Neolithic & Early Bronze Age Berkshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Houses 7 Apartments Sl4

SL4 6PE 5 HOUSES 7 APARTMENTS An impressive collection of five contemporary houses and seven spectacular two bedroom apartments set within a prestigious gated development in the Berkshire village of Eton WWW.GABLES-ETON.COM 2 1 five incredible houses and seven spectacular apartments ThE GABlEs is A prEsTiGious dEvElopmEnT comprisinG fivE spAcious And The development is located close to the highly desirable Offering the perfect combination of contemporary living village of Eton, recently acclaimed as one of the ten most and period charm, in a delightful and extremely convenient conTEmporAry housEs sET in ThE Grounds of A sTunninG vicToriAn beautiful villages in England.* Formerly owned by the setting within easy reach of both London and Heathrow, a BuildinG. ThE BuildinG iTsElf hAs undErGonE A sympAThETic rEnovATion world-famous public school, Eton College, the historically home at The Gables gives you the very best of all worlds. significant building dates from 1843 and features an To crEATE sEvEn luxury Two BEdroom ApArTmEnTs. impressive front façade with Dutch gables and distinctive diamond diaper patterns in red brick. *Source: The Travel Pages 2 3 COMPUTER GENERATED IMAGE FOR ILLUSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY A perfect blend of period elegance and contemporary style All homEs AT ThE GABlEs ArE finishEd To ExAcTinG sTAndArds. cArEful As you would expect of a development of this calibre, Conveniently located on the fringes of the affluent security is taken very seriously and all homes in the gated village of Eton, less than an hour from London, a home ThouGhT hAs BEEn GivEn To ThE dETAilinG of ThEsE GrAcious rEsidEncEs community feature video entry systems, high security locks at The Gables is the perfect place for you to call home. -

Blewbury Neighbourhood Development Plan Housing Needs Survey: Free-Form Comments This Is a Summary of Open-Ended Comments Made in Response to Questions in the Survey

! !"#$%&'()*#+,-%.&'-../) 0#1#".23#45)6"74) 89:;)<)89=:) "##$%&'($)! %"#$%&'(4#+,-%.&'-../2"74>.',) :;)?2'+")89:;) ! @.45#45A) "##$%&'*!"+!,-.'%./$0!1$2$-!34$-5672)!.%&!8-79%&2.:$-!;677&'%/!'%!<6$2=9->! "##$%&'*!<+!?79)'%/!@$$&)!19-4$>! "##$%&'*!A+!B.%&)(.#$!AC.-.(:$-!"))$))D$%:! "##$%&'*!,+!E'66./$!AC.-.(:$-!"))$))D$%:! ! ! ! ! ! !""#$%&'(!)()!"#$%#&'()*'+'"),-'"./0+1)#%2)3"04%2+#5'"! !"##$%&'(%&()"*+,-./) ! ! ! ! "#$%!&'()!$%!$*+)*+$,*'--.!-)/+!0-'*1! ! !""#$%&'(!!"!!"#$%#&'()*'+'"),-'"./0+1)#%2)3"04%2+#5'"! !"##$%&'(%&()"*+,-./! !"#$%&'($)**+$ !"#$%&%"'#(%)$*+#,)$'*#-.#/0%123$(#4)5%#*3..%$%6#*%1%$#-5%$.0-1*#)"6#7$-3"61)'%$#.0--68"7# 63$8"7# ,%$8-6*# -.# 1%'# 1%)'4%$9# :4%$%# 8*# &-"&%$"# '4)'# .3$'4%$# 4-3*8"7# 6%5%0-,;%"'# 8"# '4%# 5800)7%#&-306#%<)&%$2)'%#'4%#,$-20%;9#!"#'48*#),,%"68<#1%#%<,0-$%#14(#*3&4#,$-20%;*#-&&3$# )"6# &-"*86%$# '4%# ,0)""8"7# ,-08&(# 7386)"&%# '4)'# ;874'# 2%# "%%6%6# 8"# '4%# /0%123$(# =%8742-3$4--6#>%5%0-,;%"'#?0)"#'-#%"*3$%#'4%#*8'3)'8-"#6-%*#"-'#1-$*%"9# @%1%$# -5%$.0-1# -&&3$*# 14%"# $)1+# 3"'$%)'%6# *%1)7%# A1)*'%1)'%$B# 2$8;*# -5%$# .$-;# '4%# ;)"4-0%*#)"6#73008%*#-.#'4%#*%1%$)7%#"%'1-$C#'-#.0--6#0)"6+#7)$6%"*+#$-)6*+#,)'4*#)"6+#8"#'4%# 1-$*'#&)*%*+#,%-,0%D*#4-3*%*9#@3&4#3"'$%)'%6#*%1)7%#8*#"-'#-"0(#3",0%)*)"'#'-#*%%#)"6#*;%00# 23'#8'#)0*-#&)"#,-*%#)#'4$%)'#'-#43;)"#4%)0'4#)"6#'4%#%"58$-";%"'9## E5%$.0-1*# -&&3$# ;-*'# &-;;-"0(# 63$8"7# 4%)5(# $)8".)00# A*'-$;B# %5%"'*# -$# ).'%$# ,%$8-6*# -.# ,$-0-"7%6# $)8".)009# :4%(# )$%# 3*3)00(# &)3*%6# 2(# 0)$7%# 5-03;%*# -.# *3$.)&%# 1)'%$# -$# 7$-3"61)'%$# -

