Volume 05 Number 08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epwell Grounds Farm 13/01600/F Shutford Road Epwell OX15 6HF

Epwell Grounds Farm 13/01600/F Shutford Road Epwell OX15 6HF Ward: Sibford District Councillor: Cllr. Reynolds Case Officer: Rebekah Morgan Recommendation: Approve Applicant: Mr Bart Dalla Mura Application Description: Solar Park Committee Referral : Major application Committee Date: 9 January 2014 1. Site Description and Proposal 1.1 The site is an area of farmland adjacent to Epwell Grounds Farm complex, which lies to the north of Epwell Road, approximately 950m to the south of the village of Shenington, 1.2km to the north-west of the village of Shutford and 850m to the west of The Plain Road. 1.2 The topography of the wider landscape is varied, scattered with a number of small hills. To the north-west of Shenington village is Shenington gliding club and airfield (1.2km from the site). 1.3 The site is made up of a single field currently under arable production with existing hedgerows along the boundaries. A public right of way is immediately adjacent to the site following the northern and eastern boundaries. 1.4 The proposal seeks consent for the construction of a solar park, to include the installation of solar panels to generate up to 7MW of electricity, with control room, fencing and other associated works. The application boundary measures 15.07 hectares; the number of individual panels has not been specified. 2. Application Publicity 2.1 The application has been advertised by way of a press notice, site notice and neighbour letters. The final date for comment on this application was 24th December 2013. One letter was received raising the following concerns: • Visual impact, being such a large site 3. -

Elms Road, Cassington, Witney, Oxfordshire, OX29 4DR Guide Price

Elms Road, Cassington, Witney, Oxfordshire, OX29 4DR A semi-detached House with 3 Bedrooms and a good size rear garden. Scope for extension possibilities and is offered with no onward chain. Guide Price £325,000 VIEWING By prior appointment through Abbey Properties. Contact the Eynsham office on 01865 880697. DIRECTIONS From the Eynsham roundabout proceed east on the A40 towards Oxford and after a short distance turn left at the traffic lights into the village of Cassington. Continue through the village centre, past the Red Lion Public House and Elms Road will be found a short distance afterwards on your left hand side. DESCRIPTION A well-proportioned 3 Bedroom semi-detached House dating from the 1950's with potential to extend and a larger than average garden overlooking allotment land at the rear. The property has been let for some years and as a result has been maintained and updated in parts with a refitted Kitchen and double glazing but there does remain some scope for further improvement and possible extension, subject to consents. The accommodation includes a double aspect Sitting Room, Dining/Playroom, Kitchen, Utility, a Rear Lobby with conversion possibilities, 3 Bedrooms and Bathroom. There is gas central heating, driveway parking at the front and a good sized rear garden enjoying an open aspect. Cassington is a very popular village lying just off the A40, 1 mile from Eynsham and in Bartholomew School catchment and some 5 miles west of Oxford. End of chain sale offering immediate vacant possession. LOCATION Cassington lies just north of the A40 and provides easy access to both Witney, Oxford, A34, A420 and the M40. -

