Warfarin-Induced Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Table Summarizes Changes to the HF Qxq As of 10/11/2019 Question

Updated HFS Instructions (QxQs) This table summarizes changes to the HF QxQ as of 10/11/2019 Question in HF QxQ Description of Changes in HF QXQ General Instructions, pg. 3 Clarification added to rules for history Q29.d.10., pg. 40 Clarification made on how to record pulmonary hypertention Q29.d.14., pg. 41 Clarification made on how to record diastolic dysfunction Q42., pg. 42 Clarification made on how to record troponin I Section VII: Medication, pg. 54 Clarificaiton made on how to record medications Appendix A, pg. 61 Updated list of medications Edoxaban (ACOAG, Generic) Lixiana (ACOAG, Trade) Prexxartan (ARB, Trade) INSTRUCTIONS FOR COMPLETING HEART FAILURE HOSPITAL RECORD ABSTRACTION FORM HFS Version C, 10/1/2015 HFA Version D, 10/1/2015 HF QxQ, 10/11/2019 Table of Contents Page General Instructions……………………………………………………………….. 2 Specific Items………………………………………………………………………. 3 Section l: Screening for Decompensation………………………………….. 5 Section ll: History of Heart Failure…………………………………………... 10 Section lll: Medical History ………………………………………………….. 13 Section lV: Physical Exam - Vital Signs…………………………………….. 24 Section V: Physical Exam - Findings……………………………………….. 26 Section Vl: Diagnostic Tests…………………………………………………. 31 Section Vll: Biochemical Analyses………………………………………….. 48 Section Vlll: Interventions…………………………………………………….. 51 Section lX: Medications………………………………………………………. 54 Section X: Complications Following Events………………………………… 59 Section Xl: Administrative……………………………………………………. 60 Appendix A: ARIC Heart Failure/Cardiac Drugs: ………………………………. 61 Alphabetical Sort Appendix B: Potential Scenarios of the Onset of Heart………………………. 73 Failure Event or Decompensation HF QxQ 10/11/2019 Page 1 of 73 General Instructions The HFAA form was initially used for all discharges selected for HF surveillance. It was replaced by the HFAB and HFSA forms and then updated June 2012 with HFAC and HFSB. -

MIRADON FPO Brand of Anisindione Tablets

R 1 2 3 4 5 3 4 F-16099775 1898 ® MIRADON FPO brand of anisindione Tablets DESCRIPTION MIRADON Tablets contain a syn- thetic anticoagulant, anisindione, an indanedione derivative. Each tablet contains 50 mg anisin- dione. They also contain: corn starch, FD&C Red No. 3, gelatin, lactose, and hydrogenated cotton- seed oil. ACTIONS Like phenindione, to which it is re- lated chemically, anisindione exercises its thera- peutic action by reducing the prothrombin activity of the blood. INDICATIONS Anisindione is indicated for the prophylaxis and treatment of venous thrombosis and its extension, the treatment of atrial fibrilla- tion with embolization, the prophylaxis and treat- ment of pulmonary embolism, and as an adjunct in the treatment of coronary occlusion. CONTRAINDICATIONS All contraindications to oral anticoagulant therapy are relative rather than absolute. Contraindications should be evaluated for each patient, giving consideration to the need for and the benefits to be achieved by anticoagu- lant therapy, the potential dangers of hemor- rhage, the expected duration of therapy, and the quality of patient monitoring and compliance. Hemorrhagic Tendencies or Blood Dyscrasias: In general, oral anticoagulants are contraindi- cated in patients who are bleeding or who have hemorrhagic blood dyscrasias or hemorrhagic tendencies (eg, hemophilia, polycythemia vera, purpura, leukemia) or a history of bleeding dia- thesis. They are contraindicated in patients with recent cerebral hemorrhage, active ulceration of the gastrointestinal tract, including ulcerative colitis, or open ulcerative, traumatic, or surgical wounds. Oral anticoagulants may be contraindi- cated in patients with recent or contemplated brain, eye, or spinal cord surgery or prostatec- tomy, and in those undergoing regional or lumbar block anesthesia or continuous tube drainage of the small intestine. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0005722 A1 Jennings-Spring (43) Pub

