Relationships Between Memory, Justice and Forgiveness with a Focus on Bosnia and Herzegovina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 VIEWS. from the Past: How I Found Myself in War?

FROM THE PAST: HOW I FOUND MYSELF IN WAR TOWARDS THE FUTURE: HOW TO REACH SUSTAINABLE PEACE 44POGLEDPOGLEDAA VLASOTINCE SPEAKERS ON THE PUBLIC FORUMS 24.10.2003. WERE PEOPLE WHO PARTICIPATED IN WARS IN THE REGION OF FORMER YUGOSLAVIA ADNAN HASANBEGOVI] IZ SARAJEVA NOVI SAD DRAGO FRAN^I[KOVI] IZ ZAGREBA 28.10.2003. GORDAN BODOG IZ ZAGREBA KEMAL BUKVI] IZ ZAGREBA KRALJEVO NERMIN KARA^I] IZ SARAJEVA 11.11.2003. NOVICA KOSTI] IZ VLASOTINCA INITIATIVE AND ORGANISATION CENTAR ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU CENTRE FOR NONVIOLENT ACTION Office in Belgrade Office in Sarajevo Studentski trg 8, 11000 Beograd, SCG Radni~ka 104, 71000 Sarajevo, BiH Tel: +381 11 637-603, 637-661 Tel: +387 33 212-919, 267-880 Fax: +381 11 637-603 Fax: +387 33 212-919 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.nenasilje.org IN COOPERATION WITH UDRU@ENJE BORACA RATA 90. VLASOTINCE DRU[TVO ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU from Novi Sad OMLADINSKA ORGANIZACIJA KVART from Kraljevo Publication edited and articles written by activists of Centre for Nonviolent Action Adnan Hasanbegovi} Helena Rill Ivana Franovi} Milan Coli} Humljan Ned`ad Horozovi} Nenad Vukosavljevi} Sanja Deankovi} Tamara [midling About the public forums, the idea and the need Should we talk about the war? us, in whose name the wars had been lead protagonists are former soldiers, ‘Whatever happened it's all water and provoked. We carry our responsibility participants of the wars taking place in the under the bridge! It's everyone's fault. The because we have either supported creat- region of former Yugoslavia during the war is evil. -

Serbia Guidebook 2013

SERBIA PREFACE A visit to Serbia places one in the center of the Balkans, the 20th century's tinderbox of Europe, where two wars were fought as prelude to World War I and where the last decade of the century witnessed Europe's bloodiest conflict since World War II. Serbia chose democracy in the waning days before the 21st century formally dawned and is steadily transforming an open, democratic, free-market society. Serbia offers a countryside that is beautiful and diverse. The country's infrastructure, though over-burdened, is European. The general reaction of the local population is genuinely one of welcome. The local population is warm and focused on the future; assuming their rightful place in Europe. AREA, GEOGRAPHY, AND CLIMATE Serbia is located in the central part of the Balkan Peninsula and occupies 77,474square kilometers, an area slightly smaller than South Carolina. It borders Montenegro, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina to the west, Hungary to the north, Romania and Bulgaria to the east, and Albania, Macedonia, and Kosovo to the south. Serbia's many waterway, road, rail, and telecommunications networks link Europe with Asia at a strategic intersection in southeastern Europe. Endowed with natural beauty, Serbia is rich in varied topography and climate. Three navigable rivers pass through Serbia: the Danube, Sava, and Tisa. The longest is the Danube, which flows for 588 of its 2,857-kilometer course through Serbia and meanders around the capital, Belgrade, on its way to Romania and the Black Sea. The fertile flatlands of the Panonian Plain distinguish Serbia's northern countryside, while the east flaunts dramatic limestone ranges and basins. -

Jewish Citizens of Socialist Yugoslavia: Politics of Jewish Identity in a Socialist State, 1944-1974

JEWISH CITIZENS OF SOCIALIST YUGOSLAVIA: POLITICS OF JEWISH IDENTITY IN A SOCIALIST STATE, 1944-1974 by Emil Kerenji A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Todd M. Endelman, Co-Chair Professor John V. Fine, Jr., Co-Chair Professor Zvi Y. Gitelman Professor Geoffrey H. Eley Associate Professor Brian A. Porter-Szűcs © Emil Kerenji 2008 Acknowledgments I would like to thank all those who supported me in a number of different and creative ways in the long and uncertain process of researching and writing a doctoral dissertation. First of all, I would like to thank John Fine and Todd Endelman, because of whom I came to Michigan in the first place. I thank them for their guidance and friendship. Geoff Eley, Zvi Gitelman, and Brian Porter have challenged me, each in their own ways, to push my thinking in different directions. My intellectual and academic development is equally indebted to my fellow Ph.D. students and friends I made during my life in Ann Arbor. Edin Hajdarpašić, Bhavani Raman, Olivera Jokić, Chandra Bhimull, Tijana Krstić, Natalie Rothman, Lenny Ureña, Marie Cruz, Juan Hernandez, Nita Luci, Ema Grama, Lisa Nichols, Ania Cichopek, Mary O’Reilly, Yasmeen Hanoosh, Frank Cody, Ed Murphy, Anna Mirkova are among them, not in any particular order. Doing research in the Balkans is sometimes a challenge, and many people helped me navigate the process creatively. At the Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade, I would like to thank Milica Mihailović, Vojislava Radovanović, and Branka Džidić. -

