Eng Ground Floor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

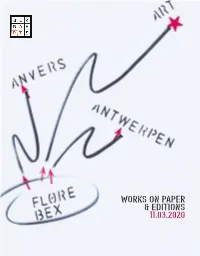

Works on Paper & Editions 11.03.2020

WORKS ON PAPER & EDITIONS 11.03.2020 Loten met '*' zijn afgebeeld. Afmetingen: in mm, excl. kader. Schattingen niet vermeld indien lager dan € 100. 1. Datum van de veiling De openbare verkoping van de hierna geïnventariseerde goederen en kunstvoorwerpen zal plaatshebben op woensdag 11 maart om 10u en 14u in het Veilinghuis Bernaerts, Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen 2. Data van bezichtiging De liefhebbers kunnen de goederen en kunstvoorwerpen bezichtigen Verlatstraat 18 te 2000 Antwerpen op donderdag 5 maart vrijdag 6 maart zaterdag 7 maart en zondag 8 maart van 10 tot 18u Opgelet! Door een concert op zondagochtend 8 maart zal zaal Platform (1e verd.) niet toegankelijk zijn van 10-12u. 3. Data van afhaling Onmiddellijk na de veiling of op donderdag 12 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u op vrijdag 13 maart van 9 tot 12u en van 13u30 tot 17u en ten laatste op zaterdag 14 maart van 10 tot 12u via Verlatstraat 18 4. Kosten 23 % 28 % via WebCast (registratie tot ten laatste dinsdag 10 maart, 18u) 30 % via After Sale €2/ lot administratieve kost 5. Telefonische biedingen Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 Veilinghuis Bernaerts/ Bernaerts Auctioneers Verlatstraat 18 2000 Antwerpen/ Antwerp T +32 (0)3 248 19 21 F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 www.bernaerts.be [email protected] Biedingen/ Biddings F +32 (0)3 248 15 93 Geen telefonische biedingen onder € 500 No telephone biddings when estimation is less than € 500 Live Webcast Registratie tot dinsdag 10 maart, 18u Identification till Tuesday 10 March, 6 pm Through Invaluable or Auction Mobility -

PRCUA Naród Polski

The Official Publication of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America for 115 Years! No. 1 - Vol. CXXV January 1, 2011 - 1 stycznia 2011 HAPPY NEW YEAR Celebrating 125 Years of PRCUA 2011 Publications and Narod Polski’s 115th Anniversary! This year marks the 125th anniversary of PRCUA’s official publications in the Polish American communities in many different states. This meeting general and the 115th anniversary of “Narod Polski.” Throughout the history of brought about the establishment of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of our fraternal, the organization’s publication has played a crucial role in America (PRCUA), a fraternal organization with the motto “For God and disseminating information about the PRCUA, its goals and ideals. It has been Country.” the vehicle used by the PRCUA to rally its members together in a fraternal The first goals of the organization were: 1)to build Polish churches and brotherhood of noble ideals centered around our Polish heritage and values. schools; 2) to promote adherence to the Roman Catholic religion, and the In June, 1873, Rev. Theodor Gieryk, pastor of St. Albertus Parish in Detroit, religious and cultural traditions of the Polish nation; 3) to give fraternal Michigan, wrote letters to the editors of Polish language newspapers assistance to Poles; 4) to take care of widows and orphans; 5) to help Poland to throughout America. He urged Poles in America to unite by forming a national become an independent country again, and 6) to establish “Pielgrzym” as the organization to protect Polish immigrants from discrimination and to preserve organization’s official organ. -

Etude Interreg

Rapport d’expertise sur l’évolution du territoire Bas-Normand au 20e siècle via l’analyse de son patrimoine maritime, militaire et industriel. TABLE DES MATIERES 1. Introduction p. 3 2. Méthodologie p. 5 2.1 Législation et zones protégées p. 5 2.2 L’étude p. 5 2.3 Consultations p. 7 3. Environnement – Patrimoine archéologique et culturel p. 8 3.1 Évaluation du caractère paysager p. 8 3.1.1 Introduction au territoire bas-normand et paysage portuaire p. 8 3.1.2 Définition de la zone d’étude p. 9 3.1.3 Géologie p. 9 3.1.4 Topographie p. 9 3.1.5 Hydrologie : caractère estuarien / fluvial ; port naturel p. 11 3.1.6 Patrimoine historique du territoire p. 12 3.1.7 Habitat suburbain p. 13 3.1.8 Activité économique du territoire p. 13 3.2 L’Inventaire général p. 15 3.3 Inventaire raisonné des entités du territoire étudié p. 18 3.4 Répartition spatiale des entités MMI p. 23 3.5 Etude chronologique du territoire p. 27 3.6 Données démographiques et facteurs socio-économiques p. 44 3.6.1 Données démographiques p. 44 3.6.2 L’emploi sur le territoire p. 47 3.6.3 Zoom sur l’emploi dans le domaine touristique p. 50 3.7 L’activité touristique p. 55 3.7.1 Etat des lieux de la fréquentation touristique sur le territoire p. 55 3.7.2 Le poids économique de la fréquentation touristique p. 60 3.7.3 Analyse du potentiel de valorisation des sites MMI du territoire métropolitain p. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Titanic, Retour À Cherbourg