Eton Community Association

Dear Sir/Madam, At a recent meeting of representatives from Eton Community Association, we talked about commenting on the proposed Ward Boundaries as they affect Eton Town Council, which includes the current wards of Eton and Castle, and Eton Wick. Option D is of significant concern. This is not aligned with the Eton Community nor indeed the Eton & Eton Wick Neighbourhood Plan, which is currently out for consultation with the submission version (Regulation 16). We are aware that the Eton & Eton Wick Town Council is opposed to option D too. These are reasons that give cause for concern: 1 The proposal seems to be based on only one of the 3 criteria to be considered, namely numbers of voters. The criteria of relevance to the community seens to have been disregarded. 2 Eton with Eton Wick is a self-contained community with absolutely no relationship with Datchet and Horton. 3 The community has just completed a Neighbourhood Plan for Eton and Eton Wick combined, and a huge amount of time, hard work and money will go to waste by attaching two new whole communities to it. Having attended the adjoining Neighbourhood Plan local consultations, my colleagues and I have good knowledge of various NPs, including Windsor 2030, Outer Windsor, Horton & Wraysbury. It is clear that our alignment with and inter-relationship with Windsor is strong. We have no such relationship with Wraysbury or Datchet. 4 Our two existing Ward Councillors have worked tirelessly for Eton and Eton Wick, each being responsible for one of the Wards. This system has served the community well and to change into a multi-dimensional system with several councillors looking after a conglomerate of diverse communities gives cause for concern. -

6 September 2019

Planning Applications Decided Week Ending - 6 September 2019 The applications listed below have been DECIDED by the Council. Ward: Parish: Appn. Date: 8th August 2019 Appn No.: 19/30021 Type: Spheres of Mutual Interest Proposal: Extension to existing ferry landing and formation of seating area through bank excavation along with the provision of a berth pile 2.5m above water level. Location: Existing Jetty Adjacent To Runnymede Boathouse Windsor Road Egham Applicant: Ruth Menezes Decision Type: Delegated Decision: No Objection Date of Decision: 3 September 2019 HYM Ward: Ascot & Sunninghill Parish: Sunninghill And Ascot Parish Appn. Date: 29th May 2019 Appn No.: 19/01425 Type: Full Proposal: Single storey rear extension (retrospective). Location: Woodpeckers 13 Woodlands Close Ascot SL5 9HU Applicant: Mr And Mrs James c/o Agent: Mr Nigel Bush NHB Architectural Services Ltd St Marys House Point Mills Bissoe Truro TR4 8QZ Decision Type: Delegated Decision: Application Permitted Date of Decision: 4 September 2019 JS Ward: Ascot & Sunninghill Parish: Sunninghill And Ascot Parish Appn. Date: 18th June 2019 Appn No.: 19/01625 Type: Full Proposal: Change of use of the first floor from Class C3 (dwellinghouses) to Class B1 (offices) with side dormers and second floor roof terrace. Location: Annexe Kingswick House Kingswick Drive Ascot SL5 7BH Applicant: Mr Ewan Boyd c/o Agent: Mr Ewan Boyd Walker Graham Architects 44 Horton View Banbury OX16 9HP Decision Type: Delegated Decision: Application Withdrawn Date of Decision: 4 September 2019 JR Ward: Ascot & Sunninghill Parish: Sunninghill And Ascot Parish Appn. Date: 9th July 2019 Appn No.: 19/01774 Type: Cert of Lawfulness of Proposed Dev Proposal: Certificate of lawfulness to determine whether the proposed garage conversion is lawful. -

