IJMRA-15141.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minor Mineral Quarry Details: Ranni Taluk, Pathanamthitta District

Minor Mineral Quarry details: Ranni Taluk, Pathanamthitta District Sl.No Code Mineral Rocktype Village Locality Owner Operator 1 94 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Athikayam Chembanmudi Tomy Abraham, Manimalethu, Vechoochira , Ranni, Tomy Abraham, Manimalethu, Vechoochira , Ranni, Kuriakose Sabu, Vadakkeveli kizhakkethilaya kavumkal, Kuriakose Sabu, Vadakkeveli kizhakkethilaya kavumkal, 2 444 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Athikayam Chembanoly Angadi P.O., Ranni Angadi P.O., Ranni Kuriakose Sabu, Vadakkevila kizhakkethilaya, Kuriakose Sabu, Vadakkevila kizhakkethilaya, kavumkal, 3 445 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Athikayam Chembanoly kavumkal, Angadi P.O., Ranni. Angadi P.O., Ranni. Aju Thomas, Kannankuzhayathu Puthenbunglow, Aju Thomas, Kannankuzhayathu Puthenbunglow, 4 506 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Athikayam Unnathani Thottamon, Konni Thottamon, Konni 5 307 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Cherukole Santhamaniyamma, Pochaparambil, Cherukole P.O. Chellappan, Parakkanivila, Nattalam P.O., Kanyakumari 6 315 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Cherukole Kuttoor Sainudeen, Chakkala purayidam, Naranganam P.O. Sainudeen, Chakkala purayidam, Naranganam P.O. 7 316 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Cherukole Kuttoor Chacko, Kavumkal, Kuttoor P.O. Chacko, Kavumkal, uttoor P.O. 8 324 Granite(Building Stone) Charnockite Cherukole Nayikkan para Revenue, PIP Pamba Irrigation Project Pampini/Panniyar 9 374 Granite(Building Stone) Migmatite Chittar-Seethathode Varghese P.V., Parampeth, Chittar p.O. Prasannan, Angamoozhy, -

Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (Scsp) 2014-15

Government of Kerala SCHEDULED CASTE SUB PLAN (SCSP) 2014-15 M iiF P A DC D14980 Directorate of Scheduled Caste Development Department Thiruvananthapuram April 2014 Planng^ , noD- documentation CONTENTS Page No; 1 Preface 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Budget Estimates 2014-15 5 4 Schemes of Scheduled Caste Development Department 10 5 Schemes implementing through Public Works Department 17 6 Schemes implementing through Local Bodies 18 . 7 Schemes implementing through Rural Development 19 Department 8 Special Central Assistance to Scheduled C ^te Sub Plan 20 9 100% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 21 10 50% Centrally Sponsored Schemes 24 11 Budget Speech 2014-15 26 12 Governor’s Address 2014-15 27 13 SCP Allocation to Local Bodies - District-wise 28 14 Thiruvananthapuram 29 15 Kollam 31 16 Pathanamthitta 33 17 Alappuzha 35 18 Kottayam 37 19 Idukki 39 20 Emakulam 41 21 Thrissur 44 22 Palakkad 47 23 Malappuram 50 24 Kozhikode 53 25 Wayanad 55 24 Kaimur 56 25 Kasaragod 58 26 Scheduled Caste Development Directorate 60 27 District SC development Offices 61 PREFACE The Planning Commission had approved the State Plan of Kerala for an outlay of Rs. 20,000.00 Crore for the year 2014-15. From the total State Plan, an outlay of Rs 1962.00 Crore has been earmarked for Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP), which is in proportion to the percentage of Scheduled Castes to the total population of the State. As we all know, the Scheduled Caste Sub Plan (SCSP) is aimed at (a) Economic development through beneficiary oriented programs for raising their income and creating assets; (b) Schemes for infrastructure development through provision of drinking water supply, link roads, house-sites, housing etc. -

