American Life in the Seventeenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

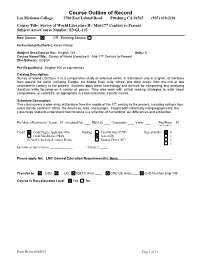

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

Chesapeake Bay and the Restoration Colonies by 1700, the Virginia Colonists Had Made Their Fortunes Primari

9/24: Lecture Notes: Chesapeake Bay and the Restoration Colonies By 1700, the Virginia colonists had made their fortunes primarily through the cultivation of tobacco, setting a pattern that was followed in territories known as Maryland and the Carolinas. Regarding politics and religion: by 1700 Virginia and Maryland, known as the Chesapeake Colonies, differed considerably from the New England colonies. [Official names: Colony and Dominion of Virginia (later the Commonwealth of Virginia) and the Province of Maryland] The Church of England was the established church in Virginia, which meant taxpayers paid for the support of the Church whether or not they were Anglicans. We see a lower degree of Puritan influence in these colonies, but as I have mentioned in class previously, even the term “Puritan” begins to mean something else by 1700. In the Chesapeake, Church membership ultimately mattered little, since a lack of clergymen and few churches kept many Virginians from attending church on a regular basis, or with a level of frequency seen in England. Attending church thus was of somewhat secondary importance in the Virginia colony and throughout the Chesapeake region, at least when compared to the Massachusetts region. Virginia's colonial government structure resembled that of England's county courts, and contrasted with the somewhat theocratic government of Massachusetts Bay and other New England colonies. And again, they are Theocratic – a government based on religion. Now even though they did not attend church as regularly as those living in England, this does not mean that religion did not play a very important role in their lives. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Reading the Remains of the 17Th Century

AnthroNotes Volume 28 No. 1 Spring 2007 WRITTEN IN BONE READING THE REMAINS OF THE 17TH CENTURY by Kari Bruwelheide and Douglas Owsley ˜ ˜ ˜ [Editor’s Note: The Smithsonian’s Department of Anthro- who came to America, many willingly and others under pology has had a long history of involvement in forensic duress, whose anonymous lives helped shaped the course anthropology by assisting law enforcement agencies in the of our country. retrieval, evaluation, and analysis of human remains for As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the identification purposes. This article describes how settlement of Jamestown, it is clear that historians and ar- Smithsonian physical anthropologists are applying this same chaeologists have made much progress in piecing together forensic analysis to historic cases, in particular seventeenth the literary records and artifactual evidence that remain from century remains found in Maryland and Virginia, which the early colonial period. Over the past two decades, his- will be the focus of an upcoming exhibition, Written in Bone: torical archaeology especially has had tremendous success Forensic Files of the 17th Century, scheduled to open at the in charting the development of early colonial settlements Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in No- through careful excavations that have recovered a wealth vember 2008. This exhibition will cover the basics of hu- of 17th century artifacts, materials once discarded or lost, man anatomy and forensic investigation, extending these and until recently buried beneath the soil (Kelso 2006). Such techniques to the remains of colonists teetering on the edge discoveries are informing us about daily life, activities, trade of survival at Jamestown, Virginia, and to the wealthy and relations here and abroad, architectural and defensive strat- well-established individuals of St. -

Medieval Or Early Modern

Medieval or Early Modern Medieval or Early Modern The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton Medieval or Early Modern: The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Ronald Hutton and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7451-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7451-9 CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Ronald Hutton Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 From Medieval to Early Modern: The British Isles in Transition? Steven G. Ellis Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 29 The British Isles in Transition: A View from the Other Side Ronald Hutton Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 42 1492 Revisited Evan T. Jones Chapter Five ............................................................................................. -

The Southern Colonies in the 17Th and 18Th Centuries

AP U.S. History: Unit 2.1 Student Edition The Southern Colonies in the 17th and 18th Centuries I. Southern plantation colonies: general characteristics A. Dominated to a degree by a plantation economy: tobacco and rice B. Slavery in all colonies (even Georgia after 1750); mostly indentured servants until the late-17th century in Virginia and Maryland; increasingly black slavery thereafter C. Large land holdings owned by aristocrats; aristocratic atmosphere (except North Carolina and parts of Georgia in the 18th century). D. Sparsely populated: churches and schools were too expensive to build for very small towns. E. Religious toleration: the Church of England (Anglican Church) was the most prominent F. Expansionary attitudes resulted from the need for new land to compensate for the degradation of existing lands from soil-depleting tobacco farming; this expansion led to conflicts with Amerindians. II. The Chesapeake (Virginia and Maryland) A. Virginia (founded in 1607 by the Virginia Company) 1. Jamestown, 1607: 1st permanent British colony in New World a. Virginia Company: joint-stock company that received a charter from King James I in 1606 to establish settlements in North America. Main goals: Promise of gold, conversion of Amerindians to Christianity (like Spain had done), and new passage through North America to the East Indies (Northwest Passage). Consisted largely of well-to-do adventurers. b. Virginia Charter Overseas settlers were given same rights of Englishmen in England. Became a foundation for American liberties; similar rights would be extended to other North American colonies. 2. Jamestown was wracked by tragedy during its early years: famine, disease, and war with Amerindians a. -