Historic Landscape Character Areas and Their Special Qualities and Features of Significance

Historic Landscape Character Areas and their special qualities and features of significance Volume 1 Third Edition March 2016 Wyvern Heritage and Landscape Consultancy Emma Rouse, Wyvern Heritage and Landscape Consultancy www.wyvernheritage.co.uk – [email protected] – 01747 870810 March 2016 – Third Edition Summary The North Wessex Downs AONB is one of the most attractive and fascinating landscapes of England and Wales. Its beauty is the result of many centuries of human influence on the countryside and the daily interaction of people with nature. The history of these outstanding landscapes is fundamental to its present‐day appearance and to the importance which society accords it. If these essential qualities are to be retained in the future, as the countryside continues to evolve, it is vital that the heritage of the AONB is understood and valued by those charged with its care and management, and is enjoyed and celebrated by local communities. The North Wessex Downs is an ancient landscape. The archaeology is immensely rich, with many of its monuments ranking among the most impressive in Europe. However, the past is etched in every facet of the landscape – in the fields and woods, tracks and lanes, villages and hamlets – and plays a major part in defining its present‐day character. Despite the importance of individual archaeological and historic sites, the complex story of the North Wessex Downs cannot be fully appreciated without a complementary awareness of the character of the wider historic landscape, its time depth and settlement evolution. This wider character can be broken down into its constituent parts. -

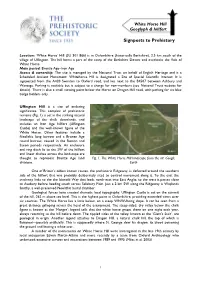

Signposts to Prehistory

White Horse Hill Geoglyph & hillfort Signposts to Prehistory Location: ‘White Horse’ Hill (SU 301 866) is in Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), 2.5 km south of the village of Uffington. The hill forms a part of the scarp of the Berkshire Downs and overlooks the Vale of White Horse. Main period: Bronze Age–Iron Age Access & ownership: The site is managed by the National Trust on behalf of English Heritage and is a Scheduled Ancient Monument. Whitehorse Hill is designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest. It is signposted from the A420 Swindon to Oxford road, and lies next to the B4507 between Ashbury and Wantage. Parking is available but is subject to a charge for non-members (see National Trust website for details). There is also a small viewing point below the Horse on Dragon Hill road, with parking for six blue badge holders only. Uffington Hill is a site of enduring significance. This complex of prehistoric remains (Fig. 1) is set in the striking natural landscape of the chalk downlands, and includes an Iron Age hillfort (Uffington Castle) and the well-known figure of the White Horse. Other features include a Neolithic long barrow and a Bronze Age round barrow, reused in the Roman and Saxon periods respectively. An enclosure and ring ditch lie to the SW of the hillfort and linear ditches across the landscape are thought to represent Bronze Age land Fig. 1. The White Horse Hill landscape from the air. Google divisions. Earth One of Britain’s oldest known routes, the prehistoric Ridgeway, is deflected around the southern side of the hillfort that was probably deliberately sited to control movement along it. -

Royal Borough of Windsor & Maidenhead Bus Stop Accessibility

Royal Borough of Windsor & Maidenhead Bus Stop Accessibility Programme 2016-2017 Background • RBWM is undertaking a program of works to improve accessibility at bus stops. This includes the provision of raised kerbs and level access. • Works have been undertaken at bus stops which do not meet the required minimum kerb height of 125mm. • In the majority of cases, the pavement adjacent to the raised kerb has been resurfaced, to provide a smooth surface and level access from kerb to bus. • The program initially focused on bus stops within Windsor and Maidenhead town centres. It has subsequently been expanded on a rolling basis, by bus route. Works to date Route Route Description Program Area Route 5 Farmers Way - Maidenhead Town Centre - Full Route Cranbrook Drive Courtney Buses Route 7 Maidenhead Town Centre - Cox Green - Woodlands Full Route Park Courtney Buses Route 8 Boulters Lock - Maidenhead Town Centre - Halifax Full Route Road Courtney Buses Routes 16 & 16A Maidenhead to Windsor via Bray, Holyport, Fifield Full Route (route 16A) and Dedworth Courtney Buses Route 60 Eton Wick - Slough - Datchet - Heathrow Terminal 5 Eton Wick, Eton, Datchet & Wraysbury First Berkshire Route 71 Slough - Windsor - Staines - Heathrow Terminal 5 Windsor & Old Windsor First Berkshire Route 77 Heathrow Terminal 5 - Slough - Windsor - Dedworth Clewer, Dedworth & Windsor First Berkshire Route 702 Bracknell - Windsor - Slough - London Windsor & Clewer. Including Winkfield Road Greenline Market Street, Maidenhead Maidenhead Library Lambourne Drive, opp, Cox Green Lambourne drive, adj, Cox Green. -

