ANTHROPOLOGY Chapter Showcase | 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12.3 MB PDF File

Restoring Paradise CSO Mediators Tackle Gang Violence in Belize Dignified Homecoming U.S. Leaders Honor Fallen state.gov/statemag Department Employees November 2012 Department Offices Engage Unique Audiences through Online and Alumni Connections November 2012 // Issue Number 572 09 Solemn Homecoming Honoring Fallen Colleagues Features 12 ‘A Lot of Joy’ Amb. Stevens’ Peace Corps Years 14 On Guard Still Former ‘Coasties’ Serve DOS 16 Equality, Security Women as Agents of Peace 18 Moment of Truce 16 CSO Trains Gang Mediators 20 Insider View Insights on Promotion Boards 22 Long Partnership ARS Builds U.S.-Africa Links 24 Port-au-Prince Rewarding Work in Haiti 30 IIP Challenge Posts Boost Social Media 32 Staying in Touch ECA Engages Exchange Alumni Columns 2 Post One 3 Inbox 18 4 In the News 7 Diversity Notes 8 Direct from the D.G. 36 Medical Report 37 Lying in State 38 In Brief 39 Retirements 40 Active Years 41 Obituaries 42 Appointments 44 End State 32 On the Cover Graphic illustration by David L. Johnston Post One BY ISAAC D. PACHECO Editor-in-Chief Isaac D. Pacheco // [email protected] Deputy Editor Leveraging Ed Warner // [email protected] Associate Editor Networks Bill Palmer // [email protected] In communication parlance, critical mass re- Art Director fers to the moment when a particular network David L. Johnston // [email protected] expands to the point that it becomes self-sus- taining, continuing to grow without needing Contacting Us additional external input. In sociological terms, 301 4th Street SW, Room 348 critical mass has also been referred to as the Washington DC 20547 tipping point, wherein an idea or movement [email protected] rapidly gains traction among a broad audience Phone: (202) 203-7115 following a period of gradual growth. -

Republic of Haiti

Coor din ates: 1 9 °00′N 7 2 °2 5 ′W Haiti Haiti (/ heɪti/ ( listen); French: Haïti [a.iti]; Haitian ˈ Republic of Haiti Creole: Ayiti [ajiti]), officially the Republic of Haiti (French: République d'Haïti; Haitian Creole: Repiblik République d'Haïti (French) [8] [note 1] Ayiti) and formerly called Hayti, is a Repiblik Ayiti (Haitian Creole) sovereign state located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea. It occupies the western three-eighths of the island, which it shares with the Dominican Republic.[11][12] Haiti is 27 ,7 50 square kilometres (10,7 14 sq mi) in Flag Coat of arms size and has an estimated 10.8 million people,[4] making it the most populous country in the Caribbean Motto: "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" (French)[1] Community (CARICOM) and the second-most "Libète, Egalite, Fratènite" (Haitian Creole) populous country in the Caribbean as a whole. The "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity" region was originally inhabited by the indigenous Motto on traditional coat of arms: Taíno people. Spain landed on the island on 5 "L'union fait la force" (French) [2] December 1492 during the first voyage of Christopher "Inite se fòs" (Haitian Creole) Columbus across the Atlantic. When Columbus "Union makes strength" initially landed in Haiti, he had thought he had found Anthem: La Dessalinienne (French) [13] India or China. On Christmas Day 1492, Columbus' Desalinyèn (Haitian Creole) flagship the Santa Maria ran aground north of what is "The Dessalines Song" 0:00 MENU now Limonade.[14][15][16][17] As a consequence, Columbus ordered his men to salvage what they could from the ship, and he created the first European settlement in the Americas, naming it La Navidad after the day the ship was destroyed. -

