Steve Reich's New York Counterpoint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

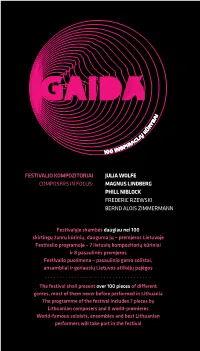

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

Back Cover Image

559682 rr Reich EU.qxp_559682 rr Reich EU 18/09/2020 08:44 Page 1 CMYK N 2 A 8 Steve X 6 Pl aying O 9 Time : S 5 5 R(bE. I19C36)H . 73:24 1 B o U A 8 f o l n l t o a Music for Two or More Pianos 10:57 h r (1964)* k i u 2 i g MERICAN LASSICS s l A C t e h h t c t o s Eight Lines for ensemble (1979/1983) 17:12 o n r 3 o m i i z n t Steve Reich is universally acknowledged e e p t S s d Vermont Counterpoint a h c i i T p s as one of the foremost exponents of n t u 9:33 for flutes and tape (1982) d s E E b o i n s l minimalism, arguably the most i u V e c c g n f New York Counterpoint l i p p d i s significant stylistic trend in late 20th- E r e h o r r L 4 12:07 e for clarinets and tape (1985) h f • o R c century music. This chronological i K = ca. 184 4:56 b r 5 o y m o i E r t t d e m = ca. 92 2:40 i a 6 survey shows how Reich’s innate i d I n n m . = ca. 184 3:31 C C c g e ൿ e curiosity has taken his work far beyond , n • , H a t & b a r s t such musical boundaries. -

An Exploration of Late Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Clarinet Repertoire

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 2021 An Exploration of Late Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Clarinet Repertoire Grace Talaski [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Talaski, Grace. "An Exploration of Late Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Clarinet Repertoire." (Spring 2021). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXPLORATION OF LATE TWENTIETH AND TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY CLARINET REPERTOIRE by Grace Talaski B.A., Albion College, 2017 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music School of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 2, 2021 Copyright by Grace Talaski, 2021 All Rights Reserved RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL AN EXPLORATION OF LATE TWENTIETH AND TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY CLARINET REPERTOIRE by Grace Talaski A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music Approved by: Dr. Eric Mandat, Chair Dr. Christopher Walczak Dr. Douglas Worthen Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale April 2, 2021 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF Grace Talaski, for the Master of Music degree in Performance, presented on April 2, 2021, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: AN EXPLORATION OF LATE TWENTIETH AND TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY CLARINET REPERTOIRE MAJOR PROFESSOR: Dr. Eric Mandat This is an extended program note discussing a selection of compositions featuring the clarinet from the mid-1980s through the present. -

Extended Play Review 25082018

EXTENDED PLAY (CITY RECITAL HALL) Not so much a new music tasting plate as a sumptuous multi-course banquet. by Angus McPherson on August 27, 2018 City Recital Hall, Sydney August 25, 2018 While the theatre world was immersed in the double-bill opening of Sydney Theatre Company’s The Harp in the South, another marathon performance was taking place in Sydney. Billed as a ‘micro festival’, Extended Play at City Recital Hall saw the city’s new music community descend on Angel Place for 12 straight hours of music. While I described it in a preview piece as part “tasting-plate”, the reality was more like a sumptuous multi-course banquet of music at which one could gorge until sated – and then gorge some more. Extended Play opened at midday with Elision Ensemble, whose set ranged from the swirling, sometimes brutal electronics of Aaron Cassidy’s The Wreck of Former Boundaries and colourful sonic textures of Richard Barrett’s world-line to Liza Lim’s complex, glittering solo The Su Song Star Map, performed by Graeme Jennings on violin. The next 12 hours revolved around the handful of main acts in the auditorium, with smaller-scale performances orbiting in spaces strewn across the venue, from the Level 1 Function Room to the bars and open spaces on Levels 2 and 3. Brisbane-based ensemble Topology, with guitarist Karin Schaupp, brought their incredibly moving collaboration with film-maker Trent Dalton, Love Stories, to the festival’s main stage next. Topology’s music interwove with interviews of patrons and staff at Brisbane’s 139 Club (now called 3rd Space), a drop-in centre offering support for city’s homeless and at-risk, in a deeply felt exploration of pain and love. -

