Who Eats Who? Beachy Food Chains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrient Bioextraction L

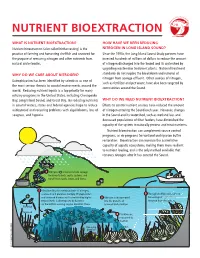

soun nd d s sla tu i d g y n o NUTRIENT BIOEXTRACTION l WHAT IS NUTRIENT BIOEXTRACTION? HOW HAVE WE BEEN REDUCING Nutrient bioextraction (also called bioharvesting) is the NITROGEN IN LONG ISLAND SOUND? practice of farming and harvesting shellfish and seaweed for Since the 1990s, the Long Island Sound Study partners have the purpose of removing nitrogen and other nutrients from invested hundreds of millions of dollars to reduce the amount natural water bodies. of nitrogen discharged into the Sound and its watershed by upgrading wastewater treatment plants. National treatment WHY DO WE CARE ABOUT NITROGEN? standards do not require the breakdown and removal of nitrogen from sewage effluent. Other sources of nitrogen, Eutrophication has been identified by scientists as one of such as fertilizer and pet waste, have also been targeted by the most serious threats to coastal environments around the communities around the Sound. world. Reducing nutrient inputs is a top priority for many estuary programs in the United States, including Chesapeake Bay, Long Island Sound, and Great Bay. By reducing nutrients WHY DO WE NEED NUTRIENT BIOEXTRACTION? in coastal waters, states and federal agencies hope to reduce Efforts to control nutrient sources have reduced the amount widespread and recurring problems with algal blooms, loss of of nitrogen entering the Sound each year. However, changes seagrass, and hypoxia. in the Sound and its watershed, such as wetland loss and decreased populations of filter feeders, have diminished the capacity of the system to naturally process and treat nutrients. Nutrient bioextraction can complement source control programs, as do programs for wetland and riparian buffer restoration. -

Crepidula Fornicata

NOBANIS - Marine invasive species in Nordic waters - Fact Sheet Crepidula fornicata Author of this species fact sheet: Kathe R. Jensen, Zoological Museum, Natural History Museum of Denmark, Universiteteparken 15, 2100 København Ø, Denmark. Phone: +45 353-21083, E-mail: [email protected] Bibliographical reference – how to cite this fact sheet: Jensen, Kathe R. (2010): NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet – Crepidula fornicata – From: Identification key to marine invasive species in Nordic waters – NOBANIS www.nobanis.org, Date of access x/x/201x. Species description Species name Crepidula fornicata, Linnaeus, 1758 – Slipper limpet Synonyms Patella fornicata Linnaeus, 1758; Crepidula densata Conrad, 1871; Crepidula virginica Conrad, 1871; Crepidula maculata Rigacci, 1866; Crepidula mexicana Rigacci, 1866; Crepidula violacea Rigacci, 1866; Crepidula roseae Petuch, 1991; Crypta nautarum Mörch, 1877; Crepidula nautiloides auct. NON Lesson, 1834 (ISSG Database; Minchin, 2008). Common names Tøffelsnegl (DK, NO), Slipper limpet, American slipper limpet, Common slipper snail (UK, USA), Østerspest (NO), Ostronpest (SE), Amerikanische Pantoffelschnecke (DE), La crépidule (FR), Muiltje (NL), Seba (E). Identification Crepidula fornicata usually sit in stacks on a hard substrate, e.g., a shell of other molluscs, boulders or rocky outcroppings. Up to 13 animals have been reported in one stack, but usually 4-6 animals are seen in a stack. Individual shells are up to about 60 mm in length, cap-shaped, distinctly longer than wide. The “spire” is almost invisible, slightly skewed to the right posterior end of the shell. Shell height is highly variable. Inside the body whorl is a characteristic calcareous shell-plate (septum) behind which the visceral mass is protected. -

Kelp Cultivation Effectively Improves Water Quality and Regulates Phytoplankton Community in a Turbid, Highly Eutrophic Bay

