Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: New Perspectives on Production, Reception, Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snow White and the Little Men -2

SNOW WHITE AND THE LITTLE MEN (Based very loosely upon the tales by the Bros. Grimm. First produced at Brown Ledge Camp, 1975.) Conceived and Written by WILLIAM J. SPRINGER Performance Rights To copy this text is an infringement of the federal copyright law as is to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Call the publisher for further scripts and licensing information. On all programs and advertising the author’s name must appear as well as this notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Company.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY www.histage.com © 1978 by Eldridge Publishing Company Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing https://histage.com/snow-white-and-the-little-men Snow White and the Little Men -2- Story of the Play In this farce, a narrator helps the action and humor even to the point of carrying off the good queen, who doesn’t want to die after Snow White, is born. The evil queen can’t make up a rhyme that’s worth a darn before the magic mirror, and she even forgets her apples are poisonous and eats one at the wedding of the Prince and Snow. Snow White and the Little Men -3- CAST OF CHARACTERS NARRATOR GOOD QUEEN CREW MEMBER NURSE KING ANOTHER WIFE MAN EVIL QUEEN MIRROR SNOW WHITE HUNTSMAN BORE DWARF #1 DWARF #3 DWARF #5 DWARF #7 PRINCE (DWARFS #2, 4 and 6 are dummies supported between the odd-numbered DWARFS.) Snow White and the Little Men -4- SNOW WHITE AND THE LITTLE MEN (AT RISE: There is a stool SL which the NARRATOR will sit on and a chair or short stool SR which serves as the throne for the GOOD QUEEN. -

UPA : Redesigning Animation

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. UPA : redesigning animation Bottini, Cinzia 2016 Bottini, C. (2016). UPA : redesigning animation. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/69065 https://doi.org/10.32657/10356/69065 Downloaded on 05 Oct 2021 20:18:45 SGT UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI SCHOOL OF ART, DESIGN AND MEDIA 2016 UPA: REDESIGNING ANIMATION CINZIA BOTTINI School of Art, Design and Media A thesis submitted to the Nanyang Technological University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.” Paul Klee, “Creative Credo” Acknowledgments When I started my doctoral studies, I could never have imagined what a formative learning experience it would be, both professionally and personally. I owe many people a debt of gratitude for all their help throughout this long journey. I deeply thank my supervisor, Professor Heitor Capuzzo; my cosupervisor, Giannalberto Bendazzi; and Professor Vibeke Sorensen, chair of the School of Art, Design and Media at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for showing sincere compassion and offering unwavering moral support during a personally difficult stage of this Ph.D. I am also grateful for all their suggestions, critiques and observations that guided me in this research project, as well as their dedication and patience. My gratitude goes to Tee Bosustow, who graciously -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values Allyson Scott California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Scott, Allyson, "Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 391. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/391 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social and Behavioral Sciences Department Senior Capstone California State University, Monterey Bay Almost There: A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values Dr. Rebecca Bales, Capstone Advisor Dr. Gerald Shenk, Capstone Instructor Allyson Scott Spring 2012 Acknowledgments This senior capstone has been a year of research, writing, and rewriting. I would first like to thank Dr. Gerald Shenk for agreeing that my topic could be more than an excuse to watch movies for homework. Dr. Rebecca Bales has been a source of guidance and reassurance since I declared myself an SBS major. Both have been instrumental to the completion of this project, and I truly appreciate their humor, support, and advice. -

The University of Chicago Looking at Cartoons

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LOOKING AT CARTOONS: THE ART, LABOR, AND TECHNOLOGY OF AMERICAN CEL ANIMATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA AND MEDIA STUDIES BY HANNAH MAITLAND FRANK CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 FOR MY FAMILY IN MEMORY OF MY FATHER Apparently he had examined them patiently picture by picture and imagined that they would be screened in the same way, failing at that time to grasp the principle of the cinematograph. —Flann O’Brien CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES...............................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................................................................................................viii INTRODUCTION LOOKING AT LABOR......................................................................................1 CHAPTER 1 ANIMATION AND MONTAGE; or, Photographic Records of Documents...................................................22 CHAPTER 2 A VIEW OF THE WORLD Toward a Photographic Theory of Cel Animation ...................................72 CHAPTER 3 PARS PRO TOTO Character Animation and the Work of the Anonymous Artist................121 CHAPTER 4 THE MULTIPLICATION OF TRACES Xerographic Reproduction and One Hundred and One Dalmatians.......174 -

