{PDF EPUB} Mortimer & Whitehouse Gone Fishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gavin Ames Avid Editor

Gavin Ames Avid Editor Profile Gavin is an exceptionally talented editor. Fast, creative, and very technically minded. He is one of the best music editors around, with vast live multi-cam experience ranging from The Isle of Wight Festival, to Take That, Faithless and Primal Scream concerts. Since excelling in the music genre, Gavin went on to develop his skills in comedy, editing Shooting Stars. His talents have since gone from strength to strength and he now has a wide range of high-end credits under his belt, such as live stand up for Bill Bailey, Steven Merchant, Ed Byrne and Angelos Epithemiou. He has also edited sketch comedy, a number of studio shows and comedy docs. Gavin has a real passion for editing comedy and clients love working with him so much that they ask him back time and time again! Comedy / Entertainment / Factual “The World According to Jeff Goldblum” Series 2. Through the prism of Jeff Goldblum's always inquisitive and highly entertaining mind, nothing is as it seem. Each episode is centred around something we all love — like sneakers or ice cream — as Jeff pulls the thread on these deceptively familiar objects and unravels a wonderful world of astonishing connections, fascinating science and history, amazing people, and a whole lot of surprising big ideas and insights. Nutopia for National Geographic and Disney + “Guessable” In this comedy game show, two celebrity teams compete to identify the famous name or object inside a mystery box. Sara Pascoe hosts the show with John Kearns on hand as her assistant. Alan Davies and Darren Harriott are the team captains, in a format that puts a twist on classic family games. -

Rachel Freck - Casting Director

RACHEL FRECK - CASTING DIRECTOR The Office, 28 Elmbourne Rd, London SW17 8JR Tel: 020 8673 2455 Mb No: 07980 585 607 Email: [email protected] Winner of: EMMY AWARD 2009 for Outstanding Casting for a mini-series- for ‘LITTLE DORRIT’ Casting Director: ‘THE OFFICE’, Winner of: GOLDEN GLOBES, BAFTAS, RTS, BRITISH COMEDY AWARDS, TRIC, ETC Winner of Best Casting: BRITISH TELEVISION ADVERTISING CRAFT AWARDS 2004 Films NATIVITY 2 – THE SECOND Feature Film Mirrorball/BBC Films COMING! Director Debbie Isitt By Debbie Isitt Producer Nick Jones TOAST Screenplay By Lee Hall based on the Feature Film Ruby Films/BBC Films Nigel Slater Autobiography Director S. J. Clarkson Producer Faye Ward NATIVITY Feature Film Mirrorball/BBC Films By Debbie Isitt Director Debbie Isitt Producer Nick Jones THE MARK OF CAIN Feature Film Red Productions for Channel 4 Films By Tony Marchant Director Marc Munden Producer Lynn Horsford Exec Producer Nicola Shindler Winner of BAFTA best single drama 2008 CONFETTI Feature Film Improvised Comedy Feature Film for BBC Films by Debbie Isitt Director Debbie Isitt Producers David Thompson for BBC Films & Ian Benson for Wasted Talent THE FESTIVAL Feature Film Film Four and Scottish Screen by Annie Griffin Director Annie Griffin Producers Annie Griffin, Chris Young for Young Pirate Productions Winner of Best Comedy Film – British Comedy Awards 2005 2006 BAFTA nominated for: The Carl Foreman Award for Special Achievement by a British Director The Alexander Korda Award for the Outstanding British Film of the Year THE GREAT PRETENDER Feature Film Starring Ewan McGregor (in development) by Peter Capaldi Director Peter Capaldi Producer Elaine Collins Film for Television HOLY FLYING CIRCUS Film for TV Hillbilly TV for BBC-4. -

