Contact: a Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) Citation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

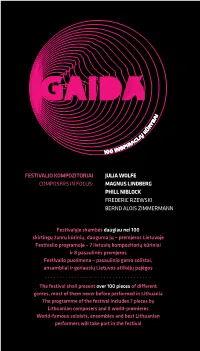

Julia Wolfe Magnus Lindberg Phill Niblock Frederic

FESTIVALIO KOMPOZITORIAI JULIA WOLFE COMPOSERS IN FOCUS: MAGNUS LINDBERG PHILL NIBLOCK FREDERIC RZEWSKI BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN Festivalyje skambės daugiau nei 100 skirtingų žanrų kūrinių, dauguma jų – premjeros Lietuvoje Festivalio programoje – 7 lietuvių kompozitorių kūriniai ir 8 pasaulinės premjeros Festivalio puošmena – pasaulinio garso solistai, ansambliai ir geriausių Lietuvos atlikėjų pajėgos The festival shall present over 100 pieces of different genres, most of them never before performed in Lithuania The programme of the festival includes 7 pieces by Lithuanian composers and 8 world-premieres World-famous soloists, ensembles and best Lithuanian performers will take part in the festival PB 1 PROGRAMA | TURINYS In Focus: Festivalio dėmesys taip pat: 6 JULIA WOLFE 18 FREDERIC RZEWSKI 10 MAGNUS LINDBERG 22 BERND ALOIS ZIMMERMANN 14 PHILL NIBLOCK 24 Spalio 20 d., šeštadienis, 20 val. 50 Spalio 26 d., penktadienis, 19 val. Vilniaus kongresų rūmai Šiuolaikinio meno centras LAURIE ANDERSON (JAV) SYNAESTHESIS THE LANGUAGE OF THE FUTURE IN FAHRENHEIT Florent Ghys. An Open Cage (2012) 28 Spalio 21 d., sekmadienis, 20 val. Frederic Rzewski. Les Moutons MO muziejus de Panurge (1969) SYNAESTHESIS Meredith Monk. Double Fiesta (1986) IN CELSIUS Julia Wolfe. Stronghold (2008) Panayiotis Kokoras. Conscious Sound (2014) Julia Wolfe. Reeling (2012) Alexander Schubert. Sugar, Maths and Whips Julia Wolfe. Big Beautiful Dark and (2011) Scary (2002) Tomas Kutavičius. Ritus rhythmus (2018, premjera)* 56 Spalio 27 d., šeštadienis, 19 val. Louis Andriessen. Workers Union (1975) Lietuvos nacionalinė filharmonija LIETUVOS NACIONALINIS 36 Spalio 24 d., trečiadienis, 19 val. SIMFONINIS ORKESTRAS Šiuolaikinio meno centras RŪTA RIKTERĖ ir ZBIGNEVAS Styginių kvartetas CHORDOS IBELHAUPTAS (fortepijoninis duetas) Dalyvauja DAUMANTAS KIRILAUSKAS COLIN CURRIE (kūno perkusija, (fortepijonas) Didžioji Britanija) Laurie Anderson. -

Back Cover Image

559682 rr Reich EU.qxp_559682 rr Reich EU 18/09/2020 08:44 Page 1 CMYK N 2 A 8 Steve X 6 Pl aying O 9 Time : S 5 5 R(bE. I19C36)H . 73:24 1 B o U A 8 f o l n l t o a Music for Two or More Pianos 10:57 h r (1964)* k i u 2 i g MERICAN LASSICS s l A C t e h h t c t o s Eight Lines for ensemble (1979/1983) 17:12 o n r 3 o m i i z n t Steve Reich is universally acknowledged e e p t S s d Vermont Counterpoint a h c i i T p s as one of the foremost exponents of n t u 9:33 for flutes and tape (1982) d s E E b o i n s l minimalism, arguably the most i u V e c c g n f New York Counterpoint l i p p d i s significant stylistic trend in late 20th- E r e h o r r L 4 12:07 e for clarinets and tape (1985) h f • o R c century music. This chronological i K = ca. 184 4:56 b r 5 o y m o i E r t t d e m = ca. 92 2:40 i a 6 survey shows how Reich’s innate i d I n n m . = ca. 184 3:31 C C c g e ൿ e curiosity has taken his work far beyond , n • , H a t & b a r s t such musical boundaries. -