DOSSIER DE PRESSE 2019 TITANIC, RETOUR À CHERBOURG CONTACTS PRESSE CHARGÉE DES RELATIONS PRESSE - LUCIE LE CHAPELAIN - [email protected] - 06 80 32 54 30 CHARGÉE DE LA COMMUNICATION DIGITALE - GISÈLE GUIFFARD - [email protected] - 02 33 20 26 67 La tragédie du Titanic est Maritime Transatlantique des années trente, aux présente dans les esprits lignes Art déco, dernier témoin en Europe de et alimente encore les ce que fut le plus grand exode de l’humanité. imaginations. Que vous Partez à la rencontre de ces dizaines de millions ayez 7 ou 77 ans, vous d’hommes et de femmes, qui ont tout quitté, êtes happé par cette animés du seul rêve d’une vie meilleure. histoire. Vous pensiez déjà tout savoir sur le Embarquez ensuite dans un espace dédié au Titanic… et pourtant… célèbre paquebot, et vivez la traversée, que vous soyez en première, seconde ou troisième Depuis 2012, La Cité de la Mer vous invite à classe. Tous les témoignages que vous embarquer dans un espace muséographique entendrez ici et là, qu’ils viennent des passagers original. Vous n’y trouverez ni objet, ni collection. ou des membres d’équipage, sont authentiques. La force et l’originalité du projet résident Moderne et interactif, cet espace se vit comme dans la scénographie. 15 grands musées et une expérience inédite, agrémentée de films, institutions traitant de l’émigration ont collaboré de photos, de témoignages et de décors au projet, dont Ellis Island à New York, Gênes, reconstitués de certaines pièces maîtresses du Bremerhaven, Halifax, Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo, paquebot. Anvers, Rotterdam. -

S/S Nevada, Guion Line

Page 1 of 2 Emigrant Ship databases Main Page >> Emigrant Ships S/S Nevada, Guion Line Search for ships by name or by first letter, browse by owner or builder Shipowner or Quick links Ships: Burden Built Dimensions A - B - C - D - E - F - G - H - I - J - K - L - operator M - N - O - P - Q - R - S - T - U - V - W - X - 3,121 1868 at Jarrow-on-Tyne by Palmer's 345.6ft x Y - Z - Æ - Ø - Å Guion Line Quick links Lines: gross Shipbuilding & Iron Co. Ltd. 43.4ft Allan Line - American Line - Anchor Line - Beaver Line - Canadian Pacific Line - Cunard Line - Dominion Line - Year Departure Arrival Remarks Guion Line - Hamburg America Line - Holland America Line - Inman Line - 1868 Oct. 17, launched Kroneline - Monarch Line - 1869 Feb. 2, maiden voyage Liverpool Norwegian America Line - National Line - Norddeutscher Lloyd - Red Star Line - - Queenstown - New York Ruger's American Line - Scandia Line - 1870 Liverpool New York Aug. 13 Liverpool & Great Wester Steam Scandinavian America Line - State Line - Swedish America Line - Temperley Line Ship Company - Norwegian American S.S. Co. - 1870 Liverpool New York Sept. 25 Liverpool & Great Wester Steam Thingvalla Line - White Star Line - Wilson Line Ship Company 1870 Liverpool New York Nov. 06 Liverpool & Great Wester Steam Agents & Shipping lines Ship Company Shipping lines, Norwegian agents, authorizations, routes and fleets. 1871 Liverpool New York Aug. 07 Agent DHrr. Blichfeldt & Co., Christiania Emigrant ship Arrivals 1871 Liverpool New York Sept. 17 Trond Austheim's database of emigrant ship arrivals around the world, 1870-1894. 1871 Liverpool New York Oct. -

Uitgeven in De Zeventiende Eeuw Staat Balthasar I Moretus Aan Het Hoofd Van De Plantijnse Drukkerij

