Upper Palaeolithic & Mesolithic Buckinghamshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russets Bolter End

Russets Bolter End Russets Bolter End Buckinghamshire HP14 3NB - Tenure:- Freehold - OIEO £750,000 - Local Authority WDC - EPC Rating D (61/77) A fabulous 4/5 bedroom detached home offering flexible open plan living with spacious rooms located in the semi rural hamlet of Bolter End yet enjoying excellent transport links. The accommodation briefly comprises on the ground floor, entrance hall, cloakroom, sitting room with inset log burner, large living/dining space with French doors opening onto the “A fantastic individual 4/5 rear entertaining space, well equipped kitchen with integrated appliances and good size family room/bedroom. On the first bedroom detached home floor the double aspect master bedroom has built in storage and en suite bathroom, there are 3 further double bedrooms offering spacious versatile all with eaves wardrobe storage and superb principal bathroom with Jacuzzi bath and separate shower. Outside living with extensive rear there is a purpose built annex/studio with under floor heating, ample off road parking, and an extensive southerly facing garden & self-contained secluded rear garden with entertaining terrace, purpose built covered gazebo, tree house and storage shed. The property annex” benefits from a wet under floor heating to the ground floor, oil fired central heating to the first floor, double glazing and is sold with NO ONWARD CHAIN. The school bus stop is close by giving access to the schools in Marlow and High Wycombe. Bolter End is a hamlet approximately 5 miles to the west of High Wycombe, and 5 miles to the North of Marlow. There is an abundance of walks and bridleways in the vicinity, and local hostelries and amenities are a short drive away in the village of Lane End. -

Your Parish Magazine with News and Views from Bolter End, Cadmore

Spring 2020 1,750 copies distributed free the Your parish magazine with news and views from Bolter End, ClarCadmore End, Lane End, Moorio End and Wheelern End AptÊHeatingÊServices GasÊSafeÊRegisteredÊEngineers RegisteredÊNo.Ê209175 LocalÊServicesÊOffered • General Plumbing • Installation Work Ê• Free Estimates • Full Gas Central Heating installations undertaken • Boilers replaced and your options explained in laymans terms • Warm Air Units upgraded or removed • Radiators added and sytems updated or altered • All domestic natural gas appliances installed and serviced including gas fire cookers and hobs • Breakdown repairs on all Natural Gas appliances • Fast, friendly service at a fair price • Full references from satisfied local customers available on demand Tel:Ê07941Ê286747 AptÊHeatingÊServices,ÊLaneÊEnd BestÊprices,ÊServiceÊandÊreliabilityÊfromÊ aÊmatureÊlocalÊtradesmen Useful Telephone Numbers... Two Certificate of Excellence winners… Parish Clerk—Hayley Glasgow 01494 437111 Lane End Surgery 01494 881209 “Everything was perfect” Lane End Pharmacy 01494 880774 “Fabulous Sunday Roast Travelled 8 miles but worth NHS Direct 111 / 0845 46 47 every mile - excellent!!!” Lane End Holy Trinity Church 01494 882644 “it was so good! Super good pricing and tasty food.” Lane End Primary School 01494 881169 “…little Buckinghamshire gem.” Lane End Village Hall 01865 400365 “A lovely pub in beautiful Frieth Village Hall 01494 880737 countryside.” Lane End Youth & Community Centre 883878 / 07932 326046 Grouse & Ale - Lane End Yew Tree - Frieth Elim -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment Single Detached

Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment For Single Detached Dwelling , Finings Road, Bolter End, Buckinghamshire Document 756 LVIA Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment Introduction This assessment will not follow in detail the Landscape and Visual Guidelines (3rd Edition) as the content is not relevant in its entirety for a development of this size. It will review the potential impact of the proposed development visually and in terms of the landscape character. Whilst assessing the landscape and visual impact, the study will not make any assessments on scale, magnitude of effect, reversibility and other factors concerned with the degree of these effects. It will, however, set out the Zone of Visual Influence which indicates the limits of the area over which there is a visual or landscape impact on people, living, working, walking or driving within the local area from the proposed development. The assessment was undertaken by the applicants who are retired landscape architects, former members of the Landscape Institute and with more than thirty years’ experience of undertaking such assessments. Methodology The site was surveyed on the weekend of 10/11th October 2020 in bright, clear conditions. The survey assessed the visibility of the site and the dwelling which might be observable from the road and footpath network and from adjacent dwellings and commercial enterprises. It seeks to assess the landscape character based on the broad characteristics set out in the ‘Wycombe Landscape Character Assessment’ 2011 prepared by Land Use Consultants. Local Landscape Character The Wycombe Landscape Character Assessment placed the landscape which surrounds the proposed development into LCA 16.1 Stokenchurch Settled Plateau. -

