Framing Pearl Harbor and the 9/11 Attacks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mass Media in Japan, Fake News in the World

Mass Media in Japan, Fake News in the World FORUM REPORT 013 Mass Media in Japan, Fake News in the World Reexamining Japan in Global Context Forum, Tokyo, Japan, April 2, 2018 The Japanese Media in flux: Watchdog or Fake News? Daisuke Nakai Asahi Shimbun* The Japanese media are diverse, vibrant, and trusted by that I use.” This placed Japan 28th out of 36 countries. In the public. In recent years, however, this trust has declined, the Japan Press Research Institute study, only 28.9 percent although it is unclear to what extent. Foreign and domestic answered that newspapers served as a watchdog against the critics, including within the Japanese media, have expressed government, with 42.4 percent thinking that “newspapers do concern, with some claiming that press freedom is in decline. not report on all they know about politicians.” In the MIAC Japanese newspapers have been feeling the effects of the poll, while 73.5% trusted newspapers for politics and eco- Internet, as in other countries. Although circulation and ad- nomics, only 51.2% did so for “the safety of nuclear energy” vertising revenue are down, Japan still enjoys a large media and 56.9% for “diplomatic issues in East Asia.” Various stud- presence. As of April 2017, the Japan Newspaper Publish- ies also show that younger people tend to trust the media ers & Editors Association’s membership consisted of 104 less. newspapers, 4 wire services, and 22 television stations, for a Many critics raise the “Kisha (press) clubs” as a symbol of total of 130 companies. Many other magazines and Internet- both the closed nature of the press and the close relationship based publications do not belong to the Association but are between reporters and the people they cover. -

Peoria Unified School District 6-Day Rotation Schedule

Peoria Unified School District 2020 – 2021 School Year Six-Day Rotation Schedule August 2020 January 2021 Day 1: August 17, 19 AM, 26 PM and 27 Day 1: January 6 PM, 11 and 22 Day 2: August 18 and 28 Day 2: January 12, 13 AM, 20 PM and 25 Day 3: August 23 and 31 Day 3: January 4, 14, 26 and 27 AM Day 4: August 21 Day 4: January 5, 15 and 28 Day 5: August 24 Day 5: January 7, 19 and 29 Day 6: August 25 Day 6: January 8 and 21 September 2020 February 2021 Day 1: September 8, 18 and 29 Day 1: February 2, 12 and 25 Day 2: September 2 AM, 9 PM, and 21 Day 2: February 4, 16 and 26 Day 3: September 11, 16 AM and 23 PM Day 3: February 3 PM, 5 and 18 Day 4: September 1, 14, 24 and 30 AM Day 4: February 8, 10 AM, 17 PM and 19 Day 5: September 3, 15 and 25 Day 5: February 9, 22 and 24 AM Day 6: September 4, 17 and 28 Day 6: February 1, 11 and 23 October 2020 March 2021 Day 1: October 9 and 22 Day 1: March 8, 25 and 31 AM Day 2: October 1, 13 and 23 Day 2: March 9 and 26 Day 3: October 2, 15 and 26 Day 3: March 1, 11 and 29 Day 4: October 5, 7 PM, 16 and 27 Day 4: March 2, 12 and 30 Day 5: October 6, 14 AM, 21 PM and 29 Day 5: March 3 PM, 4 and 22 Day 6: October 8, 20, 28 AM and 30 Day 6: March 5, 10 AM, 23 and 24 PM November 2020 April 2021 Day 1: November 2, 12 and 20 Day 1: April 5, 7 PM, 15 and 27 Day 2: November 3, 13 and 30 Day 2: April 6, 14 AM, 16, 21 PM and 29 Day 3: November 5 and 16 Day 3: April 8, 19, 28 AM and 30 Day 4: November 6 and 17 Day 4: April 9 and 20 Day 5: November 9 and 18 Day 5: April 1, 12 and 22 Day 6: November 4 PM, 10 and 19 Day 6: April 2, 13 and 26 December 2020 May 2021 Day 1: December 7, 15 and 16 AM Day 1: May 7 and 18 Day 2: December 8 and 17 Day 2: May 10 and 19 Day 3: December 1 and 9 Day 3: May 5 PM, 11 and 20 Day 4: December 2 and 10 Day 4: May 3, 12 AM, 13 Day 5: December 3 and 11 Day 5: May 4 and 14 Day 6: December 4 and 14 Day 6: May 6 and 17 EARLY RELEASE or MODIFIED WEDNESDAY • Elementary schools starting at 8 a.m. -