Science of the Total Environment 707 (2020) 135561 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Kelp cultivation effectively improves water quality and regulates phytoplankton community in a turbid, highly eutrophic bay Zhibing Jiang a,b,d, Jingjing Liu a,ShangluLic,YueChena,PingDua,b,YuanliZhua,YiboLiaoa,d, Quanzhen Chen a, Lu Shou a, Xiaojun Yan e, Jiangning Zeng a,⁎, Jianfang Chen a,d a Key Laboratory of Marine Ecosystem and Biogeochemistry, State Oceanic Administration & Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Hangzhou, China b Function Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao, China c Marine Monitoring and Forecasting Center of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, China d State Key Laboratory of Satellite Ocean Environment Dynamics, Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, Hangzhou, China e Key Laboratory of Applied Marine Biotechnology, Ministry of Education, Marine College of Ningbo University, Ningbo, China HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • Kelp farming alleviated eutrophication and acidification. • Kelp farming greatly relieved light limi- tation and increased phytoplankton bio- mass. • Kelp farming appreciably enhanced phytoplankton diversity. • Kelp farming reduced the dominance of dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum. • Phytoplankton community differed sig- nificantly between the kelp farm and control area. article info abstract Article history: Coastal eutrophication and its associated harmful algal blooms have emerged as one of the most severe environ- Received 19 September 2019 mental problems worldwide. Seaweed cultivation has been widely encouraged to control eutrophication and Received in revised form 11 November 2019 algal blooms. Among them, cultivated kelp (Saccharina japonica) dominates primarily by production and area. -

The American Slipper Limpet Crepidula Fornicata (L.) in the Northern Wadden Sea 70 Years After Its Introduction

Helgol Mar Res (2003) 57:27–33 DOI 10.1007/s10152-002-0119-x ORIGINAL ARTICLE D. W. Thieltges · M. Strasser · K. Reise The American slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata (L.) in the northern Wadden Sea 70 years after its introduction Received: 14 December 2001 / Accepted: 15 August 2001 / Published online: 25 September 2002 © Springer-Verlag and AWI 2002 Abstract In 1934 the American slipper limpet 1997). In the centre of its European distributional range Crepidula fornicata (L.) was first recorded in the north- a population explosion has been observed on the Atlantic ern Wadden Sea in the Sylt-Rømø basin, presumably im- coast of France, southern England and the southern ported with Dutch oysters in the preceding years. The Netherlands. This is well documented (reviewed by present account is the first investigation of the Crepidula Blanchard 1997) and sparked a variety of studies on the population since its early spread on the former oyster ecological and economic impacts of Crepidula. The eco- beds was studied in 1948. A field survey in 2000 re- logical impacts of Crepidula are manifold, and include vealed the greatest abundance of Crepidula in the inter- the following: tidal/subtidal transition zone on mussel (Mytilus edulis) (1) Accumulation of pseudofaeces and of fine sediment beds. Here, average abundance and biomass was 141 m–2 through the filtration activity of Crepidula and indi- and 30 g organic dry weight per square metre, respec- viduals protruding in stacks into the water column. tively. On tidal flats with regular and extended periods of This was reported to cause changes in sediments and emersion as well as in the subtidal with swift currents in near-bottom currents (Ehrhold et al. -

Neoproterozoic Origin and Multiple Transitions to Macroscopic Growth in Green Seaweeds

Neoproterozoic origin and multiple transitions to macroscopic growth in green seaweeds Andrea Del Cortonaa,b,c,d,1, Christopher J. Jacksone, François Bucchinib,c, Michiel Van Belb,c, Sofie D’hondta, f g h i,j,k e Pavel Skaloud , Charles F. Delwiche , Andrew H. Knoll , John A. Raven , Heroen Verbruggen , Klaas Vandepoeleb,c,d,1,2, Olivier De Clercka,1,2, and Frederik Leliaerta,l,1,2 aDepartment of Biology, Phycology Research Group, Ghent University, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; bDepartment of Plant Biotechnology and Bioinformatics, Ghent University, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; cVlaams Instituut voor Biotechnologie Center for Plant Systems Biology, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; dBioinformatics Institute Ghent, Ghent University, 9052 Zwijnaarde, Belgium; eSchool of Biosciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia; fDepartment of Botany, Faculty of Science, Charles University, CZ-12800 Prague 2, Czech Republic; gDepartment of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742; hDepartment of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; iDivision of Plant Sciences, University of Dundee at the James Hutton Institute, Dundee DD2 5DA, United Kingdom; jSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Western Australia, WA 6009, Australia; kClimate Change Cluster, University of Technology, Ultimo, NSW 2006, Australia; and lMeise Botanic Garden, 1860 Meise, Belgium Edited by Pamela S. Soltis, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, and approved December 13, 2019 (received for review June 11, 2019) The Neoproterozoic Era records the transition from a largely clear interpretation of how many times and when green seaweeds bacterial to a predominantly eukaryotic phototrophic world, creat- emerged from unicellular ancestors (8). ing the foundation for the complex benthic ecosystems that have There is general consensus that an early split in the evolution sustained Metazoa from the Ediacaran Period onward. -

