Ekrakhmalnikov Morethanapar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Hundred-Names

l LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 1. Bd 30. Nr 1. ,~ ,j .11 . i ~ .l i THE jl; ENGLISH HUNDRED-NAMES BY oL 0 f S. AND ER SON , LUND PHINTED BY HAKAN DHLSSON I 934 The English Hundred-Names xvn It does not fall within the scope of the present study to enter on the details of the theories advanced; there are points that are still controversial, and some aspects of the question may repay further study. It is hoped that the etymological investigation of the hundred-names undertaken in the following pages will, Introduction. when completed, furnish a starting-point for the discussion of some of the problems connected with the origin of the hundred. 1. Scope and Aim. Terminology Discussed. The following chapters will be devoted to the discussion of some The local divisions known as hundreds though now practi aspects of the system as actually in existence, which have some cally obsolete played an important part in judicial administration bearing on the questions discussed in the etymological part, and in the Middle Ages. The hundredal system as a wbole is first to some general remarks on hundred-names and the like as shown in detail in Domesday - with the exception of some embodied in the material now collected. counties and smaller areas -- but is known to have existed about THE HUNDRED. a hundred and fifty years earlier. The hundred is mentioned in the laws of Edmund (940-6),' but no earlier evidence for its The hundred, it is generally admitted, is in theory at least a existence has been found. -

The 1548 Dissolution of the Chantries and Clergy of the Midland County Surveys

MANAGING CHANGE IN THE ENGLISH REFORMATION: THE 1548 DISSOLUTION OF THE CHANTRIES AND CLERGY OF THE MIDLAND COUNTY SURVEYS BY SYLVIA MAY GILL A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern History College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham March 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. INFORMATION FOR ABSTRACTING AND INDEXING SERVICES The information on this form will be published. To minimize any risk of inaccuracy, please type your text. Please supply two copies of this abstract page. Full name (surname first): Gill, Sylvia May School/Department: School of History and Cultures/Modern History Full title of thesis/dissertation: Managing Change in The English Reformation: The 1548 Dissolution of the Chantries and Clergy of the Midland County Surveys Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Date of submission: March 2010 Date of award of degree (leave blank): Abstract (not to exceed 200 words - any continuation sheets must contain the author's full name and full title of the thesis/dissertation): The English Reformation was undeniably a period of change; this thesis seeks to consider how that change was managed by those who were responsible for its realisation and by individuals it affected directly, principally during the reign of Edward VI. -

Annual Report No. 72 2005 the Birds of Staffordshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire and the West Midlands 2005

West Midland Bird Club Annual Report No. 72 2005 The Birds of Staffordshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire and the West Midlands 2005 Annual Report 72 Editor D.W. Emley Published by West Midland Bird Club 2007 Published by West Midland Bird Club © West Midland Bird Club All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the copyright owners. The West Midland Bird Club is a registered charity No. 213311. Website: http://www.westmidlandbirdclub.com/ ISSN 1476-2862 Printed by Healeys Printers Ltd., Unit 10, The Sterling Complex, Farthing Road, Ipswich, Suffolk IP1 5AP. Price £9.00 The Birds of Staffordshire, Warwickshire, Worcestershire and the West Midlands 2005 Annual Report 72 Contents 4 Editorial 5 Submission of Records 6 Birds and Weather in 2005 14 Systematic List 222 Ringing in 2005 228 Belted Kingfisher – a first for the Region 229 Aquatic Warbler in Warwickshire – a first for the county 230 The Farnborough Lesser Scaup – second record for the Region 232 County Lists 239 Gazetteer 247 List of Contributors 251 Index to Species Front Cover Photograph: Waxwing at Coleshill, Steve Valentine 3 Editorial A huge amount of work goes into the production of this Report so I would like to offer my sincere thanks to the production team for their sterling efforts in reducing the backlog to the extent that this year we have been able to publish two Reports – no mean task! It is encouraging to see the increase in the number of contributors (over 330), many of these now submitting records by BTO’s Birdtrack. -

