Millikin University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

2012-13 Academic Catalog

Academic Catalog 2012-13 Table of Contents Academic Calendar Accreditation and Compliance Statements Alma College in Brief Section I: General Information A College of Distinction Admission Information Accelerated Programs and Advanced Placement Options Scholarships and Financial Assistance College Expenses Living on Campus College Regulations The Judicial Process The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and Alma Academic Support Facilities Specialized Services Section II: Academic Programs and Opportunities Requirements for Degrees General Education Goals Guide to General Education Distributive Requirements Academic Honors Faculty Recognition Academic Rules and Procedures Honors Program Interdisciplinary Programs Leadership Programs Pre-Professional Programs Off Campus Study Programs Section III: Courses of Instruction Courses of Instruction Guide to Understanding Course Listings General Studies American Studies (AMS) Art and Design (ART) Astronomy (AST) Biochemistry (BCM) Biology (BIO) Biotechnology (BTC) Business Administration (BUS) Health Care Administration (HCA) International Business Administration (IBA) Chemistry (CHM) Cognitive Science (COG) Communication (COM) Computer Science (CSC) Economics (ECN) Education (EDC) English (ENG) Environmental Studies (ENV) Foreign Service (FOR) Geography (GGR) Geology (GEO) Gerontology (GER) History (HST) Integrative Physiology and Health Science (IPH) Athletic Training (ATH) Public Health (PBH) Library Research (LIB) Mathematics (MTH) Modern Languages French (FRN) German (GRM) Spanish (SPN) -

Illinois Wesleyan Invitational Ironwood Normal, IL Ironwood GC Men Dates: Apr 02 - Apr 03

Illinois Wesleyan Invitational Ironwood Normal, IL Ironwood GC Men Dates: Apr 02 - Apr 03 Start Finish Player Team Scores - 1 Rob Wuethrich Illinois Wesleyan 67 -5 - T2 Carson Brock Wisconsin - Eau Claire 70 -2 - T2 Justin Park Illinois Wesleyan 70 -2 - 4 Will Hocker Webster 71 -1 - T5 Jimmy Morton Illinois Wesleyan 72 E - T5 Craig Schlegel Aurora University 72 E - T7 Scott Boyajian Aurora University 73 +1 - T7 Matthew Davidson Edgewood College 73 +1 - T9 Wyatt Wasko Gustavus Adolphus 74 +2 - T9 Isaac Prefontaine Wisconsin - Eau Claire 74 +2 - T9 Will Nummy Illinois Wesleyan 74 +2 - T9 Ethan Wilkins Illinois Wesleyan 74 +2 - T9 Zachary Shawhan Carthage College 74 +2 - T14 Keegan Adamson Illinois Wesleyan 75 +3 - T14 Cole Pickett Webster 75 +3 - T14 Tyler Reitz Millikin University 75 +3 - T14 Andrew Schrader Aurora University 75 +3 - T14 Noah Hogue Aurora University 75 +3 - T14 Harold Dobernecker Central College (IA) 75 +3 - T14 Josh Hentrich Edgewood College 75 +3 - T14 James Gilmore DePauw University 75 +3 - T14 Will Osborn Wabash College 75 +3 - T14 Jack Dwyer Lake Forest College 75 +3 - T24 Hayden Henry Illinois Wesleyan 76 +4 - T24 Jack Vercautrer Aurora University 76 +4 - T24 John Hudson * Aurora University 76 +4 - T24 Dustin Haines Central College (IA) 76 +4 - T24 Jack Haberkorn North Park University 76 +4 - T29 Matt Fladten Wisconsin - Eau Claire 77 +5 - T29 Tommy Hinker Gustavus Adolphus 77 +5 - T29 Jacob Kelber DePauw University 77 +5 - T32 Jacob Pedersen Gustavus Adolphus 78 +6 - T32 Corey Boerner Wisconsin - Eau Claire 78 +6 -

