Jacob Kirk Ichthyology 4453 Literature Review of the Chain Pickerel Esox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Go Fish! Lesson Plan

NYSDEC Region 1 Freshwater Fisheries I FISH NY Program Go Fish! Grade Level(s): 3-5 NYS Learning Standards Time: 30 - 45 minutes Core Curriculum MST Group Size: 20-35 Standard 4: Living Environment Students will: understand and apply scientific Summary concepts, principles, and theories pertaining to This lesson introduces students to the fish the physical setting and living environment and families indigenous to New York State by recognize the historical development of ideas in playing I FISH NY’s card game, “Go science. Fish”. Students will also learn about the • Key Idea 1: Living things are both classification system and the external similar to and different from each other anatomy features of fish. and nonliving things. Objectives • Key Idea 2: Organisms inherit genetic • Students will be able to identify information in a variety of ways that basic external anatomy of fish and result in continuity of structure and the function of each part function between parents and offspring. • Students will be able to explain • Key Idea 3: Individual organisms and why it is important to be able to species change over time. tell fish apart • Students will be able to name several different families of fish indigenous to New York Materials • Freshwater or Saltwater Fish models/picture • Lemon Fish worksheet • I FISH NY Go Fish cards Vocabulary • Anal Fin- last bottom fin on a fish located near the anal opening; used in balance and steering • Caudal/Tail Fin- fin on end of fish; used to propel the fish • Dorsal Fin- top or backside fin on a fish; -

Ecology and Conservation of Mudminnow Species Worldwide

FEATURE Ecology and Conservation of Mudminnow Species Worldwide Lauren M. Kuehne Ecología y conservación a nivel mundial School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195 de los lucios RESUMEN: en este trabajo, se revisa y resume la ecología Julian D. Olden y estado de conservación del grupo de peces comúnmente School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, Box conocido como “lucios” (anteriormente conocidos como 355020, Seattle, WA 98195, and Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith Uni- la familia Umbridae, pero recientemente reclasificados en versity, QLD, 4111, Australia. E-mail: [email protected] la Esocidae) los cuales se constituyen de sólo cinco espe- cies distribuidas en tres continentes. Estos peces de cuerpo ABSTRACT: We review and summarize the ecology and con- pequeño —que viven en hábitats de agua dulce y presentan servation status of the group of fishes commonly known as movilidad limitada— suelen presentar poblaciones aisla- “mudminnows” (formerly known as the family Umbridae but das a lo largo de distintos paisajes y son sujetos a las típi- recently reclassified as Esocidae), consisting of only five species cas amenazas que enfrentan las especies endémicas que distributed on three continents. These small-bodied fish—resid- se encuentran en contacto directo con los impactos antro- ing in freshwater habitats and exhibiting limited mobility—often pogénicos como la contaminación, alteración de hábitat occur in isolated populations across landscapes and are subject e introducción de especies no nativas. Aquí se resume el to conservation threats common to highly endemic species in conocimiento actual acerca de la distribución, relaciones close contact with anthropogenic impacts, such as pollution, filogenéticas, ecología y estado de conservación de cada habitat alteration, and nonnative species introductions. -

Fish Species of Saskatchewan

Introduction From the shallow, nutrient -rich potholes of the prairies to the clear, cool rock -lined waters of our province’s north, Saskatchewan can boast over 50,000 fish-bearing bodies of water. Indeed, water accounts for about one-eighth, or 80,000 square kilometers, of this province’s total surface area. As numerous and varied as these waterbodies are, so too are the types of fish that inhabit them. In total, Saskatchewan is home to 67 different fish species from 16 separate taxonomic families. Of these 67, 58 are native to Saskatchewan while the remaining nine represent species that have either been introduced to our waters or have naturally extended their range into the province. Approximately one-third of the fish species found within Saskatchewan can be classed as sportfish. These are the fish commonly sought out by anglers and are the best known. The remaining two-thirds can be grouped as minnow or rough-fish species. The focus of this booklet is primarily on the sportfish of Saskatchewan, but it also includes information about several rough-fish species as well. Descriptions provide information regarding the appearance of particular fish as well as habitat preferences and spawning and feeding behaviours. The individual species range maps are subject to change due to natural range extensions and recessions or because of changes in fisheries management. "...I shall stay him no longer than to wish him a rainy evening to read this following Discourse; and that, if he be an honest Angler, the east wind may never blow when he goes a -fishing." The Compleat Angler Izaak Walton, 1593-1683 This booklet was originally published by the Saskatchewan Watershed Authority with funds generated from the sale of angling licences and made available through the FISH AND WILDLIFE DEVELOPMENT FUND. -

