Flood Risk from Groundwater: Examples from a Chalk Catchment in 2 Southern England 3 4 A.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 5 Defining Reference Conditions for Chalk Stream and Fenland Natural Channels

Appendix 5 Defining reference conditions for chalk stream and Fenland natural channels Chalk stream geomorphology is poorly understood, and under-researched. What studies exist appear to confirm that the majority of UK and European chalk streams have been modified in form and hydraulics by a long history of river management (Sear and others 1999, WRc 2000). The overriding control these modifications exert on the geomorphology and processes operating within the channel, make it difficult to establish what features and physical habitat diversity a natural, unmodified chalk stream should display. In the absence of semi-natural chalk stream habitats from which reference conditions can be determined, the Water Framework Directive specifies the use of palaeoecological information (Logan and Furze 2002). However much of this research is focussed on interpretations of human activity or climatic reconstruction rather than on the specific determination of river form and associated habitats (Davies and Griffiths 2005; French and Lewis 2002). Despite this, it is possible to reconstruct some information of relevance to characterising the floodplain habitats associated with relatively undisturbed chalk streams and rivers. French and others 2005 report a complex suite of landscape changes in the Dry valley and upper reaches of a chalk stream in Dorset. Their results suggest the presence of a relatively wide shallow low sinuosity meandering channel throughout the Holocene into the early historic period, between 30 - 50m in width and 1.5 – 3m in depth with a width:depth ratio of between 10 and 33. The authors stress that the development of each chalk valley is best considered individually rather than to expect a common history of landscape evolution hence the precise form of the channel system and floodplain habitats is also likely to be valley specific. -

The Natural Capital of Temporary Rivers: Characterising the Value of Dynamic Aquatic–Terrestrial Habitats

VNP12 The Natural Capital of Temporary Rivers: Characterising the value of dynamic aquatic–terrestrial habitats. Valuing Nature | Natural Capital Synthesis Report Lead author: Rachel Stubbington Contributing authors: Judy England, Mike Acreman, Paul J. Wood, Chris Westwood, Phil Boon, Chris Mainstone, Craig Macadam, Adam Bates, Andy House, Dídac Jorda-Capdevila http://valuing-nature.net/TemporaryRiverNC Suggested citation: Stubbington, R., England, J., Acreman, M., Wood, P.J., Westwood, C., Boon, P., The Natural Capital of Mainstone, C., Macadam, C., Bates, A., House, A, Didac, J. (2018) The Natural Capital of Temporary Temporary Rivers: Rivers: Characterising the value of dynamic aquatic- terrestrial habitats. Valuing Nature Natural Capital Characterising the value of dynamic Synthesis Report VNP12. The text is available under the Creative Commons aquatic–terrestrial habitats. Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-SA 4.0) Valuing Nature | Natural Capital Synthesis Report Contents Introduction: Services provided by wet and the natural capital of temporary rivers.............. 4 dry-phase assets in temporary rivers................33 What are temporary rivers?...................................... 4 The evidence that temporary rivers deliver … services during dry phases...................34 Temporary rivers in the UK..................................... 4 Provisioning services...................................34 The natural capital approach Regulating services.......................................35 to ecosystem protection............................................ -