Picture Postcard Midsomer Postcard Picture - Marlow

and Princes Risborough are about 30 minutes away. minutes 30 about are Risborough Princes and Marlow Carnival; Santa Fun Run and Swan Upping. Swan and Run Fun Santa Carnival; Marlow and brewery shops. brewery and Marlow Town Regatta; theatre at Wycombe Swan; Pop-up cinema; town walks; walks; town cinema; Pop-up Swan; Wycombe at theatre Regatta; Town Marlow 15 minutes from Marlow, and Beaconsfi eld, Windsor Windsor eld, Beaconsfi and Marlow, from minutes 15 tastings, open nights nights open tastings, Here are just a few… Pub in the Park; Marlow Players amateur dramatics; dramatics; amateur Players Marlow Park; the in Pub few… a just are Here Marlow, Cookham, Hurley and Henley are each about about each are Henley and Hurley Cookham, Marlow, the area, each offering offering each area, the Events over 30 other fi lming locations in the local area. Little Little area. local the in locations lming fi other 30 over now well established in in established well now Marlow is an excellent base from which to explore explore to which from base excellent an is Marlow Brewing Co. Ltd are are Ltd Co. Brewing Midsomer fi lming locations in red in locations lming fi Midsomer Rebellion and Fisher’s Fisher’s and Rebellion and cycling leafl ets as well as postcards and souvenirs. and postcards as well as ets leafl cycling and buckinghamshire/marlow Luxters’ brand. Both Both brand. Luxters’ www.treasuretrails.co.uk/things-to-do/ • Murder Mystery Trails Trails Mystery Murder • events, accommodation, attractions, walks walks attractions, accommodation, events, liqueurs -

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Weekly List of Planning Applications Planning & Sustainability 11 April 2019 1 14/2019 Link to Public Access NOTE: To be able to comment on an application you will need to register. Wycombe District Council WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED 10.04.19 Wycombe District Council 19/05275/FUL Received on 01.04.19 Target Date for Determination: 27.05.2019 Other Auth. Ref: Location : 25 Orchard Close Hughenden Valley Buckinghamshire HP14 4PR Description : Householder application for construction of an open front porch, insertion of a dormer window to the front roof elevation and bay window with roof Applicant : Mr Martin Sweeney 25 Orchard Close Hughenden Valley Buckinghamshire HP14 4PR Agent : Parish : Hughenden Parish Council Ward : Greater Hughenden Officer : Valerie Bailey Level : Delegated Decision 19/05526/FUL Received on 29.03.19 Target Date for Determination: 24.05.2019 Other Auth. Ref: MR SIMON ROGERS Location : Terriers Lodge Amersham Road High Wycombe Buckinghamshire HP13 5AJ Description : Construction of 3 bed detached dwellinghouse with associated landscaping, parking with access from Amersham Road Applicant : Mr Adrian White 67 Verney Avenue High Wycombe HP13 5AJ Agent : Eddy Fiss Design 38 Adelaide Strand Road Sandymount Dublin D04 F6F9 Parish : High Wycombe Town Unparished Ward : Terriers And Amersham Hill Officer : Stephanie Penney Level : Delegated Decision 2 19/05527/LBC Received on 29.03.19 Target Date for Determination: 24.05.2019 Other Auth. Ref: Terriers Lodge New Cottage Location : Terriers Lodge Amersham Road -

Historical Notes, Timeline and Previous Occupants of Upper Goddards Farm, Skirmett December 2020

1 Historical Notes, Timeline and Previous Occupants of Upper Goddards Farm, Skirmett December 2020 (v13) 2 Historic England Listing for Upper Goddards Farm (UGF)1: The listing is Grade II and the details are summarised as follows: House, C17, altered and refronted C18 – C19 and C20. Rear has lower walls of flint with timber framing and whitewashed brick infill above. Front rebuilt in brick at various dates. Old tile roof, chimney of thin brick between the right bays, another brick chimney to rear. C19 gabled flint and brick projection to front. Floorplan of Existing Main Building: Origin of Name: Goddard is an ancient Norman name that arrived in England after the Norman Conquest of 1066. Variants exist in France, Holland and Germany 2. Why it was originally used for Upper & Lower Goddards is not known. The HE website gives 275 listed buildings in England using the name Goddards. Early Records Used: We have identified records at The National Archives (TNA) referring to ‘Goddards’ going back to litigation in the mid-1500’s. Again in the early 1600’s certain Deeds refer to ‘the ancient farm of Goddards Farm’. The earliest formal parish registers date from 1538 after the split from Rome and local registers at Hambleden date from shortly that time. However addresses are not normally included. Wills if made can be very informative and may well include addresses and family relationships. After 1838 civil registration records are available and from 1841 census details with addresses can be consulted. The latest census available is for 1911. A range of genealogical sources have also been consulted. -

