Tabla, As a Way of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smt. Kala Ramnath Concert

presents in association with UC Worldfest 2009 ART at its best Internationally Renowned Hindustani Violinis Smt. Kala Ramnath accompanied by Shri Prithwiraj Bhattacharjee on Tabla Date: 25 th April, 2009 (Saturday) Venue: 4400 Aronoff (DAAP Auditorium) Time: 6 :00 pm Parking: Langsam Garage Artiste Biography Maestro KALA RAMNATH , the contemporary torch bearer of the Mewati Gharana, stands today Prithwiraj Bhattacharjee another young and amongst the most outstanding instrumental musicians in the North Indian classical genre. Born upcoming artist began his initial training under into a family of prodigious musical talent, which his guru Dhiranjan Chakraborty at the tender has given Indian music such violin legends as Prof. age of seven. In the year 1994 his life long T.N. Krishnan and Dr. N. Rajam, Kala's genius with the violin manifested itself from childhood. She ambition of learning under the tabla maestro began playing the violin at the tender age of three Ustad Alla Rakha and Ustad Zakir Hussain came under the strict tutelage of her grandfather true. Blessed with highly cultivated fingers, Vidwan. Narayan Aiyar. Simultaneously she received training from her aunt Dr. Smt. N. Rajam. absorbing all the aspects of his guru’s style For fifteen years she put herself under the training through vigorous riyaz under the ever watchful of Mewati vocal maestro, Sangeet Martand Pandit eyes of his guru have made him progress into a Jasraj. This has brought a rare vocal emotionalism to her art. Kala's violin playing is characterized by very promising upcoming tabla player. Prithwi an immaculate bowing and fingering technique, has performed in many solo concerts and command over all aspects of laya, richness and travelled extensively all over India and abroad clarity in sur. -

(Dr) Utpal K Banerjee

About the Book IGNCA is a treasure-trove of cultural artifacts including a rich repository of Video documentaries (published) and Audio and Video DVDs (unpublished). This book – based on the author’s two-year project -- envisions an on-line A-V cultural archive KALASAMPADA that consists of A-V materials stored at IGNCA for the categories of: Interviews; Ritual Documentation; Archaeological Sites and Walk-through; Events; Festivals; Performances (music-dance-theatre-puppetry-mime); Lectures; Seminars; and Workshops. In order to make such a wide variety of materials available on-line – initially on the Intranet, subsequently on a potential Extranet, and eventually (although very selectively) on the Internet – the following digitisation road-map is observed in the project: Conversion of primary A-V materials from analogue to digital format; Creation of data sheets for metadata tagging, following the international standard of Dublin Core Metadata Element Set (DCMES); Integration of metadata with primary A-V material in IGNCA’s Intranet; Access and retrieval by “simple search” with keywords for casual browsers and “advanced search” for users, researchers and scholars with reference to groups of keywords from the intranet. The objectives of the project of on-line A-V cultural archive are: to bring it into public domain; to make it inter-active for scholars; and to make it internationally compatible. Basic advantages of such a project are really five-fold. First, a digital A-V archive assures the near permanent durability of the A-V material. Secondly, it allows need-based quality enhancement. Thirdly, an archive of this kind makes room for highly economic storage of vulnerable Audio and Video files. -

9312 India Power 2.1.Indd

INDIA: A RISING POWER Dr V Nilakant, Associate Professor Department of Management University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand July 2006 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 02 INDIA: A PROFILE 04 GEOGRAPHY 04 PEOPLE 04 CULTURE AND HISTORY 05 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 07 HISTORY AND GROWTH 07 INDIAN ECONOMY 08 INDIA AS A REGIONAL POWER 11 INDIA: CHALLENGES AHEAD 16 INDIA: OPPORTUNITIES 18 CONCLUSION 20 APPENDIX 1: BRIEF PROFILE OF INDIA 21 ISBN-13: 978-0-473-11412-1 ISBN-10: 0-473-11412-7 INDIA: A RISING POWER Dr V Nilakant “From a distance, India often appears as a kaleidoscope of competing, perhaps superficial, images. Is it atomic weapons, or ahimsa? A land struggling against poverty and inequality, or the world’s largest middle-class society? Is it still simmering with communal tensions, or history’s most successful melting pot? Is it Bollywood or Satyajit Ray? Swetta Chetty or Alla Rakha? Is it the handloom or the hyperlink?” US President Bill Clinton in an address to the joint session of the Indian Parliament New Delhi, India, 22 March 2000 INDIA: A RISING POWER 01 INTRODUCTION IN LATE MAY 2005, the President of India, A P J Abdul Kalam, was on a state visit to Switzerland. Reportedly, he surprised his Swiss counterpart, Samuel Schmid, by offering him a gift. In itself this was not an unusual incident. It is, after all, expected from the head of state of a developing country like India to bear traditional gifts that reflect its rich and ancient civilization. What made this incident unusual was the nature of the gift. -

