The Business of Congress After September 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peoria Unified School District 6-Day Rotation Schedule

Peoria Unified School District 2020 – 2021 School Year Six-Day Rotation Schedule August 2020 January 2021 Day 1: August 17, 19 AM, 26 PM and 27 Day 1: January 6 PM, 11 and 22 Day 2: August 18 and 28 Day 2: January 12, 13 AM, 20 PM and 25 Day 3: August 23 and 31 Day 3: January 4, 14, 26 and 27 AM Day 4: August 21 Day 4: January 5, 15 and 28 Day 5: August 24 Day 5: January 7, 19 and 29 Day 6: August 25 Day 6: January 8 and 21 September 2020 February 2021 Day 1: September 8, 18 and 29 Day 1: February 2, 12 and 25 Day 2: September 2 AM, 9 PM, and 21 Day 2: February 4, 16 and 26 Day 3: September 11, 16 AM and 23 PM Day 3: February 3 PM, 5 and 18 Day 4: September 1, 14, 24 and 30 AM Day 4: February 8, 10 AM, 17 PM and 19 Day 5: September 3, 15 and 25 Day 5: February 9, 22 and 24 AM Day 6: September 4, 17 and 28 Day 6: February 1, 11 and 23 October 2020 March 2021 Day 1: October 9 and 22 Day 1: March 8, 25 and 31 AM Day 2: October 1, 13 and 23 Day 2: March 9 and 26 Day 3: October 2, 15 and 26 Day 3: March 1, 11 and 29 Day 4: October 5, 7 PM, 16 and 27 Day 4: March 2, 12 and 30 Day 5: October 6, 14 AM, 21 PM and 29 Day 5: March 3 PM, 4 and 22 Day 6: October 8, 20, 28 AM and 30 Day 6: March 5, 10 AM, 23 and 24 PM November 2020 April 2021 Day 1: November 2, 12 and 20 Day 1: April 5, 7 PM, 15 and 27 Day 2: November 3, 13 and 30 Day 2: April 6, 14 AM, 16, 21 PM and 29 Day 3: November 5 and 16 Day 3: April 8, 19, 28 AM and 30 Day 4: November 6 and 17 Day 4: April 9 and 20 Day 5: November 9 and 18 Day 5: April 1, 12 and 22 Day 6: November 4 PM, 10 and 19 Day 6: April 2, 13 and 26 December 2020 May 2021 Day 1: December 7, 15 and 16 AM Day 1: May 7 and 18 Day 2: December 8 and 17 Day 2: May 10 and 19 Day 3: December 1 and 9 Day 3: May 5 PM, 11 and 20 Day 4: December 2 and 10 Day 4: May 3, 12 AM, 13 Day 5: December 3 and 11 Day 5: May 4 and 14 Day 6: December 4 and 14 Day 6: May 6 and 17 EARLY RELEASE or MODIFIED WEDNESDAY • Elementary schools starting at 8 a.m. -

U.S. Coast Guard at Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941

U.S. COAST GUARD UNITS IN HAWAII December 7, 1941 Coast Guard vessels in service in Hawaii were the 327-foot cutter Taney, the 190-foot buoy tender Kukui, two 125- foot patrol craft: Reliance and Tiger, two 78-foot patrol boats and several smaller craft. At the time of the attack, Taney was tied up at Pier Six in Honolulu Harbor, Reliance and the unarmed Kukui both lay at Pier Four and Tiger was on patrol along the western shore of Oahu. All were performing the normal duties for a peacetime Sunday. USCGC Taney (WPG-37); Commanding Officer: Commander Louis B. Olson, USCG. Taney was homeported in Honolulu; 327-foot Secretary Class cutter; Commissioned in 1936; Armament: two 5-inch/51; four 3-inch/ 50s and .50 caliber machine guns. The 327-foot cutter Taney began working out of Honolulu in as soon as she was commissioned. On the morning of 7 December 1941, she was tied up at pier six in Honolulu Harbor six miles away from the naval anchorage. After the first Japanese craft appeared over the island, Taney's crew went to general quarters and made preparations to get underway. While observing the attack over Pearl Harbor, Taney received no orders to move and did not participate in the initial attack by the Japanese. Just after 09:00, when the second wave of planes began their attack on the naval anchorage, Taney fired on high altitude enemy aircraft with her 3-inch guns and .50 caliber machine guns. The extreme range of the planes limited the effect of the fire and the guns were secured after twenty minutes. -

