Examining the Competition Between Conifer and Angiosperm Trees Author(S): Timothy J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Approved Plant List 10/04/12

FLORIDA The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago, the second best time to plant a tree is today. City of Sunrise Approved Plant List 10/04/12 Appendix A 10/4/12 APPROVED PLANT LIST FOR SINGLE FAMILY HOMES SG xx Slow Growing “xx” = minimum height in Small Mature tree height of less than 20 feet at time of planting feet OH Trees adjacent to overhead power lines Medium Mature tree height of between 21 – 40 feet U Trees within Utility Easements Large Mature tree height greater than 41 N Not acceptable for use as a replacement feet * Native Florida Species Varies Mature tree height depends on variety Mature size information based on Betrock’s Florida Landscape Plants Published 2001 GROUP “A” TREES Common Name Botanical Name Uses Mature Tree Size Avocado Persea Americana L Bahama Strongbark Bourreria orata * U, SG 6 S Bald Cypress Taxodium distichum * L Black Olive Shady Bucida buceras ‘Shady Lady’ L Lady Black Olive Bucida buceras L Brazil Beautyleaf Calophyllum brasiliense L Blolly Guapira discolor* M Bridalveil Tree Caesalpinia granadillo M Bulnesia Bulnesia arboria M Cinnecord Acacia choriophylla * U, SG 6 S Group ‘A’ Plant List for Single Family Homes Common Name Botanical Name Uses Mature Tree Size Citrus: Lemon, Citrus spp. OH S (except orange, Lime ect. Grapefruit) Citrus: Grapefruit Citrus paradisi M Trees Copperpod Peltophorum pterocarpum L Fiddlewood Citharexylum fruticosum * U, SG 8 S Floss Silk Tree Chorisia speciosa L Golden – Shower Cassia fistula L Green Buttonwood Conocarpus erectus * L Gumbo Limbo Bursera simaruba * L -

Vegetation Benchmarks Rainforest and Related Scrub

Vegetation Benchmarks Rainforest and related scrub Eucryphia lucida Vegetation Condition Benchmarks version 1 Rainforest and Related Scrub RPW Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland: Sphagnum peatland facies Community Description: Athrotaxis cupressoides (5–8 m) forms small woodland patches or appears as copses and scattered small trees. On the Central Plateau (and other dolerite areas such as Mount Field), broad poorly– drained valleys and small glacial depressions may contain scattered A. cupressoides trees and copses over Sphagnum cristatum bogs. In the treeless gaps, Sphagnum cristatum is usually overgrown by a combination of any of Richea scoparia, R. gunnii, Baloskion australe, Epacris gunnii and Gleichenia alpina. This is one of three benchmarks available for assessing the condition of RPW. This is the appropriate benchmark to use in assessing the condition of the Sphagnum facies of the listed Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland community (Schedule 3A, Nature Conservation Act 2002). Benchmarks: Length Component Cover % Height (m) DBH (cm) #/ha (m)/0.1 ha Canopy 10% - - - Large Trees - 6 20 5 Organic Litter 10% - Logs ≥ 10 - 2 Large Logs ≥ 10 Recruitment Continuous Understorey Life Forms LF code # Spp Cover % Immature tree IT 1 1 Medium shrub/small shrub S 3 30 Medium sedge/rush/sagg/lily MSR 2 10 Ground fern GF 1 1 Mosses and Lichens ML 1 70 Total 5 8 Last reviewed – 2 November 2016 Tasmanian Vegetation Monitoring and Mapping Program Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment http://www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au/tasveg RPW Athrotaxis cupressoides open woodland: Sphagnum facies Species lists: Canopy Tree Species Common Name Notes Athrotaxis cupressoides pencil pine Present as a sparse canopy Typical Understorey Species * Common Name LF Code Epacris gunnii coral heath S Richea scoparia scoparia S Richea gunnii bog candleheath S Astelia alpina pineapple grass MSR Baloskion australe southern cordrush MSR Gleichenia alpina dwarf coralfern GF Sphagnum cristatum sphagnum ML *This list is provided as a guide only. -

Edition 2 from Forest to Fjaeldmark the Vegetation Communities Highland Treeless Vegetation

Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark The Vegetation Communities Highland treeless vegetation Richea scoparia Edition 2 From Forest to Fjaeldmark 1 Highland treeless vegetation Community (Code) Page Alpine coniferous heathland (HCH) 4 Cushion moorland (HCM) 6 Eastern alpine heathland (HHE) 8 Eastern alpine sedgeland (HSE) 10 Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) 12 Western alpine heathland (HHW) 13 Western alpine sedgeland/herbland (HSW) 15 General description Rainforest and related scrub, Dry eucalypt forest and woodland, Scrub, heathland and coastal complexes. Highland treeless vegetation communities occur Likewise, some non-forest communities with wide within the alpine zone where the growth of trees is environmental amplitudes, such as wetlands, may be impeded by climatic factors. The altitude above found in alpine areas. which trees cannot survive varies between approximately 700 m in the south-west to over The boundaries between alpine vegetation communities are usually well defined, but 1 400 m in the north-east highlands; its exact location depends on a number of factors. In many communities may occur in a tight mosaic. In these parts of Tasmania the boundary is not well defined. situations, mapping community boundaries at Sometimes tree lines are inverted due to exposure 1:25 000 may not be feasible. This is particularly the or frost hollows. problem in the eastern highlands; the class Eastern alpine vegetation (undifferentiated) (HUE) is used in There are seven specific highland heathland, those areas where remote sensing does not provide sedgeland and moorland mapping communities, sufficient resolution. including one undifferentiated class. Other highland treeless vegetation such as grasslands, herbfields, A minor revision in 2017 added information on the grassy sedgelands and wetlands are described in occurrence of peatland pool complexes, and other sections. -

Native Plants Sixth Edition Sixth Edition AUSTRALIAN Native Plants Cultivation, Use in Landscaping and Propagation

AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS SIXTH EDITION SIXTH EDITION AUSTRALIAN NATIVE PLANTS Cultivation, Use in Landscaping and Propagation John W. Wrigley Murray Fagg Sixth Edition published in Australia in 2013 by ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Reed New Holland an imprint of New Holland Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd Sydney • Auckland • London • Cape Town Many people have helped us since 1977 when we began writing the first edition of Garfield House 86–88 Edgware Road London W2 2EA United Kingdom Australian Native Plants. Some of these folk have regrettably passed on, others have moved 1/66 Gibbes Street Chatswood NSW 2067 Australia to different areas. We endeavour here to acknowledge their assistance, without which the 218 Lake Road Northcote Auckland New Zealand Wembley Square First Floor Solan Road Gardens Cape Town 8001 South Africa various editions of this book would not have been as useful to so many gardeners and lovers of Australian plants. www.newhollandpublishers.com To the following people, our sincere thanks: Steve Adams, Ralph Bailey, Natalie Barnett, www.newholland.com.au Tony Bean, Lloyd Bird, John Birks, Mr and Mrs Blacklock, Don Blaxell, Jim Bourner, John Copyright © 2013 in text: John Wrigley Briggs, Colin Broadfoot, Dot Brown, the late George Brown, Ray Brown, Leslie Conway, Copyright © 2013 in map: Ian Faulkner Copyright © 2013 in photographs and illustrations: Murray Fagg Russell and Sharon Costin, Kirsten Cowley, Lyn Craven (Petraeomyrtus punicea photograph) Copyright © 2013 New Holland Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd Richard Cummings, Bert -

Agathis Macrophylla Araucariaceae (Lindley) Masters

Agathis macrophylla (Lindley) Masters Araucariaceae LOCAL NAMES English (pacific kauri); Fijian (da‘ua,dakua dina,makadri,makadre,takua makadre,dakua,dakua makadre) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Agathis macrophylla is a tall tree typically to about 30–40 m tall, 3 m in bole diameter, with a broad canopy of up to 36 m diameter. Branches may be erect to horizontal and massive. Mature specimens have wide, spreading root systems whereas seedlings and young specimens have a vigorous taproot with one or more whorls of lateral roots. Leaves simple, entire, elliptic to lanceolate, leathery, and dark green, and shiny above and often glaucous below; about 7–15 cm long and 2–3.5 cm wide, with many close inconspicuous parallel veins. The leaves taper to a more or less pointed tip, rounded at the base, with the margins curved down at the edge. Petioles short, from almost sessile up to 5 mm long. Cones egg-shaped at the end of the first year, about 5 cm long, and 3 cm in diameter, more or less round at the end of the second year, 8–10 cm in diameter. Female cones much larger than males, globular, on thick woody stalks, green, slightly glaucous, turning brownish during ripening. Seeds brown, small, ovoid to globose, flattened, winged, and attached to a triangular cone scale about 2.5 cm across. BIOLOGY Pacific kauri is monoecious and produces cones instead of flowers. The first female cones begin to be produced at about 10 years old and take up to 2 years to mature (more often in 12-15 months). -