The Buckinghamshire County Council Speed Limit Review (Various Roads, Various Parishes in Area 8) (30 Mph Speed Limit) Order 200

THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL SPEED LIMIT REVIEW (VARIOUS ROADS, VARIOUS PARISHES IN AREA 8) (30 MPH SPEED LIMIT) ORDER 200 Notice is hereby given that Buckinghamshire County Council proposes to make an Order under the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984. The effect of the Order will be to impose a 30 miles per hour speed restriction on the lengths of road specified in the Schedule below. This Order provides for the revocation of:- “The Buckinghamshire County Council (40mph speed limit) (No. 5) Order, 1987” “The Chepping Wycombe (Built up areas) Order, 1938” “The Buckinghamshire County Council (40mph speed limit) (No. 1) Order, 1978” “Statutory Instrument 1960 No. 2462 Road Traffic and Vehicles. The Trunk Roads (Restricted Roads) (No. 10) Order, 1960” “Statutory Instrument 1971 No. 277 Road Traffic and Vehicles. The Trunk Roads (40mph speed limit) (No. 5) Order, 1971” “The Buckinghamshire County Council (Built up areas) (No. 1) Order, 1957” “The County of Buckingham (40mph speed limit) (No. 6) Order, 1966” “The Buckinghamshire County Council (Restricted Roads) (No. 10) Order, 1973” “The Buckinghamshire County Council (A40 and C97 Ibstone Road, Stokenchurch) (40mph Speed Limit) Order, 2001” “The County of Buckingham (40mph speed limit) (No. 1) Order, 1965” and all extant speed limit orders relating to the A40 West Wycombe Road, from a point 153 metres east of its junction with Church Lane to a point 214 metres west of its junction with Chapel Lane. A copy of the Order and maps showing the lengths of road referred to, together with the Statement of Reasons for proposing to make the Order may be inspected during normal office hours at County Hall, Aylesbury and during normal opening hours at the following libraries: - Stokenchurch Library, Wycombe Road, Stokenchurch, High Wycombe. -

The Old Crown, Bolter End Lane, Wheeler End, Buckinghamshire

The Old Crown, Bolter End Lane, Wheeler End, Buckinghamshire HP14 3NE O.I.E.O.£800,000 A 4 Bed Character Property Offering Superb Views over Common Land in a Semi-Rural Location Freehold The Property The Old Crown is a property of great character built in 1840 from Bucks flint originally being a Public House until approx. 1940. Much character is retained and there is great scope to extend to the rear elevation (Subject to Planning Permission & Local Authority Regulation). The property enjoys a semi-rural location with superb panoramic views across the Common and is in easy distance of Henley-on- Thames, Marlow and High Wycombe. Viewings are highly recommended. Accommodation Comprises:- Ground Floor Door to: Entrance Hall: Wood block flooring with access to tanked cellar. Bedroom: Fitted wardrobes to one wall, radiator, cupboard housing hot water cylinder. Ground Floor Bathroom: Comprising a three piece suite of panel enclosed bath, antique style mixer tap and shower attachment. Further wall mounted thermostatic shower, wash hand basin set into a Victorian style vanity unit with cupboards under, close coupled W.C., plumbing for washing machine, further cupboards housing the central heating boiler and water softener. Sitting Room: A superb room with vaulted ceiling and overlooking the Rear Garden. A key focal point of this room is the stock brick fireplace with inset wood burning stove. French doors give access to the Rear Garden, two separate staircases give access to the Master Bedroom and Bedroom Four. Kitchen/Breakfast Room: A well proportioned Farmhouse style kitchen fitted with a comprehensive range of base and eye level cabinets with roll-edged counter tops over and with dining area. -