8/21/16 1 I. the Unhealthy Chesapeake • Life in the American

8/21/16 1 2 I. The Unhealthy Chesapeake • Life in the American wilderness: –Life was nasty, brutish, and short. –Malaria, dysentery, and typhoid took their toll. –Newcomers died ten years earlier. –Half of the people born in early Virginia and Maryland died before their twentieth birthday. –Few lived to see their fiftieth birthday, sometimes even their fortieth, especially if they were women. 3 I. The Unhealthy Chesapeake (cont.) • Settlements of the Chesapeake grew slowly, mostly by immigration: –Most were single men in their late teens and early twenties. –Most died soon after arrival. –Men outnumbered women, usually six to one. –Families were few and fragile. –Most men could not find mates. » » » 4 I. The Unhealthy Chesapeake (cont.) • Chesapeake settlements (cont.): – Most marriages were destroyed by death of a partner within seven years. – Scarcely any children reached adulthood under the care of two parents. – Many pregnancies among unmarried young girls reflected weak family ties. • Yet the Chesapeake colonies struggled on. • End of 17th c., white population was growing. • • » 5 II. The Tobacco Economy • Chesapeake hospitable to tobacco growing: –It quickly exhausted the soil. 1 –It created an insatiable demand for new land. 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 1 2 3 4 • Yet the Chesapeake colonies struggled on. • End of 17th c., white population was growing. 8/21/16 • • » 5 II. The Tobacco Economy • Chesapeake hospitable to tobacco growing: –It quickly exhausted the soil. -

British Pamphlets, 17Th Century

British Pamphlets, 17th Century Court of Honour, or, The Vertuous Protestant’s Looking Glass. 1679. Case Y 194 .785. The Newberry has more than 2,200 pamphlets published in Great Britain during the Stuart period (1600-1715). The subjects covered in these pamphlets are varied and include the Civil War, Church of England doctrines, Acts of Parliament, and the Popish Plot. There are collections of pamphlets about the Stuart era monarchs as well as Cromwellian pamphlets. There are pamphlets in the form of letters, sermons, political verse, and drama. Authors include Defoe, Hobbes, Swift, Milton, Pepys. While the collection is rich, finding pamphlets can be a challenge. Searching the Online Catalog The online catalog is the best place to start your search for seventeenth century British pamphlets. If you know the title or author of a given pamphlet, try searching under those headings to start. Many pamphlets are bound with pamphlets of similar themes, so it can be difficult to find individual pamphlets by title or author. Often subject searches retrieve the largest number of relevant pamphlets. A variety of different subject headings are used in the online catalog. They follow the following patterns: Great Britain—History—[range of years]—Pamphlets Example: Great Britain History 1660-1688 Pamphlets Great Britain—Politics and Government—[range of years]—Pamphlets Example: Great Britain Politics and Government 1603-1714 Pamphlets Great Britain—History—[name of monarch]—Pamphlets Example: Great Britain History Charles II Pamphlets In the cases where pamphlets cannot be found using these searches, try the “Advanced Search” option, and set limits on the language and year(s) of publication. -

17Th Century Weston (PDF)

A Weston Timeline (Taken from Farm Town to Suburb: the History and Architecture of Weston, Massachusetts, 1830-1980 by Pamela W. Fox, 2002) Map of the Watertown Settlement (from Genealogies of the Families and Descendants of the Early Settlers of Watertown, Massachusetts. Vol 1, by Henry Bond, M.D. 17th CENTURY 1630 Sir Richard Saltonstall and Rev. George Phillips lead a company up the Charles River to establish the settlement of Watertown, which included what is now Watertown, Waltham, Weston, and parts of several adjoining towns. Weston was known as Watertown Farms or the Farm Lands. Below: Sir Richard Saltonstall 1642 First allotments of land in the Farm Lands. Settlers used the land primarily for grazing cattle. 1673 Approximate time when farmers began to take up residence in what is now Weston. On Sundays, they traveled nearly seven miles from The Farms to the Watertown church. 1673 First post rider is dispatched from New York City to Boston, traveling over mostly Indian trails. Weston was located on the Upper Road, the most popular of three “post roads” used by travelers. 1679 Richard Child establishes a gristmill at Stony Brook near what is now the Waltham town line. Later a sawmill at the same location was used to saw timber for the early houses of Weston. 1695 Weston farmers begin building their own crude, 30-foot-square “Farmers’ Meeting House.” c. 1696 One Chestnut Street House has long been considered the oldest house remaining in Weston. The house was originally “one over one” room. 1698 The General Court grants settlers their formal petition to establish a separate Farmers’ Precinct, also referred to as the Third Military Precinct, the precinct of Lt. -

Early Modern Asia Can We Speak of an ‘Early Modern’ World?