River Restoration and Chalk Streams

River Restoration and Chalk Streams Monday 22nd – Tuesday 23rd January 2001 University of Hertfordshire, College Lane, Hatfield AL10 9AB Organised by the River Restoration Centre in partnership with University of Hertfordshire Environment Agency, Thames Region Report compiled by: Vyv Wood-Gee Countryside Management Consultant Scabgill, Braehead, Lanark ML11 8HA Tel: 01555 870530 Fax: 01555 870050 E-mail: [email protected] Mobile: 07711 307980 ____________________________________________________________________________ River Restoration and Chalk Streams Page 1 Seminar Proceedings CONTENTS Page no. Introduction 3 Discussion Session 1: Flow Restoration 4 Discussion Session 2: Habitat Restoration 7 Discussion Session 3: Scheme Selection 9 Discussion Session 4: Post Project Appraisal 15 Discussion Session 5: Project Practicalities 17 Discussion Session 6: BAPs, Research and Development 21 Discussion Session 7: Resource Management 23 Discussion Session 8: Chalk streams and wetlands 25 Discussion Session 9: Conclusions and information dissemination 27 Site visit notes 29 Appendix I: Delegate list 35 Appendix II: Feedback 36 Appendix III: RRC Project Information Pro-forma 38 Appendix IV: Project summaries and contact details – listed 41 alphabetically by project name. ____________________________________________________________________________ River Restoration and Chalk Streams Page 2 Seminar Proceedings INTRODUCTION Workshop Objectives · To facilitate and encourage interchange of information, views and experiences between people working with projects and programmes with strong links to chalk streams and activities or research that affect this environment. · To improve the knowledge base on the practicalities and associated benefits of chalk stream restoration work in order to make future investments more cost effective. Participants The workshop was specifically targeted at individuals and organisations whose activities, research or interests include a specific practical focus on chalk streams. -

The State of England's Chalk Streams

FUNDED WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM REPORT UK 2014 The State of England’s Chalk Streams This report has been written by Rose O’Neill and Kathy Hughes on behalf of WWF-UK with CONTENTS help and assistance from many of the people and organisations hard at work championing England’s chalk streams. In particular the authors would EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 like to thank Charles Rangeley-Wilson, Lawrence Talks, Sarah Smith, Mike Dobson, Colin Fenn, 8 Chris Mainstone, Chris Catling, Mike Acreman, FOREWORD Paul Quinn, David Bradley, Dave Tickner, Belinda by Charles Rangeley-Wilson Fletcher, Dominic Gogol, Conor Linsted, Caroline Juby, Allen Beechey, Haydon Bailey, Liz Lowe, INTRODUCTION 13 Bella Davies, David Cheek, Charlie Bell, Dave Stimpson, Ellie Powers, Mark Gallant, Meyrick THE STATE OF ENGLAND’S CHALK STREAMS 2014 19 Gough, Janina Gray, Ali Morse, Paul Jennings, Ken Caustin, David Le Neve Foster, Shaun Leonard, Ecological health of chalk streams 20 Alex Inman and Fran Southgate. This is a WWF- Protected chalk streams 25 UK report, however, and does not necessarily Aquifer health 26 reflect the views of each of the contributors. Chalk stream species 26 Since 2012, WWF-UK, Coca-Cola Great Britain and Pressures on chalk streams 31 Coca-Cola Enterprises have been working together Conclusions 42 to secure a thriving future for English rivers. The partnership has focused on improving the health A MANIFESTO FOR CHALK STREAMS 45 of two chalk streams directly linked to Coca-Cola operations: the Nar catchment in Norfolk (where AN INDEX OF ENGLISH CHALK STREAMS 55 some of the sugar beet used in Coca-Cola’s drinks is grown) and the Cray in South London, near 60 to Coca-Cola Enterprises’ Sidcup manufacturing GLOSSARY site. -

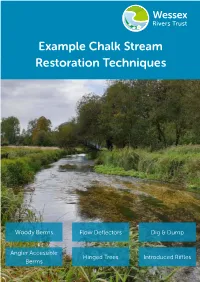

Example Chalk Stream Restoration Techniques Guide

Example Chalk Stream Restoration Techniques Woody Berms Flow Deflectors Dig & Dump Angler Accessible Hinged Trees Introduced Riffles Berms Introduction When it comes to improving habitat on our chalk streams there are several key techniques that we use regularly and form the backbone to many of our projects. Here we introduce some of these techniques to help you envisage exactly what works we propose might look like on your river. As all our key techniques involve working almost entirely with natural materials, there will always be some natural variation in the aesthetics of the finished product. We’ve included plenty of examples, along with a brief description of how we go about the work and what can be achieved with each technique. We’ve also included some examples of our work long after the project has been completed. As you’ll see there can be a significant difference between how works look at installation, and once they are a fully established, naturalistic feature of the river. We hope this information will help us make decisions together about how a finished project could look on your river, ensuring that what we deliver matches your expectations. Healthy rivers for wildlife and people Woody Berms Purpose: Technique: Channel narrowing, meandering and Woody material, placed in the river margins improved marginal refuge/cover habitat. and held tightly in place by stakes and cross braces. Silt that deposits within the structure helps marginal plants to establish and cover over the berm, forming what is essentially new riverbank. Whilst coarse, ‘shaggy’ berms create the best, most natural, habitat, structures can be made neater on sites where presentation is a key constraint. -