Extended Play Review 25082018

EXTENDED PLAY (CITY RECITAL HALL) Not so much a new music tasting plate as a sumptuous multi-course banquet. by Angus McPherson on August 27, 2018 City Recital Hall, Sydney August 25, 2018 While the theatre world was immersed in the double-bill opening of Sydney Theatre Company’s The Harp in the South, another marathon performance was taking place in Sydney. Billed as a ‘micro festival’, Extended Play at City Recital Hall saw the city’s new music community descend on Angel Place for 12 straight hours of music. While I described it in a preview piece as part “tasting-plate”, the reality was more like a sumptuous multi-course banquet of music at which one could gorge until sated – and then gorge some more. Extended Play opened at midday with Elision Ensemble, whose set ranged from the swirling, sometimes brutal electronics of Aaron Cassidy’s The Wreck of Former Boundaries and colourful sonic textures of Richard Barrett’s world-line to Liza Lim’s complex, glittering solo The Su Song Star Map, performed by Graeme Jennings on violin. The next 12 hours revolved around the handful of main acts in the auditorium, with smaller-scale performances orbiting in spaces strewn across the venue, from the Level 1 Function Room to the bars and open spaces on Levels 2 and 3. Brisbane-based ensemble Topology, with guitarist Karin Schaupp, brought their incredibly moving collaboration with film-maker Trent Dalton, Love Stories, to the festival’s main stage next. Topology’s music interwove with interviews of patrons and staff at Brisbane’s 139 Club (now called 3rd Space), a drop-in centre offering support for city’s homeless and at-risk, in a deeply felt exploration of pain and love. -

ZGMTH - the Order of Things

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bangor University Research Portal The Order of Things. Analysis and Sketch Study in Two Works by Steve ANGOR UNIVERSITY Reich Bakker, Twila; ap Sion, Pwyll Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie DOI: 10.31751/1003 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/06/2019 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): Bakker, T., & ap Sion, P. (2019). The Order of Things. Analysis and Sketch Study in Two Works by Steve Reich. Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie, 16(1), 99-122. https://doi.org/10.31751/1003 Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 09. Oct. 2020 ZGMTH - The Order of Things https://www.gmth.de/zeitschrift/artikel/1003.aspx Inhalt (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/inhalt.aspx) Impressum (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/impressum.aspx) Autorinnen und Autoren (/zeitschrift/ausgabe-16-1-2019/autoren.aspx) Home (/home.aspx) Bakker, Twila / ap Siôn, Pwyll (2019): The Order of Things. -

