Environmental Change in 17Th Century Barbados

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

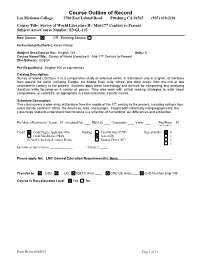

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181

Course Outline of Record Los Medanos College 2700 East Leland Road Pittsburg CA 94565 (925) 439-2181 Course Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Subject Area/Course Number: ENGL-145 New Course OR Existing Course Instructor(s)/Author(s): Karen Nakaji Subject Area/Course No.: English 145 Units: 3 Course Name/Title: Survey of World Literature II: Mid-17th Century to Present Discipline(s): English Pre-Requisite(s): English 100 or equivalency Catalog Description: Survey of World Literature II is a comparative study of selected works, in translation and in English, of literature from around the world, including Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other areas, from the mid or late seventeenth century to the present. Students apply basic terminology and devices for interpreting and analyzing literature while focusing on a variety of genres. They also work with critical reading strategies to write about comparisons, or contrasts, as appropriate in a baccalaureate, transfer course. Schedule Description: This class covers a wide array of literature from the middle of the 17th century to the present, including authors from every literate continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Taught both historically and geographically, the class helps students understand how literature is a reflection of humankind, our differences and similarities. Hrs/Mode of Instruction: Lecture: 54 Scheduled Lab: ____ HBA Lab: ____ Composition: ____ Activity: ____ Total Hours 54 (Total for course) Credit Credit Degree Applicable -

Downloaded4.0 License

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 39–74 nwig brill.com/nwig A Disagreeable Text The Uncovered First Draft of Bryan Edwards’s Preface to The History of the British West Indies, c. 1792 Devin Leigh Department of History, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA [email protected] Abstract Bryan Edwards’s The History of the British West Indies is a text well known to histori- ans of the Caribbean and the early modern Atlantic World. First published in 1793, the work is widely considered to be a classic of British Caribbean literature. This article introduces an unpublished first draft of Edwards’s preface to that work. Housed in the archives of the West India Committee in Westminster, England, this preface has never been published or fully analyzed by scholars in print. It offers valuable insight into the production of West Indian history at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it shows how colonial planters confronted the challenges of their day by attempting to wrest the practice of writing West Indian history from their critics in Great Britain. Unlike these metropolitan writers, Edwards had lived in the West Indian colonies for many years. He positioned his personal experience as being a primary source of his historical legitimacy. Keywords Bryan Edwards – West Indian history – eighteenth century – slavery – abolition Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies is a text well known to scholars of the Caribbean (Edwards 1793). First published in June of 1793, the text was “among the most widely read and influential accounts of the British Caribbean for generations” (V. -

Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin Mcdonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz

‘A Man of Courage and Activity’: Thomas Tew and Pirate Settlements of the Indo - Atlantic Trade World, 1645 -1730 1 Kevin McDonald Department of History University of California, Santa Cruz “The sea is everything it is said to be: it provides unity, transport , the means of exchange and intercourse, if man is prepared to make an effort and pay a price.” – Fernand Braudel In the summer of 1694, Thomas Tew, an infamous Anglo -American pirate, was observed riding comfortably in the open coach of New York’s only six -horse carriage with Benjamin Fletcher, the colonel -governor of the colony. 2 Throughout the far -flung English empire, especially during the seventeenth century, associations between colonial administrators and pirates were de rig ueur, and in this regard , New York was similar to many of her sister colonies. In the developing Atlantic world, pirates were often commissioned as privateers and functioned both as a first line of defense against seaborne attack from imperial foes and as essential economic contributors in the oft -depressed colonies. In the latter half of the seventeenth century, moreover, colonial pirates and privateers became important transcultural brokers in the Indian Ocean region, spanning the globe to form an Indo-Atlantic trade network be tween North America and Madagascar. More than mere “pirates,” as they have traditionally been designated, these were early modern transcultural frontiersmen: in the process of shifting their theater of operations from the Caribbean to the rich trading grounds of the Indian Ocean world, 1 An earlier version of this paper was presented at the “Counter -Currents and Mainstreams in World History” conference at UCLA on December 6-7, 2003, organized by Richard von Glahn for the World History Workshop, a University of California Multi -Campus Research Unit. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

