Status of Muslim Youth in Bihar Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of India 100935 Parampara Foundation Hanumant Nagar ,Ward No

AO AO Name Address Block District Mobile Email Code Number 97634 Chandra Rekha Shivpuri Shiv Mandir Road Ward No 09 Araria Araria 9661056042 [email protected] Development Foundation Araria Araria 97500 Divya Dristi Bharat Divya Dristi Bharat Chitragupt Araria Araria 9304004533 [email protected] Nagar,Ward No-21,Near Subhash Stadium,Araria 854311 Bihar Araria 100340 Maxwell Computer Centre Hanumant Nagar, Ward No 15, Ashram Araria Araria 9934606071 [email protected] Road Araria 98667 National Harmony Work & Hanumant Nagar, Ward No.-15, Po+Ps- Araria Araria 9973299101 [email protected] Welfare Development Araria, Bihar Araria Organisation Of India 100935 Parampara Foundation Hanumant Nagar ,Ward No. 16,Near Araria Araria 7644088124 [email protected] Durga Mandir Araria 97613 Sarthak Foundation C/O - Taranand Mishra , Shivpuri Ward Araria Araria 8757872102 [email protected] No. 09 P.O + P.S - Araria Araria 98590 Vivekanand Institute Of 1st Floor Milan Market Infront Of Canara Araria Araria 9955312121 [email protected] Information Technology Bank Near Adb Chowk Bus Stand Road Araria Araria 100610 Ambedkar Seva Sansthan, Joyprakashnagar Wardno-7 Shivpuri Araria Araria 8863024705 [email protected] C/O-Krishnamaya Institute Joyprakash Nagar Ward No -7 Araria Of Higher Education 99468 Prerna Society Of Khajuri Bazar Araria Bharga Araria 7835050423 [email protected] Technical Education And ma Research 100101 Youth Forum Forbesganj Bharga Araria 7764868759 [email protected] -

Download (814.04

National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of Higher Education, Government of India Farogh-e-Urdu Bhawan, FC-33/9, Institutional Area Jasola, New Delhi-110 025 SANCTION ORDER Consequent upon the recommendations of the Grant-In-Aid Committee in its meeting held on 5thMarch, 2017 sanction is accorded to the Grant-in-Aid of Rs. 1,93,50,403/- (Rs. One Crore Ninety Three Lakhs Fifty Thousand Four Hundred Three only) in favour of the following NGOs/ Organizations/Authors/Submitters (amount is indicated against each one), for undertaking selection of Urdu Promotional activities. Proposals for Seminar/Conference/Workshop/Mushaira S. S. Name & Address of the NGO/VO/ Topic Sanctioned Grant No No Institutions (in Rs.) Andhra Pradesh 1. 1. Dr. Mohd. Nisar Ahamed National Level 1,00,000/- Asstt. Prof. Seminar Dept. of Arabic, Persian & Urdu Junoobi Hind mein Urdu Nazm Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati- 1960 ke Baad خٌْثی ہٌذ هیں اسدّ ًظن 1960 کے ثعذ AP ,517501 9441393561 [email protected] 2. 2. Dr. Irfana Begum National Level 1,00,000/- Asstt. Prof. Seminar Dept. of Urdu Ekkiswein Sadi mein Urdu K.V.R. Govt. College Women Afsana اکیغْیں صذی هیں اسدّ افغبًہ ,(Autonomous) Kurnool-518004, AP 9966458939 [email protected] 3. 3. Dr. S. A. Sattar Saheb National Level 1,00,000/- Prof. & Registrar Seminar Dept. of Urdu Urdu Ghazal: Kal Aaj aur Kal اسدّ غضل: کل آج اّس کل ,Dr. Abdul Haq Urdu University Kurnool-518001, AP 9440167176 [email protected] 4. 4. Mr. Usman Anjum National Level 1,50,000/- President Seminar/Mushaira Bazm-e-Asnaam Ekkiswein Sadi mein Urdu Literary & Cultural Association Tanqeed ki Peshraft اکیغْیں صذی هیں اسدّ تٌمیذ کی پیF-204, Sania Homes, Laxmi Nagar ؼ سفت ,Colony, Sujata Nagar Visakhapatnam-530051, A.P 9393125906 [email protected] 4,50,000/- Bihar 5. -