Stephen M. Slawek Curriculum Vitae

Stephen M. Slawek Curriculum Vitae 10008 Sausalito Drive Butler School of Music Austin, TX 78759-6106 The University of Texas at Austin (512) 794-2981 Austin, TX. 78712-0435 (512) 471-0671 Education 1986 Ph.D. (Ethnomusicology) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1978 M.A. (Ethnomusicology) University of Hawaii at Manoa 1976 M. Mus. (Sitar) Banaras Hindu University 1974 B. Mus. (Sitar) Banaras Hindu University 1973 Diploma (Tabla) Banaras Hindu University 1971 B.A. (Biology) University of Pennsylvania Employment 1999-present Professor of Ethnomusicology, The University of Texas at Austin 2000 Visiting Professor, Rice University, Hanzsen and Lovett College 1989-1999 Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin 1985-1989 Assistant Professor of Ethnomusicology and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin 1983-1985 Instructor of Ethnomusicology and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin 1983 Visiting Lecturer of Ethnomusicology, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign 1982 Graduate Assistant, School of Music, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign 1978-1980 Archivist, Archives of Ethnomusicology, School of Music, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Scholarship and Creative Activities Books under contract The Classical Music of India: Going Global with Ravi Shankar. New York and London: Routledge Press. 1997 Musical Instruments of North India: Eighteenth Century Portraits by Baltazard Solvyns. Delhi: Manohar Publishers. Pp. i-vi and 1-153. (with Robert L. Hardgrave) SLAWEK- curriculum vitae 2 1987 Sitar Technique in Nibaddh Forms. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, Indological Publishers and Booksellers. Pp. i-xix and 1-232. Articles in scholarly journals 1996 In Raga, in Tala, Out of Culture?: Problems and Prospects of a Hindustani Musical Transplant in Central Texas. -

Memorandum to Forest Advisory Committee

Memorandum to Forest Advisory Committee (FAC), Urging Rejection of the Etalin Hydro-Electric Project Proposal in Dibang Valley, Arunachal Pradesh (RO/Ministry File Number F. No. 8-20/2014-FC) By 4300+ Concerned Citizens Email: [email protected] Web: www.conservationindia.org April 28, 2020 To Directory General of Forests Chairman, Forest Advisory Committee, [email protected] To Additional Director General of Forests (Forest Conservation) Member, Forest Advisory Committee, [email protected] To Inspector General of Forests (Forest Conservation) Member Secretary, Forest Advisory Committee, [email protected] To Shri. Suramya Vora Member, Forest Advisory Committee, [email protected] To Dr. Kaushal Rajesh Non-official Member, Forest Advisory Committee, [email protected] Sirs, Sub: Public campaign seeking rejection of the Etalin Hydro-Electric Project in Arunachal Pradesh’s Dibang Valley (RO/Ministry File Number F. No. 8-20/2014-FC) Conservation India - India's largest online forum for wildlife conservation - ran a campaign on its website seeking support for the memorandum being submitted to your committee for its urgent and kind consideration, urging you to reject the Etalin Hydro-Electric Project in Arunachal Pradesh’s Dibang Valley. You can view the memorandum’s content and the names of its signatories in subsequent pages below. In less than 3 days, the campaign attracted over 4300 signatures. Dibang Valley in Arunachal Pradesh is home to a genetically distinct population of tigers, 75+ species of other mammals, and 300+ species of birds, including many endangered ones unique to the region. The valley is part of the Eastern Himalaya Global Biodiversity Hotspot, which is one of only 36 biodiversity hotspots in the world. -

B.A./B.Sc. (12+3 SYSTEM of EDUCATION) (Semester–VI)