ZGMTH - the Order of Things

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bangor University Research Portal The Order of Things. Analysis and Sketch Study in Two Works by Steve ANGOR UNIVERSITY Reich Bakker, Twila; ap Sion, Pwyll Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie DOI: 10.31751/1003 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/06/2019 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Bakker, T., & ap Sion, P. (2019). The Order of Things. Analysis and Sketch Study in Two Works by Steve Reich. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie, 16(1), 99-122. https://doi.org/10.31751/1003 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 09. Oct. 2020 ZGMTH - The Order of Things https://www.gmth.de/zeitschrift/artikel/1003.aspx Inhalt (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/inhalt.aspx) Impressum (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/impressum.aspx) Autorinnen und Autoren (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/autoren.aspx) Home (/home.aspx) Bakker, Twila / ap Siôn, Pwyll (2019): The Order of Things. -

Natal-Rn 2016

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE ESCOLA DE MÚSICA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM MÚSICA FERNANDO BUENO MENINO POSSIBILIDADES INTERPRETATIVAS ENVOLVENDO INSTRUMENTOS DE PERCUSSÃO E RECURSOS TECNOLÓGICOS NA OBRA CLAPPING MUSIC (1972), DE STEVE REICH NATAL-RN 2016 FERNANDO BUENO MENINO POSSIBILIDADES INTERPRETATIVAS ENVOLVENDO INSTRUMENTOS DE PERCUSSÃO E RECURSOS TECNOLÓGICOS NA OBRA CLAPPING MUSIC (1972), DE STEVE REICH Artigo apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, na linha de pesquisa – Processos e Dimensões da Produção Artística, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Cleber da Silveira Campos NATAL-RN 2016 Catalogação da Publicação na Fonte Biblioteca Setorial da Escola de Música M545p Menino, Fernando Bueno. Possibilidades interpretativas envolvendo instrumentos de percussão e recursos tecnológicos na obra Clapping Music (1972), de Steve Reich / Fernando Bueno Menino. – Natal, 2015. 52 f.: il.; 30 cm. Orientador: Cleber da Silveira Campos. Artigo (mestrado) – Escola de Música, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, 2015. 1. Música para percussão. 2. Música e Tecnologia. 3. Prática interpretativa (Música). I. Campos, Cleber da Silveira. II. Título. RN/BS/EMUFRN CDU 789 FERNANDO BUENO MENINO POSSIBILIDADES INTERPRETATIVAS ENVOLVENDO INSTRUMENTOS DE PERCUSSÃO E RECURSOS TECNOLÓGICOS NA OBRA CLAPPING MUSIC (1972), DE STEVE REICH Artigo apresentado ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Música da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música. APROVADA EM: ____/_____/____ BANCA EXAMINADORA __________________________________________________________________ PROF. DR. CLEBER DA SILVEIRA CAMPOS UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE (UFRN) ORIENTADOR ___________________________________________________________________ PROF. -

A Nonesuch Retrospective

STEVE REICH PHASES A N O nes U ch R etr O spective D isc One D isc T W O D isc T hree MUSIC FOR 18 MUSICIANS (1976) 67:42 DIFFERENT TRAINS (1988) 26:51 YOU ARE (VARIATIONS) (2004) 27:00 1. Pulses 5:26 1. America—Before the war 8:59 1. You are wherever your thoughts are 13:14 2. Section I 3:58 2. Europe—During the war 7:31 2. Shiviti Hashem L’negdi (I place the Eternal before me) 4:15 3. Section II 5:13 3. After the war 10:21 3. Explanations come to an end somewhere 5:24 4. Section IIIA 3:55 4. Ehmor m’aht, v’ahsay harbay (Say little and do much) 4:04 5. Section IIIB 3:46 Kronos Quartet 6. Section IV 6:37 David Harrington, violin Los Angeles Master Chorale 7. Section V 6:49 John Sherba, violin Grant Gershon, conductor 8. Section VI 4:54 Hank Dutt, viola Phoebe Alexander, Tania Batson, Claire Fedoruk, Rachelle Fox, 9. Section VII 4:19 Joan Jeanrenaud, cello Marie Hodgson, Emily Lin, sopranos 10. Section VIII 3:35 Sarona Farrell, Amy Fogerson, Alice Murray, Nancy Sulahian, 11. Section IX 5:24 TEHILLIM (1981) 30:29 Kim Switzer, Tracy Van Fleet, altos 12. Section X 1:51 4. Part I: Fast 11:45 Pablo Corá, Shawn Kirchner, Joseph Golightly, Sean McDermott, 13. Section XI 5:44 5. Part II: Fast 5:54 Fletcher Sheridan, Kevin St. Clair, tenors 14. Pulses 6:11 6. Part III: Slow 6:19 Geri Ratella, Sara Weisz, flutes 7. -