Final Report- Community Participation of Embankment Surveillance

Volume-I FINAL REPORT Submitted to: Joint Director, Flood Management Improvement Support Centre Water Resources Department 2nd Floor, Jal Sansadhan Bhawan Anisabad, Patna-800002 Tel.: 91612-2256999, 91612-2254802 JPS Associates (P) Ltd. New Delhi Acknowledgement We at JPS take opportunity to thank all the officials at WRD namely Mr. Er Indu Bhusan Kumar, Chief Engineer (Planning and Monitoring) Mr. Narendra Prasad Mandal, Additional Project Director (BAPEPS), Official in BAPEPS namely Mr. Ravi Kumar Gupta, State Project Specialist (Environment), Officials at FMISC Mr. A.K.Samaiyar (Ex-Joint Director), Mr. Sitaram Agarwal (Ex-Joint Director), Er. Anil Kumar (Deputy Director I), Mr. Dilip Kumar Singh (Ex-Deputy Director), Mr. Nagan Prasad (Joint Director), Mr. Zakauallah (Asst.Director), Mr. Mukesh Mathur (GIS Expert) and Mr. Syed Niyaz Khurram (Web Master) for their able guidance and constant support to us in the conduct of the assignment in a smooth manner. We are also thankful to WRD field officials Mr. Prakash Das (Chief Engineer), Birpur Division, Mr. Vijender Kumar (Chief Engineer) Samastipur Division, Mr. Vijender Kumar (Executive Er. Birpur Division), Mr. Vinod Kumar (Executive Er. Nirmali Division) and Mr. Mithilesh Kumar (Executive Er.) Jhanjharpur Division and all the Asst. Engineers and the Junior Divisions of all the 11 Field Divisions for their constant support and hospitality to our team of experts and field staff during the conduct of assignment at the field level. Our thanks are also due to SRC members, Mr. Sachidanand Tiwari (Embankment Expert), and Mr. Santosh Kumar (Hydrologist), Mr. Bimalendu Kumar .Sinha, Flood Management Advisor (FMISC) and Mr. S.K. -

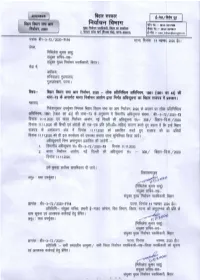

Notification of Result

नबंधन सं या पी0ट0-40 असाधारण अकंं बहार सरकार कािशत 20 काितक 1942 (श0) (सं0 पटना 852) पटना बधु वार 11 नव बर 2020 fuokZpu foHkkx ——— vf/klwpuk 11 uoEcj 2020 laŒ ch1&3&72@2020&73—yksd izfrfuf/kRo vf/kfu;e] 1951 ¼1951 dk 43½ dh /kkjk&73 ds mica/kksa ds vuqlj.k esa sa fcgkj fo/kku lHkk vke fuokZpZ u] 2020 ds s fuokZpZ u ifj.kke ls s laca afa /kr Hkkjr fuokpZZ u vk;ksxs dh vf/klwpw uk laŒa &308@ fcgkj&fo-l-@2020 fnukad 11-11-2020 loZlk/kkj.k dh tkudkjh ds fy, izdkf’kr dh tkrh gSA fcgkj&jkT;iky ds vkns’k lss] fefFkys’k dqekj lkgq] la;qDr lfpo&lg& la;a qDq r e[qq ; fuokpZZ u inkf/kdkjh] fcgkjA 2 बहार गजट (असाधारण), 11 नव बर 2020 Hkkjr fuokZpu vk;ksx ——— vf/klwpuk fuokZpu lnu] v’kksd jksM] ubZ fnYyh&110001@fnukad 11 uoEcj] 2020] 20 dkfrZd] 1942 (’kd) la0 308@fcgkj&fo-l-@2020%&;r—fcgkj jkT; ds jkT;iky }kjk yksd izfrfuf/kRo vf/kfu;e] 1951 ¼1951 dk 43½ dh /kkjk 15 dh mi&/kkjk ¼ 2½ ds v/khu viuh vf/klwpuk la[;k ch1&3&72@2020&30] ch1&3&72@2020&37 ,oe~ ch1&3&72@2020&41 tks dze’k% 1 vDrwcj] 2020] 9 vDrwcj] 2020 ,oa 13 vDrwcj] 2020 dks tkjh dh xbZ Fkh] ds vuqlj.k eas fcgkj jkT; d s fy, ubZ fo/kku lHkk ds xBu d s iz;kstu gsrq lk/kkj.k fuokZpu djk;k x;k( vkSj ;r% mDr lk/kkj.k fuokpZ u eas lHkh fo/kku lHkk fuokZpu {ks=ksa ds fuokZpuksa dk ifj.kke lacaf/kr fuokZph inkf/kdkfj;ksa }kjk ?kkfs ”kr dj fn;k x;k gS; vr%] vc yksd izfrfuf/kRo vf/kfu;e] 1951 ¼1951 dk 43½ dh /kkjk 73 ds vuqlj.k esa] Hkkjr fuokZpu vk;ksx mu fuokZpu {ks=ksa ds fy, fuokZfpr lnL;ksa ds uke] muds lEc) ny lfgr ;fn dksbZ gks] bl vf/klwpuk dh vuqlwph esa ,rn~}kjk vf/klwfpr djrk gSA Hkkjr fuokZpu -