Podocarpus Totara

Mike Marden and Chris Phillips [email protected] TTotaraotara Podocarpus totara INTRODUCTION AND METHODS Reasons for planting native trees include the enhancement of plant and animal biodiversity for conservation, establishment of a native cover on erosion-prone sites, improvement of water quality by revegetation of riparian areas and management for production of high quality timber. Signifi cant areas of the New Zealand landscape, both urban and rural, are being re-vegetated using native species. Many such plantings are on open sites where the aim is to quickly achieve canopy closure and often includes the planting of a mixture of shrubs and tree species concurrently. Previously, data have been presented showing the potential above- and below-ground growth performance of eleven native plant species considered typical early colonisers of bare ground, particularly in riparian areas (http://icm.landcareresearch.co.nz/research/land/Trial1results.asp). In this current series of posters we present data on the growth performance of six native conifer (kauri, rimu, totara, matai, miro, kahikatea) and two broadleaved hardwood (puriri, titoki) species most likely to succeed the early colonising species to become a major component in mature stands of indigenous forest (http://icm.landcareresearch.co.nz/research/land/ Trial2.asp). Data on the potential above- and below-ground early growth performance of colonising shrubby species together with that of conifer and broadleaved species will help land managers and community groups involved in re-vegetation projects in deciding the plant spacing and species mix most appropriate for the scale of planting and best suited to site conditions. Data are from a trial established in 2006 to assess the relative growth performance of native conifer and broadleaved hardwood tree species. -

Morphology and Anatomy of Pollen Cones and Pollen in Podocarpus Gnidioides Carrière (Podocarpaceae, Coniferales)

1 2 Bull. CCP 4 (1): 36-48 (6.2015) V.M. Dörken & H. Nimsch Morphology and anatomy of pollen cones and pollen in Podocarpus gnidioides Carrière (Podocarpaceae, Coniferales) Abstract Podocarpus gnidioides is one of the rarest Podocarpus species in the world, and can rarely be found in collections; fertile material especially is not readily available. Until now no studies about its reproductive structures do exist. By chance a 10-years-old individual cultivated as a potted plant in the living collection of the second author produced 2014 pollen cones for the first time. Pollen cones of Podocarpus gnidioides have been investigated with microtome technique and SEM. Despite the isolated systematic position of Podocarpus gnidioides among the other New Caledonian Podocarps, it shows no unique features in morphology and anatomy of its hyposporangiate pollen cones and pollen. Both the pollen cones and the pollen are quite small and belong to the smallest ones among recent Podocarpus-species. The majority of pollen cones are unbranched but also a few branched ones are found, with one or two lateral units each of them developed from different buds, so that the base of each lateral cone-axis is also surrounded by bud scales. This is a great difference to other coniferous taxa with branched pollen cones e.g. Cephalotaxus (Taxaceae), where the whole “inflorescence” is developed from a single bud. It could be shown, that the pollen presentation in the erect pollen cones of Podocarpus gnidioides is secondary. However, further investigations with more specimens collected in the wild will be necessary. Key words: Podocarpaceae, Podocarpus, morphology, pollen, cone 1 Introduction Podocarpus gnidioides is an evergreen New Caledonian shrub, reaching up to 2 m in height (DE LAUBENFELS 1972; FARJON 2010). -

Serenity Pervades a Chinese Garden of the Ming Dynasty, for This Is a Place of Retreat from the Doings of Humankind