Edible Seaweed from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Edible seaweed From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Edible seaweed are algae that can be eaten and used in the preparation of food. They typically contain high amounts of fiber.[1] They may belong to one of several groups of multicellular algae: the red algae, green algae, and brown algae. Seaweeds are also harvested or cultivated for the extraction of alginate, agar and carrageenan, gelatinous substances collectively known as hydrocolloids or phycocolloids. Hydrocolloids have attained commercial significance, especially in food production as food A dish of pickled spicy seaweed additives.[2] The food industry exploits the gelling, water-retention, emulsifying and other physical properties of these hydrocolloids. Most edible seaweeds are marine algae whereas most freshwater algae are toxic. Some marine algae contain acids that irritate the digestion canal, while some others can have a laxative and electrolyte-balancing effect.[3] The dish often served in western Chinese restaurants as 'Crispy Seaweed' is not seaweed but cabbage that has been dried and then fried.[4] Contents 1 Distribution 2 Nutrition and uses 3 Common edible seaweeds 3.1 Red algae (Rhodophyta) 3.2 Green algae 3.3 Brown algae (Phaeophyceae) 3.3.1 Kelp (Laminariales) 3.3.2 Fucales 3.3.3 Ectocarpales 4 See also 5 References 6 External links Distribution Seaweeds are used extensively as food in coastal cuisines around the world. Seaweed has been a part of diets in China, Japan, and Korea since prehistoric times.[5] Seaweed is also consumed in many traditional European societies, in Iceland and western Norway, the Atlantic coast of France, northern and western Ireland, Wales and some coastal parts of South West England,[6] as well as Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. -

Snails, Limpets and Chitons: Moving on Edited by Holly Anne Foley and Karen Mattick Marine Science Center, Poulsbo, Washington

TEACHER BACKGROUND Unit 3 - Tides and the Rocky Shore Snails, Limpets and Chitons: Moving On Edited by Holly Anne Foley and Karen Mattick Marine Science Center, Poulsbo, Washington Key Concepts 1. Snails, limpets and chitons each crawl on rocks with a muscular foot to find food and more favorable conditions. 2. These mobile animals also adhere tightly to rocks to survive low tide and to deter predators. Background Some of the most common animals in rocky shore habitats are the snails, limpets and chitons. Unlike barnacles, these animals are mobile. They each have a muscular foot that moves in contractions which appear as waves. The wave movement propels the animal forward a minute step at a time. The wave of contraction push-pulls the animal along. The slime trail snails, limpets and chitons leave has unique chemical properties that alternately act as a glue then as a lubricant depending on the pressure placed on the slime by the animal. The stationary portion is held in place by the glue as the moving portion is easily moved over the lubricated surface. Materials For each student or pair of students: • 1 snail, limpet or chiton • 1 glass jar with a lid • sea water • washable felt marker such as an overhead transparency pen • 30 cm or so string • millimeter ruler • “Snails, Limpets and Chitons: Moving On” student pages Teaching Hints “Snails, Limpets and Chitons: Moving On” gives your students a chance to observe movement in a living marine gastropod or the similar chitons. You can readily obtain periwinkles (Littorina species) or other snails, limpets or chitons from the intertidal zone or from biological supply houses. -