Onstage at Bfi Southbank

ONSTAGE AT BFI SOUTHBANK: JANE FONDA, DIRECTOR SEBASTIÁN LELIO (A FANTASTIC WOMAN, DISOBEDIENCE) COMEDY GENIUS GUESTS: LENNY HENRY, JO BRAND, JENNIFER SAUNDERS, TRACY ULLMAN, VIC REEVES AND BOB MORTIMER, DIRECTOR JOHN LANDIS AND COSTUME DESIGNER DEBORAH NADOOLMAN LANDIS, (COMING TO AMERICA), THE CASTS AND CREWS OF NIGHTY NIGHT (INCLUDING JULIA DAVIS, ANGUS DEAYTON, MARC WOOTTON), THE YOUNG ONES (INCLUDING NIGEL PLANER) AND PEOPLE JUST DO NOTHING, COMEDIAN HENNING WHEN AND AUTHOR AND ACTOR DAVID WALLIAMS Film previews: WILDLIFE (Paul Dano, 2018), LIZZIE (Craig William Macneill, 2018), SHOPLIFTERS MANBIKI KAZOKU (Hirokazu Kore-eda, 2018), CREED II (Steven Caple Jr, 2018) TV previews: JANE FONDA IN FIVE ACTS (HBO, 2018), PEOPLE JUST DO NOTHING (BBC/Roughcut Television, 2018), VIC AND BOB’S BIG NIGHT OUT (BBC, 2018), WATERSHIP DOWN (BBC/NETFLIX, 2018) New and Re-Releases: 9 TO 5 (Colin Higgins, 1980), ORPHÉE (Jean Cocteau, 1950), SOME LIKE IT HOT (Billy Wilder, 1959), DISOBEDIENCE (Sebastián Lelio, 2017) Tuesday 18 September 2018, London. The BFI’s 2018 blockbuster season COMEDY GENIUS kicks off at BFI Southbank on Monday 22 October, with a huge number of special events taking place in the first month, including talks from comedy legends Jennifer Saunders, Lenny Henry, Tracey Ullman and Vic and Bob. A highlight of the season will be the BFI re-release of 9 to 5 (Colin Higgins, 1980), back in cinemas as part of the season from Friday 16 November. The film will be previewed at BFI Southbank on Tuesday 23 October, introduced by Jane Fonda. On the same night, Fonda will take part in a very special event Jane Fonda In Conversation, marking the start of a two month season dedicated to her incredible body of work; part one the season will include screenings of Barbarella (Roger Vadim, 1968), Klute (Alan J Pakula, 1971), and Barefoot in the Park (Gene Saks, 1967) the charming rom-com penned by the late Neil Simon. -

Programme 2021 Thank You to Our Partners and Supporters

8–17 October 2021 cheltenhamfestivals.com/ literature #cheltlitfest PROGRAMME 2021 THANK YOU TO OUR PARTNERS AND SUPPORTERS Title Partner Festival Partners The Times and The Sunday Times Australia High Commission Supported by: the Australian Government and the British Council as part of the UK/Australia Season 2021-22 Principal Partners BPE Solicitors Arts Council England Cheltenham BID Baillie Gifford Creative New Zealand Bupa Creative Scotland Bupa Foundation Culture Ireland Costa Coffee Dutch Foundation For Literature Cunard Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands Sky Arts Goethe Institut Thirty Percy Hotel Du Vin Waterstones Marquee TV Woodland Trust Modern Culture The Oldham Foundation Penney Financial Partners Major Partners Peters Rathbones Folio Prize The Daffodil T. S. Eliot Foundation Dean Close School T. S. Eliot Prize Mira Showers University Of Gloucestershire Pegasus Unwin Charitable Trust St. James’s Place Foundation Willans LLP Trusts and Societies The Booker Prize Foundation CLiPPA – The CLPE Poetry Award CLPE (Centre for Literacy in Primary Education) Icelandic Literature Center Institut Francais Japan Foundation Keats-Shelley Memorial Association The Peter Stormonth Darling Charitable Trust Media Partners Cotswold Life SoGlos In-Kind Partners The Cheltenham Trust Queen’s Hotel 2 The warmest of welcomes to The Times and The Sunday Times Cheltenham Literature Festival 2021! We are thrilled and delighted to be back in our vibrant tented Festival Village in the heart of this beautiful spa town. Back at full strength, our packed programme for all ages is a 10-day celebration of the written word in all its glorious variety – from the best new novels to incisive journalism, brilliant memoir, hilarious comedy, provocative spoken word and much more. -