Serenity pervades a Chinese garden of the Ming dynasty, for this is a place of retreat from the doings of humankind. It is where the functionary of the kingdom could indulge his "longing for mountains and water" without turning his back on his unrelenting obligations to state and family. Yet serenity is only the first of infinite layers that reveal themselves. The object of the garden is to capture all the elements of the natural landscape--mountains, rivers, lakes, trees, valleys, hills--and, by bringing them together in a small space, to concentrate the life force, the qi, that animates them. It is a harmony of contrasts, of dark and light, solid and empty, hard and soft, straight and undulating, yin and yang. This place was created to be savoured ever a lifetime. New meanings would be found in the symbolic objects and plants, new pictures seen as shadows placed across the rocks. The garden unfolded itself slowly. In this site, the Garden comes to life. The Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden in Vancouver, British Columbia is the only full-sized classical Chinese garden outside China and though it was built in the 1980s, it employed the ancient techniques of the originals. For the architect, the botanist, the student of history, the lover of beauty, this site provides insights into the subtle wonders to be found within the walls of this living treasure. A Walk Through the Garden The Garden's Layers of Meaning Originally designed by Taoist poets, classical gardens were meant to create an atmosphere of tranquility for contemplation and inspiration. -

Pollination Drop in Relation to Cone Morphology in Podocarpaceae: a Novel Reproductive Mechanism Author(S): P

Pollination Drop in Relation to Cone Morphology in Podocarpaceae: A Novel Reproductive Mechanism Author(s): P. B. Tomlinson, J. E. Braggins, J. A. Rattenbury Source: American Journal of Botany, Vol. 78, No. 9 (Sep., 1991), pp. 1289-1303 Published by: Botanical Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2444932 . Accessed: 23/08/2011 15:47 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Botanical Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Botany. http://www.jstor.org AmericanJournal of Botany 78(9): 1289-1303. 1991. POLLINATION DROP IN RELATION TO CONE MORPHOLOGY IN PODOCARPACEAE: A NOVEL REPRODUCTIVE MECHANISM' P. B. TOMLINSON,2'4 J. E. BRAGGINS,3 AND J. A. RATTENBURY3 2HarvardForest, Petersham, Massachusetts 01366; and 3Departmentof Botany, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand Observationof ovulatecones at thetime of pollinationin the southernconiferous family Podocarpaceaedemonstrates a distinctivemethod of pollencapture, involving an extended pollinationdrop. Ovules in all generaof the family are orthotropousand singlewithin the axil of each fertilebract. In Microstrobusand Phyllocladusovules are-erect (i.e., the micropyle directedaway from the cone axis) and are notassociated with an ovule-supportingstructure (epimatium).Pollen in thesetwo genera must land directly on thepollination drop in theway usualfor gymnosperms, as observed in Phyllocladus.In all othergenera, the ovule is inverted (i.e., the micropyleis directedtoward the cone axis) and supportedby a specializedovule- supportingstructure (epimatium). -

The New Zealand Beeches : Establishment, Growth and Management / Mark Smale, David Bergin and Greg Steward, Photography by Ian Platt

Mark Smale, David K ....,.,. and Greg ~t:~·wa11.r Photography by lan P Reproduction of material in this Bulletin for non-commercial purposes is welcomed, providing there is appropriate acknowledgment of its source. To obtain further copies of this publication, or for information about other publications, please contact: Publications Officer Private Bag 3020 Rotorua New Zealand Telephone: +64 7 343 5899 Fac.rimile: +64 7 348 0952 E-nraif. publications@scionresearch .com !Pebsite: www.scionresearch.com National Library of New Zealand Cataloguing-in-Publication data The New Zealand beeches : establishment, growth and management / Mark Smale, David Bergin and Greg Steward, Photography by Ian Platt. (New Zealand Indigenous Tree Bulletin, 1176-2632; no.6) Includes bibliographic references. 978-0-478-11018-0 1. trees. 2. Forest management-New Zealand. 3. Forests and forestry-New Zealand. 1. Smale, Mark, 1954- ll. Bergin, David, 1954- ill. Steward, Greg, 1961- IV. Series. V. New Zealand Forese Research Institute. 634.90993-dc 22 lSSN 1176-2632 ISBN 978-0-478-11038-3 ©New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited 2012 Production Team Teresa McConcbie, Natural Talent Design - design and layout Ian Platt- photography Sarah Davies, Richard Moberly, Scion - printing and production Paul Charters - editing DISCLAIMER In producing this Bulletin reasonable care has been taAren lo mmre tbat all statements represent the best infornJation available. Ht~~vever, tbe contents of this pt1blicatio11 are not i11tended to be a substitute for s,Pecific specialist advice on at!} matter and should not be relied on for that pury~ose. NEW ZEALAND FOREST RESEARCH INSTITUTE L!JWJTED mtd its emplqyees shall not be liable on at.ry ground for a'!)l lost, damage, or liabili!J inrorred as a direct or indirect result of at!J reliance l{y a'!)l person upon informatiou contained or opinions expressed in this tvork. -

