Download (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competition in Financial Services: the Impact of Nonbank Entry

UJ OR-K! Federal iesarve Bank F e d .F o o . | CA, Philadelphia HB LIBRARY .SlXO J 9 ^ 3 - / L ___ 1__ ,r~ Competition in Financial Services: The Impact of Nonbank Entry Harvey Rosenblum and Diane Siegel FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF CHICAGO Staff Study 83-1 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Competition in Financial Services: The Impact of Nonbank Entry Harvey Rosenblum and Diane Siegel Staff Study 83-1 '■n Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis TABLE OF CONTENTS page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i INTRODUCTION 1 BACKGROUND 3 Citicorp Study-1974 3 Recent Studies 7 CO M PETITIO N IN FINANCIAL SERVICES: 1981-82 10 Overview 11 Consumer Credit 16 Credit Cards 23 Business Loans 26 Deposits 30 POLICY IMPLICATIONS 35 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 39 FOOTNOTES 40 REFERENCES 42 APPENDIX A Accounting Data for Selected Companies A1-1 Insurance Activities of Noninsurance-Based Companies A2-1 APPENDIX B: COMPANY SUMMARIES Industrial-, Communication-, and Transportation-Based Companies B1-1 Diversified Financial Companies B2-1 Insurance-Based Companies B3-1 Oil and Retail-Based Companies B4-1 Bank Holding Companies B5-1 Potential Entrants B6-1 APPENDIX C: THREE CHRONOLOGIES ON INTERINDUSTRY AND INTERSTATE DEVELOPMENTS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CASH MANAGEMENT PRODUCTS: 1980-82 Introduction and Overview C1-1 Interindustry Activities C1-2 Interstate Activities C2-1 Money Market and Cash Management-Type Accounts C3-1 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve -

The Reinsurance Company No One Wants Capital, GE Plans to Inject $1.8 Billion Into at ERC in 1999, the Company Sported Top GE’S Employers Re the Company

SM SCHIFFThe world’s most dangerous’ insuranceS publication November 22, 2002 Volume 14 • Number 17 INSURANCE OBSERVER The Reinsurance Company No One Wants capital, GE plans to inject $1.8 billion into at ERC in 1999, the company sported top GE’s Employers Re the company. (In the past five years ERC ratings from Best, S&P, and Moody’s. n early 1999 we placed a call to has upstreamed $2 billion in dividends to Those ratings are now history. As recently General Electric Capital—the parent its parent company.) GE also announced as July 10, Best affirmed ERC’s “A++” rat- of Employers Re (ERC), one of the a $4.5 billion infusion into GE Capital, ing, commenting on the company’s “ex- Iworld’s largest reinsurance organiza- whose balance sheet is stretched a bit cellent stand-alone capitalization; leading tions. We wanted to discuss a series of thin. (GE Capital has $260 billion of debt global market position, and prospective ERC ads that carried the famous GE logo outstanding.) long-term earnings capability.” On and that stated, in a variety of ways, that Until 2000, ERC had been reporting October 14, in light of the company’s ERC’s policies were “backed by” GE’s profits that did not upset Jack Welch’s gut. problems, Best revised its rating to “A+”, “resources” and “capital reserves.” Now it’s clear that ERC’s recent earn- expressing its “concerns regarding GE’s ERC’s ads were misleading and de- ings were an illusion resulting long-term commitment to GE Global ceptive because they gave the false im- from—we say this with all due re- [ERC’s direct parent] due to its pression that GE—as opposed to ERC— spect—honest mistakes made by bias against earnings volatility in- had financial responsibility for ERC’s GE stock-option holders trying to herent in GE Global’s non-life obligations. -