The 20 February 2010 Madeira Flash-Floods

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 12, 715–730, 2012 www.nat-hazards-earth-syst-sci.net/12/715/2012/ Natural Hazards doi:10.5194/nhess-12-715-2012 and Earth © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. System Sciences The 20 February 2010 Madeira flash-floods: synoptic analysis and extreme rainfall assessment M. Fragoso1, R. M. Trigo2, J. G. Pinto3, S. Lopes1,4, A. Lopes1, S. Ulbrich3, and C. Magro4 1IGOT, University of Lisbon, Portugal 2IDL, Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Portugal 3Institute for Geophysics and Meteorology, University of Cologne, Germany 4Laboratorio´ Regional de Engenharia Civil, R.A. Madeira, Portugal Correspondence to: M. Fragoso ([email protected]) Received: 9 May 2011 – Revised: 26 September 2011 – Accepted: 31 January 2012 – Published: 23 March 2012 Abstract. This study aims to characterise the rainfall ex- island of Madeira is quite densely populated, particularly in ceptionality and the meteorological context of the 20 Febru- its southern coast, with circa 267 000 inhabitants in 2011 ary 2010 flash-floods in Madeira (Portugal). Daily and census, with 150 000 (approximately 40 %) living in the Fun- hourly precipitation records from the available rain-gauge chal district, one of the earliest tourism hot spots in Europe, station networks are evaluated in order to reconstitute the currently with approximately 30 000 hotel beds. In 2009, the temporal evolution of the rainstorm, as its geographic inci- archipelago received 1 million guests; this corresponds to an dence, contributing to understand the flash-flood dynamics income of more than 255 Million Euro (INE-Instituto Na- and the type and spatial distribution of the associated im- cional de Estat´ıstica, http://www.ine.pt). -

Redescription of Hypoatherina Valenciennei and Its Relationships to Other Species of Atherinidae in the Pacific and Indian Oceans

Japanese Journal of Ichthyology 魚 類 学 雑 誌 Vol. 35, No. 2 1988 35 巻 2 号 1988年 Redescription of Hypoatherina valenciennei and its Relationships to Other Species of Atherinidae in the Pacific and Indian Oceans Walter Ivantsoff and Maurice Kottelat (Received December 23, 1986) Abstract A review of Tirant's collections and examination of types has resulted in the reidentifica- tion of Haplocheilus argyrotaenia Tirant as Hypoatherina valenciennei (Bleeker) which is found throughout the southwestern Pacific and as far north as Japan. The taxonomic status of H. valenciennei is clarified and Bleeker's emendation of the original specific epithet valenciennei to valenciennesi is rejected. The systematic position of this species is difficult to determine since H. valenciennei shows affinities with both Hypoatherina and Atherinomorus. In the light of the present knowledge, Bleeker's species appears to have greater affinities with Hypoatherina and is therefore placed in this genus. Recent reexamination of the types of Haplo- 1983). The genus Hypoatherina as defined by cheilus argyrotaenia Tirant, 1883, (unaccepted and Ivantsoff (1978) includes all those species with misspelt emendation of Haplochilus Agassiz, 1846, moderately long dorsal process of premaxilla but for Aplocheilus McClelland, 1839) has prompted not longer than eye diameter, lateral process of us to review the status of Hypoatherina valenciennei premaxilla short and broad, lower jaw coronoid (Bleeker, 1853a) which is considered to be the process highly elevated, distinct notch (sensory senior synonym of Tirant's species (thought by canal opening) in posterior margin of anterior him to be an aplocheilid). Although the systema- bony edge of preopercle near its lower corner, tic position of the Pacific atherinids is yet to be body slender and subcylindrical, midlateral band resolved, work to that end has already begun. -

Book Reviews -Robert L

Book Reviews -Robert L. Paquette, David Barry Gaspar, Bondmen and rebels: a study of master-slave relations in Antigua with implications for colonial British America. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, Johns Hopkins Series in Atlantic History, Culture and Society, 1985. xx + 338 pp. -John Johnson, Latin American Politics: A historical bibliography, Clio Bibliography Series No. 16 (ABC Clio Information Services, Santa Barbara, 1984). -John Johnson, Columbus Memorial Library, Travel accounts and descriptions of Latin American and the Caribbean, 1800-1920: A selected bibliography (Organization of American States, Washington D.C. 1982). -Susan Willis, Aart G. Broek, Something rich like chocolate. Aart G. Broek, (Editorial Kooperativo Antiyano Kolibri', Curacao) 1985. -Robert A. Myers, C.J.M.R. Gullick, Myths of a minority: the changing traditions of the Vincentian Caribs. Assen: Van Gorcum, Series: Studies of developing countries, no. 30, 1985. vi + 211 pp. -Jay. R. Mandle, Paget Henry, Peripheral capitalism and underdevelopment in Antigua. New Brunswick and Oxford: Transaction Books, 1985. 274 pp. -Hilary McD. Beckles, Gary Puckrein, Little England: Plantation society and Anglo-Barbadian politics, 1627-1700. New York and London: New York University Press, 1984. xxiv + 235 pp. In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 60 (1986), no: 3/4, Leiden, 239-255 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 10:43:05PM via free access BOOK REVIEWS Bondmen and rebels: a study of master-slave relations in Antigua with implications for colonial British America. DAVID BARRY GASPAR. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, Johns Hopkins Series in Atlantic History, Culture and Society, 1985. -