Land Off Westham Lane Barford Warwickshire

Land off Westham Lane Barford Warwickshire Post-Excavation Assessment and Updated Project Design for Taylor Wimpey West Midlands CA Project: 669022 CA Report: 17048 February 2017 Land off Westham Lane Barford Warwickshire Post-Excavation Assessment and Updated Project Design CA Project: 669022 CA Report: 17048 prepared by Julian Newman date October 2016 checked by Sarah Cobain, Post-Excavation Manager date February 2017 approved by Martin Watts, Head of Publications signed date February 2017 issue 01 This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. 1 Land off Westham Lane, Barford, Warwickshire: Post-Excavation Assessment and Updated Project Design © Cotswold Archaeology CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 5 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 6 Location, topography and geology ......................................................... 6 Project background ................................................................................ 7 Archaeological background ................................................................... 7 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES .................................................................................. -

The Lighthorne Loss Accounts of the English Civil Wars by Ann Such

1 LH235(E) The Lighthorne Loss Accounts of the English Civil Wars by Ann Such (2020) with contributions by Colin Such Introduction In late 2017 as archivist of the Lighthorne History Society, Colin was contacted by Dr Maureen Harris of Leicester University asking for volunteers. She explained that she had initiated a project on behalf of the Dugdale Society and supported by the Friends of Warwick County Record Office. She had applied for and been awarded a Heritage Lottery Fund grant with the aim of training inexperienced volunteers from history societies and parish and civic groups from all over 'old' Warwickshire to transcribe the Warwickshire Parliamentarian Loss Accounts. The Dugdale Society was founded in 1920 with the objects of publishing original documents relating to the history of the County of Warwick, fostering interest in historical records and their preservation and generally encouraging the study of local history. The Society is named after Sir William Dugdale, a famous 17th century antiquarian who was a strong supporter of Charles I. It is hoped that in 2020 the Dugdale Society will make the completed transcriptions publicly available on a searchable Warwickshire County Record Office website to accompany a volume of selected examples, with an introductory chapter and a full index, to be published possibly in 2021. Another aim of the project is to transmit knowledge about ‘Living through the English Civil Wars in Warwickshire’ to the history societies and other local groups linked to the volunteers. Colin and I volunteered for the project and on 15 November 2019 we jointly presented a talk to Lighthorne History Society based on the following text. -

A Brief Account of Some of the Significant Lighthorne Buildings By

A Brief Account of some of the significant Lighthorne Buildings by Colin Such (2012), based on research notes by Peter Hinman and archival material in the possession of the Lighthorne History Society. The Church St Laurence’s Church by Mark Thompson (1996) The Hwicce were an Anglian tribe who arrived in this area around 577 AD. Christianity was introduced to Lighthorne in 688 AD, when King Eanhere of the Hwicce became a Christian. The Diocese of Worcester was formed from the Kingdom of the Hwicce. A preaching cross was erected, probably in the 9 th or 10 th century. When the Domesday Book was compiled in 1087, Lighthorne was described as having a priest but no mention is made of a church. This is possible, as early services were often held in the open air by the preaching cross. The base of the cross is still visible in the churchyard. Photo Colin Such By 1298 there was a church valued at 26 marks included in the valuation when the estate passed to Guy, the 10 th Earl of Warwick. Later descriptions of this church indicate that it was a simple structure, consisting of a chancel, nave and wooden bell tower. The first recorded name of a Rector of Lighthorne is Henry de Hampton, who was invested on July 13 th 1307. The oldest church glass and oldest bell date from the accession of Henry V in 1413. The tower now contains 6 bells, 2 of which were cast in 2006. For further details of the bells see LH76 (E), in the Lighthorne History Society archive. -