Kelp Aquaculture

Aquaculture in Shared Waters Kelp Aquaculture Sarah Redmond1 ; Samuel Belknap2 ; Rebecca Clark Uchenna3 “Kelp” are large brown marine macroalgae species native to New England and traditionally wild harvested for food. There are three commercially important kelp species in Maine—sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima), winged kelp (Alaria esculenta), and horsetail kelp (Laminaria digitata). Maine is developing techniques for culturing kelp on sea farms as a way for fishermen and farmers to diversify their operations while providing a unique, high quality, nutritious vegetable seafood for new and existing markets. Kelp is grown on submerged horizontal long lines on leased sea farms from September to May, making it a “winter crop” for Maine. The simple farm design, winter season, and relatively low startup costs allow for new and existing sea farmers to experiment with this newly developing type of aquaculture on Maine’s coast. “Kelp” can refer to sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima), Alaria (Alaria esculenta), or horsetail kelp (Laminaria digitata). Sugar kelp has been cultivated in Maine for several years, and successful experimental cultivation has been done with species such as Alaria. These photos are examples of the cultivation stages of sugar kelp. Microscopic Seeded kelp line Kelp line at time of kelp seed harvest 1 Sarah Redmond • Marine Extension Associate, Maine Sea Grant College Program and University of Maine Cooperative Extension 33 Salmon Farm Road Franklin, ME • 207.422.6289 • [email protected] 2 Samuel Belknap • University of Maine • 234C South Stevens Hall Orono, ME • 207.992.7726 • [email protected] 3 Rebecca Clark Uchenna • Island Institute • Rockland, ME • 207.691.2505 • [email protected] Is there a viable market for Q: kelps grown in Maine? aine is home to a handful of consumers are looking for healthier industry, the existing producers and Mcompanies that harvest sea alternatives. -

Pierce County Nearshore Species List Compiled from the Pt

Pierce County Nearshore Species List Compiled from the Pt. Defiance Park Bioblitz 2011 ID COMMON NAME √ ID COMMON NAME √ 31 Acorn barnacle X 34 Hermit crab sp. X 43 Aggregate green anemone X 35 Isopod sp. X 30 Amphipod sp. X 36 Jellyfish sp. X 95 Anemone sp. 73 Large leaf worm X 60 Barnacle nudibranch X 12 Leafy hornmouth X 48 Barnacle sp. X 74 Leather limpet 68 Bent-nose macoma 13 Leather star X 69 Black and white brittle star 14 Lewis's moonsnail X 92 Black turban X 37 Limpet sp. 63 Blood star X 75 Lined chiton X 56 Butter clam X 76 Lined ribbon worm 65 Calcareous tube worm X 108 Mask limpet X 103 California mussel X 67 Moon jellyfish X 1 California sea cucumber 32 Mossy chiton X 53 Checkered periwinkle X 61 Mottled star X 32 Chiton sp. 38 Mussel sp. X 33 Clam sp. X 77 Northern feather duster w X 70 Coonstripe shrimp 15 Northern kelp crab 59 Crab sp. X 39 Nudibranch sp. X 96 Dog welk sp. X 78 Nuttall's cockle 93 Dogwinkle sp. X 62 Ochre star X 3 Dungeness crab X 16 Opalescent (aeolid) nudib X 57 Eccentric sand dollar X 17 Orange sea cucumber X 112 Fat gaper X 18 Orange sea pen 4 Feathery shipworm X 19 Oregon triton 5 Fish-eating anemone 40 Oyster sp. 101 Flat porcelain crab 79 Pacific blue mussel X 6 Fringed tube worm 110 Pacific gaper 8 Giant (nudibranch) dendronotid 99 Pacific geoduck clam X 7 Giant barnacle X 80 Pacific oyster 9 Giant pacific octopus 97 Periwinkle sp. -

NIEA ID Guide Crepidula Fornicata Slipper Limpet

Scan for more Slipper Limpet information Species Description Scientific name: Crepidula fornicata AKA: American Slipper Limpet, Common American slippersnail Native to: North-east US Habitat: Wide range of habitats particularly in wave- protected bays, estuaries or sheltered sides of wave- This species has an oval shell, up to 5 cm in length, with a much reduced spire. The large aperture has a shelf, or septum, extending half its length. The shell is smooth with irregular growth lines and white, cream, yellow or pinkish in colour with streaks or blotches of red or brown. Slipper limpets are commonly found in curved chains of up to 12 animals. Large shells are found at the bottom of the chain, with the shells becoming progressively smaller towards the top. Crepidula fornicata is present in Northern Ireland in Belfast Lough and other coastal sites. Other records exist from around Ireland over the last century however, none of these sites are currently thought to be supporting a population. Crepidula fornicata most likely arrived in Ireland with consignments of mussels. Other possible pathways include; with consignments of oysters, on drifting materials or due to dispersal of larvae. Slipper limpet competes with, and can displace, other filter-feeding invertebrates. The species can be a serious pest of oyster and mussel beds. Slipper limpet is listed under Schedule 9 of The Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order 1985 and as such, it is an offence to release or allow this species to escape into the wild. Key ID Features Tapered point set to one -