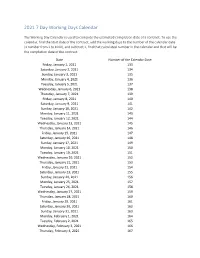

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

December 7, 2020, 7:00 P.M

Eau Claire School Board Minutes Monday, December 7, 2020, 7:00 p.m. Webex Virtual Meeting Generated by Meta Miske Members present Lori Bica, Joshua Clements, Aaron Harder, Phil Lyons, Tim Nordin, Marquell Johnson, Erica Zerr CALL TO ORDER President Nordin called the meeting to order at 6:00 p.m. Board Secretary Meta Miske confirmed the meeting had been properly noticed and was in compliance with the Open Meeting Law. A roll call was conducted to verify quorum. Motion by Marquell Johnson, second by Lori Bica, to move to Closed Session pursuant to 19.85(1)(e);Deliberating or negotiating the purchasing of public properties, the investing of public funds, or conducting other specified public business, whenever competitive or bargaining reasons require a closed session for the purpose of discussing legal services. Motion carried Yes: Lori Bica, Joshua Clements, Aaron Harder, Phil Lyons, Tim Nordin, Marquell Johnson, Erica Zerr OPEN SESSION The Board reconvened in open session at 7:02 p.m. The Pledge of Allegiance was offered. PUBLIC FORUM The following members of the public addressed the Board: Jessica Borst, Mark Goings. BOARD/ADMINISTRATIVE REPORTS Superintendent's Report Superintendent Johnson gave a report on the transition to 100% Virtual and decision to return to blended learning on December 10. Board President's Report President Nordin gave an update on the Board’s work with Coherent Governance. STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE REPORT Emery Thul gave a report for Memorial High School. Zoe Wolfe gave a report for North High School. OTHER REPORTS School Board Committee Reports Budget Development Committee reviewed the Capital Improvement Budget and discussed future work. -

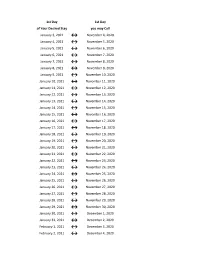

Flex Dates.Xlsx

1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call January 3, 2021 ↔ November 4, 2020 January 4, 2021 ↔ November 5, 2020 January 5, 2021 ↔ November 6, 2020 January 6, 2021 ↔ November 7, 2020 January 7, 2021 ↔ November 8, 2020 January 8, 2021 ↔ November 9, 2020 January 9, 2021 ↔ November 10, 2020 January 10, 2021 ↔ November 11, 2020 January 11, 2021 ↔ November 12, 2020 January 12, 2021 ↔ November 13, 2020 January 13, 2021 ↔ November 14, 2020 January 14, 2021 ↔ November 15, 2020 January 15, 2021 ↔ November 16, 2020 January 16, 2021 ↔ November 17, 2020 January 17, 2021 ↔ November 18, 2020 January 18, 2021 ↔ November 19, 2020 January 19, 2021 ↔ November 20, 2020 January 20, 2021 ↔ November 21, 2020 January 21, 2021 ↔ November 22, 2020 January 22, 2021 ↔ November 23, 2020 January 23, 2021 ↔ November 24, 2020 January 24, 2021 ↔ November 25, 2020 January 25, 2021 ↔ November 26, 2020 January 26, 2021 ↔ November 27, 2020 January 27, 2021 ↔ November 28, 2020 January 28, 2021 ↔ November 29, 2020 January 29, 2021 ↔ November 30, 2020 January 30, 2021 ↔ December 1, 2020 January 31, 2021 ↔ December 2, 2020 February 1, 2021 ↔ December 3, 2020 February 2, 2021 ↔ December 4, 2020 1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call February 3, 2021 ↔ December 5, 2020 February 4, 2021 ↔ December 6, 2020 February 5, 2021 ↔ December 7, 2020 February 6, 2021 ↔ December 8, 2020 February 7, 2021 ↔ December 9, 2020 February 8, 2021 ↔ December 10, 2020 February 9, 2021 ↔ December 11, 2020 February 10, 2021 ↔ December 12, 2020 February 11, 2021 ↔ December 13, 2020 -