The Student Body: 1958

Volume 8 Autumn, 1958 Number 1 The Student Brandeis University College of the Holy Cross Body: I958 Brigham Young University Hope College University of British Columbia College of Idaho of Idaho The current student of the Law School is made Brooklyn College University body Brown University Illinois College of residents of a and up great many states, graduates Cairo University (Egypt) Illinois Institute of Technology of an even larger number of universities and colleges. University of California University of Illinois The total enrollment of 352 includes students who Calvin College Indiana University Carleton College Johns Hopkins University make their homes in the states: following University of Chicago University of Kansas The Citadel Kent State University Alabama Michigan City College of San Francisco Kenyon College Alaska Minnesota Clark Junior College Knox College Arizona Missouri Coe College Lake Forest College California Montana Colby College Lawrence College Colorado Nebraska Colgate University University of Leiden (Nether- Connecticut New Jersey University of Colorado lands) Delaware New York Columbia University London School of Economics District of Columbia North Carolina University of Connecticut Louisville Municipal College . Florida Ohio Cornell University Loyola University (Chicago) Georgia Oregon Dartmouth College Macalester College Idaho Pennsylvania Davidson College University of Maine Illinois Rhode Island Denison University University of Marburg Indiana South Dakota DePaul University (Germany) Iowa Tennessee DePauw University -

LU12- LCIE Catalog 2012.Indd

2012/2013 LCIE Catalog -JOEFOXPPE6OJWFSTJUZtSaint Charles, Missouri Founded 1827 2012/2013 Academic Programs UNDERGRADUATE DEGREES Business Administration (B.S.) Communications (B.A.) Communications, Corporate Communications Emphasis (B.A.) Communications, Mass Communication Emphasis (B.A.) Criminal Justice (B.S.) Fire Science Management (B.S.) Health Management (B.S.) Human Resource Management (B.S.) Information Technology (B.S.) Information Technology, Multimedia Emphasis (B.S.) Information Technology, Networking and Operating Systems Emphasis (B.S.) Information Technology, Programming and Database Emphasis (B.S.) Mortuary Management (B.S.) POST BACHELOR CERTIFICATE Information Technology GRADUATE DEGREES Master of Business Administration (M.B.A.) Master of Science in Administration, Management Emphasis (M.S.A.) Master of Science in Administration, Marketing Emphasis (M.S.A.) Master of Science in Administration, Project Management Emphasis (M.S.A.) Master of Arts in Communication, Digital and Multimedia Emphasis (M.A.) Master of Arts in Communication, Media Management Emphasis (M.A.) Master of Arts in Communication, Promotions Emphasis (M.A.) Master of Arts in Communication, Training and Development Emphasis (M.A.) Masters of Science in Criminal Justice Administration (M.S.) Master of Arts in Gerontology (M.A.) Master of Science in Healthcare Administration (M.S.) Master of Science in Human Resource Management (M.S.) Master of Science in Managing Information Technology (M.S.) Master of Fine Arts in Writing (M.F.A.) On the cover: From left to right, LCIE students Molly Ell, Robert Powell, Terry Brunner, Amy Baue, Jacqueline Nelson, and Jared Elder. -JOEFOXPPE6OJWFSTJUZt-$*&$BUBMPH Table of Contents Academic Programs . 1 Refund Distribution of Financial Aid .................... 16 Academic Calendar . 5 Cash Disbursements ................................ -

Member Colleges & Universities

Bringing Colleges & Students Together SAGESholars® Member Colleges & Universities It Is Our Privilege To Partner With 427 Private Colleges & Universities April 2nd, 2021 Alabama Emmanuel College Huntington University Maryland Institute College of Art Faulkner University Morris Brown Indiana Institute of Technology Mount St. Mary’s University Stillman College Oglethorpe University Indiana Wesleyan University Stevenson University Arizona Point University Manchester University Washington Adventist University Benedictine University at Mesa Reinhardt University Marian University Massachusetts Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Savannah College of Art & Design Oakland City University Anna Maria College University - AZ Shorter University Saint Mary’s College Bentley University Grand Canyon University Toccoa Falls College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Clark University Prescott College Wesleyan College Taylor University Dean College Arkansas Young Harris College Trine University Eastern Nazarene College Harding University Hawaii University of Evansville Endicott College Lyon College Chaminade University of Honolulu University of Indianapolis Gordon College Ouachita Baptist University Idaho Valparaiso University Lasell University University of the Ozarks Northwest Nazarene University Wabash College Nichols College California Illinois Iowa Northeast Maritime Institute Alliant International University Benedictine University Briar Cliff University Springfield College Azusa Pacific University Blackburn College Buena Vista University Suffolk University California -