Associated Heterotrophic Protists, Stereomyxa Ramosa, Nitzschia Alba and Labyrinthula Sp

AQUATIC MICROBIAL ECOLOGY Vol. 21: 49-57,2000 Published February 21 Aquat Microb Ecol Utilisation of seaweed carbon by three surface- associated heterotrophic protists, Stereomyxa ramosa, Nitzschia alba and Labyrinthula sp. Evelyn ~rmstrong'~~~*,Andrew ~ogerson~,John W. ~eftley~ 'University Marine Biological Station Millport, Isle of Curnbrae KA28 OEG, Scotland, UK 'Oceanographic Center, Nova Southeastern University, 8000 N. Ocean Drive, Dania Beach, Florida 33004, USA 'Scottish Association for Marine Science, Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory. PO Box 3, Oban. Argyll PA34 4AD. Scotland, UK ABSTRACT: In view of the abundance of protists associated with seaweeds and the diversity of nutri- tional strategies displayed by protists in general, the ability of 3 closely associated protists to utilise sea- weed carbon was investigated. Stereomyxa ramosa, Nitzschja alba and Labyrinthula sp. were cultured with seaweed polysaccharides as well as seaweed itself. N. alba and Labyrinthula sp. were found to utilise seaweed polysaccharides in axenic culture. All 3 protists were capable of penetrating intact but 'damaged' (autoclaved) seaweed particularly when bacteria were present. The possibility that these and other heterotrophic protists are directly removing macroalgal carbon in the field is discussed. KEY WORDS: Protist . Heterotroph - Seaweed. Carbon . Utilisation INTRODUCTION (Lucas et al. 1981, Rieper-Kirchner 1989).This conver- sion of dissolved carbon into particulate forms (as bac- Heterotrophic protists are abundant on seaweed sur- terial biomass) is thought to be a major link to higher faces (Rogerson 1991, Armstrong et al. 2000) because trophic levels (Newell et al. 1980). To compete effec- seaweeds are rich in bacterial prey (Laycock 1974, tively with bacteria, heterotrophic protists would need Shiba & Taga 1980). -

Population Characteristics of the Limpet Patella Caerulea (Linnaeus, 1758) in Eastern Mediterranean (Central Greece)

water Article Population Characteristics of the Limpet Patella caerulea (Linnaeus, 1758) in Eastern Mediterranean (Central Greece) Dimitris Vafidis, Irini Drosou, Kostantina Dimitriou and Dimitris Klaoudatos * Department of Ichthyology and Aquatic Environment, School of Agriculture Sciences, University of Thessaly, 38446 Volos, Greece; dvafi[email protected] (D.V.); [email protected] (I.D.); [email protected] (K.D.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 February 2020; Accepted: 19 April 2020; Published: 21 April 2020 Abstract: Limpets are pivotal for structuring and regulating the ecological balance of littoral communities and are widely collected for human consumption and as fishing bait. Limpets of the species Patella caerulea were collected between April 2016 and April 2017 from two sites, and two samplings per each site with varying degree of exposure to wave action and anthropogenic pressure, in Eastern Mediterranean (Pagasitikos Gulf, Central Greece). This study addresses a knowledge gap on population characteristics of P. caerulea populations in Eastern Mediterranean, assesses population structure, allometric relationships, and reproductive status. Morphometric characteristics exhibited spatio-temporal variation. Population density was significantly higher at the exposed site. Spatial relationship between members of the population exhibited clumped pattern of dispersion during spring. Broadcast spawning of the population occurred during summer. Seven dominant age groups were identified, with the dominant cohort in the third-year