SEC News Digest, 07-09-1985

""~B~C new~.~~~lS~'~5t EXCHANGE COMMISt)ION CIVIL PROCEEDINGS SETTLEMENT REACHED BETWEEN SEC AND NEAL R. GROSS AND CO., INC. George G. Kundah1, Executive Director of the Commission, announced that on June 21 a settlement was reached between the Commission and Neal R. Gross and Co., Inc., the Commission's former stenographic reporting contractor. On June 13, 1982, the Commis- sion issued a default against Gross for late and poor quality transcripts. Gross sub- sequently appealed the default to the Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals, and claimed entitlement to excess performance costs in the amount of $706,691.66. Under the terms of the Settlement Agreement, Gross agrees to withdraw its claim for $706,691,661 the default is rescinded and the contract cancelled as of June 13, 19831 Gross agrees not to bid on any Commission contracts for reporting services for 15 years 1 and the Commission agrees to return $25,681 which it had drawn against Gross' performance bond, and $1,062.01 in incorrectly calculated discounts, plus interest on these amounts. (Appeals of Neal R. Gross and Co., Inc., ASBCA NOS. 28776 and 29982, filed October 26, 1983 and September 7, 1984, respectively). (LR-10810) CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS . CHARLES J. ASCENZI INDICTED The washington Regional Office announced that on June 18 a grand jury in West Palm Beach, Florida named Charles J. Ascenzi of Silverdale, pennsylvania in a two-count indictment alleging wire fraud and the filing of false documents with a bank having deposits insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. The indictment alleges that Ascenzi fraudulently obtained $625,000 from the proceeds of an industrial revenue bond issue by the City of West Memphis, Arkansas for the benefit of Maphis Chapman Corporation of Arkansas. -

Coca-Cola Building 2104 Grand Avenue Completed 1915

Missouri Valley Special Collections Coca-Cola Building 2104 Grand Avenue completed 1915 by Ann McFerrin Most people in the Kansas City area know the tall and distinctive landmark building at 21st and Grand as the Western Auto Building. Earlier Kansas City residents knew it under two other names: the Candler Building, and its original moniker, the Coca-Cola Building. By the early twentieth century, the future of Kansas City showed great promise. The population in the 1880s was 60,000; by 1909 it had grown to 248,000. With its central location, the city became a focus for commerce and industry, including livestock and agricultural-related businesses, banking, and the railroad industry, among others. Several national companies placed regional headquarters here, such as Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck and Company. Finally, there were plans in the works for the building of a new train station near 24th and Main streets. It was this thriving city that attracted Asa G. and Charles H. Candler, president and vice-president respectively of the Coca- Cola Company of Atlanta. Asa Candler commented about their search for a place in the central west of America in which the company could build a new plant and distribution center: We learned that twenty states of the union, embracing more than two million square miles with a population exceeding twenty-five million people, were more advantageously served by Kansas City than by any other city, and that the distributing facilities of Kansas City were superior to any other in this district . We found it to be equally advantageously located for passenger traffic . -

Lehman Brothers

Lehman Brothers Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. (Pink Sheets: LEHMQ, former NYSE ticker symbol LEH) (pronounced / ˈliːm ə n/ ) was a global financial services firm which, until declaring bankruptcy in 2008, participated in business in investment banking, equity and fixed-income sales, research and trading, investment management, private equity, and private banking. It was a primary dealer in the U.S. Treasury securities market. Its primary subsidiaries included Lehman Brothers Inc., Neuberger Berman Inc., Aurora Loan Services, Inc., SIB Mortgage Corporation, Lehman Brothers Bank, FSB, Eagle Energy Partners, and the Crossroads Group. The firm's worldwide headquarters were in New York City, with regional headquarters in London and Tokyo, as well as offices located throughout the world. On September 15, 2008, the firm filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection following the massive exodus of most of its clients, drastic losses in its stock, and devaluation of its assets by credit rating agencies. The filing marked the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history.[2] The following day, the British bank Barclays announced its agreement to purchase, subject to regulatory approval, Lehman's North American investment-banking and trading divisions along with its New York headquarters building.[3][4] On September 20, 2008, a revised version of that agreement was approved by U.S. Bankruptcy Judge James M. Peck.[5] During the week of September 22, 2008, Nomura Holdings announced that it would acquire Lehman Brothers' franchise in the Asia Pacific region, including Japan, Hong Kong and Australia.[6] as well as, Lehman Brothers' investment banking and equities businesses in Europe and the Middle East. -