Tv Pg 6 3-2.Indd

6 The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, March 2, 2009 All Mountain Time, for Kansas Central TIme Stations subtract an hour TV Channel Guide Tuesday Evening March 2, 2010 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 28 ESPN 57 Cartoon Net 21 TV Land 41 Hallmark ABC Lost Lost 20/20 Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live S&T Eagle CBS NCIS NCIS: Los Angeles The Good Wife Local Late Show Letterman Late 29 ESPN 2 58 ABC Fam 22 ESPN 45 NFL NBC The Biggest Loser Parenthood Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late 2 PBS KOOD 2 PBS KOOD 23 ESPN 2 47 Food FOX American Idol Local 30 ESPN Clas 59 TV Land Cable Channels 3 KWGN WB 31 Golf 60 Hallmark 3 NBC-KUSA 24 ESPN Nws 49 E! A&E Criminal Minds CSI: Miami CSI: Miami Criminal Minds Local 5 KSCW WB 4 ABC-KLBY AMC To-Mockingbird To-Mockingbird Local 32 Speed 61 TCM 25 TBS 51 Travel ANIM 6 Weather Wild Recon Madman of the Sea Wild Recon Untamed and Uncut Madman Local 6 ABC-KLBY 33 Versus 62 AMC 26 Animal 54 MTV BET National Security Vick Tiny-Toya The Mo'Nique Show Wendy Williams Show Security Local 7 CBS-KBSL BRAVO Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Mill. Matchmaker Matchmaker 7 KSAS FOX 34 Sportsman 63 Lifetime 27 VH1 55 Discovery CMT Local Local Smarter Smarter Extreme-Home O Brother, Where Art 8 NBC-KSNK 8 NBC-KSNK 28 TNT 56 Fox Nws CNN 35 NFL 64 Oxygen Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live Anderson Local 9 Eagle COMEDY S. -

Announcer Session: Speaker 1: Ladies and Gentlemen. Speaker 2: Moms and Dads, Speaker 3: Children of All Ages

ACT I Announcer Session: Speaker 1: Ladies and Gentlemen. Speaker 2: Moms and Dads, Speaker 3: Children of all Ages. Speaker 1: Welcome to the wonderful world of Walt Disney! Speaker 2: A magical kingdom where elephants fly, Chimney sweeps dance Speaker 3: And every wish you make comes true. Speaker 1,2, &3: Welcome one and all to the happiest place on earth! Zip-a-dee-doo-dah Zip-a-dee-doo-dah, Zip-a-dee-ay, my oh my, what a wonderful day, Plenty of sunshine headin’ my way, Zip-a-dee-doo-dah, Zip-a-dee-ay. Mister Bluebird on my shoulder, it’s the truth! It’s act’chill’! Everything is satisfactich’ll! Zip-a-dee-doo-dah, Zip-a-dee-ay wonderful feelin’ wonderful day. Wonderful feelin’ it’s a Disney Day. Wonderful Day. How d’ya do and shake hands How d’ya do and shake hands, shake hands, shake hands, Say how d’ya do and shake hands; state your name and business How d’ya do and shake hands, shake hands, shake hands, Say how d’ya do and shake hands; state your name and business Twiddle Dee: You go thru life and never know the day when fate may bring, a situation that will prove to be embarrassing Twiddle Dum: Your face gets red; you hide your head, and wish that you could die. But that’s old fashioned, here’s a new thing you should really try: How d’ya do and shake hands, shake hands, shake hands, Say how d’ya do and shake hands, state your name and business Say how d’ya do and shake hands, shake hands, shake hands, Say how d’ya do and shake hands, state your name and business Bibbidi Bobbidi Boo Sa-la-ga-doo-la, men-chic-ka-boo-la, bib-bi-di-bob-bi-di-boo Put ‘em together and what have you got? bib-bi-di-bob-bi-di-boo Fairy Godmother: Sa-la-ga-doo-la means men-chic-ka-boo-la-roo, but the thing –a-ma-bob that does the job is bib-bi-di-bob-bi-di-boo Sa-la-ga-doo-la, men-chic-ka-boo-la, bib-bi-di-bob-bi-di-boo Put ‘em together and what have you got? bib-bi-di-bob-bi-di, bib-bi-di-bob-bi-di, bib-bi-di-bob-bi-di, bib-bi-di-bob-bi-di, bib-bi-di-bob-bi-di-boo. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Siemens Technology at the New Seven Dwarfs Mine Train