Natal-Rn 2016

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE ESCOLA DE MÚSICA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM MÚSICA FERNANDO BUENO MENINO POSSIBILIDADES INTERPRETATIVAS ENVOLVENDO INSTRUMENTOS DE PERCUSSÃO E RECURSOS TECNOLÓGICOS NA OBRA CLAPPING MUSIC (1972), DE STEVE REICH NATAL-RN 2016 FERNANDO BUENO MENINO POSSIBILIDADES INTERPRETATIVAS ENVOLVENDO INSTRUMENTOS DE PERCUSSÃO E RECURSOS TECNOLÓGICOS NA OBRA CLAPPING MUSIC (1972), DE STEVE REICH Artigo apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, na linha de pesquisa – Processos e Dimensões da Produção Artística, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Cleber da Silveira Campos NATAL-RN 2016 Catalogação da Publicação na Fonte Biblioteca Setorial da Escola de Música M545p Menino, Fernando Bueno. Possibilidades interpretativas envolvendo instrumentos de percussão e recursos tecnológicos na obra Clapping Music (1972), de Steve Reich / Fernando Bueno Menino. – Natal, 2015. 52 f.: il.; 30 cm. Orientador: Cleber da Silveira Campos. Artigo (mestrado) – Escola de Música, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, 2015. 1. Música para percussão. 2. Música e Tecnologia. 3. Prática interpretativa (Música). I. Campos, Cleber da Silveira. II. Título. RN/BS/EMUFRN CDU 789 FERNANDO BUENO MENINO POSSIBILIDADES INTERPRETATIVAS ENVOLVENDO INSTRUMENTOS DE PERCUSSÃO E RECURSOS TECNOLÓGICOS NA OBRA CLAPPING MUSIC (1972), DE STEVE REICH Artigo apresentado ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Música da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música. APROVADA EM: ____/_____/____ BANCA EXAMINADORA __________________________________________________________________ PROF. DR. CLEBER DA SILVEIRA CAMPOS UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE (UFRN) ORIENTADOR ___________________________________________________________________ PROF. -

Review of Rethinking Reich, Edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll Ap Siôn (Oxford University Press, 2019) *

Review of Rethinking Reich, Edited by Sumanth Gopinath and Pwyll ap Siôn (Oxford University Press, 2019) * Orit Hilewicz NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hilewicz.php KEYWORDS: Steve Reich, analysis, politics DOI: 10.30535/mto.27.1.0 Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory [1] This past September, a scandal erupted on social media when a 2018 book excerpt was posted that showed a few lines from an interview with British photographer and music writer Val Wilmer. Wilmer recounted her meeting with Steve Reich in the early 1970s: I was talking about a person who was playing with him—who happened to be an African-American who was a friend of mine. I can tell you this now because I feel I must . we were talking and I mentioned this man, and [Reich] said, “Oh yes, well of course, he’s one of the only Blacks you can talk to.” So I said, “Oh really?” He said, “Blacks are geing ridiculous in the States now.” And I thought, “This is a man who’s just done this piece called Drumming which everybody cites as a great thing. He’s gone and ripped off stuff he’s heard in Ghana—and he’s telling me that Blacks are ridiculous in the States now.” I rest my case. Wouldn’t you be politicized? (Wilmer 2018, 60) Following recent revelations of racist and misogynist statements by central musical figures and calls for music scholarship to come to terms with its underlying patriarchal and white racial frame, (1) the new edited volume on Reich suggests directions music scholarship could take in order to examine the political, economic, and cultural environments in which musical works are composed, performed, and received. -

Reconsidering the Nineteenth-Century Potpourri: Johann Nepomuk Hummel’S Op

Reconsidering the Nineteenth-Century Potpourri: Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Op. 94 for Viola and Orchestra A document submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2018 by Fan Yang B. M., Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, 2008 M. M., Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, 2010 D. M. A. Candidacy, University of Cincinnati, 2013 Abstract The Potpourri for Viola and Orchestra, Op. 94 by Johann Nepomuk Hummel is available in a heavily abridged edition, entitled Fantasy, which causes confusions and problems. To clarify this misperception and help performers choose between the two versions, this document identifies the timeline and sources that exist for Hummel’s Op. 94 and compares the two versions of this work, focusing on material from the Potpourri missing in the Fantasy, to determine in what ways it contributes to the original work. In addition, by examining historical definitions and composed examples of the genre as well as philosophical ideas about the faithfulness to a work—namely, idea of the early nineteenth-century work concept, Werktreue—as well as counter arguments, this research aims to rationalize the choice to perform the Fantasy or Potpourri according to varied situations and purposes, or even to suggest adopting or adapting the Potpourri into a new version. Consequently, a final goal is to spur a reconsideration of the potpourri genre, and encourage performers and audiences alike to include it in their learning and programming. -

The Desert Music' at the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Next Wave Festival