The University of Chicago the Creole Archipelago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CREOLE ARCHIPELAGO: COLONIZATION, EXPERIMENTATION, AND COMMUNITY IN THE SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN, C. 1700-1796 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TESSA MURPHY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2016 Table of Contents List of Tables …iii List of Maps …iv Dissertation Abstract …v Acknowledgements …x PART I Introduction …1 1. Creating the Creole Archipelago: The Settlement of the Southern Caribbean, 1650-1760...20 PART II 2. Colonizing the Caribbean Frontier, 1763-1773 …71 3. Accommodating Local Knowledge: Experimentations and Concessions in the Southern Caribbean …115 4. Recreating the Creole Archipelago …164 PART III 5. The American Revolution and the Resurgence of the Creole Archipelago, 1774-1785 …210 6. The French Revolution and the Demise of the Creole Archipelago …251 Epilogue …290 Appendix A: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of Dominica …301 Appendix B: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of St. Vincent …310 A Note on Sources …316 Bibliography …319 ii List of Tables 1.1: Respective Populations of France’s Windward Island Colonies, 1671 & 1700 …32 1.2: Respective Populations of Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent c.1730 …39 1.3: Change in Reported Population of Free People of Color in Martinique, 1732-1733 …46 1.4: Increase in Reported Populations of Dominica & St. Lucia, 1730-1745 …50 1.5: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in the Lesser Antilles, 1626-1762 …57 1.6: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in Jamaica & Saint-Domingue, 1526-1762 …58 2.1: Reported Populations of the Ceded Islands c. -

The Spiritual Landscapes of Barbados

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2016 Sacred Grounds and Profane Plantations: The Spiritual Landscapes of Barbados Myles Sullivan College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the African History Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Cultural History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Sullivan, Myles, "Sacred Grounds and Profane Plantations: The Spiritual Landscapes of Barbados" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 945. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/945 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sullivan 1 Sacred Grounds and Profane Plantations: The Spiritual Landscapes of Barbados Myles Sullivan Sullivan 2 Table of Contents Introduction page 3 Background page 4 Research page 6 Spiritual Landscapes page 9 The Archaeology and Anthropology of Spiritual Practices in the Caribbean page 16 Early Spiritual Landscapes page 21 Barbadian Spiritual Landscapes: Liminal Spaces in a “Creole” Slave Society page 33 Spiritual Landscapes of Recent Memory page 47 Works Cited page 52 Figures Fig 1: Map of Barbados page 4 Fig 2: Worker’s Village Site at Saint Nicholas Abbey page 7 Fig 3: Stone pile on ridgeline page 8 Fig 4: Disembarked Africans on Barbados (1625-1850) page 23 Fig 5: Total percentage arrivals of Africans by regions page 23 Fig 6: “Gaming” Pieces from the slave village site page 42 Fig 7: Gully areas at St. -

Reading the Remains of the 17Th Century

AnthroNotes Volume 28 No. 1 Spring 2007 WRITTEN IN BONE READING THE REMAINS OF THE 17TH CENTURY by Kari Bruwelheide and Douglas Owsley ˜ ˜ ˜ [Editor’s Note: The Smithsonian’s Department of Anthro- who came to America, many willingly and others under pology has had a long history of involvement in forensic duress, whose anonymous lives helped shaped the course anthropology by assisting law enforcement agencies in the of our country. retrieval, evaluation, and analysis of human remains for As we commemorate the 400th anniversary of the identification purposes. This article describes how settlement of Jamestown, it is clear that historians and ar- Smithsonian physical anthropologists are applying this same chaeologists have made much progress in piecing together forensic analysis to historic cases, in particular seventeenth the literary records and artifactual evidence that remain from century remains found in Maryland and Virginia, which the early colonial period. Over the past two decades, his- will be the focus of an upcoming exhibition, Written in Bone: torical archaeology especially has had tremendous success Forensic Files of the 17th Century, scheduled to open at the in charting the development of early colonial settlements Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History in No- through careful excavations that have recovered a wealth vember 2008. This exhibition will cover the basics of hu- of 17th century artifacts, materials once discarded or lost, man anatomy and forensic investigation, extending these and until recently buried beneath the soil (Kelso 2006). Such techniques to the remains of colonists teetering on the edge discoveries are informing us about daily life, activities, trade of survival at Jamestown, Virginia, and to the wealthy and relations here and abroad, architectural and defensive strat- well-established individuals of St. -

Medieval Or Early Modern

Medieval or Early Modern Medieval or Early Modern The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton Medieval or Early Modern: The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Ronald Hutton and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7451-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7451-9 CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Ronald Hutton Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 From Medieval to Early Modern: The British Isles in Transition? Steven G. Ellis Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 29 The British Isles in Transition: A View from the Other Side Ronald Hutton Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 42 1492 Revisited Evan T. Jones Chapter Five .............................................................................................