Icdsproiectsafterre-Orqanisation

~\/ , ,t I ' .. G!&b(() ~ rroroc£rn)~(0 , rroolCf) 0.00 rroof1lJaOj<8dMjm OJc&3~:r - rroo<l!(D)Omf]CIDu6!CJl)6oJlc&<mm<l!ffi)OJmnJBJ.)arl] - <l!6QPcOO"nJ6rnlJOcOJC5mlc&~6)S nJ6m:m>ooeJ S m-6)otj)mfI aill omen) <l!lnJO~~.?,c&cm nJlm:tdDm'dDaS1_!~r@cm!>COOJunJ606)~sln.fl~em6- f --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ffi)O~aOJ<I!db9:lQ)(~)OJdbli;tf:) rro.@.(oij)o.OB)<mJmo. 96/201 O/<mOQldb9:lCllcID'lwasfl,cIDlcoc!OJmmnnJ6cooJ5-12-10 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- nJcoom(OCJl)O: 1) 31-07-2010 -6>~ rro.~(amo.amrroJ mo.46/2010/rroo<EdM.1("l.! 2) 02-07-2010 6>~ rro.@(o.Jl)mo.139/10/CIDrroJ@0J 3) <molDJaOJ<I!dMjmCU>WO~066>S6-12-2010 6>~ 6>affi.mfI.ru5J.nmen)/6Yl11f~38611/1QmmJeo dDwrIDu . .U I IDM1!)II)d.i . -'l\ ~rmoo0eJ3 6>amm51aillammr Qj1«brromcorn516>~ @oCf)mo<!ill<EdblmrrorocOO:Jrocammd, OJ c3L~ 95 6>ammflruJ1o.(j)crou <ElnJ:)@ig~l db ~6>S loJClJ mcm!>mo (G'@)roo@lcOOJ(IT) cIDlmlo armCll~:)OJCJl)jmoav CID<m"cIDldbdbcJDrro~~cOO3emcIDlm6~ @C06TYx)m6mcIDl o.Jco:Jm(OCJl)o 1-6>~ @cm!>coOJulnJdDOCOo marndDldDav.?,6TY5::>~. <E6'Qd:JcOO"nJ6mJ:JCW (!frn)ldbcf6 nJ~m :<mooeJ SI CJ:llcOO.?,emrnfIm3° oJ6cIDlav': <l!6'Qd:JcOO' oJ6mJ:J av(!frn)u coJo.1Idb «>1 coo,sffi1cIDlmc\° nJ«)~QHr,(f()o 2 lnJc£b::>«>O rroroc.$)O«> <mCiffi3mcIDlmaiOdbi<nf!§66T1'"i'.!?l?"'-' <m:JaO.!1Jmjwruflaf6mJ~oJ1eJ~ 6>%)crolru5Jbmcro <l!loJO~~6cfhW nJ3m:ldhm"ldhfo! cOOlem arl]mlo nJ3CID.?,CIDO<n51«rrI)mlOJc31.!1J 6>ommfl cu5)Q{j)mr,G!lnJ02!i!&a3c£bOOldbmidDc61 c003emcIDlm6~ <1!loJoQl<Jjo<marnnJcoom(Oooo3-6>~ c&{dmu lnJ&bOCOo <mO~C1.oJ Qlc&mmcu>avo~m <mm(Oili"I4Jl. -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

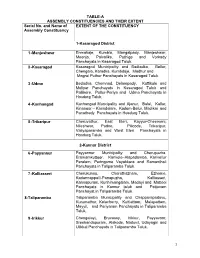

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

DEPARTMENT of HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION 9 Physics

No. EX II (2)/00001/HSE/2017 DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM - MARCH 2017 LIST OF EXTERNAL EXAMINERS (Centre wise) 9 Physics District: Pathanamthitta Sl.No School Name External Examiner External's School No. Of Batches 1 03001 : GOVT. BHSS, ADOOR, BEENA G 03031 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N V HSS, ANGADICAL SOUTH, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04734285751, 9447117229 <=15 2 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, MANJU.V.L 03041 8 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Junior (Physics) K.R.P.M. HSS, SEETHATHODE, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9495764711 <=15 3 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, THOMAS CHACKO 03010 4 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT BOYS Ph: Ph: , 9446100754 HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA,PATH ANAMTHITTA 30 4 03003 : GOVT. HSS, BIJU PHILIP 03050 6 EZHUMATTOOR, HSST Senior (Physics) TECHNICAL HSS, MALLAPPALLY EAST.P.O, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: 04812401131, 9447414839 10 Ph: PATHANAMTHITTA, 689584 5 03004 : GOVT.HSS, SHEEBA VARGHESE 03045 7 KADAMMANITTA, HSST Senior (Physics) MT HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: , 9447223589 10 Ph: 6 03005 : K annasa Smaraka GOVT HSS, JESSAN VARUGHESE 03016 8 KADAPRA, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) M G M HSS, THIRUVALLA, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04692702200, 9496212211 10 7 03006 : GOVT HSS, KALANJOOR, LEKSHMI.P.S 03009 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT HSS KONNI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9447086029 14 8 03007 : GOVT HSS, VECHOOCHIRA RAJIMOL P R 03026 4 COLONY, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N D P HSS, VENKURINJI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04735266367, 9495554912 <=15 9 03008 : GOVT -

