State Violence in Serbia and Montenegro an Alternative Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Analysis of Parafiscal Burdens at Local Level

Report on parafiscal charges in Montenegro THE ANALYSIS OF PARAFISCAL BURDENS AT LOCAL LEVEL Municipalities Danilovgrad, Bijelo Polje and Budva - Summary - Note This document is a summary, i.e. a brief overview of a part of the content of the original publication published by Montenegrin Employers Federation (MEF) in Mon- tenegrin language as a “Report on parafiscal charges in Montenegro: The Analysis of Parafiscal Burdens at -Lo cal level - Municipalities Danilovgrad, Bijelo Polje and Budva”. Original version of the publication is available at MEF website www.poslodavci.org Report on parafiscal charges in Montenegro THE ANALYSIS OF PARAFISCAL BURDENS AT LOCAL LEVEL - Municipalities Danilovgrad, Bijelo Polje and Budva - SUMMARY Podgorica, November 2018 Title: Report on parafiscal charges in Montenegro:THE ANALYSIS OF PARAFISCAL BURDENS AT LOCAL LEVEL - Municipalities Danilovgrad, Bijelo Polje and Budva Authors: dr Vasilije Kostić Montenegrin Employers’ Federation Publisher: Montenegrin Employers Federation (MEF) Cetinjski put 36 81 000 Podgorica, Crna Gora T: +382 20 209 250 F: +382 20 209 251 E: [email protected] W: www.poslodavci.org For publisher: Suzana Radulović Place and date: Podgorica, December 2018 This publication has been published with the support of the (Bureau for Employers` Activities of the) International Labour Organization. The responsibility for the opinions expressed in this report rests solely with the authors. The International Labour -Or ganisation (ILO) takes no responsibility for the correctness, accuracy or reliability of any of the materials, information or opinions expressed in this report. Executive Summary It is common knowledge that productivity determines the limits of development of the standard of living of any country, and modern globalized economy emphasizes the importance of productivity to the utmost limits. -

Socio Economic Analysis of Northern Montenegrin Region

SOCIO ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE NORTHERN REGION OF MONTENEGRO Podgorica, June 2008. FOUNDATION F OR THE DEVELOPMENT O F NORTHERN MONTENEGRO (FORS) SOCIO -ECONOMIC ANLY S I S O F NORTHERN MONTENEGRO EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR : Veselin Šturanović STUDY REVIEWER S : Emil Kočan, Nebojsa Babovic, FORS Montenegro; Zoran Radic, CHF Montenegro IN S TITUTE F OR STRATEGIC STUDIE S AND PROGNO S E S ISSP’S AUTHOR S TEAM : mr Jadranka Kaluđerović mr Ana Krsmanović mr Gordana Radojević mr Ivana Vojinović Milica Daković Ivan Jovetic Milika Mirković Vojin Golubović Mirza Mulešković Marija Orlandić All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means wit- hout the prior written permission of FORS Montenegro. Published with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the CHF International, Community Revitalization through Democratic Action – Economy (CRDA-E) program. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for Interna- tional Development. For more information please contact FORS Montenegro by email at [email protected] or: FORS Montenegro, Berane FORS Montenegro, Podgorica Dušana Vujoševića Vaka Đurovića 84 84300, Berane, Montenegro 81000, Podgorica, Montenegro +382 51 235 977 +382 20 310 030 SOCIO ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE NORTHERN REGION OF MONTENEGRO CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS: ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Important Business Zones - Potentials

DANILOVGRAD IN NUMBERS • Surface area: 501 km² • Population: 18.472 (2011 census) – increased for 12% since 2003 census • Elevation from 30 to 2100 MASL • Valleys - up to 200 MASL – 140,5 km² • Hills - up to 600 MASL– 81 km² • Mountains above 650 MASL – 275 km² • Highest peaks – Garač (Peak Bobija) 1436 MASL, Ponikvica (Peak Kula) 1927 MASL and Maganik (Petrov Peak) 2127 MASL COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGES • Strategic geographic location • Transport connections • Defined industrial (business) zones • Development resources • Efficient local administration • Incentive measures and subventiones STRATEGIC GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION TRANSPORT CONNECTIONS • 18 km from capital city Podgorica • 25 km from International Airport (Golubovci) • 70 km from International Seaport (Bar) • 20 km from highway Bar – Boljare which is in construction • 10 km from future Adriatic – Ionian highway (Italy – Slovenia – Croatia – Bosnia and Hercegovina – Albania – Greece) • Rail transport DEFINED INDUSTRIAL (BUSINESS) ZONES • 2007 year - Spatial Plan was adopted with defined industrial (business) zones • 2014 year – Spatial – urban Plan was adopted with defined additional industrial (business) zones • The biggest zones are along the major roads: European route E762 Sarajevo – Podgorica – Tirana (12 km) – 100 m from both sides Regional road Bogetići – Danilovgrad – Spuž – Podgorica (11 km) – 100 m from both sides IMPORTANT BUSINESS ZONES - POTENTIALS DANILOVGRAD – ŽDREBAONIK MONASTERY • Built infrastructure • Religious tourism and accommodation capacities (Ždrebaonik Monastery) -