Academic Consortium Membership Benefits

Founded in 1947, CIEE: Council on FACULTY-LED AND CUSTOM PROGRAMS International Educational Exchange is a Programs provide the tools you need to plan and deliver world leader, delivering the highest- academically rigorous, culturally rich programs around the world. quality programs that increase global understanding and intercultural knowledge. INTERNATIONAL FACULTY DEVELOPMENT SEMINARS Faculty can choose from several international seminars STUDY ABROAD PROGRAMS that will help enhance syllabi, internationalize curricula, and enrich on-campus research. More than 220 programs. 43 countries. 60 cities. Around Council on International 2016 the world, CIEE programs provide skills, competencies, Educational Exchange CIEE ANNUAL CONFERENCES and experiences that create global citizens. 300 Fore St. CIEE holds events that offer professional development, Portland, ME 04101 SCHOLARSHIPS AND GRANTS access to best practices in program delivery, and peer 1-800-40-STUDY CIEE improves access through annual student networking opportunities. ACADEMIC CONSORTIUM Founded in 1947, CIEE is the world leader in international education financial aid giving of more than $3 million. and exchange, delivering the highest-quality programs that increase global understanding and intercultural knowledge. We provide participants with skills, competencies, and experiences that elevate their ability to contribute positively to our global community. MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS ciee.org/study © Copyright CIEE 2015. All rights reserved. ciee.org/study ACADEMIC CONSORTIUM MEMBER INSTITUTIONS -

MOACAC Member Colleges for 2020-21 School Year Arkansas

MOACAC Member Colleges for 2020-21 School Year Arkansas State University Avila University Baker University Ball State University Baylor University Bellarmine University Belmont University Beloit College Benedictine College Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing and Health Sciences Bradley University Brescia University Butler University Central Christian College of the Bible Central Methodist University Centre College Cleveland University-Kansas City Coe College College of the Ozarks Columbia College Columbia College Chicago Cottey College Creighton University Crowder College Culver-Stockton College DePaul University DePauw University Dominican University Donnelly College Drake University Drury University Earlham College East Central College Eastern Illinois University Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Emporia State University Evangel University Florida Southern College Fontbonne University Franklin College Gettysburg College Goldfarb School of Nursing at Barnes Jewish College Graceland University Grand Canyon University Hannibal-LaGrange Univesity Hanover College Harris-Stowe State University Illinois College Illinois Institute of Technology Illinois State University Illinois Wesleyan University Indian Hills Community College Indiana State University Indiana University Bloomington Indian Hills Community College Iowa State University Iowa Wesleyan University Jefferson College Johnson & Wales University Johnson County Community College Kansas City Art Institute Kansas State University Knox College Lake Forest College Lewis University Lincoln -

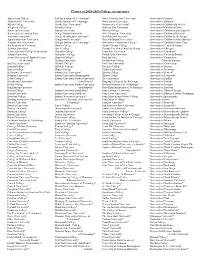

Classes of 2010-2018 College Acceptances

Classes of 2010-2018 College Acceptances Agnes Scott College Fashion Institute of Technology* North Carolina State University University of Arizona Alaska Pacific University Florida Institute of Technology Northeastern University University of Baltimore Albion College Florida State University* Northwestern University* University of California Berkeley* Allegheny College Franklin College Oakland City University University of California Davis American University Furman University Oberlin College University of California-Los Angeles* American University of Paris George Mason University Olivet Nazarene University University of California Riverside Anderson University* George Washington University* Oral Roberts University University of California San Diego* Appalachian State University Georgetown University* Ouachita Baptist University* University of California-Santa Barbara* Arizona State University* Georgia Institute of Technology* Owensboro Community College* University of California Santa Cruz Art Academy of Cincinnati Goshen College Ozark Christian College University of Central Arkansas Ashland University Grace College Parsons The New School for Design University of Chicago* Atlas University College-Netherlands Hamilton College Penn State University University of Cincinnati* Auburn University Hampshire College Philadelphia University University of Colorado Boulder Avans University of Applied Science Hanover College* Pratt Institute University of Colorado at -Netherlands Harding University Presbyterian College Colorado Springs* Ball State -

Rhodes College Fall Classic Tunica National 2018 Rhodes Fall Collegiate Dates: Sep 23 - Sep 24