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford

11 Witney - Hanborough - Oxford Mondays to Saturdays notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F Witney Market Square stop C 06.14 06.45 07.45 - 09.10 10.10 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.20 - Madley Park Co-op 06.21 06.52 07.52 - - North Leigh Masons Arms 06.27 06.58 07.58 - 09.18 10.18 11.23 12.23 13.23 14.23 15.23 16.28 17.30 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 06.35 07.06 08.07 07.52 09.27 10.27 11.32 12.32 13.32 14.32 15.32 16.37 17.40 Long Hanborough New Road 06.40 07.11 08.11 07.57 09.31 10.31 11.36 12.36 13.36 14.36 15.36 16.41 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 06.49 07.21 08.20 09.40 10.40 11.45 12.45 13.45 14.45 15.45 16.50 Eynsham Church 06.53 07.26 08.24 08.11 09.44 10.44 11.49 12.49 13.49 14.49 15.49 16.54 17.49 Botley Elms Parade 07.06 07.42 08.33 08.27 09.53 10.53 11.58 12.58 13.58 14.58 15.58 17.03 18.00 Oxford Castle Street 07.21 08.05 08.47 08.55 10.07 11.07 12.12 13.12 13.12 15.12 16.12 17.17 18.13 notes M-F M-F S M-F M-F S Oxford Castle Street E2 07.25 08.10 09.10 10.15 11.15 12.15 13.15 14.15 15.15 16.35 16.35 17.35 17.50 Botley Elms Parade 07.34 08.20 09.20 10.25 11.25 12.25 13.25 14.25 15.25 16.45 16.50 17.50 18.00 Eynsham Church 07.43 08.30 09.30 10.35 11.35 12.35 13.35 14.35 15.35 16.55 17.00 18.02 18.10 Eynsham Spareacre Lane 09.34 10.39 11.39 12.39 13.39 14.39 15.39 16.59 17.04 18.06 18.14 Long Hanborough New Road 09.42 10.47 11.47 12.47 13.47 14.47 15.47 17.07 17.12 18.14 18.22 Freeland Broadmarsh Lane 07.51 08.38 09.46 10.51 11.51 12.51 13.51 14.51 15.51 17.11 17.16 18.18 18.26 North Leigh Masons Arms - 08.45 09.55 11.00 12.00 13.00 -

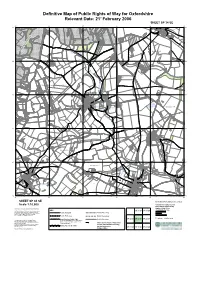

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21 February 2006

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SP 34 SE 35 36 37 38 39 40 255/2 1400 5600 0006 8000 0003 2500 4900 6900 0006 0006 5600 7300 0004 0004 2100 3300 4500 7500 1900 4600 6600 6800 A 422 0003 5000 0006 1400 2700 5600 7300 0004 0004 2100 3300 4500 5600 7500 0006 1900 4600 6600 6800 8000 0003 8000 2700 PAGES LANE Church CHURCH LANE Apple The The Yews Cottage 45 Berries 45 Westlynne West View Spring Lime Tree Cott School Cottage Rose Cottage255/2 255/11 Malahide The Pudlicote Cottage Field View Dun Cow 3993 WEST END 3993 Manor 255/6a Canada (PH) Cromwell Cottage House The 8891 8891 Cottage THE GREEN HORNTON 0991 Reservoir 25 (disused) 5/2a 3291 255/3 Pond Stable Cott 1087 1087 Foxbury Barn Foxbury Barn 1787 0087 0087 Sugarswell Farm Issues 2784 Sugarswell Farm 5885 2784 5885 The Nook 8684 8684 Holloway Drain House Hall 9083 9083 255/5 Rose BELL STREET Cottage Old Lodge FarmOld Lodge Farm Pricilla House Turncott 3882 Home Farm 3882 3081 3081 Old Post Cottage 2080 2080 Bellvue Water Orchard Cottage ndrush Walnut Bank Wi Pavilion Brae House 0479 0479 2979 Issues 1477 1477 Sheraton Upper fton Reaches Rise Gra Roseglen 0175 0175 ilee House Langway Jub Pond Tourney House 255/4 Drain Issues 255/2a Spring 3670 3670 Drain 5070 Temple Pool 2467 Hall 2467 82668266 Spring Spring 2765 43644364 5763 7463 3263 5763 7463 3263 255/3 0062 0062 0062 0062 Reservoir 7962 Issues (Disused) Issues Pond Spring 4359 4359 1958 1958 8457 0857 8457 0857 6656 6656 4756 7554 3753 2353 5453 3753 2353 5453 -

OLD BARN HOUSE Woodstock Road Witney Peace Amidst a Cotswolds Market Town… with Historic Oxford on Your Doorstep