Annual Report 2014

REPUBLIC OF SERBIA PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS 22 - 3 / 15 B e l g r a d e Ref. No. 7919 Date: 14 March 2015 REGULAR ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS FOR 2014 Belgrade, 14 March 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS: REGULAR ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS FOR 2014 ............................... 1 FOREWORD, OVERALL ASSESMENT OF RESPECT FORTHE RIGHTS OF CITIZENS AND KEY INFORMATION ON THE ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT BY THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS in 2014 ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 KEY STATISTICS ABOUT THE WORK OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS ......................... 21 PART I: LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND SCOPE OF WORK OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS .. 25 1.1. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................ 25 1.2. COMPETENCE, SCOPE AND MANNER OF WORK ............................................................ 32 PART II: OVERVIEW BY AREAS / SECTORS ..................................................................................... 36 2.1. CHILD RIGHTS ............................................................................................................................ 36 2.2. RIGHTS OF NATIONAL MINORITIES .................................................................................... 54 2.3. GENDER EQUALITY AND RIGHTS OF LGBTI PERSONS .................................................. 70 2.4. RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES -

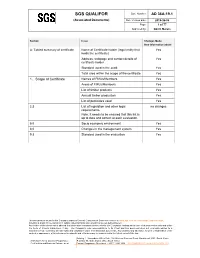

SGS QUALIFOR Doc

SGS QUALIFOR Doc. Number: AD 36A-19.1 (Associated Documents) Doc. Version date: 2019-06-06 Page: 1 of 77 Approved by: Gerrit Marais Section Issue Changes Made New Information added A: Tabled summary of certificate Name of Certificate holder (legal entity that Yes holds the certificate) Address, webpage and contact details of Yes certificate holder Standard used in the audit Yes Total area within the scope of the certificate Yes 1. Scope of Certificate Names of FMUs/Members Yes Areas of FMUs/Members Yes List of timber products Yes Annual timber production Yes List of pesticides used Yes 2.3 List of legislation and other legal no changes requirements. Note: It needs to be ensured that this list is up to date and correct at each evaluation. 5.0 Socio economic environment Yes 8.0 Changes in the management system Yes 9.3 Standard used in the evaluation Yes This document is issued by the Company under its General Conditions of Service accessible at www.sgs.com/en/Terms-and-Conditions.aspx. Attention is drawn to the limitation of liability, indemnification and jurisdiction issues defined therein. Any holder of this document is advised that information contained hereon reflects the Company’s findings at the time of its intervention only and within the limits of Client’s instructions, if any. The Company’s sole responsibility is to its Client and this document does not exonerate parties to a transaction from exercising all their rights and obligations under the transaction documents. Any unauthorized alteration, forgery or falsification of the content or appearance of this document is unlawful and offenders may be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. -

St. Ignatius of Loyola and Sāntideva As Companions on the Way of Life Tomislav Spiranec

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations Student Scholarship 4-2018 Virtues/Pāramitās: St. Ignatius Of Loyola and Sāntideva as Companions on the Way of Life Tomislav Spiranec Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Spiranec, Tomislav, "Virtues/Pāramitās: St. Ignatius Of Loyola and Sāntideva as Companions on the Way of Life" (2018). Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations. 17. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations/17 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIRTUES/PARA.MIT .AS: ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA AND SANTIDEVA AS COMPANIONS ON THE WAY OF LIFE A dissertation by Tomislav Spiranec, S.J. presented to The Faculty of the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Sacred Theology Berkeley, California April, 2018 Committee ------===~~~~~~~j_ 't /l!;//F Dr. Eduardo Fernandez, S.J., S.T. 4=:~ .7 Alexander, Ph.D., Reader lf/ !~/lg Ph.D., Reader y/lJ/li ------------',----\->,----"'~----'- Abstract VIRTUES/PARAMIT AS: ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA AND SANTIDEVA AS COMPANIONS ON THE WAY OF LIFE Tomislav Spiranec, S.J. This dissertation conducts a comparative study of the cultivation of the virtues in Catholic spiritual tradition and the perfections (paramitas) in the Mahayana Buddhist traditions in view of the spiritual needs of contemporary Croatian young adults. -

Serbia 2Nd Periodical Report

Strasbourg, 23 September 2010 MIN-LANG/PR (2010) 7 EUROPEAN CHARTER FOR REGIONAL OR MINORITY LANGUAGES Second periodical report presented to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe in accordance with Article 15 of the Charter SERBIA The Republic of Serbia The European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages The Second Periodical Report Submitted to the Secretary General of the Council of Europe Pursuant to Article 15 of the Charter Belgrade, September 2010 2 C O N T E N T S 1. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………6 2. Part I …………………………………………………………………………………12 2.1. Legislative and institutional changes after the first cycle of monitoring of the implementation of the Charter …………………………………………………….12 2.1.1. Legislative changes ……………………………………………………….12 2.1.2. The National Strategy for the Improvement of the Status of Roma ……..17 2.1.3. Judicial Reform …………………………………………………………...17 2.1.4. Establishment of the Ministry of Human and Minority Rights …………..23 2.2. Novelties expected during the next monitoring cycle of the implementation of the Charter …………………………………………………………………………….24 2.2.1. The Census ………………………………………………………………..24 2.2.2. Election of the national councils of the national minorities ……………...26 2.3. Implementation of the recommendations of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe (RecChL(2009)2) 28) …………………………………………29 2.4. Activities for the implementation of the box-recommendation of the Committee of Experts with regard to the implementation of the Charter ………………………...33 3. PART II Implementation of Article 7 of the Charter ……………………………..38 3.1. Information on the policy, legislation and practice in the implementation of Part II - Article 7 of the Charter ……………………………………………………………..38 3.1.1. -

Media News Bulletin No 4

Issue No. 4 May 12 – May 24, 2011 Content New negative assessments of the media situation – Draft Media Strategy to be completed by June 1 – Protests against lenient sentences for attackers on journalists continue – Lawsuit filed against the Commissioner for Information of Public Importance – Prosecutor's Office investigates warmongering propaganda – Further escalation of attacks and threats against journalists and the media – New desecration of the memorial plate dedicated to Curuvija . ASMEDI becomes member of the ENPA – Assembly of the European Federation of Journalists to be held in Belgrade – Web site Juzne Vesti has 6,000 visits a day – Awards to journalists and the media - 500th issue of REPUBLIKA – Apology of the Managing Board of the Public Service Broadcaster and reactions – BETA protests to NUNS . SBB increases prices again – Revenue of RTV grows – Analysis of business results of the media – Municipality wants to become owner of Pancevac again – Securities Commission examines privatization of Novosti – Media boycott of the Municipal Assembly in Bajina Basta – Agreement on airing of parliamentary sessions soon to be reached – Radio Bor begins broadcasting programe again . Protests by NUNS, NDNV, UNS and SEEMO against attacks on journalists and light sentences for attackers – RATEL publishes roaming tariffs – RRA punishes overstepping of advertising limits – President of RRA violates Church canons, claims "ALO!" – Media trade unions of Politika hold a protest – Media strikes in Smederevo and Kragujevac . PI channel Pirot available on GSS IPTV network – Supplement of Danas, "Sandzak", published in Istanbul – Redesigned web site 24Sata – New morning programme of Radio B92 – ABC Serbia in new business premises Assessments of the current media situation in Serbia The media situation in Serbia has worsened since 2006, shows the Media Sustainability Index (MSI) for the year of 2010 issued by IREX, an American NGO for support to the media. -

Selected Works from the Art Collection

SELECTED WORKS FROM THE ART COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS RESPONSIBLY IN CULTURE............................................5 ON THE ART COLLECTION OF VOJVOĐANSKA BANKA....7 CATALOG OF WORKS JOVANA POPOVIĆ BENIŠEK............................................ 12 ZDRAVKO MANDIĆ........................................................... 58 JOVAN BIKICKI.................................................................. 14 ŽIVOJIN ŽIKA MIŠKOV..................................................... 60 PAVLE BLESIĆ................................................................... 16 PETAR MOJAK.................................................................. 62 ISIDOR BATA VRSAJKOV.................................................. 18 MILIVOJ NIKOLAJEVIĆ.................................................... 64 BRANISLAV BANE VULEKOVIĆ........................................20 ANKICA OPREŠNIK.......................................................... 66 NIKOLA GRAOVAC............................................................. 22 BOŠKO PETROVIĆ............................................................ 72 VERA ZARIĆ.......................................................................26 ZORAN PETROVIĆ............................................................ 74 BOGOMIL KARLAVARIS....................................................28 MIODRAG MIĆA POPOVIĆ................................................76 MILAN KERAC................................................................... 30 MILAN SOLAROV............................................................. -

Scholars Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Why Doesn't

Scholars Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: Sch J Arts Humanit Soc Sci ISSN 2347-9493 (Print) | ISSN 2347-5374 (Online) Journal homepage: https://saspublishers.com/sjahss/ Why Doesn't Capitalism Work in Croatia? Marko Šarić* Ph.D Candidat, Faculty of Logistics, Maribor State University, Slovenia, Europa DOI: 10.36347/sjahss.2020.v08i04.006 | Received: 15.02.2020 | Accepted: 03.03.2020 | Published: 14.04.2020 *Corresponding author: Marko Šarić Abstract Original Research Article The paper will analyze all geoeconomic, geopolitical and geostrategic forces that influence the unfavorable development of the republic of croatia. The republic of croatia is lagging behind the development of all other eu member states. State interventions in many economic sectors (transport, agriculture, energy, shipbuilding) do not produce any positive results and destroy croatia's competitiveness. Numerous crypto-communist public officials and the croatian catholic church are campaigning very aggressively against market capitalism. Keywords: Croatia, Marxism, capitalism, Catholicism, trade unions. Copyright @ 2020: This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium for non-commercial use (NonCommercial, or CC-BY-NC) provided the original author and source are credited. NTRODUCTION describing facts and objects in nature and society and I their empirical validation of relationships. Croatia today, is -

Michael Z. Vinokouroff: a Profile and Inventory of His Papers And

MICHAEL Z. VINOKOUROFF: A PROFILE AND INVENTORY OF HIS PAPERS (Ms 81) AND PHOTOGRAPHS (PCA 243) in the Alaska Historical Library Louise Martin, Ph.D. Project coordinator and editor Alaska Department of Education Division ofState Libraries P.O. Box G Juneau Alaska 99811 1986 Martin, Louise. Michael Z. Vinokouroff: a profile and inventory of his papers (MS 81) and photographs (PCA 243) in the Alaska Historical Library / Louise Martin, Ph.D., project coordinator and editor. -- Juneau, Alaska (P.O. Box G. Juneau 99811): Alaska Department of Education, Division of State Libraries, 1986. 137, 26 p. : ill.; 28 cm. Includes index and references to photographs, church and Siberian material available on microfiche from the publisher. Partial contents: M.Z. Vinokouroff: profile of a Russian emigre scholar and bibliophile/ Richard A. Pierce -- It must be done / M.Z.., Vinokouroff; trans- lation by Richard A. Pierce. 1. Orthodox Eastern Church, Russian. 2. Siberia (R.S.F.S.R.) 3. Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America--Diocese of Alaska--Archives-- Catalogs. 4. Vinokour6ff, Michael Z., 1894-1983-- Library--Catalogs. 5. Soviet Union--Emigrationand immigration. 6. Authors, Russian--20th Century. 7. Alaska Historical Library-- Catalogs. I. Alaska. Division of State Libraries. II. Pierce, Richard A. M.Z. Vinokouroff: profile of a Russian emigre scholar and bibliophile. III. Vinokouroff, Michael Z., 1894- 1983. It must be done. IV. Title. DK246 .M37 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................. 1 “M.Z. Vinokouroff: Profile of a Russian Émigré Scholar and Bibliophile,” by Richard A. Pierce................... 5 Appendix: “IT MUST BE DONE!” by M.Z. Vinokouroff; translation by Richard A. -

SERBIA: Violent Attacks Continuing, but Mainly Declining

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 3 December 2008 SERBIA: Violent attacks continuing, but mainly declining By Drasko Djenovic, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> The latest Forum 18 News Service survey of violent attacks against Serbia's religious communities - covering September 2007 to October 2008 - indicates that fewer attacks are taking place compared to previous years. As previously, most physical attacks have been on Seventh-day Adventist and Jehovah's Witnesses properties, and attacks on Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (commonly known as Mormons) properties have risen. As in earlier years, a number of Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries have also suffered attacks. Dragan Novakovic, the Deputy Religion Minister, told Forum 18 that the police and judicial authorities do not provide his Ministry with adequate information. Novakovic also regretted that attackers are usually charged with violating public order, instead of - where appropriate - the more serious charge of inciting or exacerbating national, racial, or religious hatred - which carries higher penalties than public order charges. Novakovic told Forum 18 that the Ministry is determined to reduce attacks. "We will need years to get it down to an acceptable level, but we are determined to do it." The latest Forum 18 News Service survey of violent attacks on Serbia's religious communities and their members - covering September 2007 to October 2008 - seems to indicate that fewer attacks are now taking place overall, especially compared to the years up to about 2006.