Swarthmore College Works English Literature Faculty Works English Literature 1984 Steve Reich's 'The Desert Music' At The Brooklyn Academy Of Music's Next Wave Festival Peter Schmidt Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-english-lit Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Peter Schmidt. (1984). "Steve Reich's 'The Desert Music' At The Brooklyn Academy Of Music's Next Wave Festival". William Carlos Williams Review. Volume 10, Issue 2. 25-25. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-english-lit/211 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Literature Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 25 Steve Reich's The Desert Music at the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Next Wave Festival "For music is changing in character today as it has always done." -WCW (SE 57) On October 25-27, the 1984 Next Wave Festival at the Brooklyn Academy of Music presented the American premiere of Steve Reich's The Desert Music, a piece for chorus and orchestra setting to music excerpts from three poems by William Carlos Williams, "Asphodel, That Greeny Flower," "The Orchestra," and his translation of Theocritus' Idyl I. Michael Tilson Thomas conducted the Brooklyn Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra and chorus, and he, the musicians, and the composer received standing ovations after the performances. Steve Reich is one of this country's most promising young composers. -

A Nonesuch Retrospective

STEVE REICH PHASES A N O nes U ch R etr O spective D isc One D isc T W O D isc T hree MUSIC FOR 18 MUSICIANS (1976) 67:42 DIFFERENT TRAINS (1988) 26:51 YOU ARE (VARIATIONS) (2004) 27:00 1. Pulses 5:26 1. America—Before the war 8:59 1. You are wherever your thoughts are 13:14 2. Section I 3:58 2. Europe—During the war 7:31 2. Shiviti Hashem L’negdi (I place the Eternal before me) 4:15 3. Section II 5:13 3. After the war 10:21 3. Explanations come to an end somewhere 5:24 4. Section IIIA 3:55 4. Ehmor m’aht, v’ahsay harbay (Say little and do much) 4:04 5. Section IIIB 3:46 Kronos Quartet 6. Section IV 6:37 David Harrington, violin Los Angeles Master Chorale 7. Section V 6:49 John Sherba, violin Grant Gershon, conductor 8. Section VI 4:54 Hank Dutt, viola Phoebe Alexander, Tania Batson, Claire Fedoruk, Rachelle Fox, 9. Section VII 4:19 Joan Jeanrenaud, cello Marie Hodgson, Emily Lin, sopranos 10. Section VIII 3:35 Sarona Farrell, Amy Fogerson, Alice Murray, Nancy Sulahian, 11. Section IX 5:24 TEHILLIM (1981) 30:29 Kim Switzer, Tracy Van Fleet, altos 12. Section X 1:51 4. Part I: Fast 11:45 Pablo Corá, Shawn Kirchner, Joseph Golightly, Sean McDermott, 13. Section XI 5:44 5. Part II: Fast 5:54 Fletcher Sheridan, Kevin St. Clair, tenors 14. Pulses 6:11 6. Part III: Slow 6:19 Geri Ratella, Sara Weisz, flutes 7. -