OLD BARN HOUSE WOODSTOCK Road WITNEY Peace amidst a Cotswolds Market Town… with historic Oxford on your doorstep Witney is a Cotwolds market town that has it all, the honeyed stone buildings, the pretty River Windrush flowing through the town and the properly developed town centre with an excellent range of retailers, boutique shopping and 3 hour free parking to attract the buying public. With the historic city of Oxford only 13 miles away, this is a location that offers benefits for buyers who wish to be close to good independent schools, or those who may be ‘down- sizing’ and wish to be close to amenities in an attractive provincial town. Independent schools, Cokethorpe Preparatory School and St Hughs Preparatory School are both within 10 miles of the town and then there is a wide choice of high performing independent schools in Oxford, with an efficient school bus service on hand from Witney. There are rail connections London dotted around Witney in nearby Long Hanborough, Charlbury etc, which via the Great Western line offer ease of access to London. There is also the Oxford Parkway station north of the city, which offers a fast connection to London Marylebone Station. Exclusivity on the edge of the historic market town of Witney Style and quality… Set on the edge of historic Witney, Old Barn House is an individual, detached home of good scale, located in a generous, walled plot of just under 0.25 acres. The ground floor offers three versatile receptions rooms together with a spacious entrance hall, creating an immediate feel of space as you enter the house. -

Callow, Herbie

HERBERT (‘HERBIE’) CALLOW Herbie Callow, 81 years of age, is Deddington born and bred and educated in our village school; a senior citizen who has accepted the responsibilitiesoflife,hadfulfilmentinhiswork andovertheyearscontributedmuchtothe sporting acti vities of the village. Herecallsasalad,andlikeotheryouthsofhis agetakingpartintheworkinglifeofthevillage: upat6amtocollectandharnesshorsesforwork such as on Thursdays and Saturdays for Deely thecarrierhorses,pay1s.aweekandbreakfast, thenatnightfillingcoalbagsat2dpernight.At thattimecoalcametoAynhobybargeasdidthegraniteandstonechipsfor the roads. HespentashorttimeworkingattheBanburyIronworkingsandinSouthern IrelandwithvividmemoriesoftheSinnFinnriots.Helaterworkedfor OxfordshireCountyCouncilRoadDepartmentandreallythatwashisworking life.Intheearlydaystheroadsweremadeofslurriesinchipsandthenrolled bysteamroller,commentingthattheoddbanksatthesideofroadsweredue tothestintworkerscrapingmudofftheroads. DuringtheSecondWorldWarhewasamemberoftheAreaRescueTeam;the District Surveyor, Mr Rule, was in charge and Mr Morris was in charge of the HomeGuard. HerbiewasagangerontheOxfordby-passandrememberstheKidlington Zooandofthetimewhentwowolvesescaped.Helaterbecamegangforeman concernedwithbuildingbridges.Onehastorealiseatthatperiodthesmall andlargestreams,culvertsanddips,wereindividuallybridgedtocarryhorse -

Job 124253 Type

A SPLENDID GRADE II LISTED FAMILY HOUSE WITH 4 BEDROOMS, IN PRETTY ISLIP Greystones, Middle Street, Islip, Oxfordshire OX5 2SF Period character features throughout with an impressive modern extension and attractive gardens Greystones, Middle Street, Islip, Oxfordshire OX5 2SF 2 reception rooms ◆ kitchen/breakfast/family room ◆ utility ◆ cloakroom ◆ master bedroom with walk-in wardrobe and en suite shower room ◆ 3 additional bedrooms ◆ play room ◆ 2 bathrooms ◆ double garage ◆ gardens ◆ EPC rating = Listed Building Situation Islip mainline station 0.2 miles (52 minutes to London Marylebone), Kidlington 2.5 miles, M40 (Jct 9) 4.2 miles, Oxford city centre 4.5 miles Islip is a peaceful and picturesque village, conveniently located just four miles from Oxford and surrounded by beautiful Oxfordshire countryside. The village has two pubs, a doctor’s surgery and a primary school. The larger nearby village of Kidlington offers a wide range of shops, supermarkets and both primary and secondary schools. A further range of excellent schools can also be found in Oxford, along with first class shopping, leisure and cultural facilities. Directions From Savills Summertown office head north on Banbury Road for two miles (heading straight on at one roundabout) and then at the roundabout, take the fourth exit onto Bicester Road. After approximately a mile and a quarter, at the roundabout, take the second exit and continue until you arrive in Islip. Turn right at the junction onto Bletchingdon Road. Continue through the village, passing the Red Lion pub, and you will find the property on your left-hand side, on the corner of Middle Street. -