Vodou and the U.S. Counterculture

VODOU AND THE U.S. COUNTERCULTURE Christian Remse A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2013 Committee: Maisha Wester, Advisor Katerina Ruedi Ray Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Tori Ekstrand Dalton Jones © 2013 Christian Remse All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Maisha Wester, Advisor Considering the function of Vodou as subversive force against political, economic, social, and cultural injustice throughout the history of Haiti as well as the frequent transcultural exchange between the island nation and the U.S., this project applies an interpretative approach in order to examine how the contextualization of Haiti’s folk religion in the three most widespread forms of American popular culture texts – film, music, and literature – has ideologically informed the U.S. counterculture and its rebellious struggle for change between the turbulent era of the mid-1950s and the early 1970s. This particular period of the twentieth century is not only crucial to study since it presents the continuing conflict between the dominant white heteronormative society and subjugated minority cultures but, more importantly, because the Enlightenment’s libertarian ideal of individual freedom finally encouraged non-conformists of diverse backgrounds such as gender, race, and sexuality to take a collective stance against oppression. At the same time, it is important to stress that the cultural production of these popular texts emerged from and within the conditions of American culture rather than the native context of Haiti. Hence, Vodou in these American popular texts is subject to cultural appropriation, a paradigm that is broadly defined as the use of cultural practices and objects by members of another culture. -

MUSICIANS· ETUDE Tic [Eb on Choral Literature Yilu'~E Offices, Bryn Mawr', Pa

#n /ht/) #Joue ... .. Ability and Training Ezio Pinza "Your Musical Dawn Is at Hand" Boris Goldovsky Security for Music Teachers James Francis Cooke Midland Makes Its Own Music T. Gordon Harrington Gershwin Is Here to Stay Mario Braggiotti The Healthy Habit of Doubting Jan Smeterlin \ Ten Years at Tanglewood Ralph Berkowitz Who Are the World's Greatest Piano Teachers? Doron K. Antrim . LeTTeRS 1.' 0 1.' D E EDITOR Articles that it is. Dear Sir: I love your August Sybil Mac DOl/aid antatas and Oratorios issue. It alone is worth the price Memphis, Tenn; SATB Unleu Otherwise Indicated of a two-year subscription! Each article is stimulating, and after Class Instruction Dear Sir : For man y years, I reading them I have the same en- have been an interested reader and LENT thusiasm and stimulus that I have user of the ETUDE. I ha ve found ~ PENITENCE, PAROON AND PEACE (Advent and general,Sop. orI.., after attending a summer short I SOp Alto, Ten., Bar., Bar., 35 min.l Maunder 411401491.71 the articles recently have been ex- BEHOLD THE CHRIST (Holy Week or. genera Nevin ., 432-40168 $.75 course with an artist teacher. tremely stimulating. I also use the 40 rnin.) ....•...•......•.... Bass 20 min.) n PENITENCE PAROON AND PEACE (SSA, Sop., Alto, 35 mln.l Thanks so much! '" Maunder·Warhurst 411-40053.71 ETUDE La lend out to various ~ CALVARY ILent nr Easter, Ten., Bar., 'Sheppard 412-40061 .75 Mrs. C. P. Fishburne students, which they seem to enjoy 1 h ) Stainer 432·40128 .75 .n SEVEN LAST WOROS OF CHRIST (Sop., Ten., B!r., Eng.& la!.tert, 45'inl Walterboro, South Carolina CRUCIFIXION ITen., Bass, our 0 b rn 432.40L29 .60 § " OubOls·Douty411-401711~ immensely. -

Edible Oil Market in Haiti

Edible Oil Market in Haiti Prepared by Timothy T Schwartz with assistance from Rigaud Charles December 22, 2009 Monetization Marketing ACDI/VOCA PL-480 Title II Multi-Year Assistance Program - Haiti ACDI/VOCA/Schwartz Edible Oil Table of contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………... 1 2. Consumption of Edible Oils …………………………………… 3 3. Preferred Type of Oil…………………………………………… 5 4. Sources of Edible Oils………………………………………….. 6 5. Quantity of Oil Imported……………………………………….. 7 6. Distribution……………………………………………………... 14 7. Costs and Profits………………………………………………... 17 8. Recovery………………………………………………………... 19 9. Recommendations………………………………………………. 21 Annex A. Contacts and People Interviewed………………………... 22 A1. Contacts and People Interviewed…………………………... 22 A2. Institutional Contacts………………………………………. 22 A3. List of distributors……………………………………......... 23 A4. Letter to Missionaries………………………………………. 24 A5: Responses to Email to Missionaries……………………...... 25 Annex B: Publicity/Marketing Company…………………………... 29 B1. Company: Mediacom…………………………………......... 29 B2. Costs………………………………………………………... 30 B3. Flier for Redistributors and Merchants…………………….. 31 Bibliography………………………………………………………… 32 Notes………………………………………………………………… 33 i ACDI/VOCA/Schwartz Edible Oil Charts Chart 1.1: Price of Edible Oil by Price of Petroleum…………………………... 1 Chart 5.1: Types of Oil Imported………………………………………………. 7 Chart 5.2: Oil Importers Market……………………………………………….. 7 Chart 5.3: Cost of Soy Compared to Palm Oil………………………………… 7 Chart 5.4: Percentage More in Cost of Soy over Palm Oil……………………. 8 Chart 5.5: Types of Edible Oils Imported into APN by Year…………………. 8 Chart 5.6: Origin of Edible Oil by Year………………………………………… 9 Table 6.1: Total Oil Imported Based on Estimated Per Capita Daily 11 Consumption of Calories from Fat……………………………………………… Chart 6.2: Registered vs. Missing Edible Oil…………………………………… 11 Chart 6.5: Comparison: Data from Bailey (2006) to Recent AGD Data (2009)... 12 Chart 6.4: Reported Oil Imports and Time Line for Changing Governments…. -

Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy

Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy A Journey Through Time A Resource Guide for Teachers HABETAC The Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center HABETAC The Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center @ Brooklyn College 2900 Bedford Avenue James Hall, Room 3103J Brooklyn, NY 11210 Copyright © 2005 Teachers and educators, please feel free to make copies as needed to use with your students in class. Please contact HABETAC at 718-951-4668 to obtain copies of this publication. Funded by the New York State Education Department Acknowledgments Haitian Historical and Cultural Legacy: A Journey Through Time is for teachers of grades K through 12. The idea of this book was initiated by the Haitian Bilingual/ESL Technical Assistance Center (HABETAC) at City College under the direction of Myriam C. Augustin, the former director of HABETAC. This is the realization of the following team of committed, knowledgeable, and creative writers, researchers, activity developers, artists, and editors: Marie José Bernard, Resource Specialist, HABETAC at City College, New York, NY Menes Dejoie, School Psychologist, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Yves Raymond, Bilingual Coordinator, Erasmus Hall High School for Science and Math, Brooklyn, NY Marie Lily Cerat, Writing Specialist, P.S. 181, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Christine Etienne, Bilingual Staff Developer, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Amidor Almonord, Bilingual Teacher, P.S. 189, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Peter Kondrat, Educational Consultant and Freelance Writer, Brooklyn, NY Alix Ambroise, Jr., Social Studies Teacher, P.S. 138, CSD 17, Brooklyn, NY Professor Jean Y. Plaisir, Assistant Professor, Department of Childhood Education, City College of New York, New York, NY Claudette Laurent, Administrative Assistant, HABETAC at City College, New York, NY Christian Lemoine, Graphic Artist, HLH Panoramic, New York, NY. -

Newsletter 2Nd Quarter 2012 English

IN THE ZONE nd Newsletter #4, 2 quarter 2012 “IN THE ZONE” a tribute to the Sustainable Tourism Zone of the Greater Caribbean. EDITORIAL Welcome to the fourth edition of “IN THE ZONE”, which we have endearingly dubbed, “IN OUR KITCHEN”. The Wider Caribbean is truly a unique destination. As a collective of almost 30 Member States there is so much to explore. From breath-taking mountain ranges, to white, pink or black sandy beaches or the adventurous nature trails, it is recognized that the Region’s offerings are plenty. It is also unanimously agreed that in addition to the scenic beauty and hospitality experienced; the most enticing treasures are the many exquisite culinary delights. Whether it be a “Bake and Shark” at Maracas Bay in Trinidad and Tobago, a “Javaanse Rijstafel” in Suriname, Dominican “Mofongo” , a “Reina Pepiada” in Venezuela, or Salvadorian “Pupusas” accompanied by either some Blue Mountain Jamaican Coffee or a Cocktail of Curacao Blue or even a nicely aged Rhum Clément of Martinique, we all keep coming back for more. Sharing our national dishes and beverages provides the opportunity to share a part of our rich heritage. This one tourism product allows for a genuine interaction between the local community that produces, prepares and presents the fruits of the land and the tourists who sit at our tables and enjoy the offerings. Hence, the potential of securing return visits through gastronomic tourism should not be When in St. Lucia you have to underestimated. visit Anse La Raye "Seafood Friday" held every Friday This edition of “IN THE ZONE”, invites you into the kitchens of the Greater Caribbean, with various delightful contributions from Mexico, Haiti, Venezuela, night. -