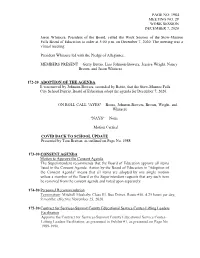

December 7 Work Session

PAGE NO: 1984 MEETING NO. 29 WORK SESSION DECEMBER 7, 2020 Jason Whitacre, President of the Board, called the Work Session of the Stow-Munroe Falls Board of Education to order at 5:00 p.m. on December 7, 2020. The meeting was a virtual meeting. President Whitacre led with the Pledge of Allegiance. MEMBERS PRESENT – Gerry Bettio, Lisa Johnson-Bowers, Jessica Wright, Nancy Brown, and Jason Whitacre 172-20 ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA It was moved by Johnson-Bowers, seconded by Bettio, that the Stow-Munroe Falls City School District Board of Education adopt the agenda for December 7, 2020. ON ROLL CALL "AYES" – Bettio, Johnson-Bowers, Brown, Wright, and Whitacre "NAYS" – None Motion Carried COVID BACK TO SCHOOL UPDATE Presented by Tom Bratten; as outlined on Page No. 1988. 173-20 CONSENT AGENDA Motion to Approve the Consent Agenda The Superintendent recommends that the Board of Education approve all items listed in the Consent Agenda. Action by the Board of Education in "Adoption of the Consent Agenda" means that all items are adopted by one single motion unless a member of the Board or the Superintendent requests that any such item be removed from the consent agenda and voted upon separately. 174-20 Personnel Recommendation Termination: Mitchell Moskaly: Class III, Bus Driver, Route #50, 4.25 hours per day, 9 months; effective November 25, 2020. 175-20 Contract for Services-Summit County Educational Service Center-Lifting Leaders Facilitation Approve the Contract for Services-Summit County Educational Service Center- Lifting Leaders Facilitation; as presented in Exhibit #1, as presented on Page No. -

Framing Pearl Harbor and the 9/11 Attacks

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Summer 2012 Asahi Shimbun and The New York Times: Framing Pearl Harbor and the 9/11 Attacks Maiko Kunii San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Kunii, Maiko, "Asahi Shimbun and The New York Times: Framing Pearl Harbor and the 9/11 Attacks" (2012). Master's Theses. 4197. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.y2gb-agu6 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4197 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASAHI SHIMBUN AND THE NEW YORK TIMES: FRAMING PEARL HARBOR AND THE 9/11 ATTACKS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Maiko Kunii August 2012 © 2012 Maiko Kunii ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ASAHI SHIMBUN AND THE NEW YORK TIMES: FRAMING PEARL HARBOR AND THE 9/11 ATTACKS by Maiko Kunii APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATIONS SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY August 2012 Dr. Diana Stover School of Journalism and Mass Communications Dr. Yoshimitsu Shimazu Department of World Languages & Literature Dr. William Tillinghast School of Journalism and Mass Communications ABSTRACT ASAHI SHIMBUN AND THE NEW YORK TIMES: FRAMING PEARL HARBOR AND THE 9/11 ATTACKS by Maiko Kunii The researcher analyzed visual frames in the photo coverage in the New York Times and the Japanese newspaper, Asahi Shimbun, following the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941 and the 9/11 attacks in 2001. -

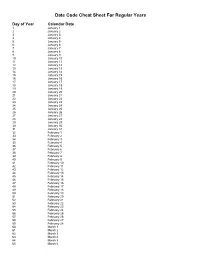

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

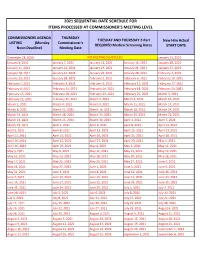

2021 Sequential Date List

2021 SEQUENTIAL DATE SCHEDULE FOR ITEMS PROCESSED AT COMMISSIONER'S MEETING LEVEL COMMISSIONERS AGENDA THURSDAY TUESDAY AND THURSDAY 2-Part New Hire Actual LISTING (Monday Commissioner's REQUIRED Medical Screening Dates START DATE Noon Deadline) Meeting Date December 28, 2020 NO MEETING SCHEDULED January 13, 2021 January 4, 2021 January 7, 2021 January 12, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 20, 2021 January 11, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 19, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 27, 2021 January 18, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 26, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 3, 2021 January 25, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 2, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 10, 2021 February 1, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 9, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 17, 2021 February 8, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 16, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 24, 2021 February 15, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 23, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 3, 2021 February 22, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 2, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 10, 2021 March 1, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 9, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 17, 2021 March 8, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 16, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 24, 2021 March 15, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 23, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 31, 2021 March 22, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 30, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 7, 2021 March 29, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 6, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 14, 2021 April 5, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 13, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 21, 2021 April 12, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 20, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 28, 2021 April 19, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 27, 2021 April -