Press Note Bihar 2020

भारत निर्ााचि आयोग ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA Tel. No. 011-23052246 निर्ााचि सदि, Fax 011-23052001 अशोक रोड, िई दद쥍 ली-110001. Website: www.eci.gov.in Nirvachan Sadan, Asoka Road, New Delhi-110001 No. ECI/PN/64/2020 Dated:25th September, 2020 PRESS NOTE Subject: General Election to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar, 2020 -reg. The term of the Legislative Assembly of Bihar is due to expire on 29.11.2020. The term and strength of the assembly is indicated as below: Name of State Term of Assembly No. of Assembly Seats Bihar 30.11.2015 to 29.11.2020 243 81 The Election Commission of India (hereinafter ECI) is committed to hold free, fair and safe election to the Legislative Assembly of Bihar before the cessation of its term, in exercise of the authority and powers conferred upon under Article 324 read with Article 172 (1) of the Constitution of India and Section 15 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951. 1. Assembly Constituencies- The total number of Assembly Constituencies in the State of Bihar and seats reserved for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, as determined by the Delimitation of Parliamentary and Assembly Constituencies Order, 2008, are as under: - State Total No. of ACs Reserved for SCs Reserved for STs Bihar 243 38 2 2. Broad Guidelines to be followed during entire election processes for all persons- 1) Every person shall wear face mask during every election related activity. 2) At the entry of hall/ room/ premises used for election purposes: (a) Thermal Scanning of all persons shall be carried out; (b) Sanitizer shall be made available at all locations. -