District Census Handbook

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-B SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 5 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 7 5 Brief History of the District 9 6 Administrative Setup 12 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 14 8 Important Statistics 16 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 20 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 25 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 33 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 41 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 49 (vi) Sub-District Primary Census Abstract Village/Town wise 57 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 89 Gram Panchayat Primary Census Abstract-C.D. -

St. Thomas College, Ranni Affiliated to Mahatma Gandhi University

St. Thomas College, Ranni Affiliated to Mahatma Gandhi University St. Thomas College, Ranni invites applications for skill development - one year diploma and six months certificate courses - under UGC - National Skill Qualification Framework (NSQF) Scheme. ADMISSIONS OPEN SKILL Eligibility Key Features DEVELOPMENT Higher Secondary or Regular Course Diploma pass or Specialised job training by professionals DIPLOMA AND equivalent Field visits and Internships CERTIFICATE Age limit: Maximum 30 MoUs and Collaborations with industries years and experts COURSES UNDER UGC-NSQF Diploma Courses LAST DATE FOR REGISTRATION : 23/11/2020 Yoga CONTACT US Mushroom Cultivation Technology Certificate Courses www.st.thomascollegeranni.com 9605007432, 6282689757, 9745234303 Plant Tissue Culture Rubber Laboratory St. Thomas College Technology Chemist Ranni Pathanamthitta Kerala-689673 Data Science and Waste Management Analytics [email protected] For registration click the link given below Practical Accounting, Artificial Intelligence and Tax Practice and Tally Machine Learning Registration Link Diploma in Yoga Diploma in Edible Mushroom Cultivation Technology Yoga Instructors in Schools in Kerala and outside state Mushroom cultivation is a process of utilizing waste materials to Yoga trainers in Health Centers produce a delicious and nutritious food. Yoga Therapists in Ayurveda Hospitals Through this diploma course, we focus to train unemployed Yoga Therapists in Hotels and Resorts, youth for their socio-economic fortification by educating them different aspects of mushroom cultivation. Diploma in plant tissue culture technology Diploma in waste management In Tissue culture, under the strict aseptic condition, an entire plant can be regenerated from a single cell. Apart from their use as a tool of research, now a days, it gained industrial importance. -

Pathanamthitta Dt(Std Code- 0468 )

DISTRICT FUNCTIONARIES PATHANAMTHITTA DT(STD CODE- 0468 ) DESIGNATION OFFICE PHONE/FAX MOBILE(CUG) E-MAIL ID DISTRICT COLLECTOR 0468 2222505 0468 2220195 9447029008 [email protected] DISTRICT POLICE CHIEF 0468 2222536 9497996983 [email protected] DY. COLLECTOR(ELECTION) 0468 2224256 0468 2320940 8547610037 [email protected] JS (ELECTION) ELECTION ASSISTANT 0468 2224256 0468 2320940 9495435902 [email protected] CORPORATION NO &NAME OF LB RO, ERO, DESIGNATION OFFICE MOBILE E-MAIL ID SECRETARY PHONE/FAX (CUG) Ros NIL ERO SECRETARY MUNICIPALITIES NO &NAME OF LB RO, ERO& DESIGNATION OFFICE MOBILE E-MAIL ID SECRETARY PHONE/FAX (CUG) Revenue Divisional Officer, RO Adoor 04734 224827 9447799827 [email protected] M 08 Adoor ERO&SECRETARY Secretary, Municipality 0473 42226018 [email protected] District Soil Conservation Officer, RO Pathanamthitta 0468 2224070 [email protected] M 09 Pathanamthitta pathanamthittamunicipality2011@gmail ERO&SECRETARY Secretary, Municipality 0468 2222249 .com Deputy Director of Education, RO Thiruvalla 0469 2600181 [email protected] M 10 Thiruvalla Revenue Divisional Officer, Thiruvalla 0469 2601202 9447114902 [email protected] ERO&SECRETARY Secretary, Municipality 0469 2602486 [email protected] SC Development Officer, RO Pathanamthitta 0468 2322712 [email protected] M 61 Pandalam ERO&SECRETARY Secretary, Municipality 0473 4252251 [email protected] DISTRICT PANCHAYAT NO &NAME OF LB RO, DESIGNATION OFFICE MOBILE E-MAIL ID SECRETARY PHONE/FAX (CUG) RO District Collector,Pathanamthitta -

Panchayat/Municipality/Corp Oration

PMFBY List of Panchayats/Municipalities/Corporations proposed to be notified for Rabi II Plantain 2018-19 Season Insurance Unit Sl State District Taluka Block (Panchayat/Municipality/Corp Villages No oration) 1 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Kanjiramkulam All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 2 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Karimkulam All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 3 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Athiyanoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 4 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Kottukal All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 5 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Athiyannoor Venganoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 6 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Kizhuvilam All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 7 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Mudakkal All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 8 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Anjuthengu All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 9 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Chirayinkeezhu All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 10 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Kadakkavoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 11 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Chirayinkeezhu Vakkom All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 12 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Madavoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 13 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Pallickal All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 14 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Kilimanoor All Villages in the Notified Panchayats 15 Kerala Thiruvananthapuram Kilimanoor Nagaroor All Villages -