Barbara Shelton Cultural Semester Project the Music A

Emily Wayman Music 1040 Music & Culture Instructor: Barbara Shelton Cultural Semester Project The Music and Culture of Haiti Most people only know about the country of Haiti because of the disastrous earthquake that struck in 2010. However, Haiti is a country that has overcome many struggles, natural and political. Besides becoming the world's first independent black republic, it has developed a rich culture that reaches deep into the arts. Its music has influenced musical styles across the Caribbean and has gained huge popularity in the southeastern United States. Haiti makes up about one third of the island Hispaniola in the Caribbean, while the rest of the island consists of the Dominican Republic. Originally the entire island was claimed by the Spanish, but in 1697 the part that became SaintDomingue was released to the French, in the Treaty of Ryswik.1 While under French control, the entire purpose of the colony was to produce commodities such as coffee and sugar on plantations. Thousands of African slaves were brought across the sea to work these plantations, and soon the slaves outnumbered the white settlers four to one.2 This imbalance in numbers eventually led to slave revolts, and on January 1, 1804, Haiti became the world's first independent black republic. Since its foundation, the government of Haiti has struggled. Leaders come and go through assassinations and military and civil coups at an alarming rate. In just the seventytwo year period between 1843 and 1915 Haiti was ruled by twentytwo different leaders. Only one of 1 Haitian Pearl, “History of Haiti: Parts 13” 2012. -

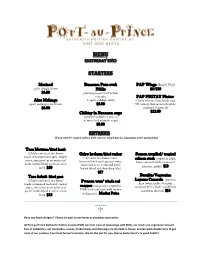

Starters Entrees

Menu (Saturday eve) Starters Marinad Bannann Peze avek PAP Wings (6ct)/(10ct) (spicy dough fritter) Pikliz $6/$10 $6.00 (double pressed fried yellow plantain PAP FRITAY Platter: Akra Malanga w/spicy cabbage slaw) Choice of meat (fried lamb, goat (spicy malanga root fritter) $5.00 OR turkey), bannann avek pikliz, $6.00 marinad, & patat fri Chiktay in Bannann cups $22.00 (stir fried codfish or aran sò in mini fried plantain cups) $8.00 Entrees (Each entrée comes with a side of rice, salad kay la, bannann peze and pikliz) Taso Mouton/fried lamb (Halal) marinated in a house Griyo kodenn/fried turkey Somon tropikal/ tropical made, fermented and aged, pepper marinated in a house made, salmon steak steeped in DBK sauce, simmered in an onion and fermented and aged, pepper sauce, herb marinade with onions and garlic herbal blend and then deep simmered in an onion and garlic peppers, grilled $18 fried $20 herbal blend and then deep fried $17 Taso kabrit/fried goat Berejèn/Vegetarian Legume Casserole, eggplant, (Halal) marinated in a house Pwason woz/ whole red made, fermented and aged, pepper lima beans, garlic, & onion, snapper pan sautéed steeped in sauce, simmered in an onion and seasoned with a fresh herb blend, DBK herb marinade with onions garlic herbal blend and then deep sautéed in olive oil $14 and peppers Market Price fried $22 Have any food allergies? Please let your server know as you place your order. At Port-au-Prince Authentic Haitian Cuisine (PAP) we steer clear of seasonings with MSG, our meats are vegetarian fed and free of antibiotics, our marinades, sauces, herbal mixes and dressings are all made in house, and we work double time to get most of our produce from local farmer’s markets. -