Rhodes College Fall Classic Tunica National 2018 Rhodes Fall Collegiate Dates: Sep 23 - Sep 24 Pos. Team/Player (seed) Rd 1 Rd 2 Total T1 Huntingdon College 283 282 565 2 Henry Gee (3) 68 67 135 T8 Drew Mathers (1) 70 71 141 T28 Stephen Shephard (2) 73 72 145 T31 Carson Whitton (4) 74 72 146 T31 Wyatt Adkison (5) 72 74 146 T1 UT Tyler 283 282 565 1 Tyler Uhlig (1) 68 66 134 T17 Jeff Murphy (2) 69 74 143 T17 Nicklaus Cuny (4) 73 70 143 T28 Hayden Montoya (3) 73 72 145 T44 Tanner Saul (5) 73 75 148 3 LaGrange College 288 285 573 T17 Ben Womack (1) 71 72 143 T17 Mathias Andersen (4) 72 71 143 T22 Sam Rogers (2) 72 72 144 T44 Rob Simpson (3) 73 75 148 T70 Cameron Starr (5) 82 70 152 4 Rhodes College 287 287 574 T8 Vince Wheeler (5) 72 69 141 T13 Tom Weaver (4) 70 72 142 T22 Hunter Bremer (1) 72 72 144 T38 Tyler Cohen (3) 73 74 147 T53 Corrie Kuehn (2) 76 74 150 5 Southwestern Univ. 298 281 579 T5 Sutherland Stith (2) 74 66 140 T13 Cade Osgood (1) 72 70 142 T38 John Kellum (3) 75 72 147 T53 Devon Horne (4) 77 73 150 T53 Andrew Augustine (5) 77 73 150 6 Transylvania 291 289 580 T5 Spencer McKinney (4) 68 72 140 T31 Jack Berger (1) 74 72 146 T38 Harrison Lane (2) 74 73 147 T38 Zach Treilobs (5) 75 72 147 T70 Blake Young (3) 76 76 152 7 Berry College 289 293 582 T8 Wesley Heston (3) 67 74 141 T17 Preston DeSantis (1) 71 72 143 T31 Henry Jones (2) 73 73 146 T70 Andrew Porter (5) 78 74 152 T86 Jeremy Smith (4) 79 76 155 GOLFSTAT COLLEGIATE SCORING SYSTEM Mark Laesch - COPYRIGHT © 2021, All Rights Reserved, Golfstat Pos. -

ACI Reporter Winter 2015

Winter 2015 In This Issue Leadership Message: Looking Forward ACI News: ACI Awarded Challenge Grant for Peer Mentoring Program ACI Scholars: Natalie Miles, Millikin University ACI Scholars: Christopher Paepke, Trinity Christian College ACI Scholars: Joseph Bezenek, Millikin University Your Gift to ACI Meet ACI Members: Concordia University Chicago Meet ACI Members: Monmouth College Did You Know? Research shows private liberal arts colleges are more cost- effective than public institutions Thank You! open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Looking Forward As I write this, I'm grateful for what we have accomplished in 2015. We've listened to you, enhanced our operations and refocused our work as we prepare to begin a new calendar year. For 2016, ACI has many exciting ideas and plans, and I'd like to share them with you. We will: focus on ACI's main responsibilities of raising scholarship funds, growing its peer-mentoring efforts at member colleges and universities, and offering solid continuing education programs through our four types of conferences. continue to share the value of liberal arts education with ACI's corporate partners and sponsors, and we're planning more outreach. enter a detailed planning process in early 2016, with the goal of developing a three-year strategic plan, plus annual business plans. strengthen our network of 23 colleges and universities in Illinois, and partnerships with national organizations such as the Council of Independent Colleges (CIC). Finally, we have reconstituted ACI's board of trustees and its roles and responsibilities, and plan to strengthen the organization's leadership throughout all of Illinois. -

Holy Innocents' Class of 2021 Admitting Colleges And

Holy Innocents’ Class of 2021 Admitting Colleges and Matriculations* Agnes Scott College Emerson College Montclair State University Alabama A & M University Emory University Montreat College American University Fairfield University New York University Amherst College Fashion Institute of Technology North Carolina A & T State University Appalachian State University Flagler College North Carolina Central University Arizona State University Florida A & M University North Carolina State University Auburn University (19) Florida International University North Central College Babson College Florida State University (2) Northeastern University Barry University Fordham University Northwestern University Baylor University Furman University Nova Southeastern University Belmont University The George Washington University Oberlin College Berry College Georgetown University Occidental College Birmingham-Southern College Georgia College Oglethorpe University Boston College Georgia Institute of Technology (8) Pace University Boston University Georgia Southern University (2) Pennsylvania State University Bowdoin College Georgia State University (3) Pepperdine University Bradley University Guilford College Presbyterian College Butler University Hampden-Sydney College Purdue University California Institute of the Arts Hampton University Rhodes College Carleton College Hofstra University Rice University Catholic University of America Howard University Rider University Centre College Hult International Business School Robert Morris University Chapman University