Farmers-Continued. Wicklow H

700 POST OFFICE COUNTIES FARMERs-continued. Wicklow H. Appleford, Abingdon Winders I. Steventon, Abingdon W eston H .Boscot, BroadLeaze, Lechlade WickR C. SmaH mead, Shinfield, Readng Windsor T. Know I hill, Maidenhead W eston J .Rectory fm.Ashron,Towcester Widdieon H. Gt. Harrowden, Wellingbro' Windsor T. ju11. Chalk Pit farm, Little• Weston J. jun, Marcb Baldon, Oxford Widley J. Burgbfield, Reading wick green Weston J, sen. March Baldon, Oxford Wiggins Mre. E. Teeton, Northampton Windsor T.sen. Littlewick gr. Maidenhd Wey J. Albury, Tetswortb Wiggins J. Orton, Kettering Wing W. Steeple Aston, Woodstock WheeldoB J. Vlaydon, Banbury Wiggins J. Stadhampton Wingfield H. H. Hurst, Reading Wheeler H.& J.Moat fm.Filkins,Lechlde Wiggins Mrs. M. Draughton,Nrthmptn Wink worth S. J. Hiddan farm,Hnngerfd Wheeler Mrs. E. Merton, Bicester Wiggins M. Ingham lane, Watlington Winterton J. Welton, Daventry Wheeler F. SunningweJI, Abingdon Wiggins R. DameHales'farm,Watlngtn WiseR. H. & T, West Hanney,Wantage Wheeler G. Kingham, Chipping Norton Wiggins R. Orton, Kettering Wise J. LowerGrange,Oddington,Oxfrd Wheeler I. Uffington, Faringdon Wiggins T. Dranghton, Norrhampton Wise J. Potterspnry, Stoney Stratford Wheeler J. Baywortb farm, Abingdon Wiggins T. Hook Norton, Banbury Wise J. Puxley, Stoney Stratford Wheeler J. Swallowfield, Reading Wiggins W. Draughton, Northampton Witherington C. Bradfield, Reading WheelerR.Blackthorn,Ambrosdn.Bicstr Wiggins W. Mill farm, Watlington Witheriogton C. H. 6onning, Reading Wheeler Mrs. S. Bradtield, Reading Wig"ginton Mrs.E. Glinton,Mkt.Deeping Withers G. Eastbury, Hungerford WbeelerT. White House farm, Wantage Wigginton J. Glinton, Market Deeping Withers J. Stokenchurch Wheeler W. Cbalgrove, Tetswortb Wigley J. Cholsey, Wallingford Withers J. -

Sibford Hvtrail

M 1 Theodore the Hermit A 4 2 3 For many years between the wars and until he died in 1950, Theodore Lamb lived the life of a recluse in a shack on Sibford Heath. A skilled watch and clock repairer, Theodore plied his trade around the local villages. He also played various instruments and posed for photographs for which he charged a fee of half a crown. He travelled around, sometimes on a bicycle without tyres, sometimes on foot, and usually with some form of truck loaded with junk and, in the winter, his fire in a bucket as well. He always paid for his small needs, although when his clothing, which was often made from sacks, Location Map became less than decent he was banned from Banbury and had to wait at the door of the village shop to be served. He was always totally honest and completely harmless despite his appearance. He Acknowledgements Thanks are due to the following with regard to the Historic Village Trail: was an immensely strong man and once pulled a chicken hut for Members of the Sibfords Society for researching and writing the leaflet. many miles back to Sibford taking several days over the journey. Nigel Fletcher for his watercolour illustrations. The owner of the Wykham Arms for allowing walkers to use the pub car park. The landowners, whose co-operation has helped to make the walk possible. Additional Information The text of this leaflet can be made available in other languages, large print, braille, audio or electronic format on request. Please contact 01295 227001. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Summer 2016 - What's New?