U.S. Coast Guard at Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941

U.S. COAST GUARD UNITS IN HAWAII December 7, 1941 Coast Guard vessels in service in Hawaii were the 327-foot cutter Taney, the 190-foot buoy tender Kukui, two 125- foot patrol craft: Reliance and Tiger, two 78-foot patrol boats and several smaller craft. At the time of the attack, Taney was tied up at Pier Six in Honolulu Harbor, Reliance and the unarmed Kukui both lay at Pier Four and Tiger was on patrol along the western shore of Oahu. All were performing the normal duties for a peacetime Sunday. USCGC Taney (WPG-37); Commanding Officer: Commander Louis B. Olson, USCG. Taney was homeported in Honolulu; 327-foot Secretary Class cutter; Commissioned in 1936; Armament: two 5-inch/51; four 3-inch/ 50s and .50 caliber machine guns. The 327-foot cutter Taney began working out of Honolulu in as soon as she was commissioned. On the morning of 7 December 1941, she was tied up at pier six in Honolulu Harbor six miles away from the naval anchorage. After the first Japanese craft appeared over the island, Taney's crew went to general quarters and made preparations to get underway. While observing the attack over Pearl Harbor, Taney received no orders to move and did not participate in the initial attack by the Japanese. Just after 09:00, when the second wave of planes began their attack on the naval anchorage, Taney fired on high altitude enemy aircraft with her 3-inch guns and .50 caliber machine guns. The extreme range of the planes limited the effect of the fire and the guns were secured after twenty minutes. -

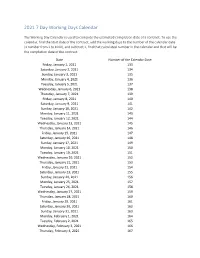

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

THE MIT JAPAN PROGRAM I~~~~~~~~A

THE MIT JAPAN PROGRAM i~~~~~~~~A 0; - -) 'V3 ··it Science, Technology, Management kit 0-~ .Z9 EXPLORING THE INTERSECTION OF GOVERNMENT, POLITICS AND THE NEWS MEDIA IN JAPAN: THE TSUBAKI HA TSUGEN INCIDENT Paul M. Berger MITJP 95-04 Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology --IIICI--l,.-..-.- --------- Exploring the Intersection of Government, Politics and the News Media in Japan The Tsubaki Hatsugen Incident Paul M. Berger MITJP 95-04 Distributed Courtesy of the MIT Japan Program Science Technology * Management Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Room E38-7th Floor Cambridge, MA 02139 phone: 617-253-2839 fax: 617-258-7432 © MIT Japan Program 1_ 9___0_1____ YII_ IX____ __ About the MIT Japan Program and its Working Paper Series The MIT Japan Program was founded in 1981 to create a new generation of technologically sophisticated "Japan-aware" scientists, engineers, and managers in the United States. The Program's corporate sponsors, as well as support from the government and from private foundations, have made it the largest, most comprehensive, and most widely emulated center of applied Japanese studies in the world. The intellectual focus of the Program is to integrate the research methodologies of the social sciences, the humanities, and technology to approach issues confronting the United States and Japan in their relations involving science and technology. The Program is uniquely positioned to make use of MIT's extensive network of Japan-related resources, which include faculty, researchers, and library collections, as well as a Tokyo-based office. Through its three core activities, namely, education, research, and public awareness, the Program disseminates both to its sponsors and to the interested public its expertise on Japanese science and technology and on how that science and technology is managed. -

