Civil War Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bent's Fort Chapter Santa Fe Trail Association

Bent’s Fort Chapter Santa Fe Trail Association December 2013 Newsletter Membership News from Kathy Wootten DON’T I will start this report with the numbers I am sure FORGET just because they are so impressive. Our that we These total number of memberships is 166 as will con- Future of November 20, 2013. We gained 32 tinue our Events new members and lost only 14 members progress from last year. And remember...the ma- as the jority of memberships are for a family of new year at least two people. ap- December 6: Bent’s proaches Old Fort Christmas and you begin to send your renewal Celebration membership dues in. There will be no January 2014: BFC changes in dues fees or in the process 2014 Annual Meeting, for mailing in your payments. Please Time and Place TBA September 2014: note the membership form on the last Santa Fe Trail Center page of this newsletter. Rendezvous, Larned, A request—please make this the year Kansas that you join the national Santa Fe Trail September 2015: Fur Association or make sure that you renew Trade Symposium THANKS TO ALL who have done what your membership in SFTA. Support from Bent’s Old Fort it takes to attract new people to our all members who care about maintaining September 2015: group—be it manning booths at area our Santa Fe Trail is needed. The form SFTA Symposium, functions, for sending your dues to SFTA is in- Santa Fe, NM inviting cluded in this newsletter. friends to We look forward to getting acquainted come with Inside this issue… with you new members as we look for- you to a ward to 2014. -

American Bronze Co., Chicago

/American j^ronze C^- 41 Vai| pUreii S^ree^, - cHICAGO, ILLS- Co.i Detroit. ite arid <r\ntique t^ponze JVlonumer|tal Wopk.. Salesroom: ART FOUNDRY. II CHICAGO. H. N. HIBBARD, Pres't. PAUL CORNELL, Vice-Pres't, JAS, STEWART, Treas, R J, HAIGHT, Sec'y, THE HEMRT FRAXCIS du POJ^ WIXrERTHUR MUSEUM LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/whiteantiquebronOOamer Tillr rr|ore prominent cemeteries in this country are noW arranged or) what is l<;noWn as the LfavVn I'lan, which gives the grounds a park-like appearaqce, n]ore in harmony With the impulse of our natures to make tl^ese lastresting places beautiful; in striking contrast to the gloomy burying places of olden times. pences, hedges, curbiqg aqd enclosures of all kinds are prol]ibited and tl^e money formerly expended for such fittings is invested in a central monu- ment, theicby enabling the lot oWner to purchase a better niemorial tl]an could otherwise haVe been afforded. (Corner posts are barely Visible aboVe the surface of the ground, and markers at the head of graVes are allowed ' only a feW inches higher, thus preserving the beautiful landscape effect. JViaiiy of tl]e n"ionum|ents novV being erected, and several that are illustrated in this pamphlet, bear feW, if aiw, fcmiily records, thus illustrating the growing desire to provide a fan]ily resting place and an enduring n-jonu- rqent. Without deferring it until there Fjos been a death in the family, as has been the custom in tlie past. -

Custom Report for Wilhelm F Kriesel

Custom Report for Wilhelm F Kriesel ( Per her death cert, she is to be buried at Roselawn ) Name: Marie Grace 'Bessie' Wilkey Burial: 1940 in McAllen, Hidalgo, Texas, USA; ( Per her death cert, she is to be buried at Roselawn ) AB-Grimshaw - Grimshaw Women's Institute Cemetery Name: Joseph Funk Burial: 1975 in Grimshaw, Peace, Alberta, Canada; AB-Grimshaw - Grimshaw Women's Institute Cemetery AL-Grand Bay - Grand Bay Cemetery Name: Dalores Elaine Johnson Burial: 1995 in Grand Bay, Mobile, Alabama, USA; AL-Grand Bay - Grand Bay Cemetery Name: Houndle Lavalle Lindsey Burial: 1982 in Grand Bay, Mobile, Alabama, USA; AL-Grand Bay - Grand Bay Cemetery AZ.National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona - Sec 53 Site 345 Name: Charles Francis Perry Burial: 2007 in Phoenix, Maricopa, Arizona, USA; AZ.National Memorial Cemetery of Arizona - Sec 53 Site 345 AZ-Buckeye - Louis B Hazelton Memorial Cemetery Name: Robert Lyle Reed Burial: 2009 in Buckeye, Maricopa, Arizona, USA; AZ-Buckeye - Louis B Hazelton Memorial Cemetery AZ-Show Low - Show Low Cemetery Name: Archie Leland Prust Burial: 2006 in Show Low, Navajo, Arizona, USA; AZ-Show Low - Show Low Cemetery AZ-Sun City - Sunland Memorial Park Name: George E Lehman Burial: 2000 in Sun City, Maricopa, Arizona, USA; AZ-Sun City - Sunland Memorial Park Name: Ruth Edna Roerig Burial: 1993 in Sun City, Maricopa, Arizona, USA; AZ-Sun City - Sunland Memorial Park AZ-Tucson - East Lawn Palms Cemetery and Mortuary Name: Inez Brown Burial: 2014 in Tucson, Pima, Arizona, USA; AZ-Tucson - East Lawn Palms Cemetery and -