A Study from Flood Affected Areas in Ranni and Seasonal Water

Journal of Pediatric Neurology Resources, and Recycling Medicine and waste Management Pollution of Water bodies – A study from flood affected areas in Ranni and Seasonal water quality analysis of Pampa river from Erumely (Kottayam District) and Ranni (Pathanamthitta District), Kerala, India Dr.R.Aruna Devy Department of Zoology, St.Thomas College, Ranni, PathanmathittaDist., Kerala, India PIN – 689673 Abstract: Physical and chemical parameters degrade water causing health issues in living organisms. The present study examines the variation in these parameters in Pampa River at Ranny. Water were collected from five different sources at Mamukku,Ranny and tested at CEPCI Kollam. The study showed that the water quality at Ranny is fit for domestic use in terms of heavy metals. But BOD levels were elevated due to the pressure of organic waste that could have been entered due to the presence of chemical and sewage wastes in water bodies at Ranny. Among the five heavy metals (Cadmium, Chromium, Lead, Mercury and Copper) Copper and Chromium were below the standard limit and the other three heavy metals Lead, Cadmium and Mercury was below detected level.The regular water treatment methods adopted in the area due to recent flood may be the result of water quality in Ranny with respect to heavy metals. The physical parameters like pH of water sources in Ranny is normal except well water which slightly acidic due to chemicals runoff and wastewater discharge. The TDS levels are normal in all five sources but BOD levels are elevated due to the presence of organic wastes entered from chemical and sewage disposal in water bodies. -

Cluster Vise

OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR OF GENERAL EDUCATION Higher Secondary Wing ONE DAY CE WORKSHOP RP LIST District : .PATHANAMTHITTA Name of Training Schools in the below Resource Persons Name and School Address Phone No. Subject centre & School code mentioned sub district/ Education Sl.No. district 1 Asharafshah C M Govt HSS Konni 9447047820 GOVT BHSS ADOOR 3001 2 Raveendra Kurup, Govt HSS Elimullumplackal 9496849241 English ADOOR AND PANDALAM SUB DISTRICT 3 Sheeba George, Govt HSS Kadumeenchira 9544407945 MGM HSS THIRUVALLA3016 Mary Philipose Tharakan , Catholicate HSS THIRUVALLA AND MALLAPALLY SUB 4 Pathanamthitta 9497812070 English DIST. 5 Rakhi Sudhakar, Sndp HSS Chenneerkara 9495435367 ST. THOMAS HSS KOZHENCHERY, ARANMULA AND KOZHENCHERY3022 PULLAD SUB DIST. 6 Sreekumar K MpvHSS Kumbazha Pta 9961045004 English 9074321913 7 Suma M S, Govt H S S KONNI CATHOLICATE HSS PATHANAMTHITTA 3023 KONNI AND PATHANAMTHITTTA SUB 8 Rajeev S Amrutha VHSS Konni 9446467163 English DISTRICT 9 Susan Kuruvila, MG HSS Thumpamon 9495718107 ST. JOHNS HSS ERAVIPEROOR3036 RANNI AND VENNIKULAM SUB 10 Aswathy Checha Varghese, SCS HSS Thiruvalla 944721997 English DISTRICT SUB DISTRICT 11 ANEESHKUMAR C R, Govt HSS Kadumeenchira 9446202955 ST.JOHNS HSS ERAVIPEROOR THIRUVALLA EDN DISTRICT 3036 12 Abraham K J, Nethaji HSS Pramadom 9947666352 Malayalam 13 Shyni S G, Govt HSS, Konni 9496196162 MARTHOMA HSS PATHANAMTHITTA EDN DISTRICT PATHANAMTHITTA 3045 9746109023 14 Dr. Indu, Govt HSS Thekkuthode Malayalam 15 Sajayan R, Govt HSS Kalanjoor 9497614133 GOVT HSS OMALLOORE 3013 PATHANAMTHITTA EDN DISTRICT 16 Dr. Ambili, Govt Boys HSS Adoor 9846388571 Hindi 17 Salu Mathew, Govt HSS Chittar 9447449392 MGM HSS THIRUVALLA3016 THIRUVALLA EDN DISTRICT 18 Jayakumari NSS HSS Kunnamthanam Hindi 19 SUJA SARA JOHN ST.