SYLLABUS FOR B.A./B.Sc. (12+3 SYSTEM OF EDUCATION) (Semester–VI) Examinations: 2019–20 GURU NANAK DEV UNIVERSITY AMRITSAR Note: (i) Copy rights are reserved. Nobody is allowed to print it in any form. Defaulters will be prosecuted. (ii) Subject to change in the syllabi at any time. Please visit the University website time to time. 1 B.A./B.Sc. (Semester System) (12+3 System of Education) (Semester–VI) (Session 2019-20) INDEX OF SEMESTER–VI Sr.No. Subject Page No. FACULTY OF ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES 1. Political Science 5-6 2. History 7 3. Journalism and Mass Communication (Vocational) 8 4. Mass Communication and Video Production (Vocational) 9-10 5. Sociology 11 6. Psychology 12-14 7. Women Empowerment 15 8. Defence and Strategic Studies 16-18 9. Geography 19-22 10. Public Administration 23 FACULTY OF ECONOMICS & BUSINESS 11. Office Management and Secretarial Practice (Vocational) 24-27 12. Travel and Tourism 28-30 13. Tourism and Hotel Management (Vocational) 31-32 14. Tax Procedure and Practices (Vocational) 33-37 15. Advertising Sales Promotion and Sales Management (Vocational) 38-39 16. Commerce 40 17. Tourism and Travel Management (Vocational) 41-42 18. Economics 43 19. Industrial Economics 44 20. Quantitative Techniques 45 21. Agricultural Economics and Marketing 46 22. Rural Development 47-48 2 B.A./B.Sc. (Semester System) (12+3 System of Education) (Semester–VI) (Session 2019-20) FACULTY OF SCIENCES 23. Mathematics 49-50 24. Statistics 51-53 25. Chemistry 54-59 26. Physics 60-62 27. Home Science 63-65 28. Cosmetology (Vocational) 66-67 29. -

Oct 2014-May 2015 SIVANANDA Ashram Yoga Retreat BAHAMAS

SIVANANDA Ashram Yoga Retreat BAHAMAS SIVANANDA Ashram Yoga Retreat BAHAMAS Expand your horizons . Yoga Vacations | Teacher Training | Experiential Courses Oct 2014-May 2015 SIVANANDA Ashram Yoga Retreat BAHAMAS October 2014—May 2015 Located on Paradise Island on one of the finest beaches in the world, the Sivananda Ashram Yoga Retreat Bahamas is a true oasis of calm and natural beauty, and offers a unique combination of a traditional ashram and a modern yoga retreat. Welcome 2 Welcome 3 Our Lineage 5 Ways to Visit 6 At the Ashram Getting started 9 Yoga Vacation Program 11 The Well Being Center 13 Sivananda Yoga Teacher Training Course 15 Advanced Yoga Teacher Training Course 17 Programs with Swami Swaroopananda 18 Sivananda Core Courses Explore 22 Calendar of October to May Programs Deepen 105 Professional Accreditation and Continuing Education 106 Residential Study/Karma Yoga Useful info 108 Plan Your Visit 110 Registration and Rates 112 Teacher and Presenter Index 114 Program Guide sivanandabahamas.org | 1 Welcome from Swami Swaroopananda Welcome. It is with great pleasure that I invite you to join us in the Bahamas this year for another season of joy, beauty, and wisdom and the profound teachings of yoga given to us by our teacher, Swami Vishnudevananda and his teacher, Swami Sivananda. Now more than ever, the world needs the knowledge that yoga offers. We are in the midst of a spiritual revolution, and it is my belief that in 50 years we will not recognize this planet as changes are happening fast. Engagement with spiritual disciplines, including yoga and meditation, is key for navigating this time of transition and creating a more peaceful future. -

CURRICULUM – VITAE [email protected]

CURRICULUM – VITAE [email protected] DR. PAMIL MODI A VERSATILE SINGER AND PERFORMER Assistant Professor Dept. of Music M.L.S. University, Udaipur Educational Qualifications Degrees Year Board/University SET 2015 RPSC, Ajmer Ph.D. 2009 Mohan Lal Sukhadia University, Udaipur M.A. Music (Vocal) 2004 Mohan Lal Sukhadia University, Udaipur Sangeet Alankar 2003 Surnanandan Bharti-Kolkotta M.A. Music (Alankar) 2001 Akhil Bhartiya Gandharv Mahavidhyalya Mandal-Mumbai B.A. 2002 Mohan Lal Sukhadia University, Udaipur (Music,Eng.Lit, Geog.) Teaching Experience Presently working in the Department of Music as Assistant Professor, MLSU, Udaipur. Teaching experience in the Department of Music as a Lecturer in Aishwarya College for 2 years, (2008 to 2010). Had been associated with Mohan Lal Sukhadia University as a Guest Faculty in Dept. of Music for past 12 years, (2006 – 2018). Training and Teaching to students in Hindustani Vocal Classical Music of various age groups under the Organisation, Maharana Kumbha Sangeet Parishad. Worked as a Resource Person for Vocal Music Training in PIE, Rajasthan Patrika, Udaipur, 2004. Awards / Appreciations Bhaskar Woman of The Year Award-2019 by Deputy Chief Minister Sachin Pilot Jaipur. Woman of Substance by Big FM 92.7 and Aravli Foundation in 2019, Udaipur. Excellency Certificate by Ghazal Academy, Udaipur and Maharana Kumbha Sangeet Parishad, Udaipur, towards Music, July 2018. Received Gold Medal from Governor for Standing First in order of Merit in Music, in 2005. Awarded on International Women's Day in “Chingari Utsav” for contribution in Indian Classical Music by Rotary Club, Udaipur, 2016. Awarded by His Highness Maharana Arvind Singh Ji Mewar of Udaipur for excellent performance of Indian Classical Vocal Music on Guru Purnima, 2004. -