Ethnic American Cooking I Ftecip.E F.0.Ft Uvlng Ln ANEW WO:Ftld

Ethnic American Cooking I ftECIP.E F.0.ft UVlNG lN ANEW WO:ftLD Edited by LUCY M. LONG - Ethnic American Cooking Recipes for Living in a New World Edited by Lucy M. Long ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham• Boulder• New York• London • Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SEl l 4AB Copyright© 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield All rights reserved. o pare of this book may be reproduced in any for m or by any electronic r mechanical mean , in luding information storage and recri val systems, without written permi ion from th publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote pa ages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Long, Lucy M., 1956- author. Title: Ethnic American cooking: rec ipes for living in a new world/ Lucy M. Long. Description: Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc., (2016] \ Includes bibliographical references and index. Id entifier: LCCN 2016006179 (print) \ LCCN 2016013468 (ebook) \ ISBN 9781442267336 (cloth: alk. paper) \ I BN 978I442267343 (Electronic) ubje t : LCSH: International cooking. \ Cooking--United State . \ Echnicity. \ L Ff: Cookbook . Classification: LCC TX725.Al L646 2016 (print) \ LCC TX725.Al (ebook) \ DDC 64 l.50973--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016006179 TM The paper u ed in thi publication me ts the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science - Permanence of Paper fo r Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NI 0 Z 9.48-1992. -

The Depreciation of Haitian Creole and Haitian Code Switching

The depreciation of haitian creole and haitian code switching La depreciación del creole haitiano y el cambio de código haitiano Patrick Pierre1 Recepción: 06 de agosto de 2020 Aceptación: 15 de octubre de 2020 1 Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas (ESPE), Quito, Ecuador. [email protected] REVISTA PUCE. ISSN: 2528-8156. NÚM. 111 3 NOVIEMBRE DE 2020 - 3 MAYO DE 2021, PATRICK PIERRE, PP. 71-91 The depreciation of haitian creole and haitian code switching La depreciación del creole haitiano y el cambio de código haitiano patrick Pierre Key words: Creole language, Haitian Creole, Lexifier, Code-switch, Depreciation. Palabras clave: Idioma Creole, Creole haitiano, Lexificador, Cambio de código, Depreciación. Abstract The purpose of this paper is to dominance, it was the language of the give an overview of Haitian code-switch- plantations’ masters. These two lan- ing as a diglossic country and Haitian guages have remained the official lan- Creole depreciation as the native lan- guages of Haiti in which Haitian people guage of Haiti. The history of the Hai- Code-switch when using either French tian Creole language developed by or Haitian Creole. However, Creole has enslaved west African in the plantation become the language of depreciation, in of the Island, during the slave rebellion another term a marginalized language. for the revolution after several attempts In this study a qualitative and descriptive conspiring for their freedom. After the analysis have been carried out through embarkation of the French Colony in social medias such as Instagram, Twitter, the Island to settle from 1659 till 1804, Facebook and You-Tube to collect data French has become the language of on Haitian code-switching by observ- 73 THE DEPRECIATION OF HAITIAN CREOLE AND HAITIAN CODE SWITCHING ing one of the Haitian Ex-presidents, Mr. -

Haitian Culture Curriculum Guide Grades K-5

The School Board of Broward County, Florida Benjamin J. Williams, Chair Beverly A. Gallagher, Vice Chair Carole L. Andrews Robin Bartleman Darla L. Carter Maureen S. Dinnen Stephanie Arma Kraft, Esq. Robert D. Parks, Ed.D. Marty Rubinstein Dr. Frank Till Superintendent of Schools The School Board of Broward County, Florida, prohibits any policy or procedure which results in discrimination on the basis of age, color, disability, gender, national origin, marital status, race, religion or sexual orientation. Individuals who wish to file a discrimination and/or harassment complaint may call the Director of Equal Educational Opportunities at (754) 321-2150 or Teletype Machine TTY (754) 321-2158. Individuals with disabilities requesting accommodations under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) may call Equal Educational Opportunities (EEO) at (754) 321-2150 or Teletype Machine TTY (754) 321-2158. www.browardschools.com Haitian Culture Curriculum Guide Grades K-5 Dr. Earlean C. Smiley Deputy Superintendent Curriculum and Instruction/Student Support Sayra Velez Hughes Executive Director Multicultural & ESOL Program Services Education Elizabeth L. Watts, Ph.D. Multicultural Curriculum Development/Training Specialist Multicultural Department Broward County Public Schools ACKNOWLEDGMENT Our sincere appreciation is given to Mrs. Margaret M. Armand, Bilingual Education Consultant, for granting us permission to use her Haitian oil painting by Francoise Jean entitled, "Children Playing with Kites” for the cover of the Haitian Culture Curriculum Guide Grades K-5. She has also been kind enough to grant us permission to use artwork from her private collection which have been made into slides for this guide. TABLE OF CONTENTS Writing Team................................................................................................................................. i Introduction ..................................................................................................................................