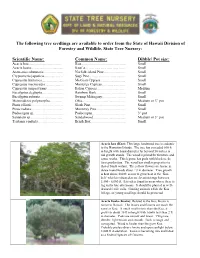

The Following Tree Seedlings Are Available to Order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery

The following tree seedlings are available to order from the State of Hawaii Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State Tree Nursery: Scientific Name: Common Name: Dibble/ Pot size: Acacia koa……………………… Koa……………………………….. Small Acacia koaia……………………... Koai’a……………………………. Small Araucaria columnaris…………….. Norfolk-island Pine……………… Small Cryptomeria japonica……………. Sugi Pine………………………… Small Cupressus lusitanica……………... Mexican Cypress………………… Small Cupressus macrocarpa…………… Monterey Cypress……………….. Small Cupressus simpervirens………….. Italian Cypress…………………… Medium Eucalyptus deglupta……………… Rainbow Bark……………………. Small Eucalyptus robusta……………….. Swamp Mahogany……………….. Small Metrosideros polymorpha……….. Ohia……………………………… Medium or 3” pot Pinus elliotii……………………… Slash Pine………………………... Small Pinus radiata……………………... Monterey Pine…………………… Small Podocarpus sp……………………. Podocarpus………………………. 3” pot Santalum sp……………………… Sandalwood……………………… Medium or 3” pot Tristania conferta………………… Brush Box………………………... Small Acacia koa (Koa): This large hardwood tree is endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. The tree has exceeded 100 ft in height with basal diameter far beyond 50 inches in old growth stands. The wood is prized for furniture and canoe works. This legume has pods with black seeds for reproduction. The wood has similar properties to that of black walnut. The yellow flowers are borne in dense round heads about 2@ in diameter. Tree growth is best above 800 ft; seems to grow best in the ‘Koa belt’ which is situated at an elevation range between 3,500 - 6,000 ft. It is often found in areas where there is fog in the late afternoons. It should be planted in well- drained fertile soils. Grazing animals relish the Koa foliage, so young seedlings should be protected Acacia koaia (Koaia): Related to the Koa, Koaia is native to Hawaii. The leaves and flowers are much the same as Koa. -

Podocarpus Falcatus Podocarpus1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-492 October 1994 Podocarpus falcatus Podocarpus1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Podocarpus falcatus grows very slowly, probably to 40 feet or more in an open landscape, but has reached 100 feet in its native habitat (Fig. 1). The two-inch long, blue foliage borne on a rigid pyramidal canopy would make a striking specimen in any landscape. It casts dense shade when branched to the ground, so no grass grows beneath it. It lends a rigid, formal effect to any landscape due to the stiff, horizontal branches, but the blue foliage softens this effect. It could be used as a specimen or as a screen planted 10 to 15 feet apart. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Podocarpus falcatus Figure 1. Middle-aged Podocarpus. Pronunciation: poe-doe-KAR-pus fal-KAY-tus Common name(s): Podocarpus Family: Podocarpaceae Crown shape: pyramidal USDA hardiness zones: 10 through 11 (Fig. 2) Crown density: dense Origin: not native to North America Growth rate: medium Uses: hedge; recommended for buffer strips around Texture: fine parking lots or for median strip plantings in the highway; screen; specimen; no proven urban tolerance Foliage Availability: grown in small quantities by a small number of nurseries Leaf arrangement: opposite/subopposite (Fig. 3) Leaf type: simple DESCRIPTION Leaf margin: entire Leaf shape: linear Height: 30 to 40 feet Leaf venation: parallel Spread: 25 to 35 feet Leaf type and persistence: evergreen Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a Leaf blade length: less than 2 inches regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more Leaf color: blue or blue-green; green or less identical crown forms 1.