4 VIEWS. from the Past: How I Found Myself in War?

FROM THE PAST: HOW I FOUND MYSELF IN WAR TOWARDS THE FUTURE: HOW TO REACH SUSTAINABLE PEACE 44POGLEDPOGLEDAA VLASOTINCE SPEAKERS ON THE PUBLIC FORUMS 24.10.2003. WERE PEOPLE WHO PARTICIPATED IN WARS IN THE REGION OF FORMER YUGOSLAVIA ADNAN HASANBEGOVI] IZ SARAJEVA NOVI SAD DRAGO FRAN^I[KOVI] IZ ZAGREBA 28.10.2003. GORDAN BODOG IZ ZAGREBA KEMAL BUKVI] IZ ZAGREBA KRALJEVO NERMIN KARA^I] IZ SARAJEVA 11.11.2003. NOVICA KOSTI] IZ VLASOTINCA INITIATIVE AND ORGANISATION CENTAR ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU CENTRE FOR NONVIOLENT ACTION Office in Belgrade Office in Sarajevo Studentski trg 8, 11000 Beograd, SCG Radni~ka 104, 71000 Sarajevo, BiH Tel: +381 11 637-603, 637-661 Tel: +387 33 212-919, 267-880 Fax: +381 11 637-603 Fax: +387 33 212-919 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.nenasilje.org IN COOPERATION WITH UDRU@ENJE BORACA RATA 90. VLASOTINCE DRU[TVO ZA NENASILNU AKCIJU from Novi Sad OMLADINSKA ORGANIZACIJA KVART from Kraljevo Publication edited and articles written by activists of Centre for Nonviolent Action Adnan Hasanbegovi} Helena Rill Ivana Franovi} Milan Coli} Humljan Ned`ad Horozovi} Nenad Vukosavljevi} Sanja Deankovi} Tamara [midling About the public forums, the idea and the need Should we talk about the war? us, in whose name the wars had been lead protagonists are former soldiers, ‘Whatever happened it's all water and provoked. We carry our responsibility participants of the wars taking place in the under the bridge! It's everyone's fault. The because we have either supported creat- region of former Yugoslavia during the war is evil. -

USAID Economic Growth Project

USAID Economic Growth Project BACKGROUND The USAID Economic Growth Project is a 33-month initiative designed to increase economic opportunity in northern Montenegro. Through activities in 13 northern municipalities, the Economic Growth Project is promoting private-sector development to strengthen the competitiveness of the tourism sector, increase the competitiveness of agriculture and agribusiness, and improve the business-enabling environment at the municipal level. ACTIVITIES The project provides assistance to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, local tourist organizations, and business support service providers, as well as municipal governments to stimulate private sector growth. The project is: Strengthening the competitiveness of the tourism sector It is promoting the north as a tourist destination by supporting innovative service providers, building the region’s capacity to support tourism, assisting coordination with coastal tourism businesses, and expanding access to tourist information. Improving the viability of agriculture and agribusiness It is restoring agriculture as a viable economic activity by supporting agricultural producers and processors from the north to capitalize on market trends and generate more income. Bettering the business-enabling environment It is identifying barriers to doing business and assisting municipalities to execute plans to lower these obstacles by providing services and targeted investment. RESULTS 248 businesses have received assistance from Economic Growth Project (EGP)-supported activities. Sales of items produced by EGP-supported small businesses have increased by 15.8 percent since the project began. Linkages have been established between 111 Northern firms, as well as between Northern firms and Central and Southern firms. 26 EGP-assisted companies invested in improved technologies, 29 improved management practices, and 31 farmers, processors, and other firms adopted new technologies or management practices. -