Pueblo Subject Headings

Pueblo Subject Headings Thursday, March 28, 2019 1:22:33 PM Title See See Also See Also 2 File Number 29th Street Barber Styling see Business - 29th Street Barber Styling 29th Street Sub Shop see Business - 29th Street Sub Shop 3-R Ranch see Ranches - 3-R Ranch 4-H see Clubs - Pueblo County 4-H 4-H - Pueblo County see Clubs - Pueblo County 4-H 5th and Main Expresso Bar see Business - 5th and Main Expresso Bar 6th Street Printing see Business - 6th Street Printing 7-11 Stores see Business - 7-11 Stores 8th Street Baptist Church see Churches - 8th Street Baptist A & W Restaurant see Business - A & W Restaurant A Balloon Extravaganza see Business - Balloon Extravaganza, A A Better Realty see Business - A Better Realty A Community Organization for see ACOVA (A Community Victim Assistance (ACOVA) Organization for Victim Assistance) Page 1 of 423 Title See See Also See Also 2 File Number A. B. Distributing Company see Business - A. B. Distributing see also Business - American Company Beverage Company A. E. Nathan Clothing see Business - A. E. Nathan Clothing A. P. Green Refractories Plant see Business - A. P. Green Refractories Plant A-1 Auto Sales see Business - A-1 Auto Sales A-1 Rental see Business - A-1 Rental AAA Plumbing see Business - AAA Plumbing ABBA Eye Care see Business - ABBA Eye Care ABC Manufactured Housing see Business - ABC Manufactured Housing ABC Plumbing see Business - ABC Plumbing ABC Rail see Business - ABC Rail ABC Support Group see Business - ABC Support Group Abel Engineers see Business - Abel Engineers Aberdeen see -

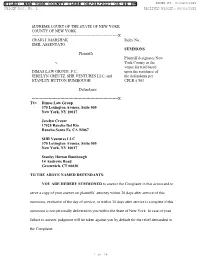

Filed: New York County Clerk 06/04/2021 06:46 Pm Index No

FILED: NEW YORK COUNTY CLERK 06/04/2021 06:46 PM INDEX NO. 653623/2021 NYSCEF DOC. NO. 1 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 06/04/2021 SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------------------X CRAIG J. MARSHAK, Index No.: EMIL ASSENTATO SUMMONS Plaintiffs Plaintiff designates New v. York County as the venue for trial based DIMAS LAW GROUP, P.C., upon the residence of JERELYN CREUTZ, SHR VENTURES LLC, and the defendants per STANLEY HUTTON RUMBOUGH CPLR § 503 Defendants ------------------------------------------------------------------X TO: Dimas Law Group 370 Lexington Avenue, Suite 505 New York, NY 10017 Jerelyn Creutz 17525 Rancho Del Rio Rancho Santa Fe, CA 92067 SHR Ventures LLC 370 Lexington Avenue, Suite 505 New York, NY 10017 Stanley Hutton Rumbough 14 Andrews Road Greenwich, CT 06830 TO THE ABOVE NAMED DEFENDANTS: YOU ARE HEREBY SUMMONED to answer the Complaint in this action and to serve a copy of your answer on plaintiffs’ attorney within 20 days after service of this summons, exclusive of the day of service, or within 30 days after service is complete if this summons is not personally delivered to you within the State of New York. In case of your failure to answer, judgment will be taken against you by default for the relief demanded in the Complaint. 1 of 18 FILED: NEW YORK COUNTY CLERK 06/04/2021 06:46 PM INDEX NO. 653623/2021 NYSCEF DOC. NO. 1 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 06/04/2021 Dated: New York, New York June 4, 2021 GUZOV, LLC By: _____________________ Debra J. Guzov, Esq. David J. Kaplan, Esq. -