December 7, 2020, 7:00 P.M

Eau Claire School Board Minutes Monday, December 7, 2020, 7:00 p.m. Webex Virtual Meeting Generated by Meta Miske Members present Lori Bica, Joshua Clements, Aaron Harder, Phil Lyons, Tim Nordin, Marquell Johnson, Erica Zerr CALL TO ORDER President Nordin called the meeting to order at 6:00 p.m. Board Secretary Meta Miske confirmed the meeting had been properly noticed and was in compliance with the Open Meeting Law. A roll call was conducted to verify quorum. Motion by Marquell Johnson, second by Lori Bica, to move to Closed Session pursuant to 19.85(1)(e);Deliberating or negotiating the purchasing of public properties, the investing of public funds, or conducting other specified public business, whenever competitive or bargaining reasons require a closed session for the purpose of discussing legal services. Motion carried Yes: Lori Bica, Joshua Clements, Aaron Harder, Phil Lyons, Tim Nordin, Marquell Johnson, Erica Zerr OPEN SESSION The Board reconvened in open session at 7:02 p.m. The Pledge of Allegiance was offered. PUBLIC FORUM The following members of the public addressed the Board: Jessica Borst, Mark Goings. BOARD/ADMINISTRATIVE REPORTS Superintendent's Report Superintendent Johnson gave a report on the transition to 100% Virtual and decision to return to blended learning on December 10. Board President's Report President Nordin gave an update on the Board’s work with Coherent Governance. STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE REPORT Emery Thul gave a report for Memorial High School. Zoe Wolfe gave a report for North High School. OTHER REPORTS School Board Committee Reports Budget Development Committee reviewed the Capital Improvement Budget and discussed future work. -

IBBY-Asahi Reading Promotion Award 2018, Remarks by Shin-Ichi Kawarada, the Asahi Shimbun, 30 August 2018, Athens, Greece

IBBY-Asahi Reading Promotion Award 2018, remarks by Shin-ichi Kawarada, The Asahi Shimbun, 30 August 2018, Athens, Greece Kalimera sas. I am so glad to join the IBBY international congress in Athens and it is an honor for me to meet everyone at the ceremony of IBBY-Asahi reading promotion award today. I am a chief of the Rome bureau of the Japanese daily newspaper The Asahi Shimbun and I am in charge of the Mediterranean countries including Greece. For your information, the Asahi Shimbun is one of the leading daily broadsheet written in Japanese and we deliver about six million copies to families in Japan every morning. I am a correspondent in Rome and I write articles every day to send to Japan covering every topic, not only politics and economics but also culture and fine arts. However, I’m not good at writing even now. I am very curious to see the parts of the world I’ve never seen. Especially in my childhood, I loved to daydream and spend time in a fictional world as if I were a character in a story. Books transported me to different worlds. I am so grateful to my parents for giving me a lot of illustrated and classic children’s books that every child should read. I present here some books which are so memorable to me and that I can’t forget to this day. One is a Japanese illustrated book “Nenaiko dareda”, it means “Who wouldn’t sleep?” , which my mother often read to me when I was two or three years old. -