Wild Rhode Island

Volume 6, 6, Issue Issue 3 3 Summer/Summer/ Fall Fall 2013 WildWild Rhode Rhode Island Island 2013 A Quarterly Publication from the Division of Fish and Wildlife, RI Department of Environmental Management Inland Fishes of RI available for purchase at DEM ! The Inland Fishes of Rhode Island, by Alan Libby and Illustrations by Robert Jon Golder, are now available at the DEM Office of Boating and Licensing. This 278 page publication published by the Division of Fish and Wildlife describes more than 70 fishes found in fresh and brackish waters in Rhode Island. Filled with beautiful color and black and white scientific illustrations, each fish is addressed with a detailed description and color location map. Included are the variety of freshwater habitats found in Rhode Island along with the methodology used to carry out the field work that has led to this publication. Alan D. Libby is a principal freshwater biologist and has worked for the DEM’s Division of Fish and Wildlife for over 26 years. This definitive work is the culmination of 15 years of surveying the inland fishes of the state. Alan surveyed over 377 pond and stream locations throughout Rhode Island, many of which were sampled multiple times over the years. The Inland Fishes of Rhode Island is available in an 8” x 10” paper- back. The cost is $26.75 including tax, and may be purchased using a credit card, cash, check or money order from the Providence Licensing Office at 235 Promenade Street. Additionally the book may be mail- ordered. Please see the DEM website for more information at: www.dem.ri.gov New England Cottontail Rabbits – a Rare Species Returns Inside this issue: to Narragansett Bay Islands by Brian C. -

Northern Pike Esox Lucius ILLINOIS RANGE

northern pike Esox lucius Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The northern pike's average life span is eight to 10 Class: Osteichthyes years. The average weight is two pounds. It may Order: Esociformes attain a maximum length of 53 inches. The fins are rounded, and all except the pectoral fins have dark Family: Esocidae spots. Scales are present on the cheek and half of ILLINOIS STATUS the gill cover. The eyes are yellow. The long, green body has yellow spots on the sides. The belly is common, native white to dark yellow. The duckbill-shaped snout is easily seen. BEHAVIORS The northern pike lives in lakes, rivers and marshes. It prefers water without strong currents and with many plants. This fish reaches maturity at age two to three years. Spawning occurs in March. The female deposits up to 150,000 eggs that are scattered in marshy areas or other shallow water areas. Eggs hatch in 12-14 days. This fish eats fishes, insects, crayfish, frogs and reptiles. ILLINOIS RANGE © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. close up of head close up of side © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. © Engbretson Underwater Photography adult Aquatic Habitats lakes, ponds and reservoirs; rivers and streams; marshes Woodland Habitats none Prairie and Edge Habitats none © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources.. -

Fisheries Full Issue PDF Volume 39, Issue 3

This article was downloaded by: [American Fisheries Society] On: 24 March 2014, At: 13:30 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Fisheries Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ufsh20 Full Issue PDF Volume 39, Issue 3 Published online: 21 Mar 2014. To cite this article: (2014) Full Issue PDF Volume 39, Issue 3, Fisheries, 39:3, 97-144, DOI: 10.1080/03632415.2014.902705 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03632415.2014.902705 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. -

APPENDIX M Common and Scientific Species Names

Bay du Nord Development Project Environmental Impact Statement APPENDIX M Common and Scientific Species Names Bay du Nord Development Project Environmental Impact Statement Common and Species Names Common Name Scientific Name Fish Abyssal Skate Bathyraja abyssicola Acadian Redfish Sebastes fasciatus Albacore Tuna Thunnus alalunga Alewife (or Gaspereau) Alosa pseudoharengus Alfonsino Beryx decadactylus American Eel Anguilla rostrata American Plaice Hippoglossoides platessoides American Shad Alosa sapidissima Anchovy Engraulidae (F) Arctic Char (or Charr) Salvelinus alpinus Arctic Cod Boreogadus saida Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Thunnus thynnus Atlantic Cod Gadus morhua Atlantic Halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus Atlantic Mackerel Scomber scombrus Atlantic Salmon (landlocked: Ouananiche) Salmo salar Atlantic Saury Scomberesox saurus Atlantic Silverside Menidia menidia Atlantic Sturgeon Acipenser oxyrhynchus oxyrhynchus Atlantic Wreckfish Polyprion americanus Barndoor Skate Dipturus laevis Basking Shark Cetorhinus maximus Bigeye Tuna Thunnus obesus Black Dogfish Centroscyllium fabricii Blue Hake Antimora rostrata Blue Marlin Makaira nigricans Blue Runner Caranx crysos Blue Shark Prionace glauca Blueback Herring Alosa aestivalis Boa Dragonfish Stomias boa ferox Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis Brown Bullhead Catfish Ameiurus nebulosus Burbot Lota lota Capelin Mallotus villosus Cardinal Fish Apogonidae (F) Chain Pickerel Esox niger Common Grenadier Nezumia bairdii Common Lumpfish Cyclopterus lumpus Common Thresher Shark Alopias vulpinus Crucian Carp -