Chamber Music Concert

2009-2010 presents UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON WIND ENSEMBLE Timothy Salzman, conductor CHAMBER MUSIC CONCERT October 25, 2009 1:30 PM Brechemin Auditorium PROGRAM BRAIN RUBBISH (2006/7) ............................................................................... CHRISTIAN LINDBERG (b. 1958) Gary Brattin, conductor Eric Smedley* / Angela Zumbow* / Joseph Sullivan / Joshua Gailey / Leah Miyamoto, trumpet Kenji Ulmer* / Christopher Sibbers / Alison Farley, horn Masa Ohtake* / Sam Elliot / Man-Kit Iong / Zach Roberts, trombone Danny Helseth, euphonium Curtis Peacock* / Seth Tompkins, tuba *brass quintet soloists EIGHT LINES (1983) .................................................................................................... STEVE REICH (b. 1936) Vu Nguyen, conductor Chung-Lin Lee / Maggie Stapleton, flute & piccolo Jacob Bloom / Kirsten Cummings / Geoffrey Larson, clarinet & bass clarinet Akiko Iguchi / Mayumi Tayake, piano Katy Balatero / Elizabeth Knighton / Kouki Tanaka / Matthew Wu, violin T. J. Pierce / Andrew Schirmer, viola Karen Helseth / Erica Klein, cello SHARPENED STICK (2000) ........................................................................... BRETT WILLIAM DIETZ (b. 1972) Timothy Salzman, conductor Jennifer Wagner / Chris Lennard / Melanie Stambaugh / Lacey Brown / Chia-Hao Hsieh MOGGIN’ ALONG Fr’ forty years next Easter day, An’ then children Him and me in wind and weather Come till we have eight Have been a-gittin’ bent ‘n; gray As han’some babes as ever growed Moggin’ along together. To walk beside a mother’s knee, They helped me bear it all, y’ see. We’re not so very old, of course, It ain’t been nothin’ else But still, we ain’t so awful spry, But scrub an’ rub’ an’ bake, and stew As when we went to singin’-school The hull, hull time over stove or tub Afoot and ‘cross lots, him and I, No time to rest as men folk do. -

Minimalism and New Complexity in Solo Flute Repertoire by Twila Dawn Bakker Bachelor of Arts, Univer

Two Responses to Modernism: Minimalism and New Complexity in Solo Flute Repertoire by Twila Dawn Bakker Bachelor of Arts, University of Alberta, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Music Twila Dawn Bakker, 2011 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Two Responses to Modernism: Minimalism and New Complexity in Solo Flute Repertoire by Twila Dawn Bakker Bachelor of Arts, University of Alberta, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. Jonathan Goldman, School of Music Supervisor Dr. Michelle Fillion, School of Music Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Jonathan Goldman, School of Music Supervisor Dr. Michelle Fillion, School of Music Departmental Member Wind repertoire, especially for flute, has received little focused attention in the musicological world especially when compared with other instruments. This gap in scholarship is further exacerbated when the scope of time is narrowed to the last quarter of the twentieth century. Although Minimalism and New Complexity are – at least superficially – highly divergent styles of composition, they both exhibit aspects of a response to modernism. An examination of emblematic examples from the repertoire for solo flute (or recorder), specifically focusing on: Louis Andriessen’s Ende (1981); James Dillon’s Sgothan (1984), Brian Ferneyhough’s Carceri d’Invenzione IIb (1984), Superscripto (1981), and Unity Capsule (1975); Philip Glass’s Arabesque in Memoriam (1988); Henryk Górecki’s Valentine Piece (1996); and Steve Reich’s Vermont Counterpoint (1982), allows for the similarities in both genre’s response to modernism to be highlighted. -

Clever Children: the Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music?

Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music Author Carter, David Published 2009 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Queensland Conservatorium DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1356 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367632 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Clever Children: The Sons and Daughters of Experimental Music? David Carter B.Music / Music Technology (Honours, First Class) Queensland Conservatorium Griffith University A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy 19 June 2008 Keywords Contemporary Music; Dance Music; Disco; DJ; DJ Spooky; Dub; Eight Lines; Electronica; Electronic Music; Errata Erratum; Experimental Music; Hip Hop; House; IDM; Influence; Techno; John Cage; Minimalism; Music History; Musicology; Rave; Reich Remixed; Scanner; Surface Noise. i Abstract In the late 1990s critics, journalists and music scholars began referring to a loosely associated group of artists within Electronica who, it was claimed, represented a new breed of experimentalism predicated on the work of composers such as John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Steve Reich. Though anecdotal evidence exists, such claims by, or about, these ‘Clever Children’ have not been adequately substantiated and are indicative of a loss of history in relation to electronic music forms (referred to hereafter as Electronica) in popular culture. With the emergence of the Clever Children there is a pressing need to redress this loss of history through academic scholarship that seeks to document and critically reflect on the rhizomatic developments of Electronica and its place within the history of twentieth century music.