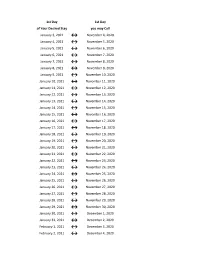

Flex Dates.Xlsx

1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call January 3, 2021 ↔ November 4, 2020 January 4, 2021 ↔ November 5, 2020 January 5, 2021 ↔ November 6, 2020 January 6, 2021 ↔ November 7, 2020 January 7, 2021 ↔ November 8, 2020 January 8, 2021 ↔ November 9, 2020 January 9, 2021 ↔ November 10, 2020 January 10, 2021 ↔ November 11, 2020 January 11, 2021 ↔ November 12, 2020 January 12, 2021 ↔ November 13, 2020 January 13, 2021 ↔ November 14, 2020 January 14, 2021 ↔ November 15, 2020 January 15, 2021 ↔ November 16, 2020 January 16, 2021 ↔ November 17, 2020 January 17, 2021 ↔ November 18, 2020 January 18, 2021 ↔ November 19, 2020 January 19, 2021 ↔ November 20, 2020 January 20, 2021 ↔ November 21, 2020 January 21, 2021 ↔ November 22, 2020 January 22, 2021 ↔ November 23, 2020 January 23, 2021 ↔ November 24, 2020 January 24, 2021 ↔ November 25, 2020 January 25, 2021 ↔ November 26, 2020 January 26, 2021 ↔ November 27, 2020 January 27, 2021 ↔ November 28, 2020 January 28, 2021 ↔ November 29, 2020 January 29, 2021 ↔ November 30, 2020 January 30, 2021 ↔ December 1, 2020 January 31, 2021 ↔ December 2, 2020 February 1, 2021 ↔ December 3, 2020 February 2, 2021 ↔ December 4, 2020 1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call February 3, 2021 ↔ December 5, 2020 February 4, 2021 ↔ December 6, 2020 February 5, 2021 ↔ December 7, 2020 February 6, 2021 ↔ December 8, 2020 February 7, 2021 ↔ December 9, 2020 February 8, 2021 ↔ December 10, 2020 February 9, 2021 ↔ December 11, 2020 February 10, 2021 ↔ December 12, 2020 February 11, 2021 ↔ December 13, 2020 -

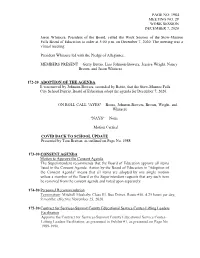

December 7 Work Session

PAGE NO: 1984 MEETING NO. 29 WORK SESSION DECEMBER 7, 2020 Jason Whitacre, President of the Board, called the Work Session of the Stow-Munroe Falls Board of Education to order at 5:00 p.m. on December 7, 2020. The meeting was a virtual meeting. President Whitacre led with the Pledge of Allegiance. MEMBERS PRESENT – Gerry Bettio, Lisa Johnson-Bowers, Jessica Wright, Nancy Brown, and Jason Whitacre 172-20 ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA It was moved by Johnson-Bowers, seconded by Bettio, that the Stow-Munroe Falls City School District Board of Education adopt the agenda for December 7, 2020. ON ROLL CALL "AYES" – Bettio, Johnson-Bowers, Brown, Wright, and Whitacre "NAYS" – None Motion Carried COVID BACK TO SCHOOL UPDATE Presented by Tom Bratten; as outlined on Page No. 1988. 173-20 CONSENT AGENDA Motion to Approve the Consent Agenda The Superintendent recommends that the Board of Education approve all items listed in the Consent Agenda. Action by the Board of Education in "Adoption of the Consent Agenda" means that all items are adopted by one single motion unless a member of the Board or the Superintendent requests that any such item be removed from the consent agenda and voted upon separately. 174-20 Personnel Recommendation Termination: Mitchell Moskaly: Class III, Bus Driver, Route #50, 4.25 hours per day, 9 months; effective November 25, 2020. 175-20 Contract for Services-Summit County Educational Service Center-Lifting Leaders Facilitation Approve the Contract for Services-Summit County Educational Service Center- Lifting Leaders Facilitation; as presented in Exhibit #1, as presented on Page No. -

1 Report (Abridged) the Asahi Shimbun Co. Third-Party

Report (Abridged) The Asahi Shimbun Co. Third-Party Committee December 22, 2014 Chairman: Hideki Nakagome Members: Yukio Okamoto Shinichi Kitaoka Soichiro Tahara Sumio Hatano Kaori Hayashi Masayasu Hosaka 1 1. Background to the Preparation of this Report and Matters for Investigation (1) Background to the preparation of this report This Committee was established by Tadakazu Kimura, president of The Asahi Shimbun Co., and charged by him with the task of investigating and making recommendations regarding coverage of the comfort women issue and other matters by The Asahi Shimbun. (2) Matters for investigation A) Establishing the facts The circumstances under which The Asahi Shimbun produced a total of 16 articles between 1982 and 1997 citing the testimony of Seiji Yoshida that during the Pacific War he had, on Jeju Island (in present South Korea), and acting as the head of the mobilization section at the Shimonoseki Branch of the Yamaguchi Prefectural Romu Hokokukai labor organization, forcibly taken away numerous Korean women for the purpose of compelling them to serve as so-called “comfort women” (hereafter, “the Yoshida testimony”). The circumstances behind the failure of The Asahi Shimbun to retract these articles citing the Yoshida testimony until the publication of the newspaper’s special coverage, Ianfu mondai wo kangaeru (Thinking about the comfort women issue), carried in the August 5, 2014 and August 6, 2014 morning editions of the newspaper. The circumstances behind the production of other major Asahi Shimbun articles on the comfort women issue not involving the Yoshida testimony. The circumstances behind The Asahi Shimbun seeking changes in and temporarily refusing to publish a column by Akira Ikegami scheduled to run in the August 29, 2014 edition. -