Chalk Rivers-EN-Ea001a

l L l L L [ Chalk rivers l nature c~nservation and management I [ l L l [ L [ L ~ L L L L ~ =?\J ENVIRONMENT L G ENGLISH ~~. AGENCY for life [ NATURE L Chalk rivers nature conservation and management March 1999 CP Mainstone Water Research Centre Produced on behalf of English Nature and the Environment Agency (English Nature contract number FIN/8.16/97-8) Chalk rivers - nature conservation and management Contributors: NT Holmes Alconbury Environmental Consultants - plants PD Armitage Institute of Freshwater Ecology - invertebrates AM Wilson, JH Marchant, K Evans British Trust for Ornithology - birds D Solomon - fish D Westlake - algae 2 Contents Background 8 1. Introduction 9 2. Environmental characteristics of chalk rivers 12 2.1 Characteristic hydrology 12 2.2 Structural development and definition of reference conditions for conservation management 12 2.3 Characteristic water properties 17 3. Characteristic wildlife communities ofchalk rivers 20 3.1 Introduction 20 3.2 Higher plants 25 3.3 Algae 35 3.4 Invertebrates 40 3.5 Fish 47 3.6 Birds 53 3.7 Mammals 58 4. Habitat requirements of characteristic wildlife communities 59 4.1 Introduction 59 4.2 Higher plants 59 4.3 Invertebrates 64 4.4 Fish 70 4.5 Birds 73 4.6 Mammals 79 4.7 Summary of the ecological requirements ofchalk river communities 80 5. Human activities and their impacts 83 5.1 The inherent vulnerability of chalk rivers 83 5.2 An inventory of activities and their links to ecological impact 83 5.3 Channel modifications and riverlfloodplain consequences 89 5.4 Low flows 92 5.5 Siltation 95 5.6 Nutrient enrichment 101 5.7 Hindrances to migration 109 5.8 Channel maintenance 109 5.9 Riparian management 115 5.10 Manipulation of fish populations 116 5.11 Bird species of management concern 119 5.12 Decline of the native crayfish 120 5.13 Commercial watercress beds as a habitat 121 5.14 Spread of non-native plant species 121 3 6. -

A National Chalk Stream Restoration Plan

A National Chalk Stream Restoration Plan - the next steps to save our rivers River Nar, Norfolk Charles Rangeley-Wilson Annual Lecture 8 pm Thursday 25 March 2021 by Charles Rangeley-Wilson Prior to the lecture members are also warmly invited to attend the AGM of the Cam Valley Forum at 7.30 pm. Charles Rangely-Wilson’s work and advocacy on behalf of Chalk streams is without equal. Google him. A well-known river environmentalist, author and Wild Trout enthusiast he has been described as 'capturing the essence of time and place in ways that open your eyes to what you are missing'. He is now the Chairman of the National Chalk Stream Restoration Group. This will be used to drive progress by government and the regulators, water companies, land managers, NGOs and river associations - right down to the grass roots level Patrick Rangeley-Wilson of those passionate about their local rivers. The Cam Valley Forum is spearheading action to protect and enhance the Cam Valley's Chalk streams. Our 'River Cam Manifesto', 'Let it Flow! Report, and sustained advocacy have brought progress locally, regionally and nationally. The outputs from the Chalk Stream Restoration Group will give further impetus to our efforts, and those of many other local groups, to guarantee a future for Chalk streams. To register for this event please follow this link: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/cam-valley-forum-agm-annual-talk-national- chalk-stream-restoration-plan-tickets-144011509301. Prior to Charles’ talk, the AGM will start at 7.30 pm (please log on at 7.20 pm to 7.25 pm) and run for 20 minutes or so. -