Ground Water Information Booklet Darbhanga District, Bihar State

भूजल सूचना पुस्तिका दरभंगा स्जला, बिहार Ground Water Information Booklet Darbhanga District, Bihar State 85°-45' 86°-0' 86°-15' ADMINISTRATIVE MAP BIHAR STATE DARBHANGA DISTRICT, BIHAR. 0 5 10 15 Km Ganga R. Jale Scale Keotiranway 26° 26° 15' 15' Manigachi Singwara DARBHANGA Bahadurpur Alinagar Benipur Hayaghat Ghanshyampur 26° 26° 0' 0' Baheri Goura bouram Kiratpur Biraul LEGEND District Boundary Block Boundary Road Kusheshwar Kusheshwar Railway Asthan Asthan (E) District Headquarter 25° Block Headquarter 25° 45' River 45' 85°-45' 86°-0' 86°-15' के न्द्रीय भमू िजल िो셍 ड Central Ground water Board Ministry of Water Resources जल संसाधन िंत्रालय (Govt. of India) (भारि सरकार) Mid-Eastern Region िध्य-पर्वू ी क्षेत्र Patna पटना मसिंिर 2013 September 2013 1 PREPARED BY - Shri S. Sahu Sc. B UNDER SUPERVISION OF - Shri A.K.Agrawal, Scientist’D’ CARTOGRAPHY - Shri Lokendra Kumar, Draughtsman UPDATED BY - Shri S.N.Dwivedi, Sc-C & Dr. Fakhre Alam, STA (Hg) 2 CONTENTS DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 5 – 6 1. INTRODUCTION 7 - 11 1.1 Location, Area and Population 1.2 Basin/Sub-Basin and Drainage 1.3 Land use, agriculture and irrigation practices 1.4 Studies/Activities carried by CGWB 2. CLIMATE AND RAINFALL 11 - 12 3. GEOMORPHOLOGY AND SOIL 12 - 13 3.1 Geomorphology 3.2 Soil 4. HYDROGEOLOGY 13 - 17 4.1 Water Bearing Formations 4.2 Mode of Occurrence of Ground Water 4.3 Hydraulic Characteristics of Aquifers 4.4 Depth to water level 4.5 Ground Water Quality 5. GROUND WATER RESOURCES 17 - 18 5.1 Status of groundwater development 6. -

2019012384.Pdf

TA- s is C% f l 1 9 61 sn(0, ,Jj PTZM 3 311*2T) 2R PT3T 4T) ^T i^2T^f-u^ a,TJr , ZTT aITJT 2, Ur cf% WT tY, 34 ZF5M 34m- 1 -gM (a^T^?lcfr Af4Ta s ^TL 3T3^T`7Ti a fay -hair %Tu .........................., ...................... .......... f^FTr^ T2IT f^i ^ z 3 a f rF^fi ^? ^ . x ........................ f r/Urrar pjf^f T -diM ..................................................... k............................................... air uar ............................................................ ........... ........................................ 51 .................... '51.................... x artar -go ...........X ........... fa ^iaTr f fi i f ^ rR -*o .......... )c...... w uf^ i air ................................... ............................................ .... ................ SAY' aTr^r )( ................... fatTrT ZTmmr f^ ^^ ^......a -io ....... ...., .............. w s OIW- 2 fie %Tg) ( ^ a f LT afL arau 3u^1^ -cw g.7...^^t31.:^i^c).?i11C .................. fay fdZTTh 793T f ^ f ..... 3TVTeff 6u r 2r^l z^arr f ^ 14-1 r CAAC .. 32 T 31^ gdI ..... n..c^li..-...fit ^.1.-.... ^ .................... ...........................:. ...^.t.-^.t.-..:.^.r.F^•-^f^.'..,...^^' .^ ...............-galT fay tz 4m wrft arraT R0 .....^ .^........ i0...... ... n fr3uz^f^er^zia^^el^f^i^ 3TrT t f B rit ^air2 r 32i fay aTT f 145 iT 3 £ T _42m -C ^ iQ c 3Ttf T I vzqT,ra -4 faf'srf ri3h 3 m z1-j 'i at<41q q \ 61 tt I. RN- 3 ^raTt 2T^ T -Ta -4 ) -4 eufff 3faZT4 WaT T i alrg 2 (mil MJ^ Wf 9t %5 c f^ru 3M4 YZJpJi cf f 3 2 VIZ" w T - (15) .................................14.:S ................. --.OF3rr^ Tr-ft -cb7 ZrT ;Br (I i) 3 al ............................... ................................................... (a) (1)ce VM& c /2T r ZM -9 A7 3QR <'• -jRT -M c5T u MT Wu q -4 ^ err UM I c ^c LJ 3iTJ4 V C gj^, 39ee WT 12 TZr r %MT rT t, ``i zr r i v^l --cc t T ( c^ 3zl > 3i^z .............^.......... -