Signumclassics

143booklet 23/9/08 13:15 Page 1 ALSO AVAILABLE on signumclassics Different Trains Time for Marimba Steve Reich Daniella Ganeva The Smith Quartet SIGCD057 SIGCD064 Signum Classics are proud to release the Smith Quartet’s debut Time for Marimba explores the 20-th century Japanese repertoire for disc on Signum Records - Different Trains. The disc contains three marimba including music by five pre-eminent post-war composers. of Steve Reich’s most inspiring works: Triple Quartet for three string quartets, Reich’s personal dedication to the late Yehudi Menuhin, Duet, and the haunting Different Trains for string quartet and electronic tape. Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 143booklet 23/9/08 13:15 Page 3 Electric Counterpoint Electric Counterpoint Steve Reich 1. I Fast [6.51] 2. II Slow [3.22] 3. III Fast [4.33] 4. Tour de France Kraftwerk [5.25] 5. Radioactivity Kraftwerk [5.57] 6. Pocket Calculator Kraftwerk [6.44] 7. Carbon Copy Joby Burgess & Matthew Fairclough [5.14] 8. Temazcal Javier Alvarez [8.05] 9. Audiotectonics III Matthew Fairclough [3.47] Total Timings [49.55] Video: Temazcal [8.09] Powerplant Joby Burgess percussion Matthew Fairclough sound design Kathy Hinde visual artist The Elysian Quartet www.signumrecords.com 143booklet 23/9/08 13:15 Page 5 Electric Counterpoint Tour de France improvising with flute, electric guitar, cello and Carbon Copy Steve Reich (1936-) Ralf Hutter (1946-), Florian Schneider (1947-) vibraphone as the then Organisation, they Joby Burgess (1976-) and Matthew Fairclough I Fast II Slow III Fast and Karl Bartos (1952-) explored the sounds of the modern industrial (1970-) world, setting up their own studio, Kling Klang, Joby Burgess xylosynth Radioactivity which remains at a secret location in Dusseldorf. -

Minimalism and New Complexity in Solo Flute Repertoire by Twila Dawn Bakker Bachelor of Arts, Univer

Two Responses to Modernism: Minimalism and New Complexity in Solo Flute Repertoire by Twila Dawn Bakker Bachelor of Arts, University of Alberta, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Music Twila Dawn Bakker, 2011 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Two Responses to Modernism: Minimalism and New Complexity in Solo Flute Repertoire by Twila Dawn Bakker Bachelor of Arts, University of Alberta, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. Jonathan Goldman, School of Music Supervisor Dr. Michelle Fillion, School of Music Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Jonathan Goldman, School of Music Supervisor Dr. Michelle Fillion, School of Music Departmental Member Wind repertoire, especially for flute, has received little focused attention in the musicological world especially when compared with other instruments. This gap in scholarship is further exacerbated when the scope of time is narrowed to the last quarter of the twentieth century. Although Minimalism and New Complexity are – at least superficially – highly divergent styles of composition, they both exhibit aspects of a response to modernism. An examination of emblematic examples from the repertoire for solo flute (or recorder), specifically focusing on: Louis Andriessen’s Ende (1981); James Dillon’s Sgothan (1984), Brian Ferneyhough’s Carceri d’Invenzione IIb (1984), Superscripto (1981), and Unity Capsule (1975); Philip Glass’s Arabesque in Memoriam (1988); Henryk Górecki’s Valentine Piece (1996); and Steve Reich’s Vermont Counterpoint (1982), allows for the similarities in both genre’s response to modernism to be highlighted. -

Introduction to the DFT and Music for Pieces of Wood

Cyclic Rhythm and Rhythmic Qualities: Introduction to the DFT and an Application to Steve Reich’s Phase Music Jason Yust, Spring 2018 Much of Steve Reich’s music is based on repetition (often ad lib) of 1–2 measure rhythmic patterns. This is particularly true of his “phase” music from Piano Phase and Violin Phase in 1967 to Octet [Eight Lines] in 1979, and also much of the music of the 1980s, such as New York Counterpoint and Electric Counterpoint. The repetition of a consistent unit, one or two measures of 4/4 or 12/8, sometimes 10/8, with a basic pulse of and eighth-note or sixteenth, creates the framework of a rhythmic cycle. Rhythmic cycles invite an analogy with pitch classes, which are also cyclic. Hence, we can think of cyclic rhythms as “beat-class sets.” (This idea was first suggested by Milton Babbitt and built upon by Jeff Pressing, Richard Cohn, and John Roeder.1) Here, I will propose a method of analyzing cyclic rhythms using the DFT (discrete Fourier transform). This is, mathematically, the same method that is used for determining what frequencies are present in an audio signal. The differences when using this method to analyze beat-class sets are (1) Order of magnitude: the frequencies are much slower, so that they correspond to rhythmic periodicities rather than pitches, and (2) Simplifying assumptions: Rhythmic cycles include a relatively small number of eighth or sixteenth-notes (typically 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, or 24), and they are assumed to be perfectly periodic, meaning they could repeat indefinitely. -