The Civil War & the Northern Plains: a Sesquicentennial Observance

Papers of the Forty-Third Annual DAKOTA CONFERENCE A National Conference on the Northern Plains “The Civil War & The Northern Plains: A Sesquicentennial Observance” Augustana College Sioux Falls, South Dakota April 29-30, 2011 Complied by Kristi Thomas and Harry F. Thompson Major funding for the Forty-Third Annual Dakota Conference was provided by Loren and Mavis Amundson CWS Endowment/SFACF, Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission, Tony and Anne Haga, Carol Rae Hansen, Andrew Gilmour and Grace Hansen-Gilmour, Carol M. Mashek, Elaine Nelson McIntosh, Mellon Fund Committee of Augustana College, Rex Myers and Susan Richards, Rollyn H. Samp in Honor of Ardyce Samp, Roger and Shirley Schuller in Honor of Matthew Schuller, Jerry and Gail Simmons, Robert and Sharon Steensma, Blair and Linda Tremere, Richard and Michelle Van Demark, Jamie and Penny Volin, and the Center for Western Studies. The Center for Western Studies Augustana College 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................................................................... v Anderberg, Kat Sailing Across a Sea of Grass: Ecological Restoration and Conservation on the Great Plains ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Anderson, Grant Sons of Dixie Defend Dakota .......................................................................................................... 13 Benson, Bob The -

Lonely Sentinel

Lonely Sentinel Fort Aubrey and the Defense of the Kansas Frontier, 1864-1866 Defending the Fort: Indians attack a U.S. Cavalry post in the 1870s (colour litho), Schreyvogel, Charles (1861-1912) / Private Collection / Peter Newark Military Pictures / Bridgeman Images Darren L. Ivey History 533: Lost Kansas Communities Chapman Center for Rural Studies Kansas State University Dr. M. J. Morgan Fall 2015 This study examines Fort Aubrey, a Civil War-era frontier post in Syracuse Township, Hamilton County, and the men who served there. The findings are based upon government and archival documents, newspaper and magazine articles, personal reminiscences, and numerous survey works written on the subjects of the United States Army and the American frontier. Map of Kansas featuring towns, forts, trails, and landmarks. SOURCE: Kansas Historical Society. Note: This 1939 map was created by George Allen Root and later reproduced by the Kansas Turnpike Authority. The original drawing was compiled by Root and delineated by W. M. Hutchinson using information provided by the Kansas Historical Society. Introduction By the summer of 1864, Americans had been killing each other on an epic scale for three years. As the country tore itself apart in a “great civil war,” momentous battles were being waged at Mansfield, Atlanta, Cold Harbor, and a host of other locations. These killing grounds would become etched in history for their tales of bravery and sacrifice, but, in the West, there were only sporadic clashes between Federal and Confederate forces. Encounters at Valverde in New Mexico Territory, Mine Creek in Linn County, Kansas, and Sabine Pass in Texas were the exception rather than the norm. -

Printed U.S.A./November 1984 a Contemporary View of the Old Chicago Water Tower District