Pay Date Calendar

Pay Date Information Select the pay period start date that coincides with your first day of employment. Pay Period Pay Period Begins (Sunday) Pay Period Ends (Saturday) Official Pay Date (Thursday)* 1 January 10, 2016 January 23, 2016 February 4, 2016 2 January 24, 2016 February 6, 2016 February 18, 2016 3 February 7, 2016 February 20, 2016 March 3, 2016 4 February 21, 2016 March 5, 2016 March 17, 2016 5 March 6, 2016 March 19, 2016 March 31, 2016 6 March 20, 2016 April 2, 2016 April 14, 2016 7 April 3, 2016 April 16, 2016 April 28, 2016 8 April 17, 2016 April 30, 2016 May 12, 2016 9 May 1, 2016 May 14, 2016 May 26, 2016 10 May 15, 2016 May 28, 2016 June 9, 2016 11 May 29, 2016 June 11, 2016 June 23, 2016 12 June 12, 2016 June 25, 2016 July 7, 2016 13 June 26, 2016 July 9, 2016 July 21, 2016 14 July 10, 2016 July 23, 2016 August 4, 2016 15 July 24, 2016 August 6, 2016 August 18, 2016 16 August 7, 2016 August 20, 2016 September 1, 2016 17 August 21, 2016 September 3, 2016 September 15, 2016 18 September 4, 2016 September 17, 2016 September 29, 2016 19 September 18, 2016 October 1, 2016 October 13, 2016 20 October 2, 2016 October 15, 2016 October 27, 2016 21 October 16, 2016 October 29, 2016 November 10, 2016 22 October 30, 2016 November 12, 2016 November 24, 2016 23 November 13, 2016 November 26, 2016 December 8, 2016 24 November 27, 2016 December 10, 2016 December 22, 2016 25 December 11, 2016 December 24, 2016 January 5, 2017 26 December 25, 2016 January 7, 2017 January 19, 2017 1 January 8, 2017 January 21, 2017 February 2, 2017 2 January -

2016 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2016 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2016 306 Saturday, January 2, 2016 307 Sunday, January 3, 2016 308 Monday, January 4, 2016 309 Tuesday, January 5, 2016 310 Wednesday, January 6, 2016 311 Thursday, January 7, 2016 312 Friday, January 8, 2016 313 Saturday, January 9, 2016 314 Sunday, January 10, 2016 315 Monday, January 11, 2016 316 Tuesday, January 12, 2016 317 Wednesday, January 13, 2016 318 Thursday, January 14, 2016 319 Friday, January 15, 2016 320 Saturday, January 16, 2016 321 Sunday, January 17, 2016 322 Monday, January 18, 2016 323 Tuesday, January 19, 2016 324 Wednesday, January 20, 2016 325 Thursday, January 21, 2016 326 Friday, January 22, 2016 327 Saturday, January 23, 2016 328 Sunday, January 24, 2016 329 Monday, January 25, 2016 330 Tuesday, January 26, 2016 331 Wednesday, January 27, 2016 332 Thursday, January 28, 2016 333 Friday, January 29, 2016 334 Saturday, January 30, 2016 335 Sunday, January 31, 2016 336 Monday, February 1, 2016 337 Tuesday, February 2, 2016 338 Wednesday, February 3, 2016 339 Thursday, February 4, 2016 340 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2016 341 Saturday, February 6, 2016 342 Sunday, February -

The Tenth Anniversary

9/11: The Tenth Anniversary Catastrophes IN THIS ARTICLE INSURANCE INFORMATION INSTITUTE RESOURCES OTHER RESOURCES SHARE THIS DOWNLOAD TO PDF September 11, 2001, like the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, is a day that lives in infamy. But 9/11 was different in the sense that the attacks targeted not only a military site—the Pentagon building in Virginia—but an internationally recognized building which was the workplace for thousands of civilians, New York City’s World Trade Center. Nearly 3,000 people died on 9/11 in Virginia, New York and Pennsylvania as a group of terrorists hijacked four commercial airplanes, and turned them into weapons of mass destruction. The U.S. foreign policy initiatives launched after 9/11 are widely known, and have been extensively chronicled. The changes to U.S. commercial aviation practices, and the formation of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, fall into this category, too. Over the past decade the Insurance Information Institute (I.I.I.) has examined a lesser known impact of that day’s events, namely the broad insurance repercussions. Indeed, the I.I.I.’s white paper on terrorism risk insurance, updated most recently in April 2011, offers an excellent primer on Congress’ enactment of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) in 2002, and how that law has altered the way private sector insurers and reinsurers assess the threat terrorists pose to their policyholders. The death of Osama bin Laden in May 2011 rekindled public and media interest in this topic, as reflected in the first of the two I.I.I.