Esox Lucius) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Northern Pike (Esox lucius) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, February 2019 Web Version, 8/26/2019 Photo: Ryan Hagerty/USFWS. Public Domain – Government Work. Available: https://digitalmedia.fws.gov/digital/collection/natdiglib/id/26990/rec/22. (February 1, 2019). 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Froese and Pauly (2019a): “Circumpolar in fresh water. North America: Atlantic, Arctic, Pacific, Great Lakes, and Mississippi River basins from Labrador to Alaska and south to Pennsylvania and Nebraska, USA [Page and Burr 2011]. Eurasia: Caspian, Black, Baltic, White, Barents, Arctic, North and Aral Seas and Atlantic basins, southwest to Adour drainage; Mediterranean basin in Rhône drainage and northern Italy. Widely distributed in central Asia and Siberia easward [sic] to Anadyr drainage (Bering Sea basin). Historically absent from Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean France, central Italy, southern and western Greece, eastern Adriatic basin, Iceland, western Norway and northern Scotland.” Froese and Pauly (2019a) list Esox lucius as native in Armenia, Azerbaijan, China, Georgia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bosnia Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Moldova, Monaco, 1 Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Ukraine, Canada, and the United States (including Alaska). From Froese and Pauly (2019a): “Occurs in Erqishi river and Ulungur lake [in China].” “Known from the Selenge drainage [in Mongolia] [Kottelat 2006].” “[In Turkey:] Known from the European Black Sea watersheds, Anatolian Black Sea watersheds, Central and Western Anatolian lake watersheds, and Gulf watersheds (Firat Nehri, Dicle Nehri). -

Current Knowledge on the European Mudminnow, Umbra Krameri Walbaum, 1792 (Pisces: Umbridae)

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien Jahr/Year: 1995 Band/Volume: 97B Autor(en)/Author(s): Wanzenböck Josef Artikel/Article: Current knowledge on the European mudminnow, Umbra krameri Walbaum, 1792 (Pisces: Umbridae). 439-449 ©Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 97 B 439 - 449 Wien, November 1995 Current knowledge on the European mudminnow, Umbra krameri WALBAUM, 1792 (Pisces: Umbridae) J. Wanzenböck* Abstract The present paper summarizes the current knowledge on the European mudminnow {Umbra krameri WALBAUM, 1792) with respect to systematics, taxonomy, and ecology. Key words: Umbridae, Umbra krameri, systematics, taxonomy, ecology. Zusammenfassung Die vorliegende Arbeit faßt den derzeitigen Wissensstand über den Europäischen Hundsfisch {Umbra kra- meri WALBAUM, 1792) unter Berücksichtigung systematischer, taxonomischer und ökologischer Aspekte zusammen. Names, taxonomy, and systematics Scientific name: Umbra krameri WALBAUM, 1792 Common names: Based on BLANC & al. (1971) and LINDBERG & HEARD (1972). Names suggested by the author are given at first, those marked with an asterix (*) are given in BLANC & al. (1971). German: Europäischer Hundsfisch, Hundsfisch*, Ungarischer Hundsfisch Hungarian: Lâpi póc* Czech: Tmavec hnëdy*, Blatnâk tmavy Slovak: Blatniak* Russian: Evdoshka, Umbra* Ukrainian: Boboshka (Dniestr), Evdoshka, Lezheboka -