L}-~ UW Modern Music Ensemble UW MUSIC

C(JW\~t\{t elISe N\ ~ 3 f\lIf\ r:g' SCHOOL OF MUSIC V!J\':!J UNIVERSITY of WASHINGTON Jo 1(0 l}-~ UW Modern Music Ensemble Cristi na L. Valdes, Director presents Steve Reich An 80th Birthday Celebration with special guests UW Percussion Ensemble Bonnie Whiting, Director Tuesday, December 6,2016 7:30 PM, Meany Theater UW MUSIC 2016-17 SEASON PROGRAM re-rnMf!..s, ValdL-s 2- PENDULUM MUSIC (1968, revised 1973) to, 'i/ Vijay Chalasani, Natalie Ham, Hexin Qiao, AlexanderTu Doug Niemela, technical director 3 DRUMMING, Part I(1971) I <r5 ~ 2. f University of Washington Percussion Ensemble David Gaskey, Aidan Gold, David Norgaard, Emerson Wahl Bonnie Whiting, director f TRIPLE QUARTET (1998) I'-f ~:3 '1 Erin Kelly &Halie Borror, violins / Vijay Chalasani, viola / Isabella Kodama, cello Matt Stearns, sound engineer INTERMISSION / CLAPPING MUSIC(1972) 5".2-7 Vijay Chalasani, Isabella Kodama, Hexin Qiao, AlexanderTu VERMONT COUNTERPOINT (1982) 9 ; L'S Gemma Goday Ofaz-Corralejo, flute Matt Stearns, sound engineer -3 RADIO REWRITE (2012) 19: 53 Erin Kelly &Halie Borror, violins Vijay Chalasani, viola Chris Young, cello . Natalie Ham, flute Alexander Tu, clarinet Emerson Wahl &Aidan Gold, vibraphones Hexin Qiao &Yimo Zhang, piano Tony Lefaive, electric bass Mario Alejandro Torres, conductor The University of Washington Modern Music Ensemble is excited to present an all-Steve Reich concert in celebration of the iconic 20th century composer's 80th birthday. Along with Philip Glass and Terry Riley, Reich's unique musical style and compositional voice helped shape the minimalistic movement. His techniques of phasing, tape loops, and rhythmic pulsing integrated into astatic harmony creating aworld of visceral thought that invites the mind to follow the process of unfolding music. -

2012–Ųjų Metų Gaidos Festivalis Taip Pat Pažymi Šią Reikšmingą Sukaktį Dedikuodamas Johnui Cage’Ui Dalį Savosios Programos

► Viena pagrindinių festivalio temų – erdvė (erdvė muzikoje, muzika erdvėje, spektriniai ir kiti erdvės aspektai) ► Festivalio kviestinis kompozitorius – Georgas Friedrichas Haasas, vienas įdomiausių ir labiausiai pripažintų šiandienos austrų kompozitorių ► Festivalis pristato specialius projektus Johno Cage’o – vieno įtakingiausių XX a. kūrėjų ir mąstytojų – 100 metų sukakčiai ► Atskiras dėmesys kitai amerikiečių įžymybei – Steve’ui Reich’ui ► Festivalio puošmena – kultiniai JAV ir Europos atlikėjai bei pasaulinio garso solistai ► Festivalyje dalyvaus geriausios Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos, skambės užsakyti kūriniai lietuvių kompozitoriams Festivalis GAIDA yra europinio naujosios muzikos kūrybos ir sklaidos tinklo Réseau Varése, remiamo Europos Komisijos programos Kultūra, narys. The GAIDA Festival is a member of the Réseau Varése, European network for the creation and promotion of new music, subsidized by the Culture Programme of the European Commission. TURINYS / CONTENT Programa / Programme .......................................................................................................2 100–asis Johno Cage’o gimtadienis / John Cage’s Centennial Anniversary .....6 Georgas Friedrichas Haasas / Georg Friedrich Hass .................................................10 Bang On A Can All-Stars (JAV / USA) ...............................................................................14 Plural Ensemble (Ispanija / Spain) ....................................................................................24 Lietuvos nacionalinis simfoninis