Gone Fishing Bob Mortimer & Paul Whitehouse

GONE FISHING GONE FISHING BOB MORTIMER & PAUL WHITEHOUSE Published by Blink Publishing The Plaza, 535 Kings Road, Chelsea Harbour, London, SW10 0SZ www.blinkpublishing.co.uk facebook.com/blinkpublishing twitter.com/blinkpublishing Hardback – 978-1-7887-019-5-2 Ebook – 978-1-7887-020-3-4 All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or circulated in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing of the publisher. A CIP catalogue of this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by seagulls.net Copyright © Owl Power, 2019 Bob Mortimer and Paul Whitehouse have asserted their moral right to be identified as the authors of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All images © Bob Mortimer and Paul Whitehouse, except p. 6, 22, 78, 92, 111, 198, 234, 244 © John Bailey; p. 60, 102, 217 © Getty Images; and p. 206 Bridgeman Image Archive. BBC and the BBC logo are trademarks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 1996. Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them. This work contains general information on heart health. The information is not medical advice and should not be treated as such. The information is provided without any representations or warranties, express or implied. -

Frankie Boyle

Frankie Boyle “His stand-up act is honed to gilt-edged perfection” The List Frankie Boyle is a stand-up comedian and writer. Frankie first established himself as a household name on BBC2’s topical news quiz Mock The Week, fast garnering a devoted audience for his unique brand of razor-sharp satirical comedy. Since leaving the show to pursue other projects, he has continued to be one of the most popular and sought-after comics working in the UK, creating his own Channel 4 shows Tramadol Nights and The Boyle Variety Performance, while also performing sold-out tours across the UK. Most recently Frankie created three political specials for the BBC, Referendum Autopsy, Election Autopsy and American Autopsy, each released to widespread critical and public acclaim. Other recent TV credits include Live at the Apollo, Room 101, QI, Kevin Bridges: Live at the Referendum and an original comedy short for BBC iPlayer entitled Frankie Boyle and Bob Mortimer’s Cooking Show. Frankie has also been a guest on and hosted Have I Got News For You and has made appearances on shows such as Would I Lie To You?, The Jonathan Ross Show and 8 Out Of 10 Cats. His live work has seen him complete three nationwide sell-out tours, his 2012 show Last Days Of Sodom, culminating in a string of arena dates. His latest show, Hurt Like You’ve Never Been Loved, toured across the UK and is now available on Netflix, making him only the second UK comedian ever to create exclusive stand-up content for the online streaming behemoth. -

Paul Whitehouse and Bob Mortimer

22 DAILY STAR, Monday, June 18, 2018 DAILY STAR, Monday, June 18, 2018 23 Ultimate MATES REVEAL REEL REASON BEHIND FISHING SHOW BBQ kits BOB’S WINTHE rare glimpse of British summer competition. Call 0905 789 3506 has fi nally arrived & what is summer (80ppm)* or text DSPRIZE9 followed for if not to enjoy a 5 star BBQ. by your email address, name and PAUNCH At Gourmet Burger Kitchen, we address to 84902 (£2)**. LINE: Comic want to support you in your summer Or to enter via post send your mates Paul and FAVES grilling mission. name, address, phone number, Bob go fi shing and SONG: Why (Annie Lennox) We want to make sure you cannot email address, age and gender in a become hooked on TV SHOW: The American Offi ce only enjoy our burgers in our sealed envelope to GBK BBQ Kit a new healthy(ish) FILM: A Room For Romeo Brass restaurants nationwide, but you can Competition, PO BOx 12581, diet after their ACTOR: Jeff Bridges also now recreate the gourmet Sutton Coldfi eld B73 9BX. One heart scares. Left, COMEDIAN: Matt Berry burger experience at home. entry per letter. with our Mike SPORTS STAR: Adama Traoré, That’s why we are giving 3 people This competition closes at Middlesbrough the chance to enjoy 1 of 3 Ultimate midnight on 12.08.18 and three FOOD: Potato BBQ Kits which includes 1 Premium working days later for postal entries. BBQ worth a value of £169.99, a set DRINK: Pale Ale HOLIDAY DESTINATION: Palm of BBQ tools, £50 worth of GBK *Calls cost 80p per minute plus your from all valid entries. -