Annual Work Plan & Budget 2021-22

National Programme of Mid Day Meal in Schools (MDMS) Annual Work Plan & Budget 2021-22 Name of the State: BIHAR Soft copy of this format can be down loaded from www.mdm.nic.in Mid Day Meal Programme Annual Work Plan and Budget 2021-22 (Please do not change serial numbers below) 1. Introduction: 1.1 Brief history National Programme of Nutritional Support to Primary Education (NP-NSPE) was launched as a centrally sponsored scheme on 15th August 1995. 1995-2002 3kg rice to each children per month 2003-04 As Pilot project in 2532 schools of 30 blocks of 10 different district cooked meal started 2005 Mid day meal started in its present form for Class I-V. 2007-08 Mid-day Meal extended to class VI-VIII. 2008 On 21st May Bihar Rajya Madhyan Bhojan Yojana Samiti was registered and came into existence. Objective of Mid-day Meal • Improving the nutritional status of children in classes I – VIII in Government, Local Body and Government aided schools, and EGS and AIE centres. • Encouraging poor children, belonging to disadvantaged sections, to attend school more regularly and help them concentrate on classroom activities • Providing nutritional support to children of primary stage in drought-affected areas during summer vacation Our Goal Each School-Each Working days-Each child Providing Healthy & Nutritious Mid-day Meal. Demographic Profile of the State: Page 2 of 58 Physical Features Latitude 24° 20' 10" 27° 31' 15" N Longitude 83° 19' 50" - 88° 17' 40" E Rural Area 92,257.51 sq. km Urban Area 1,095.49 sq. -

EQ Damage Scenario.Pdf

DAMAGE SCENARIO UNDER HYPOTHETICAL RECURRENCE OF 1934 EARTHQUAKE INTENSITIES IN VARIOUS DISTRICTS IN BIHAR Authored by: Dr. Anand S. Arya, FNA, FNAE Professor Emeritus, Deptt. of Earthquake Engg., I.I.T. Roorkee Former National Seismic Advisor, MHA, New Delhi Padmashree awarded by the President, 2002 Member BSDMA, Bihar Assisted by: Barun Kant Mishra PS to Member BSDMA, Bihar i Vice Chairman Bihar State Disaster Management Authority Government of Bihar FOREWORD Earthquake is a natural hazard that can neither be prevented nor predicted. It is generated by the process going on inside the earth, resulting in the movement of tectonic plates. It has been seen that wherever earthquake occurs, it occurs again and again. It is quite probable that an earthquake having the intensity similar to 1934 Bihar-Nepal earthquake may replicate again. Given the extent of urbanization and the pattern of development in the last several decades, the repeat of 1934 in future will be catastrophic in view of the increased population and the vulnerable assets. Prof A.S.Arya, member, BSDMA has carried out a detailed analysis keeping in view the possible damage scenario under a hypothetical event, having intensity similar to 1934 earthquake. Census of India 2011 has been used for the population and housing data, while the revised seismic zoning map of India is the basis for the maximum possible earthquake intensity in various blocks of Bihar. Probable loss of human lives, probable number of housing, which will need reconstruction, or retrofitting has been computed for various districts and the blocks within the districts. The following grim picture of losses has emerged for the state of Bihar. -

Bihar State Educational Infrastructure Development Corporation

Bihar State Educational Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited, Patna Physical status of Construction of SSSM (Senior Secondary School Minority) 2014-15 Report Date as on : 31/05/2018 Ten Physical Status der Ret Ground Not 1st Floor S.N. Group No. Name of District Name of the Block Name of School en Foun floor Com Remarks Pro Lay- Finis der dati PL plet ces Sta out hing on LL RL LL RL e s rt 1 SSSM-27(A) Araria Forbesganj M. S. Amauna Inaugurated 2017 1 2 SSSM-27(B) Araria Forbesganj M. S. Punardaha Inaugurated 2016 1 3 SSSM-25-1 Araria Narpatganj M. S. Gokhlapur B. M. S. 1 4 SSSM-25-2 Araria Narpatganj M. S. Bela Rifuji Handover 1 5 SSSM-25-3 Araria Narpatganj M. S. Chanda 1 6 SSSM-26(A) Araria Raniganj M. S. Haridayepur Inaugurated 2017 1 Work progress slow by contractor , 3rd 7 SSSM-26(B) Araria Raniganj M. S. Narayanpur 1 debar NOTICE sent to contractor. Work progress slow by contractor , 3rd 8 SSSM-26(C) Araria Raniganj U. M. S. Dumariya Balak 1 debar NOTICE sent to contractor. 9 SSSM-28(A) M. S. Goragachh Inaugurated 2016 Araria Sikti 1 10 SSSM-28(B) U. M. S. Dimhiya Araria Sikti 1 2nd floor lintel level as per G+2 11 SSSM-29 M. S. Pechauli Araria Sikti 1 drawing 12 SSSM-45 (A) Banka Dhuraiya U. M. S. Chalna 1 S. F. Roof Level 13 SSSM-45 (B) Banka Dhuraiya U. M. S. Tahirppura Kanya 1 Debar Page 1 of 12 Ten Physical Status der Ret Ground Not 1st Floor S.N. -