Pro-Nazi Newspapers in Showa Wartime Japan, the Increase in Anti-Semitism and Those Who Opposed This Trend

JISMOR 10 Pro-Nazi Newspapers in Showa Wartime Japan, the Increase in Anti-Semitism and Those Who Opposed this Trend Masanori MIYAZAWA Abstract A major turning point for Japan during the wartime Showa era was the Japan-Germany-Italy Anti-Comintern Pact in 1937, which led Japan to join the Axis alliance through the Tripartite Pact signed with Italy and Germany in 1940. Until the mid 1930s, Japanese newspapers were severely critical toward Hitler. Then in 1935, the Asahi Shimbun became the first to switch to a reporting line that expressed approval of Hitler to the point of glorifying his politics. The Asahi Shimbun was soon followed by other newspapers, which were unanimous in welcoming the Tripartite Pact as the beginning of “a new era in the world’s history that is bound to contribute to humanity’s wellbeing” and in sympathizing with Germany in its oppression of Jews. On the other hand, there were liberal activists who were opposed to the anti-Jewish trend and remained critical of Hitler. One of them, Kiyoshi KIYOSAWA, accused Nazism of being an atrociously dogmatic and intolerant religious movement, Hitler’s one-man theater, which would not withstand the test of logical analysis. Other prominent examples of those opposed to Japan’s pro-Nazi trend include Kiichiro HIGUCHI, Lieutenant General of the Imperial Japanese Army, who assisted Jewish refugees in their entry into Manchukuo, and Chiune SUGIHARA, the diplomat who issued Jewish refugees with transit visas against the orders of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The newspaper coverage of the Jews who arrived at Tsuruga with Sugihara visas did not accurately reflect the actual treatment of the refugees by the local residents. -

Notice Regarding Partnership Termination with the Asahi Shimbun

December 12, 2019 Name of Company Demae-can Co., Ltd Representative Rie Nakamura, President & CEO (JASDAQ Code:2484) Contact Corporate Planning Group Group Manager, Masamichi Azuma TEL:+81 3 4500 9386 URL:https://corporate.demae-can.com/en/ Notice Regarding Partnership Termination with The Asahi Shimbun - Further development of the sharing delivery business with “ASA (Asahi newspaper delivery offices)” - Demae-can Co., Ltd (hereinafter referred to as the “Company”) hereby announces that the Board of Directors resolved on December 12, 2019 to terminate the business partnership agreement with The Asahi Shimbun (Headquarters: 2-3-18 Nakanoshima, Kita-ku, Osaka, Japan; President and CEO: Masataka Watanabe), effective on June 14, 2020. 1. Reasons for the partnership termination The Company concluded a business partnership agreement with The Asahi Shimbun on December 15, 2016 with the aim of developing and expanding the new business model of the Sharing Delivery. The Company has since achieved successful results in expanding the Sharing Delivery service in collaboration with The Asahi Shimbun’s newspaper delivery offices, known as “ASA” nationwide, developing cooperative service opportunities with almost all of the ASA offices that had expressed interest in the new service endeavor. The Company has also achieved significant expansion in service areas through partnerships with some community-based local forwarders and enhanced delivery networks that are operated directly by the Company along with the collaborative efforts with ASA offices. Given this situation, the Company has decided to terminate the partnership with The Asahi Shimbun after reevaluating the agreement for achieving further expansion in the number of the sharing delivery hubs, partner restaurants and service users with a stronger sense of urgency.