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract: Proficiency in number structures depends on a continuous development and blending of intricate combinations of different types of numbers and its related characteristics. The purpose of this paper is to unpack the mechanisms and underlying notions that elucidate the potential process of number construction and its inherent structures. By employing the concept of digital root, we show how juxtaposed assumptions can play in delineating generalized models of number structures bridging the abstract, the numerical, and the physical worlds. While there are numerous proposed ways of constructing Smith numbers, developing a generalized algorithm could help provide a unified approach to generating number structures with inherent commonalities. In this paper, we devise a sieve for all Smith numbers as well as other related numbers. The sieve works on the principle of digital roots of both Sd(N), the sum of the digits of a number N and that of Sp(N), the sum of the digits of the extended prime divisors of N. Starting with Sp(N) = Sp(p.q.r…), where p,q,r,…, are the prime divisors whose product yields N and whose digital root (n) equals to that of Sd(N) thus Sd(N) = n + 9x; x є N. -

Fermat Pseudoprimes

1 TWO HUNDRED CONJECTURES AND ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY OPEN PROBLEMS ON FERMAT PSEUDOPRIMES (COLLECTED PAPERS) Education Publishing 2013 Copyright 2013 by Marius Coman Education Publishing 1313 Chesapeake Avenue Columbus, Ohio 43212 USA Tel. (614) 485-0721 Peer-Reviewers: Dr. A. A. Salama, Faculty of Science, Port Said University, Egypt. Said Broumi, Univ. of Hassan II Mohammedia, Casablanca, Morocco. Pabitra Kumar Maji, Math Department, K. N. University, WB, India. S. A. Albolwi, King Abdulaziz Univ., Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Mohamed Eisa, Dept. of Computer Science, Port Said Univ., Egypt. EAN: 9781599732572 ISBN: 978-1-59973-257-2 1 INTRODUCTION Prime numbers have always fascinated mankind. For mathematicians, they are a kind of “black sheep” of the family of integers by their constant refusal to let themselves to be disciplined, ordered and understood. However, we have at hand a powerful tool, insufficiently investigated yet, which can help us in understanding them: Fermat pseudoprimes. It was a night of Easter, many years ago, when I rediscovered Fermat’s "little" theorem. Excited, I found the first few Fermat absolute pseudoprimes (561, 1105, 1729, 2465, 2821, 6601, 8911…) before I found out that these numbers are already known. Since then, the passion for study these numbers constantly accompanied me. Exceptions to the above mentioned theorem, Fermat pseudoprimes seem to be more malleable than prime numbers, more willing to let themselves to be ordered than them, and their depth study will shed light on many properties of the primes, because it seems natural to look for the rule studying it’s exceptions, as a virologist search for a cure for a virus studying the organisms that have immunity to the virus. -

Digital Roots and Their Properties

IOSR Journal of Mathematics (IOSR-JM) e-ISSN: 2278-5728, p-ISSN: 2319-765X. Volume 11, Issue 1 Ver. III (Jan - Feb. 2015), PP 19-24 www.iosrjournals.org Digital Roots and Their Properties Aprajita1, Amar Kumar2 1(Department of Mathematics, J R S College, Jamalpur T M Bhagalpur University Bhagalpur, INDIA) 2(Department of Mathematics, J R S College, Jamalpur T M Bhagalpur University Bhagalpur, INDIA) Abstract: In this paper we want to highlight the properties of digital root and some result based on digital root. There are many interesting properties of digital root. We can also study nature of factors of a given number based on Vedic square and then we can implement this concept for an algorithm to find out a number is prime or not. Keywords: Digital Roots, factors, Integral roots, partition, Vedic square, Primality test. I. Introduction In recreational number theory (A. Gray [1]]) was the first to apply “digital root” but their application had not been previously recognized as relevant. Many other authors have also discussed on the same topics on different way but here we try to discuss the same in a manner which is different from all. Generally, digital root of any natural number is the digit obtained by adding the digits of the number till a single digit is obtained (see [2]) . We can define digital root of a number as: dr: N D where N is the set of natural numbers and D 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 and dr() a sum of digits of the number „a‟ till single digit is obtained. -

A Clasification of Known Root Prime-Generating

Another infinite sequence based on mar function that abounds in primes and semiprimes Marius Coman email: [email protected] Abstract. In one of my previous paper, namely “The mar reduced form of a natural number”, I introduced the notion of mar function, which is, essentially, nothing else than the digital root of a number, and I also presented, in another paper, a sequence based on mar function that abounds in primes. In this paper I present another sequence, based on a relation between a number and the value of its mar reduced form (of course not the intrisic one), sequence that seem also to abound in primes and semiprimes. Let’s consider the sequence of numbers m(n), where n is odd and m is equal to x*y + n, where x = 2*mar n + 2 and y = 2*mar n – 2, if y ≠ 0, respectively m is equal to x + n, where x = 2*mar n + 2, if y = 0: : for n = 1, we have mar n = 1, x = 4 and y = 0 so m = 5; : for n = 3, we have mar n = 3, x = 8 and y = 4 so m = 35; : for n = 5, we have mar n = 5, x = 12 and y = 8 so m = 101; : for n = 7, we have mar n = 7, x = 16 and y = 12 so m = 199; : for n = 9, we have mar n = 9, x = 20 and y = 16 so m = 329; : for n = 11, we have mar n = 2, x = 6 and y = 2 so m = 23; : for n = 13, we have mar n = 4, x = 10 and y = 6 so m = 73; : for n = 15, we have mar n = 6, x = 14 and y = 10 so m = 155; : for n = 17, we have mar n = 8, x = 18 and y = 14 so m = 269; : for n = 19, we have mar n = 1, x = 4 and y = 0 so m = 23; : for n = 21, we have mar n = 3, x = 8 and y = 4 so m = 53; : for n = 23, we have mar n = 5, x = 12 and -