US 20090005722A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0005722 A1 Jennings-Spring (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 1, 2009 (54) SKIN-CONTACTING-ADHESIVE FREE Publication Classification DRESSING (51) Int. Cl. Inventor: Barbara Jennings-Spring, Jupiter, A61N L/30 (2006.01) (76) A6F I3/00 (2006.01) FL (US) A6IL I5/00 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: AOIG 7/06 (2006.01) Irving M. Fishman AOIG 7/04 (2006.01) c/o Cohen, Tauber, Spievack and Wagner (52) U.S. Cl. .................. 604/20: 602/43: 602/48; 4771.5; Suite 2400, 420 Lexington Avenue 47/13 New York, NY 10170 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 12/231,104 A dressing having a flexible sleeve shaped to accommodate a Substantially cylindrical body portion, the sleeve having a (22) Filed: Aug. 29, 2008 lining which is substantially non-adherent to the body part being bandaged and having a peripheral securement means Related U.S. Application Data which attaches two peripheral portions to each other without (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 1 1/434,689, those portions being circumferentially adhered to the sleeve filed on May 16, 2006. portion. Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2009 Sheet 1 of 9 US 2009/0005722 A1 Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2009 Sheet 2 of 9 US 2009/0005722 A1 10 8 F.G. 5 Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2009 Sheet 3 of 9 US 2009/0005722 A1 13 FIG.6 2 - Y TIII Till "T fift 11 10 FIG.7 8 13 6 - 12 - Timir" "in "in "MINIII. -

Some Aspects of the Pharmacology of Oral Anticoagulants

Some aspects of the pharmacology of oral anticoagulants The pharmacology of oral anticoagulants ls discussed with particular rejerence to data of value in the management of therapy. The importance of individual variability in response and drug interaction is stressed. Other effects of these agents which may have clinical utility are noted. William W. Coon, M.D., and Park W. Willis 111, M.D., Ann Arbor, Mich. The Departments of Surgery (Section of General Surgery) and Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School In the twenty-five years sinee the isola dividual struetural features but by a com tion of the hemorrhagie faetor in spoiled bination of several: molecular shape, in sweet clever," the gradually inereasing creased aetivity with 6 membered hetero utilization of oral antieoagulants for the eyclic rings with a substituent in position prevention and therapy of thromboembolie 8 and with a methoxyl rather than a free disease has made them one of the most hydroxl group. Also important is the dernon widely used groups of pharmacologic stration that levorotatory warfarin is seven agents. This review is restrieted to as times more aetive than its enantiomer.F" peets of the pharmaeology of these agents As Hunter and Shepherd'" have pointed whieh may be important to their proper out, the failure to obtain a precise cor clinieal utilization. relation between strueture and antieoagu lant aetivity is "not surprising in view of Relation of structure to function the influence of small struetural changes The oral antieoagulants have been di on sueh variables as solubility, rate of ab vided into four main groups on the basis sorption, ease of distribution, degree of of ehemieal strueture (Fig. -

Home Medication Form

DIVISION OF EDUCATION • SURGICAL PATIENT EDUCATION Medication and Surgery Inspiring Quality: BEFORE YOUR OPERATION Highest Standards, Better Outcomes Your medications may have to be adjusted before your operation. Some medication can affect your recovery and response to anesthesia. Write down all of the mediations you are taking. A blank medication list is provided if you need it. Make a list. Your list should include: ● Any prescription medications ● Over-the-counter (OTC) medications (such as aspirin or Tylenol) ● Herbs, vitamins, and supplements ● Tell your doctor if you smoke and how often you drink alcohol or use other recreational drugs. Check with your List of medications that affect blood clotting:* doctor about: ● Antiplatelet Medication: Anagrelide (Agrylin®), aspirin (any brand, all doses), cilostazol (Pletal®), clopidogrel (Plavix®), ● When to stop taking all vitamins, dipyradamole (Persantine®), dipyridamole/aspirin (Aggrenox®), herbs, and diet supplements. enteric-coated aspirin (Ecotrin®), ticlopidine (Ticlid®) This could be 10 to 14 days ● ® before and up to 7 days after Anticoagulant Medication: Anisindione (Miradon ), Arixtra, ® your test or operation. enoxaparin (Lovenox ) injection, Fragmin, heparin injection, Pradaxa, pentosan polysulfate (Elmiron®), warfarin (Coumadin®), Xerelto ● How to take your medication on ● the morning of your operation. You Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: Celebrex, diclofenac ® ® ® ® may be instructed to take some (Voltaren , Cataflam ), diflunisal (Dolobid ), etodolac (Lodine ), fenoprofen -

Appendix C Medication Tables

Appendix C Medication Tables Note: The medication tables are not meant to be inclusive lists of all available therapeutic agents. Approved medication tables will be updated regularly. Discrepancies must be reported. See Resource Section of this manual for additional contact information. Release Notes: Aspirin Table Version 1.0 Table 1.1 Aspirin and Aspirin-Containing Medications Acetylsalicylic Acid Acuprin 81 Alka-Seltzer Alka-Seltzer Morning Relief Anacin Arthritis Foundation Aspirin Arthritis Pain Ascriptin Arthritis Pain Formula ASA ASA Baby ASA Baby Chewable ASA Baby Coated ASA Bayer ASA Bayer Children's ASA Buffered ASA Children's ASA EC ASA Enteric Coated ASA/Maalox Ascriptin Aspergum Aspir-10 Aspir-Low Aspir-Lox Aspir-Mox Aspir-Trin Aspirbuf Aspircaf Aspirin Aspirin Baby Aspirin Bayer Aspirin Bayer Children's Aspirin Buffered Aspirin Child Aspirin Child Chewable Aspirin Children's Aspirin EC Aspirin Enteric Coated Specifications Manual for National Appendix C-1 Hospital Quality Measures Table 1.1 Aspirin and Aspirin-Containing Medications (continued) Aspirin Litecoat Aspirin Lo-Dose Aspirin Low Strength Aspirin Tri-Buffered Aspirin, Extended Release Aspirin/butalbital/caffeine Aspirin/caffeine Aspirin/pravachol Aspirin/pravastatin Aspirtab Bayer Aspirin Bayer Aspirin PM Extra Strength Bayer Children’s Bayer EC Bayer Enteric Coated Bayer Low Strength Bayer Plus Buffered ASA Buffered Aspirin Buffered Baby ASA Bufferin Bufferin Arthritis Strength Bufferin Extra Strength Buffex Cama Arthritis Reliever Child’s Aspirin Coated Aspirin -

I ©Copyright 2012 Clara K. Hsia

©Copyright 2012 Clara K. Hsia i Biochemical and Mechanistic Studies of the Interactions Between Vitamin K Antagonists and Vitamin K Epoxide Reductase Clara K. Hsia A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Allan E. Rettie, Chair Kent L. Kunze William M. Atkins Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Medicinal Chemistry University of Washington Abstract Biochemical and Mechanistic Studies of the Interactions Between Vitamin K Antagonists and Vitamin K Epoxide Reductase Clara K. Hsia Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Allan E. Rettie Department of Medicinal Chemistry The studies that are presented in this dissertation have; (i) established a mechanism by which warfarin dose response is modulated by VKORC1 genotype under optimized conditions for kinetic analysis of human vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR) catalytic activity, (ii) evaluated previously suggested irreversible and reversible mechanisms of VKOR inhibition by vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), and (iii) elucidated the role of tyrosine 139 in the catalytic center and inhibitor binding site of VKOR. Firstly, observation of VKOR activity in human liver microsomes (HLMs) under varied experimental conditions demonstrated that human VKOR is a highly labile enzyme. Under optimal conditions, evaluation of genotyped HLMs for downstream effects of altered VKORC1 mRNA expression revealed a relationship between the VKORC1 B haplotype and increased the catalytic activity and protein expression of VKOR. This demonstrates that warfarin dose is regulated through a transcriptional mechanism wherein higher levels of VKORC1 mRNA translate to increased protein expression and associated enzymatic activity of VKOR, thus requiring a higher dose of warfarin to maintain the same target level of anticoagulation. -

Utah Medicaid Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee Drug

Utah Medicaid Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee Drug Class Review Non-Selective Oral Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs AHFS Classification: 28:08.04.92 Other Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents Diclofenac Etodolac Fenoprofen Flurbiprofen Ibuprofen Indomethacin Ketoprofen Ketorolac Mefenamic Acid Meloxicam Nabumetone Naproxen Oxaprozin Piroxicam Sulindac Tolmetin Final Report April 2018 Review prepared by: Elena Martinez Alonso, B.Pharm., Medical Writer Vicki Frydrych, B.Pharm., Pharm.D., Clinical Pharmacist Valerie Gonzales, Pharm.D., Clinical Pharmacist Joanita Lake, B.Pharm., MSc EBHC (Oxon), Research Assistant Professor, Clinical Pharmacist Michelle Fiander, MA, MLIS, Research Assistant Professor, Evidence Synthesis Librarian Joanne LaFleur, PharmD, MSPH, Associate Professor University of Utah College of Pharmacy University of Utah College of Pharmacy, Drug Regimen Review Center Copyright © 2018 by University of Utah College of Pharmacy Salt Lake City, Utah. All rights reserved 1 Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Table 1. FDA-Approved Oral Non-selective NSAIDs......................................................................... 7 Table 2. FDA-Approved Indication for Oral Non-selective NSAIDs ............................................... -

Effectiveness and Safety of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral

Effectiveness and Safety of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants Compared to Vitamin K Antagonists for the Treatment of Ventricular Thrombus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies Qing Yang Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College Fuwai Hospital Liyun He PUMCH: Peking Union Medical College Hospital Yan Liang ( [email protected] ) Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College Fuwai Hospital https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9053-9389 Research Keywords: ventricular thrombus, non-vitamin K antagonists, oral anticoagulants, warfarin Posted Date: December 1st, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-115338/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/21 Abstract Background To compare the effectiveness and safety of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) on the rate of thrombus resolution and clinical outcomes. Method MEDLINE, PUBMED, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, China National Knowledge Infrastructure Database and Wanfang Database, were searched up to August 16, 2020. Observational studies of patients with ventricular thrombus which compared the effect of two agents on the primary outcome were included. The primary outcome was rate of thrombus resolution, and the secondary outcomes were systemic embolism, bleeding and all-cause death. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% condential intervals (CI) were utilized for the pooled results. Result Eight studies with 905 participants were nally included. Among these cases, 66.6% of patients received VKAs and 33.4% of patients received NOACs. Rivaroxaban (71.9%) was the most commonly used NOACs. -

Medications & Supplements to Stop Before Surgery & Injections

Medications & Supplements to Stop Before Surgery & Injections Some medications and dietary supplements can contribute to bruising, bleeding or other problems if taken before injections (Botox, Fillers) or surgery. These must be stopped 2 weeks before! Most of the supplements and drugs below can contribute to coagulation problems (Blood Thinners) and should be stopped 2 weeks before injections or surgery. The asterisk (*) identifies those that could affect anesthesia and healing and relate mostly to surgery. If a medication on the list has been prescribed by your doctor for medical reasons (Plavix, Coumadin, Aspirin for a stent, Prednisone, etc.), DO NOT STOP the medication without first discussing it with your physician. Please let us know if you have been prescribed any of these medications so we can help you formulate a safe plan. The list below is ever changing with new medications and more information on old ones. Therefore, it should not be considered complete. If you are not sure about a product, ask us and we will research it. If you were prescribed Vitamedica Vitamins before surgery, these are safe to use and are designed for the peri- operative period. The doctors will advise you when you can resume supplements and medications after surgery (usually 7 days). ASPIRIN & RELATED Acetyl Salicylic Acid Mesalamine (Asacol, Apriso, Lialda, Pentasa, Canasa) (Anacin, Alka Seltzer, Ascriptin, Bufferin, Bayer, Excedrin, etc) Olsalazine (Dipentum) Aminosalicylic Acid Sodium Salicylate Bismuth Subsalicylate (Pepto Bismol) Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) -

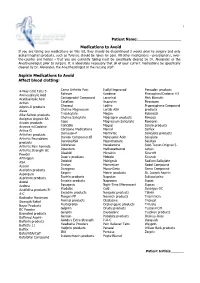

Medications to Avoid

1 Patient Name:___________________ Medications to Avoid If you are taking any medications on this list, they should be discontinued 2 weeks prior to surgery and only acetaminophen products, such as Tylenol, should be taken for pain. All other medications – prescriptions, over- the-counter and herbal – that you are currently taking must be specifically cleared by Dr. Alexander or the Anesthesiologist prior to surgery. It is absolutely necessary that all of your current medications be specifically cleared by Dr. Alexander, the Anesthesiologist or the nursing staff. Aspirin Medications to Avoid Affect blood clotting: 4-Way Cold Tabs 5- Cama Arthritis Pain Isollyl Improved Percodan products Aminosalicylic Acid Reliever Kaodene Phenaphen/Codeine #3 Acetilsalicylic Acid Carisoprodol Compound Lanorinal Pink Bismuth Actron Cataflam lbuprohm Piroxicam Adprin-B products Cheracol Lodine Propoxyphene Compound Aleve Choline Magnesium Lortab ASA products Alka-Seltzer products Trisalicylate Magan Robaxisal Amigesic Argesic-SA Choline Salicylate Magnaprin products Rowasa Anacin products Cope Magnesium Salicylate Roxeprin Anexsia w/Codeine Coricidin Magsal Saleto products Arthra-G Cortisone Medications Marnal Salflex Arthriten products Damason-P Marthritic Salicylate products Arthritis Foundation Darvon Compound-65 Mefenamic Acid Salsalate products Darvon/ASA Meprobamate Salsitab Arthritis Pain Formula Diclofenac Mesalamine Scot-Tussin Original 5- Arthritis Strength BC Dipenturn Methocarbarnol Action Powder Disalcid Micrainin Sine-off Arthropan Doan's -

Synthesis of Novel Indane-1,3-Dione Derivatives and Their Biological Evaluation As Anticoagulant Agents

CROATICA CHEMICA ACTA CCACAA, ISSN 0011-1643, e-ISSN 1334-417X Croat. Chem. Acta 82 (3) (2009) 613–618. CCA-3353 Original Scientific Paper Synthesis of Novel Indane-1,3-dione Derivatives and Their Biological Evaluation as Anticoagulant Agents Katarzyna Mitka,a,* Piotr Kowalski,a Dariusz Pawelec,b Zbigniew Majkab aInstitute of Organic Chemistry and Technology, Cracow University of Technology, 24 Warszawska St., 31-155 Kraków, Poland bPharmaceutical Company Adamed Ltd, Pieńków 149, 05-152 Czosnów, Poland RECEIVED OCTOBER 27, 2006; REVISED JUNE 25, 2008; ACCEPTED JUNE 26, 2008 Abstract. 2-Substituted derivatives of indane-1,3-dione 3a–f , 5a–g, 6a–g were synthesized and investi- gated as anticoagulant agents. 2-Arylindane-1,3-diones (3) were obtained in the reaction of phthalide with appropriate arylaldehydes. 2-Arylmethyleneindane-1,3-diones (5) were prepared by condensation of indane-1,3-dione with the corresponding arylaldehydes. The compounds 5 were converted into their methyl analogues 6 by reduction with sodium tetrahydroborate. All of the compounds studied were screened for the anticoagulant activity. The highest prothrombin time was established for 2-[4-(methyl- sulfanyl)phenyl]indane-1,3-dione (3c) (PT = 33.71 ( 26.01) s), which was very close to PT of the drug anisindione (PT = 36.0 ( 26.42) s). Keywords: indane-1,3-dione, 2-arylindane-1,3-dione, 2-arylmethyleneindane-1,3-dione, 2-arylmethyl- indane-1,3-dione, anticoagulant activity INTRODUCTION advantages. Warfarin acts as an inhibitor of vitamin K epoxide reductase and vitamin