Behavior Modification

Providing Global Opportunities for the Risk-Aware Investor Behavior Modification Author Michael Lewis must feel like Yogi Berra with déjà vu all over again. In 1989, as the country was looking in the rear view mirror at a major market crash preceded by a decade of overindulgence, he published “Liar’s Poker.” His personal account of working at Salomon Brothers in the 1980’s told the tale of testosterone-charged bond traders and their relentless pursuit of money and power. The book became an instant classic on Wall Street, and somewhat of a playbook for aspiring Gordon Gekkos. He labeled that era to be a “rare and amazing glitch” in the history of earning a living. Today, as we read the emails and listen to the stories of deals constructed during the earlier years of the 2000’s, it seems that the “rare” money-making opportunity of the 1980’s was not so rare after all. As our legislators craft the details of financial reform, we think it is important that they focus not just on how to extricate ourselves from the next crisis, but on how to best prevent one. The main goal of this paper is to illuminate the central points of financial reform legislation now being debated in Congress. In order to do that, we must first address the important question: “What led us to this point?” Twenty years after “Liar’s Poker” Michael Lewis has published another book, “The Big Short,” in which he chronicles the accounts of a handful of investors who bet on and profited from the collapse of the subprime mortgage market. -

(NAARS): Official Listing of the Corporations Comprising the 1972 Annual Report File

University of Mississippi eGrove American Institute of Certified Public Guides, Handbooks and Manuals Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection 1972 National Automated Accounting Research System (NAARS): Official Listing of the Corporations Comprising the 1972 Annual Report File American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_guides Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), "National Automated Accounting Research System (NAARS): Official Listing of the Corporations Comprising the 1972 Annual Report File" (1972). Guides, Handbooks and Manuals. 703. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aicpa_guides/703 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) Historical Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides, Handbooks and Manuals by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NATIONAL AUTOMATED ACCOUNTING RESEARCH SYSTEM NAARS OFFICIAL LISTING OF THE CORPORATIONS COMPRISING THE 1972 ANNUAL REPORT FILE PAGE 1 1972 ANNUAL REPORT FILE ALPHABETICAL LISTING COMPANY NAME SIC S EX B S DATE AUDITOR A & E PLASTIK PAK CO., INC. 309 ASE 12-31-72 PMM A.B. DICK COMPANY 508 OTC 12-31-72 AA A.E. STALEY MANUFACTURING COMPANY 204 NySE 09-30-72 HS a.g. Edwards & sons inc 621 ASE 02-28-73 TR a.h. rOBins company, incorporated 283 NYSE 12-31-72 a.m. pullen & company a.M. castle & co. 509 ASE 12-31-72 AA a.o. smith corporation 371 NYSE 12-31-72 ay a.p.s. -

TENANT CREDIT RATINGS 3Rd Quarter 2019

TENANT CREDIT RATINGS 3rd Quarter 2019 Provided to you by: The O’Shea Net Lease Advisory The O’Shea Net Lease Advisory TENANT CREDIT RATINGS MOODY’S AND STANDARD & POOR’S Table of Contents Tenant Credit categories 1 Auto-related 2 Telecommunications 3 Financial Services 4 Home Improvement/Home Furniture 5 Big Box Retailers 6 Retailers: Department Stores/Clothing 7 Specialty Retailers, Health/ Hotels 8 Drug Stores 9 Grocery Store 10 QSR's 11 Medical 12 The O’Shea Net Lease Advisory TENANT CREDIT RATINGS MOODY’S AND STANDARD & POOR’S RETAIL TENANT LIST WITH TICKER SYMBOLS & CREDIT RATING -3rd Quarter 2019- CREDIT TENANCY MOODY’S STANARD & POOR’S Highest Quality Aaa AAA High Quality Aa AA Upper Medium Grade A A Medium Grade Baa BBB Lower Medium Grade* Ba BB Lower Grade* B B Poor Quality” Caa CCC Speculative* Ca CC No Interest Being Paid or BK Petition Filed” C C Note: The ratings for Aa to Ca by Moody’s may be modified by the addition of a 1, 2, or 3 to show the relative standing within the category. 1=High 3=Low * Below investment Grade 01 The O’Shea Net Lease Advisory TENANT CREDIT RATINGS MOODY’S AND STANDARD & POOR’S TENANT TICKER MOODY’S S&P SUBSIDIARIES, AFFILIATES, AND BRAND NAMES AUTOMOTIVE Advanced Auto Parts, Inc. AAP Baa2 Stable BBB- Stable Advanced Auto Parts, Western Auto Supply, Discount Auto Parts, Autopart International, Motologic, General Parts International, Worldpac, Carquest Ashland, Inc. ASH Ba1 Stable BB Negative Ashland Oil, Valvoline AutoNation, Inc. AN Baa3 Stable BBB- Stable AutoNation AutoZone, Inc. -