Siemens Technology at the new Seven Dwarfs Mine Train Lake Buena Vista, FL – Since 1937, Snow White and Seven Dwarfs have been entertaining audiences of all ages. As of May 28, 2014, the story found a new home within the largest expansion at the Magic Kingdom® Park. The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train, along with a host of new attractions, shows and restaurants now call New Fantasyland home. The Seven Dwarfs Mine Train, an exciting family coaster, features a forty-foot drop and a series of curves that send guests seated in mine cars swinging and swaying through the hills and caves of the enchanted forest. As part of the systems used to manage the operation of this new attraction, Walt Disney Imagineering chose Siemens to help automate many of the attraction‟s applications. Thanks to Siemens innovations, Sleepy, Doc, Grumpy, Bashful, Sneezy, Happy and Dopey entertain the guests while Siemens technologies are hard at work throughout the infrastructure of the attraction. This includes a host of Siemens‟ systems to ensure that the attraction runs safely and smoothly so that the mine cars are always a required distance from each other. Siemens equipment also delivers real-time information to the Cast Members operating the attraction for enhanced safety, efficiency and communication. The same Safety Controllers, SINAMICS safety variable frequency drives and Scalance Ethernet switches are also found throughout other areas of the new Fantasyland such as the new Dumbo the Flying Elephant®, and Under the Sea – Journey of the Little Mermaid attractions. And Siemens Fire and Safety technologies are found throughout Cinderella Castle. -

Walt Disney and Animation

Name: _________________________ Walt Disney and Animation Directions: Read the passage and answer the questions. Fascinating facts about Walt Disney, Inventor of the Multiplane Camera in 1936. From http://www.ideafinder.com/history/inventors/disney.htm AT A GLANCE: Walt Disney, inventor of the multiplane camera in 1936, is a legend and a folk hero of the 20th century. His worldwide popularity is based upon the ideas his name represents: imagination, optimism, and self-made success in the American tradition. Through his work he brought joy, happiness, and a universal means of communication. Inventor: Walter Elias Disney Criteria: First to invent. First to patent. Entrepreneur.. Birth: December 5, 1901 in Chicago, Illinois. Death: December 16, 1966 Nationality: American Invention: Multiplane Camera in 1936 Function: noun / still frame motion picture camera Definition: Disney’s invention of the multiplane camera brought better looking, richer animation and in 1937, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was the first full-length animated film to use the camera. Patent: 2,201,689 (US) issued May 21, 1940 Milestones: 1923 An aspiring cartoonist leaves for Hollywood 1924 Partnered with older brother Roy, and the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio was officially born. 1928 First Mickey Mouse sound cartoon "Steamboat Willie" released on November 18, in New York. 1930 Mickey made his debut merchandising appearance on pencil tablets, books and comic strips 1936 Walt invents Multiplane Camera to improve the filming quality of his first picture film. 1937 First full-length animated film "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" was released. 1954 "Disneyland" anthology series premiered on network television. -

Rockin Snow White Script

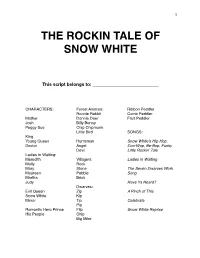

!1 THE ROCKIN TALE OF SNOW WHITE This script belongs to: __________________________ CHARACTERS: Forest Animals: Ribbon Peddler Roonie Rabbit Comb Peddler Mother Donnie Deer Fruit Peddler Josh Billy Bunny Peggy Sue Chip Chipmunk Little Bird SONGS: King Young Queen Huntsman Snow White’s Hip-Hop, Doctor Angel Doo-Wop, Be-Bop, Funky Devil Little Rockin’ Tale Ladies in Waiting: Meredith Villagers: Ladies in Waiting Molly Rock Mary Stone The Seven Dwarves Work Maureen Pebble Song Martha Brick Judy Have Ya Heard? Dwarves: Evil Queen Zip A Pinch of This Snow White Kip Mirror Tip Celebrate Pip Romantic Hero Prince Flip Snow White Reprise His People Chip Big Mike !2 SONG: SNOW WHITE HIP-HOP, DOO WOP, BE-BOP, FUNKY LITTLE ROCKIN’ TALE ALL: Once upon a time in a legendary kingdom, Lived a royal princess, fairest in the land. She would meet a prince. They’d fall in love and then some. Such a noble story told for your delight. ’Tis a little rockin’ tale of pure Snow White! They start rockin’ We got a tale, a magical, marvelous, song-filled serenade. We got a tale, a fun-packed escapade. Yes, we’re gonna wail, singin’ and a-shoutin’ and a-dancin’ till my feet both fail! Yes, it’s Snow White’s hip-hop, doo-wop, be-bop, funky little rockin’ tale! GIRLS: We got a prince, a muscle-bound, handsome, buff and studly macho guy! GUYS: We got a girl, a sugar and spice and-a everything nice, little cutie pie. ALL: We got a queen, an evil-eyed, funkified, lean and mean, total wicked machine.