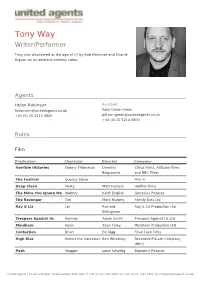

Tony Way Writer/Performer

Tony Way Writer/Performer Tony was discovered at the age of 17 by Bob Mortimer and Charlie Higson on an amateur comedy video. Agents Helen Robinson Assistant [email protected] Polly Dixon-Green +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company Horrible Histories Enemy Tribesman Dominic Citrus Films, Altitude Films Brigstocke and BBC Films The Festival Queasy Steve Film 4 Deep Clean Malky Matt Harlock Halflife Films The More You Ignore Me Wobbly Keith English Genesius Pictures The Revenger Tim Mark Murphy Family Dies Ltd Ray & Liz Lol Richard Ray & Liz Production Ltd Billingham Trespass Against Us Norman Adam Smith Trespass Against Us Ltd Mindhorn Kevin Sean Foley Mindhorn Production Ltd Confection Brian Ed Rigg Final Take Films High Rise Robert the Caretaker Ben Wheatley Recorded Picture Company (RPC) Posh Mugger Lone Scherfig Blueprint Pictures United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company Alice Through the Witzender 1 James Bobin Disney Looking Glass Edge of Tomorrow Kimmel Doug Liman Warner Bros. Brand New-U Gun Dealer/Santa Simon Pummell Finite Films Convenience Stoner 2 Convenience Films Sightseers Crich Tourist Ben Wheatley Big Talk Productions Convenience Keri Collins Urban Way Productions The Girl with the Plague David Fincher Sony Pictures Dragon Tattoo Anonymous Thomas Nashe Roland Emmerich Vierzehnte Babelsberg Film GmbH London Boulevard Lone Paparazzo William Monahan GK Films Down Terrece Garvey Ben Wheatley Mr and Mrs Wheatley Trimming the Fat Short Matt Huntley Idiotlamp/BBC Films Legend of the Golden Gavin Fishcake Beyond the Pole Landlord David L. -

Vanessa White Hair and Make-Up Designer

Vanessa White Hair and Make-up Designer Vanessa White is a multi-award winning Hair & Makeup Designer, who has worked across a vast amount of television and feature films. Vanessa has considerable experience with Prosthetics and Makeup transformations. Agents Madeleine Pudney Assistant 020 3214 0999 Eliza McWilliams [email protected] 020 3214 0999 Credits Film Production Company Notes THIS NAN'S LIFE Warner Bros. Dir: Josie Rourke 2019 Prod: Damian Jones ALL IS TRUE TKBC / Sony Pictures Dir: Kenneth Branagh 2018 Classics Prods: Kenneth Branagh, Ted Gagliano, Judy Hofflund, Becca Kovacik and Tamar Thomas ALAN PARTRIDGE Baby Cow Films / Dir: Declan Lowney 2013 StudioCanal Prods: Kevin Loader & Henry Normal THE HARRY HILL Entertainment Film Dir: Steve Bendelack MOVIE Distributors Prod: Robert Jones 2013 GRAVITY Warner Bros. Special Effects Hair & Makeup Designer 2013 Dir: Alfonso Cuarón Prods: Alfonso Cuarón & David Heyman United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes BRIDGET JONES'S Miramax Additional Photography DIARY Dir: Sharon Maguire 2001 Prod: Tim Bevan, Jonathan Cavendish & Eric Fellner Television Production Company Notes THIS SCEPTRED ISLE Revolution Films / Dirs: Julian Jarrold & Michael 2021 Freemantle / Sky Winterbottom Prods: Josh Hyams, Melissa Parmenter & Anthony Wilcox MOTHERLAND SERIES 3 Merman / BBC 2020 HARRY HILL'S ALIEN FUN ITV / Nit Productions Dirs: Geraldine Dowd and Tom CAPSULE Vinnicombe 2019 -