Territorial Area of Montenegro Municipalities

14/10/2013 Legal and political context of ANALYSIS Montenegro of the legal status and • Independent, autonomous, internationally functioning of public recognized country • As per its state organization, Montenegro is a authority entities in simple country principally financed by the EU the by financed principally Montenegro • As per its type of government , Montenegro is a Republic A joint initiative of the OECD and the European Union, European the and OECD the of initiative A joint • As per its political regime, it is a democratic Prof.dr Đorđije Blažić country, as well as an ecological, social justice and International Benchmarking Seminar rule of law country Danilovgrad, Montenegro 9-11 October 2013 • As per its power organization, i.e. the power division system (legislative executive and judicial 2 © OECD power) Number and structure of Territorial area of Montenegro municipalities Crna Gora Andrijevica Bar Berane Bijelo Polje Budva Danilovgrad Žabljak Kolašin Kotor Mojkovac Montenegro Broj mjesnih Broj opština Broj naselja Gradska naselja 13 812 283 598 717 924 122 501 445 897 335 367 zajednica Number of Number of Urban Number of local municipalities settlements settlements communities Herceg Nikšić Plav Plužine Pljevlja Podgorica Rožaje Tivat Ulcinj Cetinje Šavnik Novi 21 1,256 40 368 2 065 486 854 1 346 1 441 432 46 255 235 910 553 3 4 Land and coastal boundaries (Coast Srednja mjesečna temperatura vazduha line) AVERAGE MONTHLY AIR TEMPERATURE (º C) Srednja Kopnena granica prema / Land boundary with godišnj a Hrvatskoj B i H Srbiji -

Serbia Guidebook 2013

SERBIA PREFACE A visit to Serbia places one in the center of the Balkans, the 20th century's tinderbox of Europe, where two wars were fought as prelude to World War I and where the last decade of the century witnessed Europe's bloodiest conflict since World War II. Serbia chose democracy in the waning days before the 21st century formally dawned and is steadily transforming an open, democratic, free-market society. Serbia offers a countryside that is beautiful and diverse. The country's infrastructure, though over-burdened, is European. The general reaction of the local population is genuinely one of welcome. The local population is warm and focused on the future; assuming their rightful place in Europe. AREA, GEOGRAPHY, AND CLIMATE Serbia is located in the central part of the Balkan Peninsula and occupies 77,474square kilometers, an area slightly smaller than South Carolina. It borders Montenegro, Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina to the west, Hungary to the north, Romania and Bulgaria to the east, and Albania, Macedonia, and Kosovo to the south. Serbia's many waterway, road, rail, and telecommunications networks link Europe with Asia at a strategic intersection in southeastern Europe. Endowed with natural beauty, Serbia is rich in varied topography and climate. Three navigable rivers pass through Serbia: the Danube, Sava, and Tisa. The longest is the Danube, which flows for 588 of its 2,857-kilometer course through Serbia and meanders around the capital, Belgrade, on its way to Romania and the Black Sea. The fertile flatlands of the Panonian Plain distinguish Serbia's northern countryside, while the east flaunts dramatic limestone ranges and basins. -

Jewish Citizens of Socialist Yugoslavia: Politics of Jewish Identity in a Socialist State, 1944-1974

JEWISH CITIZENS OF SOCIALIST YUGOSLAVIA: POLITICS OF JEWISH IDENTITY IN A SOCIALIST STATE, 1944-1974 by Emil Kerenji A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Todd M. Endelman, Co-Chair Professor John V. Fine, Jr., Co-Chair Professor Zvi Y. Gitelman Professor Geoffrey H. Eley Associate Professor Brian A. Porter-Szűcs © Emil Kerenji 2008 Acknowledgments I would like to thank all those who supported me in a number of different and creative ways in the long and uncertain process of researching and writing a doctoral dissertation. First of all, I would like to thank John Fine and Todd Endelman, because of whom I came to Michigan in the first place. I thank them for their guidance and friendship. Geoff Eley, Zvi Gitelman, and Brian Porter have challenged me, each in their own ways, to push my thinking in different directions. My intellectual and academic development is equally indebted to my fellow Ph.D. students and friends I made during my life in Ann Arbor. Edin Hajdarpašić, Bhavani Raman, Olivera Jokić, Chandra Bhimull, Tijana Krstić, Natalie Rothman, Lenny Ureña, Marie Cruz, Juan Hernandez, Nita Luci, Ema Grama, Lisa Nichols, Ania Cichopek, Mary O’Reilly, Yasmeen Hanoosh, Frank Cody, Ed Murphy, Anna Mirkova are among them, not in any particular order. Doing research in the Balkans is sometimes a challenge, and many people helped me navigate the process creatively. At the Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade, I would like to thank Milica Mihailović, Vojislava Radovanović, and Branka Džidić. -

Annual Report 2014

REPUBLIC OF SERBIA PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS 22 - 3 / 15 B e l g r a d e Ref. No. 7919 Date: 14 March 2015 REGULAR ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS FOR 2014 Belgrade, 14 March 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS: REGULAR ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS FOR 2014 ............................... 1 FOREWORD, OVERALL ASSESMENT OF RESPECT FORTHE RIGHTS OF CITIZENS AND KEY INFORMATION ON THE ACTIVITIES CARRIED OUT BY THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS in 2014 ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 KEY STATISTICS ABOUT THE WORK OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS ......................... 21 PART I: LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND SCOPE OF WORK OF THE PROTECTOR OF CITIZENS .. 25 1.1. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................ 25 1.2. COMPETENCE, SCOPE AND MANNER OF WORK ............................................................ 32 PART II: OVERVIEW BY AREAS / SECTORS ..................................................................................... 36 2.1. CHILD RIGHTS ............................................................................................................................ 36 2.2. RIGHTS OF NATIONAL MINORITIES .................................................................................... 54 2.3. GENDER EQUALITY AND RIGHTS OF LGBTI PERSONS .................................................. 70 2.4. RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES -

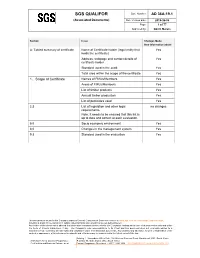

SGS QUALIFOR Doc

SGS QUALIFOR Doc. Number: AD 36A-19.1 (Associated Documents) Doc. Version date: 2019-06-06 Page: 1 of 77 Approved by: Gerrit Marais Section Issue Changes Made New Information added A: Tabled summary of certificate Name of Certificate holder (legal entity that Yes holds the certificate) Address, webpage and contact details of Yes certificate holder Standard used in the audit Yes Total area within the scope of the certificate Yes 1. Scope of Certificate Names of FMUs/Members Yes Areas of FMUs/Members Yes List of timber products Yes Annual timber production Yes List of pesticides used Yes 2.3 List of legislation and other legal no changes requirements. Note: It needs to be ensured that this list is up to date and correct at each evaluation. 5.0 Socio economic environment Yes 8.0 Changes in the management system Yes 9.3 Standard used in the evaluation Yes This document is issued by the Company under its General Conditions of Service accessible at www.sgs.com/en/Terms-and-Conditions.aspx. Attention is drawn to the limitation of liability, indemnification and jurisdiction issues defined therein. Any holder of this document is advised that information contained hereon reflects the Company’s findings at the time of its intervention only and within the limits of Client’s instructions, if any. The Company’s sole responsibility is to its Client and this document does not exonerate parties to a transaction from exercising all their rights and obligations under the transaction documents. Any unauthorized alteration, forgery or falsification of the content or appearance of this document is unlawful and offenders may be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law. -

St. Ignatius of Loyola and Sāntideva As Companions on the Way of Life Tomislav Spiranec

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations Student Scholarship 4-2018 Virtues/Pāramitās: St. Ignatius Of Loyola and Sāntideva as Companions on the Way of Life Tomislav Spiranec Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Spiranec, Tomislav, "Virtues/Pāramitās: St. Ignatius Of Loyola and Sāntideva as Companions on the Way of Life" (2018). Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations. 17. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations/17 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIRTUES/PARA.MIT .AS: ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA AND SANTIDEVA AS COMPANIONS ON THE WAY OF LIFE A dissertation by Tomislav Spiranec, S.J. presented to The Faculty of the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Sacred Theology Berkeley, California April, 2018 Committee ------===~~~~~~~j_ 't /l!;//F Dr. Eduardo Fernandez, S.J., S.T. 4=:~ .7 Alexander, Ph.D., Reader lf/ !~/lg Ph.D., Reader y/lJ/li ------------',----\->,----"'~----'- Abstract VIRTUES/PARAMIT AS: ST. IGNATIUS OF LOYOLA AND SANTIDEVA AS COMPANIONS ON THE WAY OF LIFE Tomislav Spiranec, S.J. This dissertation conducts a comparative study of the cultivation of the virtues in Catholic spiritual tradition and the perfections (paramitas) in the Mahayana Buddhist traditions in view of the spiritual needs of contemporary Croatian young adults. -

Montenegro: Floods DREF Operation N° MDRME003 16 November 2010

DREF operation n° MDRME003 Montenegro: Floods 16 November 2010 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent emergency response. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. CHF 50,256 (USD 51,384 or EUR 37,763) has been allocated from the IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DRE F) to support the National Society in delivering immediate assistance to some 1350 beneficiaries. Unearmarked funds to repay DREF are encouraged. Summary: Heavy rains over the past four days caused floods in central and northern parts of Montenegro, causing severe damage, especially in three municipalities up north. 270 families were evacuated (around 1350 persons), and are in need of basic emergency relief items. The Red Cross of Montenegro has already assisted the evacuated population with some of these items, and plans to continue with the distribution, th according to the development of the Plav, November 10 2010. Photo: Red Cross of Montenegro situation in the field. This operation is expected to be implemented over 3 months, and will therefore be completed by the end of February 2011; a Final Report will be made available three months after the end of the operation (by May 2011). <click here for the DREF budget; here for contact details> The situation Within the last four days massive rainfalls have affected Montenegro causing floods in the central and northern parts of the country.