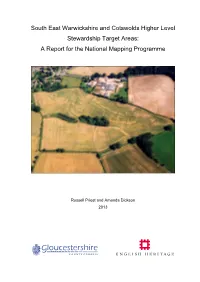

A Report for the National Mapping Programme English Heritage

South East Warwickshire and Cotswolds Higher Level Stewardship Target Areas: A Report for the National Mapping Programme Russell Priest and Amanda Dickson 2013 South East Warwickshire and Cotswolds Higher Level Stewardship Target Areas: A Report for the National Mapping Programme English Heritage; NHPCP Project No. 6053 Report Authors: Russell Priest and Amanda Dickson © English Heritage and Gloucestershire County Council 2013 Applications for report reproduction should be made to: English Heritage Archive Services The Engine House Fire Fly Avenue Swindon SN2 2EH Email: [email protected] Tel: 01793 414600 Fax: 01793 414707 DOCUMENT CONTROL GRID Title: South East Warwickshire and Cotswolds HLS Target Areas NMP. Report. Project number: NHPCP project 6053 Author(s): Russell Priest and Amanda Dickson (ed Toby Catchpole) Archaeology Service Gloucestershire County Council Shire Hall GLOUCESTER GL1 2TH Origination date: May 2013 Version: Draft Version 8 Reviser(s): AD final formatting Date of last revision: 11/03/14 Status: Final submission Summary of changes: Tidy illustrations, reference checks, final formatting Circulation: NHPCT, Helen Winton Required Action: Read through by SC and TC; Send to Helen Winton Approval: Copyright © English Heritage and Gloucestershire County Council 2013 CONTENTS DOCUMENT CONTROL GRID...........................................................................................................4 CONTENTS.........................................................................................................................................5 -

A SHORT HISTORY of LIGHTHORNE by PETER HINMAN

A SHORT HISTORY OF LIGHTHORNE By PETER HINMAN As a settlement, Lighthorne has existed for about four thousand years. Successive occupiers have left traces of their time here; burials and other remains from the Neolithic, Iron age, Roman, Anglian and early Christian period have been found within the parish. Major events in Britain's history, such as the Black Death, the Wars of the Roses, Reformation, Civil War and Enclosure acts have all had their impacts on the village story. Although Lighthorne lies close to the centre of modern England, for most of its long history it has been a frontier town, lying between conflicting tribal, political, religious and social boundaries. Located at the geological change from the limestones of the Cotswolds to the red earth of the Midlands plain, this natural frontier has shaped our early history. The Etymology of the Village Name. Modern etymology Midland Place Names (1992) indicates that the name “Lighthorne” was given to the village by the Middle Angles, the most recent wave of settlers to occupy the area. The name is of the type which would describe the land in a way which would mean something to newcomers, without the benefit of the written word. The first written reference to Lighthorne is the Domesday Book, giving the name as “Listecorne”. Later documents give spellings such as Lychtehurne (1252), Lytehurn (1301) Lyghteherne (1331). “Lighthorne” first appears in 1545. The earliest explanation of the name is in The Antiquities of Warwickshire by Sir William Dugdale (1656). “I am confident that the last Syllable should be ‘hirne’, which in our old English signifies a corner; and by which I guess at the former Syllable, Viz. -

Volume 05 Number 08

CAKE AND COCKHORSE Banbury Historical Society Spring 1974 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman and Magazine Editor: F. Willy, B.A., Raymond House, Bloxham School, Banbury Hon. Secretary : Assistant Secretary Hon. Treasurer: Miss C.G. Bloxham, B.A. and Records Series Editor: Dr. G.E. Gardam Banbury Museum J.S.W. Gibson, F.S.A. 11 Denbigh Close Marlborough Road 11 Westgate Broughton Road Banbury OX 16 8DF Chichester PO19 3ET Banbury OX16 OBQ (Tel. Banbury 2282) (Chichester 84048) (Tel. Banbury 2841) Hon. Research Adviser: Hon. Archaeological Adviser: E.R.C. Brinkworth,M.A., F.R.Hist.S. J.H. Fearon, B.Sc. Committee Members J.B. Barbour, A. Donaldson, J.F. Roberts ************** The Society was founded in 1957 to encourage interest in the history of the town of Banbury and neighbouring parts of Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire. The Magazine Cake & Cockhorse is issued to members three times a year. This includes illustrated articles based on original local historical research, as well as recording the Society’s activities. Publications include Old Banbury - a short popular history by E.R.C. Brinkworth (2nd edition), New Light on Banbur.v’s Crosses, Roman Banburyshire, Banbury’s Poor in 1850, Banbury Castle - a summary of excavations in 1972, The Building and Furnishing of St. Mary’s Church, Banbury, and Sanderson Miller of Radway and his work at Wroxton, and a pamphlet History of Banbury Cross. The Society also publishes records volumes. These have included Clockmaking in Oxfordshire, 1400- 18.50; South Newington Churchwardens’ Accounts 1553-1 684; Banbury Marriage Register, 1558-1837 (3 parts) and Baptism and Burial Register, 1558-1723 (2 parts); A Victorian M.P.