15 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

15 bus time schedule & line map 15 Slough Town Centre - Maidenhead Town Centre View In Website Mode The 15 bus line (Slough Town Centre - Maidenhead Town Centre) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Eton Wick: 7:05 AM - 6:15 PM (2) Maidenhead Town Centre: 9:05 AM - 3:55 PM (3) Slough Town Centre: 7:26 AM - 6:38 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 15 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 15 bus arriving. Direction: Eton Wick 15 bus Time Schedule 14 stops Eton Wick Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:05 AM - 6:15 PM Slough Bus Station, Slough Town Centre Tuesday 7:05 AM - 6:15 PM Landmark Place, Slough Town Centre Windsor Road, Slough Wednesday 7:05 AM - 6:15 PM Albert Street, Chalvey Thursday 7:05 AM - 6:15 PM Friday 7:05 AM - 6:15 PM Windsor Road Mcdonalds, Chalvey A332, Windsor Saturday 7:05 AM - 6:15 PM Pococks Lane, Eton Eton College, Eton 15 bus Info Brocas Street, Eton Direction: Eton Wick Brocas Street, Windsor Stops: 14 Trip Duration: 20 min Keats Lane, Eton Line Summary: Slough Bus Station, Slough Town Centre, Landmark Place, Slough Town Centre, Albert Broken Furlong, Eton Street, Chalvey, Windsor Road Mcdonalds, Chalvey, Pococks Lane, Eton, Eton College, Eton, Brocas Bunces Close, Eton Wick Street, Eton, Keats Lane, Eton, Broken Furlong, Eton, Bunces Close, Eton Wick, The Walk, Eton Wick, The Walk, Eton Wick Moores Lane, Eton Wick, Tilstone Avenue, Eton Wick, Colenorton Crescent, Eton Wick Moores Lane, Eton Wick Tilstone Avenue, Eton Wick Colenorton -

White Horse Hill to Ashdown

Galloping across the Downs – 7 ½ miles White Horse Hill to AshdownNT Properties nearby: Buscot and Coleshill Estates, Great Coxwell Barn, Buscot Park Enjoy a walk across the ancient chalk downs of Oxfordshire and absorb the history found along this enigmatic stretch of the ancient Ridgeway. Encompassing Neolithic history to WWII inhabitants, this is a walk that will leave the 21st Century In summer, many behind for a few hours. butterfly species can be seen along the route. Look out for the Map & grid ref: OS Landranger 174, Explorer 170 SU293866 Chalkhill Blue, found Getting there: around Uffington Buses: 47, 47a, X47– all limited service on Sat, Swindon - Uffington, weekday service Castle and other to Ashdown, alight at Rose and Crown. Go to www.swindonbus.info for further details. sunny south- facing Road: Car parks at White Horse Hill, off the B4507 and Ashdown Estate on the B4000 spots. (SU 285823) © NT/ Caroline Searle Cycling: The Ridgeway National off-road Cycle Route criss-crosses the walk Facilities: Nearby pubs in Woolstone, Uffington and Ashbury. From the top of the Points of interest: Hill, by the Horse’s head, look out into t The White Horse and Uffington Castle: The oldest dated chalk figure in England is the vale of the White about 3000 years old whilst the Castle is about 2500 years old. During the 18th and 19th Horse. On a clear centuries the castle would have held a ‘Pastime’ every 7 years to clean the horse. day you can see over 35 miles away t Wayland’s Smithy: A Neolithic burial long barrow steeped in history and legend. -