MUSIC (Lkaxhr) 1. the Sound Used for Music Is Technically Known As (A) Anahat Nada (B) Rava (C) Ahat Nada (D) All of the Above

MUSIC (Lkaxhr) 1. The sound used for music is technically known as (a) Anahat nada (b) Rava (c) Ahat nada (d) All of the above 2. Experiment ‘Sarna Chatushtai’ was done to prove (a) Swara (b) Gram (c) Moorchhana (d) Shruti 3. How many Grams are mentioned by Bharat ? (a) Three (b) Two (c) Four (d) One 4. What are Udatt-Anudatt ? (a) Giti (b) Raga (c) Jati (d) Swara 5. Who defined the Raga for the first time ? (a) Bharat (b) Matang (c) Sharangdeva (d) Narad 6. For which ‘Jhumra Tala’ is used ? (a) Khyal (b) Tappa (c) Dhrupad (d) Thumri 7. Which pair of tala has similar number of Beats and Vibhagas ? (a) Jhaptala – Sultala (b) Adachartala – Deepchandi (c) Kaharva – Dadra (d) Teentala – Jattala 8. What layakari is made when one cycle of Jhaptala is played in to one cycle of Kaharva tala ? (a) Aad (b) Kuaad (c) Biaad (d) Tigun 9. How many leger lines are there in Staff notation ? (a) Five (b) Three (c) Seven (d) Six 10. How many beats are there in Dhruv Tala of Tisra Jati in Carnatak Tala System ? (a) Thirteen (b) Ten (c) Nine (d) Eleven 11. From which matra (beat) Maseetkhani Gat starts ? (a) Seventh (b) Ninth (c) Thirteenth (d) Twelfth Series-A 2 SPU-12 1. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 2. ‘ ’ ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 3. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 4. - ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 5. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 6. ‘ ’ ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 7. ? (a) – (b) – (c) – (d) – 8. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 9. ? (a) (b) (c) (d) 10. -

Raag-Mala Music Society of Toronto: Concert History*

RAAG-MALA MUSIC SOCIETY OF TORONTO: CONCERT HISTORY* 2013 2012 2011 Praveen Sheolikar, Violin Ud. Shahid Parvez, Sitar Pt. Balmurli Krishna, Vocal Gurinder Singh, Tabla Subhajyoti Guha, Tabla Pt. Ronu Majumdar, Flute Arati Ankalikar Tikekar, Vocal Ud. Shujaat Khan, Sitar Kishore Kulkarni, Tabla Abhiman Kaushal, Tabla Ud. Shujaat Khan, Sitar Abhiman Kaushal, Tabla Anand Bhate, Vocal Vinayak Phatak, Vocal Bharat Kamat, Tabla Enakshi, Odissi Dance The Calcutta Quartet, Violin, Suyog Kundalka, Harmonium Tabla & Mridangam Milind Tulankar, Jaltrang Hidayat Husain Khan, Sitar Harvinder Sharma, Sitar Vineet Vyas, Tabla Ramdas Palsule, Tabla Warren Senders, Lecture- Raja Bhattacharya, Sarod Demonstration and Vocal Shawn Mativetsky, Tabla Raya Bidaye, Harmoium Ravi Naimpally, Tabla Gauri Guha, Vocal Ashok Dutta, Tabla Luna Guha, Harmonium Alam Khan, Sarod Hindole Majumdar, Tabla Sandipan Samajpati, Vocal Raya Bidaye, Harmonium Hindole Majumdar, Tabla Ruchira Panda, Vocal Pandit Samar Saha, Tabla Anirban Chakrabarty, Harmonium 2010 2009 2008 Smt. Ashwini Bhide Deshpande, Smt. Padma Talwalkar, Vocal Pt. Vishwa Mohan Bhatt, Mohan Vocal Rasika Vartak, Vocal Veena Vishwanath Shirodkar, Tabla Utpal Dutta, Tabla Subhen Chatterji, Tabla Smt. Seema Shirodkar, Suyog Kundalkar, Harmonium Heather Mulla, Tanpura Harmonium Anita Basu, Tanpura Milind Tulankar, Jaltarang Pt. Rajan Mishra, Vocal Sunit Avchat, Bansuri Pt. Sajan Mishra, Vocal Tejendra Majumdar, Sarod Ramdas Palsule, Tabla Subhen Chatterji, Tabla Abhijit Banerjee,Tabla Sanatan Goswami, Harmonium Kiran Morarji, Tanpura Irshad Khan, Sitar Manu Pal, Tanpura Subhojyoti Guha, Tabla Aparna Bhattacharji, Tanpura Aditya Verma, Sarod Ramneek Singh, Vocal Hindol Majumdar, Tabla Pt. Ronu Majumdar, Flute Won Joung Jin, Kathak Ramdas Palsule, Tabla Amaan Ali Khan, Sarod Rhythm Riders, Tabla Bharati, tanpura Ayaan Ali Khan, Sarod Vineet Vyas, Tabla 1 RAAG-MALA MUSIC SOCIETY OF TORONTO: CONCERT HISTORY* 2010 Cont. -

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2020 (PAGE 4) PERSONALITY MOVIE-REVIEW Tributes to Tabla maestro SHIKARA Ravi Rohmetra Ustad Allah Rakha A potboiler that uses KP Exodus only as a backdrop Khan, the country's Leading Tabla Exponet Ravinder Kaul refuse to show any perceptible sign of was born on 29th April aging. The only characters in the film who 1919 at Phagwal It has been 30 years since 4 lakh Kash- look quite genuine and authentic are the Village of Dist. miri Pandits were forced to leave their 4000 Kashmiri Pandit refugees, who SAMBA, Jammu in a centuries old place of habitat, in the wake form the crowds in the refugee camps in of armed Islamic insurgency, to live a mis- Punjabi Gharana. His Jammu. erable life in torn tents and ramshackle The background music has been com- mother tongue was rooms, away from their homes in the pris- posed by AR Rahman and Qutub-e-Kirpa, Dogri. He became fas- tine beautiful valley of Kashmir. The while the songs have been composed by cinated with the sound tragedy of the victims of the biggest Abhay Rustam Sopori and Sandesh and rhythm of the migration in India since independence Shandilya. The Chhakari song 'Shukrana tabla at the age of 12 got further aggravated when no main- Gul Khiley', composed by Abhay Rustam stream political party and no human years. He used to be Sopori, written by Bashir Arif and sung by rights or social organization took any fascinated by the Munir Meer, and the strains of Santoor in notice of their sufferings. -

Bio-Data and Current Research Work of Zahoor Ahmed

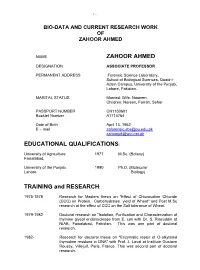

1 - BIO-DATA AND CURRENT RESEARCH WORK OF ZAHOOR AHMED NAME ZAHOOR AHMED DESIGNATION ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR PERMANENT ADDRESS Forensic Science Laboratory, School of Biological Sciences, Quaid-i- Azam Campus, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan. MARITAL STATUS Married: Wife: Naseem, Children: Noreen, Farrah, Sehar PASSPORT NUMBER CN1150601 Booklet Number A1714764 Date of Birth April 13, 1952 E – mail [email protected] [email protected] EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS: University of Agriculture 1977 M.Sc. (Botany) Faisalabad. University of the Punjab, 1990 Ph.D. (Molecular Lahore. Biology) TRAINING and RESEARCH: 1975-1978 Research for Masters thesis on "Effect of Chlorocoline Chloride (CCC) on Protein. Carbohydrates yield of Wheat" and Post M.Sc research at the effect of CCC on the Salt tolerance of Wheat. 1979-1982 Doctoral research on "Isolation, Purification and Characterization of thymine glycol endonuclease from E. coli with Dr. S. Riazuddin at NIAB, Faisalabad, Pakistan. This was one part of doctoral research. 1982- Research for doctoral thesis on "Enzymatic repair of O-alkylated thymidine residues in DNA" with Prof. J. Laval at Institute Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, Paris, France. This was second part of doctoral research. 2 - 1983- Training on the purification of restriction endonucleases from different microorganisms, in Dr. R. J. Roberts Lab., at Cold Spring Harbor Labs., NY. USA. 1983-1985 Research on "The Purification of Restriction Endonucleases from different bacterial strains" at the Centre for Advanced Molecular Biology, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan. 1986-1987 Post Doctoral research on "The genetic manipulation of hydrocarbon biodegradation" with Prof. S. Riazuddin at Centre for Advanced Molecular Biology, University of the Punjab, Lahore.