Records of Buckinghamshire

RECORDS OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE VOLUME XVII . PART 3 • 1963 RECORDS OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE BEING THE JOURNAL OF THE ARCHITECTURAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY FOR THE COUNTY OF BUCKINGHAM Edited by E. CLIVE ROUSE, F.S.A ELLIOTT VINEY VOLUME XVII. PART 3 1963 PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE SOCIETY BY THE SIDNEY PRESS LTD BEDFORD © Bucks. Archaeological Society* 1964, ARCHAEOLOGICAL NOTES FROM THE COUNTY MUSEUM IT has been agreed that in future a list will be published each year in the Records of archaeological finds which have been brought to the attention of the County Museum in the preceding year. This is a list of all finds recorded in 1963 and, unless otherwise stated, they were actually made in that year. Where a number is given in brackets at the end of an entry the material concerned has been given to the County Museum and has this accession number. Grateful acknowledgments are due to finders and to the Secretaries and members of Societies in the County for supplying information. Amersham, Station Road A sestertius of Commodus was found when digging a trench some years before the last war. Reported by Dr. K. P. Oakley. Approx. NGR SU964972 (74.63) Aylesbury, Elsinore House, 43 Buckingham Street Two jugs, three cooking pots and sherds of the thirteenth to fourteenth century were recovered from a well found when digging foundations for an office block. NGR SP819140 (3.63) Aylesbury, 3 Market Street A fifteenth-century jug was found when digging for foundations and reported by Mr. G. Edwards to be from a pit or ditch. (10.64) Four chamber pots and a saltglazed stoneware bottle of the eighteenth century were found in a cess-pit, formerly a well, when digging for foundations. -

The '69 Hill' Cycle Challenge

The The‘69 Hill‘ ‘69CycleThe Hill’ Challenge‘69 CycleHill‘ Cyclechallenge Challenge Compiled by John Laker. Brought to you by Saddle Safari. 1 1 Local Bike Events 2019 Sat 27th April - Ridgeway Rouleur, take your pick from 30, 55 and 93 mile routes. www.ukcyclingevents.co.uk Join us on Sun 12th May - Bucks off Road Sportive– routes from 40, 80 and 120km Facebook, www.bucksoffroad.co.uk Twitter & Instagram Sat 25th May— Woman vs Cancer ride the night. Ladies only riding through the night with start and finish in Windsor– 100km www.breastcancercare.org.uk Sun 2nd June– Chiltern Valley Sportive– starting from Hambleden’s Chiltern valley winery– ride 37 or 70 mile pint ride www.chilternvalley.co.uk Sat 29th June– Chiltern Samaritan ride– 25,50 and 80 mile route hosted by High Wycombe CC. All proceeds going to www.samaritancycle.com Sun 14th July - Chiltern 100 cycling festival– lots of routes combined with vintage cy- cling festival and live entertainment www.chilterncyclingfestival.com 13th/14th July—Wallingford festival of cycling 50-110km routes plus loads of cyclin related fun www.wallingfordfestivalofcycling.co.uk Sun 20th July– Chilterns white road classic- Italy's Strade Bianche race comes to the Chilterns– 80km with 25km on the ridgeways finest chalk roads www.cycleclassics.co.uk Sun 11th Aug– Reading Roubaix Classic– 100km or 100 miles featuring 13 cobbled sec- tors and ending in the Palmer Park Velodrome www.cycleclassics.co.uk/reading-roubaix Sun 1st sept - Marlow Red Kite Ride. Starts and finishes in Marlow with 3 different routes to choose from. -

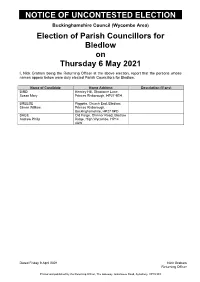

Wyc Parish Uncontested Election Notice 2021

NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Buckinghamshire Council (Wycombe Area) Election of Parish Councillors for Bledlow on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Nick Graham being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bledlow. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BIRD Hemley Hill, Shootacre Lane, Susan Mary Princes Risborough, HP27 9EH BREESE Piggotts, Church End, Bledlow, Simon William Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire, HP27 9PD SAGE Old Forge, Chinnor Road, Bledlow Andrew Philip Ridge, High Wycombe, HP14 4AW Dated Friday 9 April 2021 Nick Graham Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, The Gateway, Gatehouse Road, Aylesbury, HP19 8FF NOTICE OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Buckinghamshire Council (Wycombe Area) Election of Parish Councillors for Bourne End on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Nick Graham being the Returning Officer at the above election, report that the persons whose names appear below were duly elected Parish Councillors for Bourne End. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) APPLEYARD Wooburn Lodge, Grange Drive Mike (Off Brookbank), Wooburn, Bucks, HP10 0QB BINGHAM 7 Jeffries Court, Bourne End, SL8 Timothy Rory 5DY BLAZEY Wyvern, Cores End Road, Bourne Ian Gavin End, Buckinghamshire, SL8 5HR BLAZEY Wyevern, Cores End Road, Miriam Bourne End, Buckinghamshire, SL8 5HR CHALMERS Ivybridge, The Drive, Bourne End, Ben Buckinghamshire, SL8 5RE COBDEN (address in Buckinghamshire) Andrew George MARSHALL Broome House,