The Cotswolds Berkshire Downs North Wessex Downs

THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 River Evenlode River Glyme River Cherwell The Cotswolds River Ray River Windrush River Churn Eynsham River Leach " River Thame River Coln " OXFORD Chilterns FAIRFORD " CIRENCESTER " River Chess " LECHLADE e ABINGDON" River Misbourn " DORCHESTER " River Ock R River Wye CRICKLADE i v e r e T River Lea or Le h a m e s River Ray WALLINGFORD Marlow " Cookham " Colne Brook Henley-on-Thames " MAIDENHEAD LONDON " " " Goring mes Berkshire Downs ETON Tha " r River Lambourn e v " i R WINDSOR " River Pang READING " STAINES River Kennet " KINGSTON UPON THAMES " River Loddon CHERTSEY River Mole River Hart Blackwater River North Wessex Downs North Downs Guildford " River Wey 0 20 km Figure 1: The Thames Valley and surrounding region showing topography, rivers and main historic settlements (map courtesy of the British Geological Survey) THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 Figure 2: 14th-century watermill and eel trap from the Luttrell Psalter (©British Library) THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 Figure 3: The London Stone, Staines, Surrey (©Historic England) THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 Figure 4: Abbey Mills, Chertsey, Surrey, c 1870 (©Historic England) THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 Figure 5: Artist’s impression of Blackfriars ship 3 (after Marsden 1996, 88, fig. -

Cedar Cottage, 27 Alma Road, Eton Wick, Windsor, Berkshire, SL4 6JZ Guide Price £440,000 Freehold

Windsor Office: T: 01753 833000 E: [email protected] Cedar Cottage, 27 Alma Road, Eton Wick, Windsor, Berkshire, SL4 6JZ Guide Price £440,000 Freehold 3 Bedrooms 2 Bathrooms Off street parking Detached Courtyard garden EPC -F Description An absolutely charming detached, Victorian 3 bedroom cottage in one of the most desirable parts of this popular village. The house is well proportioned and has many period features including beautiful Victorian fireplaces, decorative glass and original floor boards combined with updated modern bathrooms and kitchen. Entrance Open brick arch entrance porch leads with period half glazed wooden door to entrance hallway. Dining Room Window overlooking the garden and open arch to the kitchen. Exposed floor boards and Victorian fireplace with decorative tile inserts. Integral storage cupboards. Overhead light point. Wall mounted double radiator. Living Room Bay -fronted to the front. Feature Victorian fireplace with decorative tile inserts. 2 wall lights and 1 overhead light point. Wall mounted radiator. Kitchen A large dual aspect kitchen with an extensive range of floor and wall mounted timber units comprising cupboards, drawers and display units with granite effect worktops over. There is an integrated oven with 4 burner hob over and inset stainless steel sink unit with mixer tap. Tiled splashbacks and recessed ceiling lights. Walk in pantry. Space and plumbing for washing machine. Side door to garden area. Ground floor shower room Glass shower enclosure with inset shower unit, corner wall mounted wash hand basin and low level wc. Tiled walls and floor. Window to side with opaque glass and wall mounted light point. -

Countryman Pages

june 2015 9 ngland’s thirty-three Areas of Out - has left us some fascinating treasures, Exploring the Estanding Natural Beauty (AONB) including the beautiful Uffington have been described as the “jewels of the White Horse, the magical Wayland’s English landscape”, and the North Wes - Smithy and several Iron Age hill forts. North Wessex Downs sex Downs, the third largest of these The AONB then sweeps south, fol - AONBs, is no exception. lowing the River Thames to Pang - Designated in 1972, the North Wes - bourne before encircling Newbury Steve Davison is in chalk country as he celebrates sex Downs encompasses 668 square and part of the Kennet Valley, to the region’s history and heritage miles of rolling chalk landscape, encompass the northern reaches of the stretching from its western tip near North Hampshire Downs. The south - Calne in Wiltshire across a broad arc ern edge stretches westwards, passing to the south of Swindon, passing north of Andover to take in the Vale of through Oxfordshire and Berkshire, Pewsey, and the market towns of with a steep scarp slope looking out Hungerford and Marlborough. over the Vale of White Horse, to meet The predominant feature is the the River Thames on its eastern edge, underlying Cretaceous (99-65 million adjoining the Chilterns across the years ago) chalk geology; the North Goring Gap. Wessex Downs cover one of the most Along the crest of the downs, fol - continuous tracts of chalk downland lowed for much of the way by the in England. The chalk itself is formed Ridgeway — probably the oldest green from the remains of billions of minute road in England — prehistoric man sea creatures (known as coccoliths) The rolling contours of the chalk downs overlooking the Vale of Pewsey.