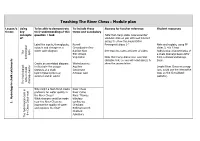

Teaching the River Chess : Module Plan

Teaching The River Chess : Module plan Lesson/s Using To be able to demonstrate To include these Sources for teacher reference Student resources theme key their understanding of this terms and vocabulary concepts question / task Note that many slides have essential of: clickable links so you will need internet access to show the presentation Label the inputs, throughputs, Runoff Powerpoint slides 1-7 Note and explain, using PP outputs and storage on a Groundwater flow slides 3, 4 & 5 how water cycle diagram Surface flow See teachers notes at footer of slides hydrological characteristics of The The cycle Soil storage a chalk drainage basin differ Vegetation Note that many slides have essential from a standard drainage hydrological hydrological clickable links so you will need access to basin. Create an annotated diagram Winterbournes show the presentation to illustrate the unique Aquifers Locate River Chess on a map features of a chalk Catchment (you could use the interactive hydrological cycle in a) Artesian well map on the ChessWatch summer and b) winter website). cycle in chalk in chalk cycle drainage basins drainage The hydrological hydrological The Why might a flash flood create River Chess problems for water quality in River Colne the River Chess? River Thames Hydrology in chalk catchments chalk in Hydrology What changes could be made tributary near the River Chess to confluence 1. improve the quality of water Chesham and regulate the flow? Rickmansworth Chalfont the Chess Catchment Chess the Aylesbury The hydrological cycle in cycle -

Developments in Stream Ecosystem ~ H E O R

Developments in Stream Ecosystem ~heory' G. Wayne Minshall Department of Biology, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID 83209, USA Kenneth W. 6umrnins2 Department sf Fisheries and Widlife, Oregon State University, CorvalEis, OW 9733 1, USA Robert C. Petersen Stream and Benthic Ecology Group, Institute of Limnology, University of bund, 5-22! 1 08 Lund, Sweden Colbert E. Cushing Environmental Sciences Department, Battelle Pacific-Northwest Laboratories, Richland, WA 99352, USA Dale A. Bruns EC & C Idaho, dnc., Environmental Sciences Section, ddaho Falls, ID 834 15, USA Forestry Sciences Laboratory, United States Forest Service, Corvalbis, 88 9733 1, USA and Robin L. Vannote Stroud Water Research Center, Academy of Natural Sciences si Philadelphia, Avondale, PA 198 1 1, USA Minshall, G.We, K. W. Curnrnins, R. C. Petersen, C. E. Cushing, B. A. Bruns, J.R. SedeH, and W. %.Vannote. 1985. Developments in stream ecosystem theory. Can. J.Fish. Aquat. Sci. 42: 1045-1055. Four significant areas ~f thought, (I) the holistic approach, (2) the linkage between streams and their terrestrial setting, (3) material cycling in open systems, and (4) biotic interactions and integration of community ecology principles, have provided a basis for the further development of stream ecosystem theory. The River Continuum Concept (RCC) represents a synthesis of these ideas. Suggestions are made for clarifying, expanding, and refining the RCC to encompass broader spatial and temporal scales. Factors important in this regard include climate and geology, tributaries, location-specific lithology and geo- morphology, and long-term changes imposed by man. It appears that most riverine ecosystems can be accolr~modatedwithin this expanded conceptual framework and that the WCC continues to represent a useful paradigm for understanding and comparing the ecology of streams and rivers. -