Summer 2016 - What's new? Over the past few months we have made huge progress with the Better Broadband rollout, connecting more remote areas of Oxfordshire than ever before. In achieving over 90 per cent of our superfast coverage target, we celebrated with the residents and businesses of Steeple Aston and Ashbury to welcome the faster connection that will have no end of benefits. This brings us one step closer to reaching our target of 95% of Oxfordshire premises to have access to superfast broadband services by December 2017. In this edition, find out when superfast broadband will be coming to a cabinet near you, read the coverage of our Steeple Aston and Ashbury events and learn about the independent assessment of superfast broadband coverage that is available from thinkbroadband®. Councillor Nick Carter, Cabinet Member for Business and Customer Services Coming to a cabinet near you! Since 1 July 2016, thirteen more cabinets have gone live – including cabinets providing superfast broadband to premises in the vicinity of: • Letcombe Regis • Thame town centre • Christmas Common • Woodcote, Reading • Businesses in the Granville Way/Launton Road area of Bicester • Fencott • Burdrop • Brewery Lane/Scotland End, Hook Norton In the coming weeks 4 more cabinets are expected to go live, providing superfast broadband to premises in the vicinity of: • Bletchingdon • Southam Road, Banbury • Shippon, Abingdon • Long Wittenham • Upper Heyford For further updates about our delivery plans see the coverage map on the Better Broadband for Oxfordshire website. Better broadband reaches remote areas Residents, local businesses and representatives from the Better Broadband for Oxfordshire partnership were in Ashbury on Friday 29 July to celebrate the village becoming the first area of the district to benefit from the second phase of the roll- out with around 230 premises able to access faster fibre broadband. -

![Oxon.] ADDERBURY (EAST.) 595](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5192/oxon-adderbury-east-595-775192.webp)

Oxon.] ADDERBURY (EAST.) 595

Oxon.] ADDERBURY (EAST.) 595 . Lenthall E. K. Esq. Besselsleigh Reade E. A. Esq. O.B. Ipsden house Lovedl1Y J. E. T. Esq. Williamscote, Reade William Bar., Esq. 11, St. Mary Banbury Abbot terrace, Kensington, W. Lybbe P. L. P. Esq. Holly-copse, near Reynardson H. B. Esq. Adwell house Reading Risley H. Cotton, Esq. Deddington Macclesfield Right Hon. the Earl of, Sartoris C. Esq. Wilcote Shirburn castle Simonds H. J. Esq. Caversham lIIackenzie Edward, Esq. Fawley court Southby Philip, Esq. Bampton Mackenzie W. D. Esq. Gillotts Spencer Col. the Hon. R. C. H. Oombe Marlborough His Grace the Duke of, Spencer Rev. Charles Vere, Wheatfield Lord Lieutenant. Blenheim palace Stonor Hon. F. 78, South Audley st. W. Marriott Edward J. B. Esq. Burford Tawney Archer R. Esq. Wroxton Marsham Robert Bullock, Esq. D.C.L. Taylor E. 'Vatson, Esq. Headington Merton College, Oxford Taylor Thomas, Esq. Aston Rowant Marsham O. J. B. Esq. Oaver3field Thomas 001. H. J. R.A. Woodstock Mason James, Esq. Eynsham hall house Melliar W. M. Foster, Esq. North Aston Thomson Guy, Esq. Baldon house Miller Lieut.-Col J. Shotover house Thornhill Charles E. Esq. (Vice Ohair- Milward, George, Esq. Lechlade manor man of Quarter Sessions), Woodleys Norreys Lord, 12, Charles st. Berkeley Valentia Right Hon. Viscount (High square, W. Sheriff), Bletchingdon park Norris Henry, Esq. Swalcliffe park Vanderstegen William Henry, Esq. Norris Henry O. Esq. Ohalcomb Oane-end-house, near Reading North 001. J. S. M.P. Wroxton abbey Vice-Chancellor Rev. of the University Parker Viscount, Shirburn castle of Oxford, Oxford Parry J. B.