Norby Collection Databases, Brookings Businesses Listed by Avenue Address SDSU Archives and Special Collections, Hilton M

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Regional Collections Finding Aids 5-15-2018 Norby Collection Databases, Brookings Businesses Listed by Avenue Address SDSU Archives and Special Collections, Hilton M. Briggs Library Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/finding_aids-regional Recommended Citation SDSU Archives and Special Collections, Hilton M. Briggs Library, "Norby Collection Databases, Brookings Businesses Listed by Avenue Address" (2018). Regional Collections. 5. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/finding_aids-regional/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Regional Collections by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brookings Businesses 1879-2003 Arranged by Avenue This material was compiled by George Norby. It is arranged as follows: avenue name, street address, year, business. Information may include: business name, owner, employees, location moved to, closing dates, other relevant information that may be of interest to researchers The following information is as accurate as possible and was gathered from the following sources: • Brookings County Press, October 22, 1879—April 1948 • Brookings Register, June 3, 1890- 2003 • Brookings County Sentinel, various issues, 1882—1889 • Brookings Telephone Directories and Business directories, various issues, 1901—2003 • 1908 business listing published in the Brookings Register June 29, 1979 • Brookings City Publications • Brookings County election returns • Brookings County Commission Minutes • Records in the Brookings Count Register of Deeds office It is recommended that researchers verify information from more than one source in order to conduct an accurate search. -

The Best Part Is Our People

The best part is our people. 2001 Annual Report Advance Auto Parts Contents Financial Highlights 2 Stockholders’ Letter 4 Company History 6 Our Stores 9 Supply Chain 12 Commercial Program 15 Financials And Other Information 16 Maine 7 Vermont 2 New Hampshire 4 Wisconsin Massachusetts 20 South Dakota 6 16 New York 96 Wyoming 2 Michigan Rhode Island 3 47 Connecticut 24 Iowa 24 Pennsylvania 132 Nebraska 16 New Jersey 21 Ohio 140 Illinois 23 Indiana Delaware 5 Colorado 15 68 West Maryland 30 Virginia Virginia 125 Kansas 26 62 Missouri 37 Kentucky 66 North Carolina 174 Tennessee 117 Oklahoma 2 Arkansas 21 South Carolina 100 Mississippi Georgia 253 65 Alabama 113 Louisiana Texas 51 70 Florida 461 California 1 Puerto Rico 37 Virgin Islands 2 Advance Auto Parts, Inc. is the second-largest auto stores. As a result What makes an Advance Auto Parts parts retailer in the United States. We ended our 2001 of our expansion store unique? Why are more and more do- fiscal year on December 29, 2001 with 2,484 stores from both new it-yourselfers and professional installers in 38 states, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. store openings and choosing us despite the many alternatives We experienced substantial growth during strategic acquisitions, we are the largest available? Once you have visited one of 2001. The most dramatic indication was the specialty retailer of automotive products our stores, you’ll know. It’s the broad increase in the number of stores we in a majority of the states where we do selection of products.