WINTER 2018-2019 ONAANGEKONDIGDE TITELS TITRES INATTENDUS UNANNOUNCED TITLES BAI Balthasar Moretus and the Passion of Publishing In the seventeenth century, Balthasar Moretus I was master of the Plantin Press. The Baroque era was in full sway and proved highly influential on developments in the world of books. Balthasar succeeded in getting leading artists to work on his book designs. This included collaborating with Peter Paul Rubens on more than twenty projects. Even today, publishers still play the role of director in terms of book innovation, and the relationship between publisher and artist remains as important now as it was in the past. Balthasar Moretus and the Passion of Publishing introduces the reader to fascinating publishing projects that make us look at books in a new light. We learn how both publisher and artist are constantly reinventing the book together. Expo: 28/09/2018 - 06/01/2019, Museum Plantin Moretus, Antwerp (Baroque Book Design) E [BE] BAI Hardback,260x210 mm, Eng. ed., 88 p, Dec. 2018, € 22,50 ISBN: 9789085867708 (E) I03 - ART HISTORY Balthasar Moretus en de passie van het uitgeven In de zeventiende eeuw staat Balthasar I Moretus aan het hoofd van de Plantijnse drukkerij. De barok bloeit volop en dat heeft een grote invloed op hoe het boek evolueert. Balthasar betrekt vooraanstaande kunstenaars bij zijn boekontwerpen. Zo werkt hij voor meer dan twintig projecten met Peter Paul Rubens samen. Ook vandaag spelen uitgevers nog steeds de rol van regisseur in de vernieuwing van het boek, en ook nu is de relatie tussen uitgever en kunstenaars daarbij van belang. -

SSHSA Ephemera Collections Drawer Company/Line Ship Date Examplesshsa Line

Brochure Inventory - SSHSA Ephemera Collections Drawer Company/Line Ship Date ExampleSSHSA line A1 Adelaide S.S. Co. Moonta Admiral, Azure Seas, Emerald Seas, A1 Admiral Cruises, Inc. Stardancer 1960-1992 Enotria, Illiria, San Giorgio, San Marco, Ausonia, Esperia, Bernina,Stelvio, Brennero, Barletta, Messsapia, Grimani,Abbazia, S.S. Campidoglio, Espresso Cagliari, Espresso A1 Adriatica Livorno, corriere del est,del sud,del ovest 1949-1985 A1 Afroessa Lines Paloma, Silver Paloma 1989-1990 Alberni Marine A1 Transportation Lady Rose 1982 A1 Airline: Alitalia Navarino 1981 Airline: American A1 Airlines (AA) Volendam, Fairsea, Ambassador, Adventurer 1974 Bahama Star, Emerald Seas, Flavia, Stweard, Skyward, Southward, Federico C, Carla C, Boheme, Italia, Angelina Lauro, Sea A1 Airline: Delta Venture, Mardi Gras 1974 Michelangelo, Raffaello, Andrea, Franca C, Illiria, Fiorita, Romanza, Regina Prima, Ausonia, San Marco, San Giorgio, Olympia, Messapia, Enotria, Enricco C, Dana Corona, A1 Airline: Pan Am Dana Sirena, Regina Magna, Andrea C 1974 A1 Alaska Cruises Glacier Queen, Yukon Star, Coquitlam 1957-1962 Aleutian, Alaska, Yukon, Northwestern, A1 Alaska Steamship Co. Victoria, Alameda 1930-1941 A1 Alaska Ferry Malaspina, Taku, Matanuska, Wickersham 1963-1989 Cavalier, Clipper, Corsair, Leader, Sentinel, Prospector, Birgitte, Hanne, Rikke, Susanne, Partner, Pegasus, Pilgrim, Pointer, Polaris, Patriot, Pennant, Pioneer, Planter, Puritan, Ranger, Roamer, Runner Acadia, Saint John, Kirsten, Elin Horn, Mette Skou, Sygna, A1 Alcoa Steamship Co. Ferncape, -

Nr Kat EAN Code Artist Title Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data Premiery Repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl

nr kat EAN code artist title nośnik liczba nośników data premiery repertoire 19075816441 190758164410 '77 Bright Gloom Vinyl Longplay 33 1/3 2 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 19075816432 190758164328 '77 Bright Gloom CD Longplay 1 2018-04-27 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 9985848 5051099858480 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us CD Longplay 1 2015-10-30 HEAVYMETAL/HARDROCK 88697636262 886976362621 *NSYNC The Collection CD Longplay 1 2010-02-01 POP 88875025882 888750258823 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC CD Longplay 2 2014-11-11 POP 19075906532 190759065327 00 Fleming, John & Aly & Fila Future Sound of Egypt 550 CD Longplay 2 2018-11-09 DISCO/DANCE 88875143462 888751434622 12 Cellisten der Berliner Philharmoniker, Die Hora Cero CD Longplay 1 2016-06-10 CLASSICAL 88697919802 886979198029 2CELLOS 2CELLOS CD Longplay 1 2011-07-04 CLASSICAL 88843087812 888430878129 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 1 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88875052342 888750523426 2CELLOS Celloverse CD Longplay 2 2015-01-27 CLASSICAL 88725409442 887254094425 2CELLOS In2ition CD Longplay 1 2013-01-08 CLASSICAL 19075869722 190758697222 2CELLOS Let There Be Cello CD Longplay 1 2018-10-19 CLASSICAL 88883745419 888837454193 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD Video Longplay 1 2013-11-05 CLASSICAL 88985349122 889853491223 2CELLOS Score CD Longplay 1 2017-03-17 CLASSICAL 88985461102 889854611026 2CELLOS Score (Deluxe Edition) CD Longplay 2 2017-08-25 CLASSICAL 19075818232 190758182322 4 Times Baroque Caught in Italian Virtuosity CD Longplay 1 2018-03-09 CLASSICAL 88985330932 889853309320 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones -

Media® JUNE 1, 2002 / VOLUME 20 / ISSUE 23 / £3.95 / EUROS 6.5

Music Media® JUNE 1, 2002 / VOLUME 20 / ISSUE 23 / £3.95 / EUROS 6.5 THE MUCH ANTICIPATED NEW ALBUM 10-06-02 INCLUDES THE SINGLE 'HERE TO STAY' Avukr,m',L,[1] www.korntv.com wwwamymusweumpecun IMMORTam. AmericanRadioHistory.Com System Of A Down AerialscontainsThe forthcoming previously single unreleased released and July exclusive 1 Iostprophetscontent.Soldwww.systemofadown.com out AtEuropean radio now. tour. theFollowing lostprophets massive are thefakesoundofprogressnow success on tour in thethroughout UK and Europe.the US, featuredCatch on huge the new O'Neill single sportwear on"thefakesoundofprogress", MTVwww.lostprophets.com competitionEurope during running May. CreedOne Last Breath TheCommercialwww.creednet.com new single release from fromAmerica's June 17.biggest band. AmericanRadioHistory.Com TearMTVDrowning Europe Away Network Pool Priority! Incubuswww.drowningpool.comCommercialOn tour in Europe release now from with June Ozzfest 10. and own headlining shows. CommercialEuropean release festivals fromAre in JuneAugust.You 17.In? www.sonymusiceurope.cornSONY MUSIC EUROPE www.enjoyincubus.com Music Mediae JUNE 1, 2002 / VOLUME 20 / ISSUE 23 / £3.95 / EUROS 6.5 AmericanRadioHistory.Com T p nTA T_C ROCK Fpn"' THE SINGLE THE ALBUM A label owned by Poko Rekords Oy 71e um!010111, e -e- Number 1in Finland for 4 weeks Number 1in Finland Certified gold Certified gold, soon to become platinum Poko Rekords Oy, P.O. Box 483, FIN -33101 Tampere, Finland I Tel: +358 3 2136 800 I Fax: +358 3 2133 732 I Email: [email protected] I Website: www.poko.fi I www.pariskills.com Two rriot girls and a boy present: Album A label owned by Poko Rekords Oy \member of 7lit' EMI Cji0//p "..rriot" AmericanRadioHistory.Com UPFRONT Rock'snolonger by Emmanuel Legrand, Music & Media editor -in -chief Welcome to Music & Media's firstspecial inahard place issue of the year-an issue that should rock The fact that Ozzy your socks off. -

The Red Star Line and Jewish Immigrants

Saturday August 6, 2011 - Congregation for Humanistic Judaism – Unity Church, Sarasota THE RED STAR LINE Introduction There is no business than Sarasota business. It’s not from Irving Berlin, it’s my own interpretation. It is even not a quote, it is just what happened to me the previous years. By the way, Irving Berlin is one of the many who came to the United States with the Red Star Line from Antwerp. So, I am sincerely pleased to have been invited once again to Sarasota, a city which I am very fond of for many different reasons, both professional as private. I am even more moved because I found here a witness to a story that is very close to my heart. It is very close to my job as vice mayor for culture and tourism in the city of Antwerp as well. What I am referring to is the history of the Red Star Line shipping company and of immigration to the USA. We are opening a new museum on this topic next year in Antwerp: the Red Star Line|People on the Move museum. “The fact that we got out of Germany and then out of Antwerp, in the very last year that Red Star Line was running ships from Antwerp to the United States, was overwhelming” This is a quote from an interview we were able to make last year in Sarasota with Ms. Sonia Pressman Fuentes. Sonia and her parents and brother were among the many families that emigrated to the USA via Antwerp on a Red Star Line ship. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon