Uofcpress Landhaschanged 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte Cultural Festival in Igboland, Nigeria

67 International Journal of Modern Anthropology Int. J. Mod. Anthrop. 2020. Vol. 2, Issue 13, pp: 67 - 98 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijma.v2i13.2 Available online at: www.ata.org.tn & https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma Research Article Historical dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte cultural festival in Igboland, Nigeria Akachi Odoemene Department of History and International Studies, Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] (Received 6 January 2020; Accepted 16 May 2020; Published 6 June 2020) Abstract - Ọjị (kola nut) is indispensable in traditional life of the Igbo of Nigeria. It plays an intrinsic role in almost all segments of the people‟s cultural life. In the Ọjị Ezinihitte festivity the „kola tradition‟ is meaningfully and elaborately celebrated. This article examines the importance of Ọjị within the context of Ezinihitte socio-cultural heritage, and equally accounts for continuity and change within it. An eclectic framework in data collection was utilized for this research. This involved the use of key-informant interviews, direct observation as well as extant textual sources (both published and un-published), including archival documents, for the purposes of the study. In terms of analysis, the study utilized the qualitative analytical approach. This was employed towards ensuring that the three basic purposes of this study – exploration, description and explanation – are well articulated and attained. The paper provided background for a proper understanding of the „sacred origin‟ of the Ọjị festive celebration. Through a vivid account of the festival‟s processes and rituals, it achieved a reconstruction of the festivity‟s origins and evolutionary trajectories and argues the festival as reflecting the people‟s spirit of fraternity and conviviality. -

Article Download

wjert, 2018, Vol. 4, Issue 6, 95 -102. Original Article ISSN 2454-695X Ibeje etWorld al. Journal of Engineering World Journal ofResearch Engineering and Research Tech andnology Technology WJERT www.wjert.org SJIF Impact Factor: 5.218 IMPACTS OF LAND USE ON INFILTRATION A. O. Ibeje*1, J. C. Osuagwu2 and O. R. Onosakponome2 1Department of Civil Engineering, Imo State University, P.M.B. 2000, Owerri, Nigeria. 2Department of Civil Engineering, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Nigeria. Article Received on 12/09/2018 Article Revised on 03/10/2018 Article Accepted on 24/10/2018 ABSTRACT *Corresponding Author Land use can affect natural ecological processes such as infiltration. A. O. Ibeje There are many land uses applied at Ikeduru L.G.A. in Imo State, Department of Civil Nigeria, thus, the area is selected as a case study. The objective of Engineering, Imo State University, P.M.B. 2000, study is to determine the effects of land use on infiltration by three Owerri, Nigeria. different land use types; 34 of them are in farmlands, 34 in Bamboo field and 32 in forestlands. Within each land use type, multiple regression are used to determine degree of association between the rates of infiltration, moisture content, porosity, bulk density and particle sizes. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance is used to determine whether significant differences in infiltration rates existed between different land uses. The mean steady state infiltration rate of farmlands, bamboo fields and forestland are 1.98 cm/h, 2.44cm/h and 2.43cm/h respectively. The regression model shows that infiltration rate decreases with increase in moisture content and bulk density but increases with the increase of soil particle sizes and porosity. -

DETERMINATION of the ERODIBILITY STATUS of SOME SOILS in IKEDURU LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA of IMO STATE, NIGERIA Chukwuocha N., *Amangabara G.T., and Amaechi C

International Journal of Geology, Earth and Environmental Sciences ISSN: 2277-2081 (Online) An Open Access, Online International Journal Available at http://www.cibtech.org/jgee.htm 2014 Vol. 4 (1) January-April, pp. 236-243/Chukwuocha et al. Research Article DETERMINATION OF THE ERODIBILITY STATUS OF SOME SOILS IN IKEDURU LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA OF IMO STATE, NIGERIA Chukwuocha N., *Amangabara G.T., and Amaechi C. 1Department of Environmental Technology, Federal University of Technology, PMB 1526 Owerri *Author for Correspondence ABSTRACT Determination of soil erodibility status in four selected communities of Ikeduru LGA was conducted. Soil samples were collected randomly from Cassava farm, Bamboo field, Fallow land and sparse grassland and were analysed for moisture content, particle size distribution, textural class, organic matter content, permeability and aggregate structure using oven drying method, sieve analysis, triangular chart, and permeability/soil type table. Laboratory results were subjected to statistical analyses. Narrow variation was seen in all the particle size distribution (ranged from 25.10 – 35.15) with samples from sparse grass land vegetation having the least value (35.20), samples from cassava farm and bamboo field had their values as 35.15 and 29.40 respectively. The clay, silt and MC had a negative non-significant relationship with the erodibility status with values of correlation -.412, -.532 and -.836 respectively. While sand percentage content had a positive non significant relationship with erodibility factor K having the values of .670. OMC percentage content had a high positive significant relationship with erodibility factor K, with the value of correlation as 1.000**. There was a high level of significance between clay, silt, sand, OMC, and MC with values of correlation as -.753**, -.714**, -.831**, and .955** respectively. -

Academia Arena, 2011:3(9) Htt

Academia Arena, 2011:3(9) htt://www.sciencepub.net Effects of HIV/AIDS on Smallholder Agriculture and Food Security in Imo State, Nigeria *Chikaire, J., *Nnadi F.N., **Orusha, J.O., **Onogu, B. and **Okafor, O.E. *Department of Agricultural Extension. Federal University of Technology, Owerri **Department of Agricultural Science, Alvan Ikoku Federal College of Education, Owerri. e-mail [email protected] Abstract: The HIV/AIDS epidemic is challenging all aspects of the development agenda. The disease has decimated sub-Saharan Africa’s agricultural labour force and will continue to do so for generations, depleting the region of its food producers and farmers. Not only is the epidemic causing severe reversals in development gains, but it is making development interventions impractical. Communities livelihoods are being permanently eroded and assets depleted with the reoccurring periods of sickness and deaths that the epidemic brings. Inspite of its incapacitating effects on agricultural production and rural livelihoods, and of the fact that up to 80% of the people-in the most affected countries depend on agriculture for their subsistence, the agricultural sector has not been as forthcoming and as innovative in its response, as the situation requires. Labour, a much valued human asset and the foundation of development interventions, is becoming scare and this lack of labour strains traditional coping mechanisms and increase vulnerability. This paper thus investigation the areas HIV/AIDS has affected food production, and rural livelihood such as depletion of labour, loss of generational knowledge and skills, loss of income, land inheritance rights of women and youth and decreasing nutritional status of households. -

Cultural Festival in Ezinihitte Mbaise, Imo State

Kola Nut (Oji) Cultural Festival in Ezinihitte Mbaise, Imo State N.C. Ihediwa, V. Nwashindu, and C.M. Onah Department of History and International Studies University of Nigeria, Nsukka Abstract The common saying in Igboland is that every other culture group in Nigeria eats kola nuts, but it is only in Igboland that kola nut oji is not only eaten, but also celebrated. This position is true of the Igbo who do not cultivate kola nuts in abundance as a commercial venture like the Yoruba, but have deep reverence for the fruits because of its significance in the Igbo worldview. The Igbo do not eat this fruit like other groups in Nigeria, who essentially eat it for its sedative qualities as well as a hunger therapy, or who use it because of its role as stimulant and aspirin, nicotine and caffeine put together. The social significance of this fruit has lifted it from a mere unprofitable luxury to a vital necessity in the social and cultural settings of the Igbo, particularly the Ezinihitte Mbaise group in Imo State. Here kola nut cultural festival is celebrated annually and on rotation amongst the sixteen communities that make up the local government council area. The Oji Ezinihitte Mbaise cultural festival is not only an occasion for the communities to examine their progress and challenges, but also one for attracting visitors, friends and well-wishers from far and near to be part of a cultural fiesta that entertains guests to their souls. It is also used as a medium to attract government in their developmental projects as well as brain storm on other possibilities. -

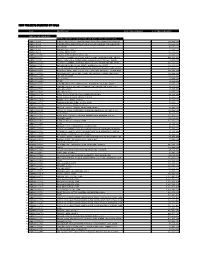

List of Member Banks

ABIA S/N Code Name FI Type Default group State Code State Description Local Gov CodeLocal Gov Description City Code City Description E-mail Phone Address 1 50005 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.08 Isuikwuato 904 Uturu [email protected] 08037731407, 08033062369 Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State 2 50085 Arochukwu Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.03 Arochukwu 180 Arochukwu [email protected] 08065062364, 08036001991 Amaikpe Square, Afor Arochukwu Market, Abia State. 3 51070 Bundi Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.02 Aba South 38 Aba [email protected] 8023409581 157, Cameroun Road, Aba, Abia State 4 50174 Chibueze Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.02 Aba South 38 Aba [email protected] O802228288, 08068588959, 08056620149 CKC, 82 Ehi/Asa Road, Aba, Abia State. 5 50230 Decency Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.16 Umuahia South [email protected] 08052103833, 080370314191 Afor Ibeji Market Square, Old Umuahia, Abia State. 6 50182 East-Gate Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.02 Aba South 38 Aba [email protected] 08034713691, 08037102981 135 Aba-Owerri Road, Aba, Abia State 7 50393 Hitech Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.02 Aba South 38 Aba [email protected] 143, Azikiwe Road, Aba, Abia State 8 50422 Ihechiowa Microfinance Bank Limited MFB.2 Unit 23 ABIA 23.03 Arochukwu 180 Arochukwu [email protected] 07035544414, 08057465298, 08033147575 Umuye Ihechiowa, Arochukwu -

Flooding in Imo State Nigeria: the Socio-Economic Implication for Sustainable Development

Humanities and Social Sciences Letters 2014 Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 129-140 ISSN(e): 2312-4318 ISSN(p): 2312-5659 © 2014 Conscientia Beam. All Rights Reserved FLOODING IN IMO STATE NIGERIA: THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPLICATION FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Duru Pat. N1 --- Chibo Christian N2 1,2Department of Geography and Environmental Management, Imo State University, Owerri ABSTRACT The menace of flooding ravaging different areas of Imo state Nigeria has been a recurrent phenomenon in recent years. This research investigated the socio-economic implications of flooding for sustainable development of the state. The paper aimed at investigating, identifying and documenting the socioeconomic implications of flooding to sustainable development of Imo state. The study tried to identify various locations affected by flooding and also examined the positive and negative effects of flood to the area. 500 copies of questionnaires were distributed using systematic sampling in six local government areas of the state used for pilot survey. About 96.8 percent of the questionnaires was retrieved and used for the study. Collected data were presented using frequency tables, charts and percentages. The study identified various locations affected by flooding, years of severe flooding and also identified various effects of flooding in the state. Finally the paper concluded by making recommendations which includes discouraging development of areas prone to flooding among others. Keywords: Menace, Flooding, Ravaging, Sustanainable development, Socio-economic, Floodplain, Environment. 1. INTRODUCTION Flood is a body of water which rises to overflow land which is not normally submerged. Flood results from a number of causes of which the most important are climatological in nature (Okorie, 2010). -

The Land Has Changed: History, Society and Gender in Colonial Eastern Nigeria

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2010 The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria Korieh, Chima J. University of Calgary Press Chima J. Korieh. "The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria". Series: Africa, missing voices series 6, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2010. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48254 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com THE LAND HAS CHANGED History, Society and Gender in Colonial Eastern Nigeria Chima J. Korieh ISBN 978-1-55238-545-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

National Assembly 1780 2013 Appropriation Federal Government of Nigeria 2013 Budget Summary Ministry of Science & Technology

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT OF NIGERIA 2013 BUDGET SUMMARY MINISTRY OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TOTAL OVERHEAD CODE TOTAL PERSONNEL TOTAL RECURRENT TOTAL CAPITAL TOTAL ALLOCATION COST MDA COST =N= =N= =N= =N= =N= 0228001001 MAIN MINISTRY 604,970,481 375,467,963 980,438,444 236,950,182 1,217,388,626 NATIONAL AGENCY FOR SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING 0228002001 INFRASTRUCTURE (NASENI), ABUJA 653,790,495 137,856,234 791,646,729 698,112,110 1,489,758,839 0228003001 SHEDA SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY COMPLEX - ABUJA 359,567,945 101,617,028 461,184,973 361,098,088 822,283,061 0228004001 NIGERIA NATURAL MEDICINE DEVELOPMENT AGENCY 185,262,269 99,109,980 284,372,249 112,387,108 396,759,357 NATIONAL SPACE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT AGENCY - 0228005001 ABUJA 1,355,563,854 265,002,507 1,620,566,361 2,282,503,467 3,903,069,828 0228006001 COOPERATIVE INFORMATION NETWORK 394,221,969 26,694,508 420,916,477 20,000,000 440,916,477 NATIONAL BIOTECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY - 0228008001 ABUJA 982,301,937 165,541,114 1,147,843,051 944,324,115 2,092,167,166 BOARD FOR TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - 0228009001 ABUJA 178,581,519 107,838,350 286,419,869 351,410,244 637,830,113 0228010001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - AGEGE 72,328,029 19,476,378 91,804,407 25,000,000 116,804,407 0228011001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - ABA 50,377,617 11,815,480 62,193,097 - 62,193,097 0228012001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - KANO 60,891,201 9,901,235 70,792,436 - 70,792,436 0228013001 TECHNOLOGY BUSINESS INCUBATOR CENTRE - NNEWI 41,690,557 10,535,472 52,226,029 - 52,226,029 -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Bank Directory Page 1 S/N Name Staff Staff Position Address Website 1

Bank Directory S/N Name Staff Staff Position Address Website 1 Central Bank Of Nigeria Mr. Godwin Emefiele, Governor Central Business District, Garki, www.cbn.gov.ng HCIB Abuja 2 Nigeria Deposit Insurance Alhaji Umaru Ibrahim, MNI, Managing Plot 447/448, Constitution http://ndic.org.ng/ Corporation FCIB Director/Chief Avenue, Central Business Executive District, Garki, Abuja 3 Access Bank PLC Mr. Herbert Wigwe, FCA Group Managing 1665, Oyin Jolayemi Street, www.accessbankplc.com Director/Chief Victoria Island, Lagos Executive 4 Diamond Bank PLC Mr. Uzoma Dozie, FCIB Group Managing Plot 1261 Adeola Hopewell www.diamondbank.com Director/Chief Street, Victoria Island, Lagos, Executive Lagos , 5 Ecobank Nigeria PLC Mr. Patrick Akinwuntan Group Managing Plot 21, Ahmadu Bello Way, www.ecobank.com Director/Chief Victoria Island, Lagos Executive 6 First City Monument Bank PLC Mr. Adam Nuru Managing Primrose Towers, 6-10 www.fcmb.com Director/Chief Floors ,17A, Tinubu Square, Executive Officer Lagos 7 Fidelity Bank PLC Nnamdi J. Okonkwo Managing 2, Kofo Abayomi Street, Victoria www.fidelitybankplc.com Director/Chief Island, Lagos Executive 8 First Bank Of Nigeria Limited Dr. Adesola Kazeem Group Managing 35, Marina, Lagos www.firstbanknigeria.com Adeduntan, FCA Director/Chief Executive Officer 9 Guaranty Trust Bank PLC (GT Bank) Mr. Olusegun Agbaje, Managing Plot 1669, Oyin Jolayemi Street, www.gtbplc.com HCIB Director/Chief Victoria Island, Lagos Executive 10 Citibank Nigeria Limited Mr. Akin Dawodu MD/CEO Charles S. Sankey House,27 www.citigroup.com Kofo Abayomi Street, Victoria Island, Lagos 11 Keystone Bank LTD Mr. Hafiz Olalade Bakare Managing 1, Keystone Bank Crescent, www.keystonebankng.com Director/Chief Victoria Island Executive Page 1 Bank Directory 12 Polaris Bank PLC Mr. -

Annual Postal Services Data

Annual Postal Services Data (2018) Report Date: July 2019 Data Source: National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) Contents Executive Summary 1 Number of Post Offices and Postal Agencies 2 Number of Postal Articles Handled in 2018 3 Revenue Generated for the Period January - December 2018 4 Summary of Information on Boxes and Private Mail Bag 6 Abia 6 FCT - Abuja 7 Adamawa 8 Akwa -ibom 9 Anambra 10 Bauchi 11 Bayelsa 12 Benue 13 Borno 14 Cross River 15 Delta 16 Ebonyi 17 Edo 18 Ekiti 19 Enugu 20 Gombe 21 Imo 22 Jigawa 23 Kaduna 24 Kano 25 Katsina 26 Kebbi 27 Kogi 28 Kwara 29 Lagos 30 Nasarawa 31 Niger 32 Ogun 33 Ondo 34 Osun 35 Oyo 36 Plateau 37 Rivers 38 Sokoto 39 Taraba 40 Yobe 41 Zamfara 42 Methodology 43 Appendix 44 Acknowledgment / Contact 72 Executive Summary The Nigerian Postal Service earned a total sum of N7.05bn as revenue in 2018. EMS/Speedpost generated the highest amount of revenue of N1.84bn representing about 26.16% of the total revenue generated in the year. Parcel clearance/delivery fee, stamp proceeds and international mail income followed closely with N1.60bn, N1.04bn and N560.96m revenues generated representing 22.76%, 14.77% and 7.95% of the total revenue generated respectively. The agency handled a total of 20,117,730 mails domestically and internationally in 2018. 9,264,957 mails which represent about 46.05% of the total mails were handled locally while 2,499,631 mails which represent about 12.43% of the total mails were dispatched abroad.