An Introduction to the Maithili Dialect of the Bihari Language As

.^ v \ # <# X # <Ml <%£ <^'' ^ *•£*/•„ y^ V J? <fc 4* <&£&£& '*. 1 X %-f ¥ r e£ <fc '%> f %% f , AN INTRODUCTION TO THK M AIT HI LI DIALECT OK THE BIHARI LANGUAGE AS SPOKEN IN NORTH BIHAR BY GEORGE A. GRIERSON, C.I.E., Ph.D., D.Litt., Honorary Member of tlie Asiatic Society of Bengal, of the American Oriental Society, of the Nugari Pracdritii Sabhd, and of the Soci4t4 Finno- Ougrienne ; Foreign Associate Member of the Society Asiatique de Paris ; Corresponding Member of the Eoniglichc Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Gottingen formerly of His Majesty' s Indian Civil Service. SECOND EDITION. PART I. GRAMMAR. Calcutta PRINTED AT THE BAPTIST MISSION PRESS AND PUBLISHED BY THE ASIATIC SOCIETY, 57. PARK STREET. 1909. tf mi In compliance with current copyright law, U. C. Library Bindery produced this replacement volume on paper that meets ANSI Standard Z39.48- 1984 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original 1998 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION. When I undertook the preparation of this second edition of my Maithili Grammar, my intention was to do little more than to arrange a corrected reprint of the first edition published in 1881. I soon found that the necessary corrections were so heavy and so important that the whole work had to be recast. It has, in fact, been rewritten. When the first edition was prepared, the only specimens of literary Maithili available were those then in my possession, and subsequently published in my Maithili Chrestomathy. Since then more literary materials have been discovered and have been made available to students. These have all been carefully worked through by me, and, as a result, I have been able to give in the present edition of the Grammar a fairly complete set of examples of the manner in which the various forms are employed. -

Annual Report 2016-2017

Annual Report 2016-2017 1. MISSION STATEMENT National Council for Promotion of Urdu Language (NCPUL) started its academic and administrative operations during IX Plan w.e.f. 01.04.1996. NCPUL was declared a national Nodal Agency for promotion of Urdu in the country and recognized as an important autonomous organization of Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India devoted to promotion of Urdu language and mainstreaming of Urdu education. NCPUL has been given the role of networking of Urdu organizations throughout the country so as the policies of the Government could be implemented in all Urdu speaking areas of the country. For past few years NCPUL has emerged as an effective coordination mechanism for promotion of Urdu language and Urdu medium education in India. During the course of discharging its responsibilities, NCPUL has been assigned the additional responsibility of promotion of Arabic & Persian languages which have played an important role in the development of composite culture of India. The broad goals of the Council are as under:- 1) To promote, develop and propagate Urdu language. 2) To take action for making available in Urdu language, the knowledge of scientific and technological development as well as knowledge of ideas evolved in the modern context. 3) To advise the Government of India on issues connected with Urdu language and having bearing on education as may be referred to it. 4) To undertake any other activity for the promotion of Urdu language as may be deemed fit by the Council. 1 2. COMPOSITION: NCPUL has been registered as a Society under the Societies Registration Act 1860.