J,, I •CITY OF CHICAGO Harold Washington, Mayor COMMISSION ON CHICAGO HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL LANDMARKS Ira]. Bach, Chairman Ruth Moore Garbe, Vice-Chairman Joseph Benson, Secretary John W. Baird Jerome R. Butler, Jr. William M. Drake John A. Holabird Elizabeth L. Hollander Irving J. Markin William M. McLenahan, Director Room 516 320 N. Clark Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 (312) 744-3200 Printed U.S.A./November 1984 A contemporary view of the Old Chicago Water Tower District. (Bob Thall, photographer) OLD CHICAGO WATER TOWER DISTRICT Bounded by Chicago Avenue, Seneca and Pearson streets, and Michigan Avenue. The district is com prised of the Old Chicago Water Tower, Chicago Avenue Pumping Station, Fire Station of Engine Company No. 98, Seneca and Water Tower parks. The district was designated a Chicago Landmark by the City Council on October 6, 1971; the district was expanded by the City Council on June 10, 1981. Standing on both north corners of the prominent inter section of Michigan and Chicago avenues are two important and historic links with the past, the Old Chicago Water Tower and the Chicago Avenue Pumping Station. The Old Water Tower, on the northwest corner, has long been recog nized as Chicago's most familiar and beloved landmark. The more architecturally interesting of the two structures, it is no longer functional and has not been since early in this century. The Pumping Station, the still functioning unit of the old waterworks, stands on the northeast corner. When the waterworks were constructed at this site in the late 1860s, there was no busy Michigan Avenue separating the adjoining picturesque buildings. -

Surname First JMA# Death Date Death Location Burial Location Photo

Surname First JMA# Death date Death location Burial Location Photo (MNU) Emily R45511 December 31, 1963 California? Los Molinos Cemetery, Los Molinos, Tehama County, California (MNU) Helen Louise M515211 April 24, 1969 Elmira, Chemung County, New York Woodlawn National Cemetery, Elmira, Chemung County, New York (MNU) Lillian Rose M51785 May 7, 2002 Las Vegas, Clark County, Nevada Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery, Boulder City, Nevada (MNU) Lois L S3.10.211 July 11, 1962 Alhambra, Los Angeles County, California Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, Los Angeles County, California Ackerman Seymour Fred 51733 November 3, 1988 Whiting, Ocean County, New Jersey Cedar Lawn Cemetery, Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Ackerman Abraham L M5173 October 6, 1937 Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Cedar Lawn Cemetery, Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey Ackley Alida M5136 November 5, 1907 Newport, Herkimer County, New York Newport Cemetery, Herkimer, Herkimer County, New York Adrian Rosa Louise M732 December 29, 1944 Los Angeles County, California Fairview Cemetery, Salida, Chaffee County, Colorado Alden Ann Eliza M3.11.1 June 9, 1925 Chicago, Cook County, Illinois Rose Hill Cemetery, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois Alexander Bernice E M7764 November 5, 1993 Whitehall, Pennsylvania Walton Town and Village Cemetery, Walton, Delaware County, New York Allaben Charles Moore 55321 April 12, 1963 Binghamton, Broome County, New York Vestal Hills Memorial Park, Vestal, Broome County, New York Yes Allaben Charles Smith 5532 December 12, 1917 Margaretville, -

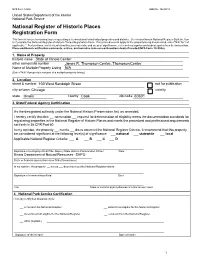

Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" If Property Is Not Part of a Multiple Property Listing)

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name State of Illinois Center other names/site number James R. Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 100 West Randolph Street not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Department of Natural Resources - SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

The Dakota Sioux Indian Wars of 1862-1863

A BGES Civil War Field University Program: Lincoln’s Other War; The Dakota Sioux Indian Wars of 1862-1863 The Indian problem preceded the Civil War and it occupied a good portion of the prewar army’s focus. Men like Richard Ewell and John Bell Hood had extensive prewar experience indeed Hood’s arm had been pinned to his side by an arrow during an early assignment. The war though had eclipsed the peacetime focus on controlling the Indians many of which had been pacified by relocation to reservations. Here men whose life had been nomadic and self reliant were changed in disastrous ways that changed the basic composition of their lives. As the Civil War consumed more and more resources and manpower, tribal treaties administered by Indian Agents were loosely adhered to and in cases ignored. For people whom had become dependent upon government subsidies, to pay traders and other merchants, walks to the agency for the distribution of cash and supplies was both demeaning and crucial especially as the seasons changed. In August 1862 emotions boiled over and when Indians showed up for the handouts and came back empty handed the frustration manifested itself in attacks against settlers who lived in close proximity to the reservation. Indians, under the general control of Little Crow, murdered settlers—most of Scandinavian origin in cold blood and others who mixed with the settlers reacted in different ways—some joined the murderous rampage and others helped warn the ignorant farmers and saved their lives. Still in just over a week, approximately 500 civilians were slaughtered and many mutilated. -

The Knapsack Raleigh Civil War Round Table the Same Rain Falls on Both Friend and Foe