Bob Mortimer

CLAIM NO. HC-2017-000981 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE BUSINESS AND PROPERTY COURTS BUSINESS LIST BUSINESS B E T W E E N:- BOB MORTIMER Claimant and NEWS GROUP NEWSPAPERS LIMITED Defendant STATEMENT IN OPEN COURT Solicitor for the Claimant 1. In this action for misuse of private information, I appear for the Claimant. My learned friend, Anthony Hudson QC appears for the Defendant. 2. The Claimant is a former solicitor, now a comedian, presenter, writer and actor. He is well-known for his double act in Vic & Bob with Vic Reeves (real name James Moir), and appeared regularly on prime-time television in shows including Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased), Catterick, Never Mind the Buzzcocks and Vic & Bob’s Afternoon Delights, as well as the game show Shooting Stars, with Mark Lamarr, Matt Lucas and Ulrika Jonsson. The Claimant was subject to media coverage as a result of his celebrity status and close relationships with other high-profile people. 3. The Defendant is NGN Limited, a subsidiary company of News Corp UK and Ireland Limited trading as News UK. NGN Limited was the publisher of the News of the World newspaper until its closure in July 2011. It also publishes The Sun. Both the News of the World and The Sun were high circulation newspapers which were read by millions during the relevant period. 9378227.DOCX version 1 4. The Claimant instructed solicitors to investigate matters after his close friend, Jim Moir, was contacted by the MPS to confirm that they had found the name and contact details of Mr. -

BBC Puts Accent on North a Keynote Lecture by Peter Salmon Director

Can You Hear It? BBC puts Accent on North A keynote lecture by Peter Salmon Director, BBC North Good evening. It is good to be in Sunderland — home to the fastest counters in the country, as we all saw on Election night. All the drama that opening the ballot boxes has resulted in started right here. Amazing to think that 40 million people watched some of that remarkable Election Campaign on the BBC. I don’t think I can beat that drama tonight — nor can I match the excitement of the new Dr Who’s appearance here a few weeks ago for an exclusive screening of the first episode of the new series for local children - but I do hope I can give you a sense of some of the change already underway in the BBC that I hope will have a growing impact on your lives over the next few years. I’d like to thank Graeme and the RTS in the North East for inviting me and providing this chance to talk to you about our big move North next year and the opportunities it can create for programme making here in the Northeast. I’d ask your forgiveness in advance if I talk about The North as though it were a single place as opposed to a whole series of great cities and towns and regions of England. As I hope to explain today though, I do think there is much that binds us together — not as little northerners, reduced to settling for second best, but citizens of the greater north, unified in ambition and confidence. -

Shedding Light on Dark Comedy

Shedding Light on Dark Comedy: Humour and Aesthetics in British Dark Comedy Television Rebecca Louisa Collings Submitted for the qualification of PhD University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies September 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution”. Abstract The term ‘dark comedy’ is used by audiences, producers and academics with reference to an array of disparate texts, yet attempts to actually define it perpetuate a sense of confusion and contradiction. This suggests that although there is a kind of comedy that is common enough to be widely noted, and different enough from other types to require separation, how and why this difference can be perceived could be better understood. Accordingly, I investigate what is enabling the recognition and distinction in respect of British dark comedy programmes, and use this as a basis for considering how this type of comedy works. I argue that the programmes may be distinguished primarily by aesthetic features, placing their rise on British television in a broader context of aesthetic trends towards a display of visual detail, spectacle, and excess that puts the private and the taboo on greater show. Using the theories of Freud, Bakhtin, and Bergson about taboo, the uncanny, the grotesque, and the appearance of mechanical actions in humans, I examine in detail examples of British comedy television programmes that are typically referred to as ‘dark’, demonstrating their consistent depiction of subjects that are often repressed or avoided, particularly those around which taboo restrictions and prohibitions have evolved (such as violence and death, illness, and transgressive sexuality).