MATHCOUNTS Bible Completed I. Squares and Square Roots: from 1

MATHCOUNTS Bible Completed I. Squares and square roots: From 12 to 302. Squares: 1 - 50 12 = 1 262 = 676 22 = 4 272 = 729 32 = 9 282 = 784 42 = 16 292 = 841 52 = 25 302 = 900 62 = 36 312 = 961 72 = 49 322 = 1024 82 = 64 332 = 1089 92 = 81 342 = 1156 102 = 100 352 = 1225 112 = 121 362 = 1296 122 = 144 372 = 1369 132 = 169 382 = 1444 142 = 196 392 = 1521 152 = 225 402 = 1600 162 = 256 412 = 1681 172 = 289 422 = 1764 182 = 324 432 = 1849 192 = 361 442 = 1936 202 = 400 452 = 2025 212 = 441 462 = 2116 222 = 484 472 = 2209 232 = 529 482 = 2304 242 = 576 492 = 2401 25 2 = 625 50 2 = 2500 II. Cubes and cubic roots: From 13 to 123. Cubes: 1 -15 13 = 1 63 = 216 113 = 1331 23 = 8 73 = 343 123 = 1728 33 = 27 83 = 512 133 = 2197 43 = 64 93 = 729 143 = 2744 53 = 125 103 = 1000 153 = 3375 III. Powers of 2: From 21 to 212. Powers of 2 and 3 21 = 2 31 = 3 22 = 4 32 = 9 23 = 8 33 = 27 24 = 16 34 = 81 25 = 32 35 = 243 26 = 64 36 = 729 27 = 128 37 = 2187 28 = 256 38 = 6561 29 = 512 39 = 19683 210 = 1024 310 = 59049 211 = 2048 311 = 177147 212 = 4096 312 = 531441 IV. Prime numbers from 2 to 109: It also helps to know the primes in the 100's, like 113, 127, 131, ... It's important to know not just the primes, but why 51, 87, 91, and others are not primes. -

Numbers 1 to 100

Numbers 1 to 100 PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 30 Nov 2010 02:36:24 UTC Contents Articles −1 (number) 1 0 (number) 3 1 (number) 12 2 (number) 17 3 (number) 23 4 (number) 32 5 (number) 42 6 (number) 50 7 (number) 58 8 (number) 73 9 (number) 77 10 (number) 82 11 (number) 88 12 (number) 94 13 (number) 102 14 (number) 107 15 (number) 111 16 (number) 114 17 (number) 118 18 (number) 124 19 (number) 127 20 (number) 132 21 (number) 136 22 (number) 140 23 (number) 144 24 (number) 148 25 (number) 152 26 (number) 155 27 (number) 158 28 (number) 162 29 (number) 165 30 (number) 168 31 (number) 172 32 (number) 175 33 (number) 179 34 (number) 182 35 (number) 185 36 (number) 188 37 (number) 191 38 (number) 193 39 (number) 196 40 (number) 199 41 (number) 204 42 (number) 207 43 (number) 214 44 (number) 217 45 (number) 220 46 (number) 222 47 (number) 225 48 (number) 229 49 (number) 232 50 (number) 235 51 (number) 238 52 (number) 241 53 (number) 243 54 (number) 246 55 (number) 248 56 (number) 251 57 (number) 255 58 (number) 258 59 (number) 260 60 (number) 263 61 (number) 267 62 (number) 270 63 (number) 272 64 (number) 274 66 (number) 277 67 (number) 280 68 (number) 282 69 (number) 284 70 (number) 286 71 (number) 289 72 (number) 292 73 (number) 296 74 (number) 298 75 (number) 301 77 (number) 302 78 (number) 305 79 (number) 307 80 (number) 309 81 (number) 311 82 (number) 313 83 (number) 315 84 (number) 318 85 (number) 320 86 (number) 323 87 (number) 326 88 (number) -

A Course in Mathematics Appreciation

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Theses and Dissertations 5-1-1995 A course in mathematics appreciation Daniel J. Kraft Rowan College of New Jersey Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd Part of the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Kraft, Daniel J., "A course in mathematics appreciation" (1995). Theses and Dissertations. 2256. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/2256 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COURSE IN MATHEMATICS APPRECATION by Daniel J. Kraft A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillent of the requirements of the Master of Arts Degree in the Craduate Division of Rowan College in Mathematics Educarion 1995 ''CC'~'"AnnmTrl hv J. Sooy tlntp A nnrnveA .h• Yw E AFM= f W ABSTRACT Daniel I. Kraft, A Course in Mathematics Appreciation, 1995, J. Sooy, Mathematics Education. The purpose of this study is to create a mini-corse in mathematics appreciation at the senior high school level. The mathematics appreciation course would be offered as an elective to students in the lth or 12th grade, who are concurrently enrolled in trigonometry or calculus. The topics covered in the mathematics appreciation course include: systems of numeration, congrunces, Diophantine equations, Fibonacci sequences, the golden section, imaginary numbers, the exponential function, pi, perfect numbers, numbers with shape, ciphers, magic squares, and root extraction techniques. In this study, the student is exposed to mathematical proofs, where appropriate, and is encouraged to create practice problems for other members of the class to solve.