> Comparative Intellectual Histories of Early Modern Asia Can we speak of an ‘early modern’ world? To speak of an ‘early modern’ world raises three awkward problems: the problem of early modernity, the problem of comparison and the problem of globalisation. In what follows, a discussion of these problems will be combined with a case study of the rise of humanism. Peter Burke (rationality, individualism, capitalism, distance’, it is probably best to describe ered at the end of the 15th century). Fol- The ethical wing has been discussed by and so on). the early modern period as at best a lowing the shock of the French invasion Theodore de Bary and others who note The Concept A major problem is the western ori- time of ‘proto-globalisation’, despite the of Italy in 1494, some leading human- the concern of Confucius (Kongzi) and The concept ‘early modern’ was origi- gin of the conceptual apparatus with increasing importance of connections ists, notably Machiavelli, shifted from a his followers and of ‘neo-confucians’ nally coined in the 1940s to refer to a which we are working. As attempts to between the continents, of economic, concern with ethics to a concern with like Zhu Xi with the ideal man, ‘princely period in European history from about study ‘feudalism’ on a world scale have political and intellectual encounters, politics. man’ or ‘noble person’ (chunzi) and also 1500 to 1750 or 1789. It became widely shown, it is very difficult to avoid circu- not only between the ‘West’ and the On the other side, we find the philolo- with the cultivation of the self (xiushen). -

Virginia Development, 1642-1705

VIRGINIA DEVELOPMENT, 1642-1705 I. Virginia at the time of Sir William Berkeley’s arrival (1642) A. Although the tobacco boom time that had caused the company’s failure in 1624 ended around 1630 - the colony continued to develop slowly during the first half of the seventeenth century. B. By 1642, when Governor Sir William Berkeley arrived, the colony remained a sickly settlement with only 8,000 people living there. C. Virginia had earned the reputation “that none but those of the meanest quality and corruptest lives went there.” D. The quality of life in early Virginia was more like a modern military outpost or lumber camp than a permanent society. E. Its leaders were rough, violent, hard-drinking men. Berkeley’s predecessor, Governor John Harvey, had knocked out the teeth of a councilor with a cudgel, before being thrust out himself by the colonists. F. The colony was in a state of chronic disorder. Its rulers were unable to govern, its social institutions were ill-defined, its economy was undeveloped, its politics were unstable, and its cultural identity was indistinct. (Above points from Fischer, Albion’s Seed, 210). II. Berkeley’s and his elite A. In the thirty five years of Sir William Berkeley’s tenure, Virginia was transformed. (1642-76) 1. Its population increased fivefold from 8,000 to 40,000 inhabitants. a. increased immigration b. People were living longer because there were more doctors, better diet (esp. fruit), better conditions on the trip over 2. It developed a coherent social order, a functioning economic system, and a strong sense of its own special folkways. -

GREECE Athens

EXPERT GUEST LECTURER Dear Member, It is with pleasure and excitement that I invite you to join me on a magical springtime journey to Greece and the Greek islands at the time of year when the entire country becomes a vast natural garden. Greece is home to a stunning number of plant species, comprising the richest flora in Europe. More than 6,000 species thrive here, of which about ten percent are unique and can be found nowhere else in the world. This is also the land that gave birth to the science of botany, beginning in the 4th century BC. Ancient Athenians planted the Agora with trees and plants and created leisure parks, considered to be the first public gardens. On this springtime journey we will witness the beautiful display of wild flowers that cover the land as we explore ancient sites, old villages and notable islands. We start in Athens, the city where democracy and so many other ideas and concepts of the Western tradition had their origins, where we will tour its celebrated monuments and witness its vibrant contemporary culture. From Athens, we will continue to Crete, home of the Minoans, who, during the Bronze Age, created the first civilization of Europe. Our three days on this fabled island will give us time to discover leisurely its Minoan palaces, see treasures housed in museums, explore the Dr. Sarada Krishnan is Director of Horticulture magnificent countryside and taste the food, considered to be the source of the widely-sought and Center for Global Initiatives at Denver Mediterranean diet.