Project Write-Up

Project no. GOCE-CT-2003-505540 Project acronym: Euro-limpacs Integrated Project to evaluate the Impacts of Global Change on European Freshwater Ecosystems Instrument type: Integrated Project Priority name: Sustainable Development Deliverable No. 219 Macroinvertebrates as Indicators of Climate-Induced Change in River Ecosystems Due date of deliverable: 27/2/2009 Submission date: 17/03/2009 Start date of project: 01.02.04 Duration: 5 Years Organization name of lead contractor for this deliverable: NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, UK Revision: Draft 1 Integrated Project to evaluate the Impacts of Global Change on European Freshwater Ecosystems WP2: Climate-hydromorphology interactions Task 3: Hydrological changes and aquatic taxa Subtask 3.2: Laboratory experiments Deliverable No. 219 Macroinvertebrates as Indicators of Climate-Induced Change in River Ecosystems Prepared by John Murphy and Ben Warren NERC Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, United Kingdom 2 Aims and Objectives The principle project aim is to assess the suitability of selected freshwater macroinvertebrate species as indicators of climate change in terms of the strength of their response to experimental low-flow treatments. It is hoped that as an outcome, suitable indicator species that occur in groundwater fed rivers will be identified for the climate change scenarios that have been predicted to occur in the UK. The null hypothesis that will be tested is that the experimental manipulation of flows will have no effect on the abundance of any species of invertebrate, or any community level value such as total abundance, or diversity. It is possible to hypothesise that the control channels in this experiment, with normal discharge levels would be expected to have the most diverse macroinvertebrate fauna, with gastropods and crustaceans dominant (Armitage, 1995), whilst the low flow channels will have the least diverse fauna. -

Chalk Rivers & Streams

Chalk Rivers & Streams Why are chalk rivers and streams important? What is a chalk river? A chalk river or stream is a watercourse which flows across chalk bedrock, and/or is influenced by local chalk geology. Chalk rivers are usually fed by underground or seasonal springs flowing from chalk and often have 'winterbourne' stretches in their headwaters which run dry, or partially dry in late summer to the spring. What is the difference between a chalk river and a chalk stream? Chalk rivers and streams are recognised as a priority habitat under the UK Biodiversity Action One of our rarest native mammals the water vole, is often found Plan (BAP), and general descriptions of what living on chalk rivers. Stable water levels and lush, green plant constitutes such habitat are given in ‘The State growth provides ideal conditions for them © P Stevens of England’s Chalk Rivers’ (EA & EN; 2004) and ‘Chalk Rivers – Nature Conservation and England has most of the chalk rivers in Management’ (EA & EN; 1999). Sites are Europe. There are only 35 chalk rivers generally considered to be ‘streams’ rather than between 20 and 90 km long in the UK. They ‘rivers’ when they are no further than 5km from are mostly found in south and east England - their source or greater than 5m wide (unless from Dorset to Humberside. Chalk geology they have been artificially widened). is rare worldwide. The Sussex chalk rivers and streams are therefore of global importance. Chalk rivers All chalk rivers are fed from natural The larger chalk rivers are often more exposed underground aquifers meaning they have to light and therefore have characteristic plants clean, clear water and stable water such as river water crowfoot and watercress in temperatures. -

3. DEVELOPING RIVER WATER BODY ENVIRONMENTAL STANDARDS 3.1 Defining Indices of Hydrological Alteration Stage 1 of the Project R

SNIFFER WFD48 Development of Environmental Standards (Water Resources) Stage 3 3. DEVELOPING RIVER WATER BODY ENVIRONMENTAL STANDARDS 3.1 Defining indices of hydrological alteration Stage 1 of the project reviewed environmental standards and parameters included a literature review to identify the full range of parameters for both rivers and lakes that may need to be controlled and the circumstances in which they are significant. In tandem with this work, a review and appraisal of existing standards, both within the UK and internationally was carried out to determine where there are any gaps – i.e. any parameters that have been identified as relevant but for which there are no existing UK or international standards available. The results of Stage 1 were presented in a report, whose main conclusions were: • Most countries have various methods of determining environmental flows, each defined for a different purpose, e.g. scoping or impact assessment. • Licensing of reservoir releases and abstractions present quite different problems, and different methods have been developed to deal with these issues. With reservoir releases, the flow regime is likely to be subject to significant management (apart from very large floods that by-pass the dam), since it needs to be created. Abstractions, by and large, have no impact on high flows and so the focus is on low flow impacts. • Where data are scarce, expert opinion is used, and increasingly a formal structured approach to getting consensus amongst a group of experts, including academics and practitioners, is favoured. • There is wide acceptance that all parts of the flow regime have some ecological importance.