The Knapsack Raleigh Civil War Round Table The same rain falls on both friend and foe. January 7, 2017 Volume 17 Our 191st Meeting Number 1 http://www.raleighcwrt.org January 7 Event Features Ed Bearss Speaking on Battlefield Medicine Edwin C. Bearss is one of the most respected Civil War scholars alive today and is considered by many IMPORTANT NOTICE! to be a national treasure. Due to gubernatorial inaugural events, our Ed served as Chief Historian of annual Ed Bearss event will be held at an the National Park Service and alternative location, Holy Trinity Church in was featured in Ken Burns’ Raleigh. The church is on 100 East Peace PBS series, The Civil War, as Street, just a few blocks north of our usual well as Arts & Entertainment meeting place. The event is $10 per person Channel’s Civil War Journal. and will be held on a Saturday at 2 p.m., with He is an award-winning author, doors opening a half hour earlier. having written or edited more than 20 books in addition to more than 100 articles. Among his many works are The Battle at Wilson’s Creek, Forrest at Brice’s ~ Civil War Medicine ~ Cross Roads, Hardluck Ironclad, and The Vicksburg Campaign. Ed also provides the overview in the Both North and South were medically unprepared RCWRT’s documentary film on the 1865 events in for the battle casualties and exposure to elements North Carolina. and disease that their soldiers would face. Twice as In 1983, Ed received the Department of Interior’s many soldiers would die of disease during the Civil Distinguished Service Award, its highest honor. -

O'neil 1 Soldiers of Both Blue and Grey: the Story and Motivations Of

O’Neil 1 Soldiers of Both Blue and Grey: The Story and Motivations of the Galvanized Yankees There are many well-remembered aspects of the Civil War. The battles of Bull Run, Antietam, and Gettysburg, the burning of Atlanta, or even President Lincoln’s assassination are all events memorialized in textbooks and monuments. Inevitably, however, many stories and figures disappear and are forgotten. One such group are the “Galvanized Yankees.” The term Galvanized Yankees refers to captured Confederate soldiers who, rather than endure the horrors of the overcrowded, undersupplied prisoner of war (POW) camps, would enlist in the Union army to be deployed against the Plains Indians in the West. The Galvanized Yankees came from diverse backgrounds: new immigrants caught in the tide of war, men from the border states with little loyalty to slavery, and men from the Deep South desperate to return home. Why did the Union permit Confederate prisoners to join their ranks? What were the experiences of the Galvanized Yankees? What was their motivation for changing sides, and what impact did they have? In the Autumn of 1862, news began to spread east that the Sioux Indian nations had begun attacking and inflicting numerous atrocities on the American settlers of the Minnesota and Dakota territories. Terrified settlers demanded that the government act, but with the Civil War in full force, the Union was hard pressed to find troops to send. There did exist one great pool of reserves from which to draw troops: Prisoner of War camps. POW camps in the North and the South were overflowing following the breakdown of exchanges in mid 1863. -

Illinois Military Museums & Veterans Memorials

ILLINOIS enjoyillinois.com i It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far nobly advanced. Abraham Lincoln Illinois State Veterans Memorials are located in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield. The Middle East Conflicts Wall Memorial is situated along the Illinois River in Marseilles. Images (clockwise from top left): World War II Illinois Veterans Memorial, Illinois Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Vietnam Veterans Annual Vigil), World War I Illinois Veterans Memorial, Lincoln Tomb State Historic Site (Illinois Department of Natural Resources), Illinois Korean War Memorial, Middle East Conflicts Wall Memorial, Lincoln Tomb State Historic Site (Illinois Office of Tourism), Illinois Purple Heart Memorial Every effort was made to ensure the accuracy of information in this guide. Please call ahead to verify or visit enjoyillinois.com for the most up-to-date information. This project was partially funded by a grant from the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity/Office of Tourism. 12/2019 10,000 What’s Inside 2 Honoring Veterans Annual events for veterans and for celebrating veterans Honor Flight Network 3 Connecting veterans with their memorials 4 Historic Forts Experience history up close at recreated forts and historic sites 6 Remembering the Fallen National and state cemeteries provide solemn places for reflection is proud to be home to more than 725,000 8 Veterans Memorials veterans and three active military bases. Cities and towns across the state honor Illinois We are forever indebted to Illinois’ service members and their veterans through memorials, monuments, and equipment displays families for their courage and sacrifice.