Little Pee Dee-Lumber Focus Area Conservation Plan

Little Pee Dee-Lumber Focus Area Conservation Plan South Carolina Department of Natural Resources February 2017 Little Pee Dee-Lumber Focus Area Conservation Plan Prepared by Lorianne Riggin and Bob Perry1, and Dr. Scott Howard2 February 2017 Acknowledgements The preparers thank the following South Carolina Department of Natural Resources staff for their special expertise and contributions toward the completion of this report: Heritage Trust data base manager Julie Holling; GIS applications manager Tyler Brown for mapping and listing of protected properties; archeologist Sean Taylor for information on cultural resources; fisheries biologists Kevin Kubach, Jason Marsik, and Robert Stroud for information regarding aquatic resources; hydrologist Andy Wachob for information on hydrologic resources; and wildlife biologists James Fowler, Dean Harrigal, Sam Stokes, Jr. and Amy Tegler for information regarding wildlife resources. 1 South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Office of Environmental Programs. 2 South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Geological Survey. i Little Pee Dee-Lumber Focus Area Conservation Plan The goal of this conservation plan is to provide science-based guidance for future decisions to protect natural resource, riparian corridors and traditional landscape uses such as fish and wildlife management, hunting, fishing, agriculture and forestry. Such planning is valuable in the context of protecting Waters of the United States in accordance with the Clean Water Act, particularly when the interests of economic development and protection of natural and cultural resources collide. Such planning is vital in the absence of specific watershed planning. As additional information is gathered by the focus area partners, and as further landscape-scale conservation goals are achieved, this plan will be updated accordingly. -

Redfin Pickerel

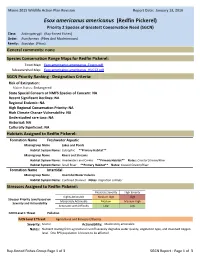

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Esox americanus americanus (Redfin Pickerel) Priority 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Actinopterygii (Ray-finned Fishes) Order: Esociformes (Pikes And Mudminnows) Family: Esocidae (Pikes) General comments: none Species Conservation Range Maps for Redfin Pickerel: Town Map: Esox americanus americanus_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Esox americanus americanus_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: Maine Status: Endangered State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: NA High Climate Change Vulnerability: NA Understudied rare taxa: NA Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Redfin Pickerel: Formation Name Freshwater Aquatic Macrogroup Name Lakes and Ponds Habitat System Name: Eutrophic **Primary Habitat** Macrogroup Name Rivers and Streams Habitat System Name: Headwaters and Creeks **Primary Habitat** Notes: Coastal Stream/River Habitat System Name: Small River **Primary Habitat** Notes: Coastal Stream/River Formation Name Intertidal Macrogroup Name Intertidal Water Column Habitat System Name: Confined Channel Notes: migration corridor Stressors Assigned to Redfin Pickerel: Moderate Severity High Severity Highly Actionable Medium-High High Stressor Priority Level based on Moderately Actionable Medium Medium-High Severity and Actionability Actionable with Difficulty Low Low IUCN Level 1 Threat Pollution -

A Review of Hooking Mortality, Associated Influential Factors, and Angling Gear Restrictions, with Implications for Management of the Alligator Gar

A Review of Hooking Mortality, Associated Influential Factors, and Angling Gear Restrictions, with Implications for Management of the Alligator Gar by Daniel J. Daugherty and Daniel L. Bennett Management Data Series No. 297 2019 INLAND FISHERIES DIVISION 4200 Smith School Road Austin, Texas 78744 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) is dedicated to the conservation and management of quality fisheries for the Alligator Gar Atractosteus spatula. To further inform science-based management decisions and identify knowledge gaps, we conducted a review of information concerning hooking mortality in catch-and-release fisheries, as well as gear-based regulations and best management practices (BMPs) in place to minimize its occurrence. Given the historic paucity of research on the Alligator Gar, no direct study of hooking mortality has been conducted. Thus, evaluations for species of similar form and function, as well as general information on hooking mortality in fishes, were reviewed to gain inferences on the potential significance of this mortality source within the context of Alligator Gar fisheries. Hooking mortality of other large-bodied top predators was generally less than 10%; deep hooking was the primary contributor to post-release mortality. Among 274 hooking mortality studies reviewed for various species, hooking mortality rates were positively skewed (median = 11%, mean = 18%). Anatomical hooking location was again the most significant factor influencing mortality. No states have implemented gear-based restrictions for Alligator Gar; however, restrictions on hook type for species exhibiting similar life-history or anatomical features (e.g., pikes Esox spp. and sturgeons Acipenser spp.) have been used to reduce the likelihood of deep hooking.