Dissemination and Refutation of Rumors During the COVID-19 Outbreak in China: Infodemiology Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nosocomial Co-Transmission of Avian Influenza A(H7N9)

SYNOPSIS Nosocomial Co-Transmission of Avian Influenza A(H7N9) and A(H1N1)pdm09 Viruses between 2 Patients with Hematologic Disorders Huazhong Chen,1 Shelan Liu,1 Jun Liu,1 Chengliang Chai, Haiyan Mao, Zhao Yu, Yuming Tang, Geqin Zhu, Haixiao X. Chen, Chengchu Zhu, Hui Shao, Shuguang Tan, Qianli Wang, Yuhai Bi, Zhen Zou, Guang Liu, Tao Jin, Chengyu Jiang, George F. Gao, Malik Peiris,2 Hongjie Yu,2 Enfu Chen2 A nosocomial cluster induced by co-infections with avian in- s of January 4, 2016, a novel avian influenza A vi- fluenza A(H7N9) and A(H1N1)pdm09 (pH1N1) viruses oc- Arus, A(H7N9), first identified in China in March curred in 2 patients at a hospital in Zhejiang Province, China, 2013 (1), had caused 676 laboratory-confirmed cases of in January 2014. The index case-patient was a 57-year-old influenza in humans and 275 influenza-associated deaths man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who had been occu- in mainland China (Chinese Center for Disease Control pationally exposed to poultry. He had co-infection with H7N9 and Prevention, unpub. data). Most H7N9 virus infections and pH1N1 viruses. A 71-year-old man with polycythemia vera who was in the same ward as the index case-patient for have been acquired through exposure to live poultry mar- 6 days acquired infection with H7N9 and pH1N1 viruses. The kets (LPMs) in urban settings (2) and have been sporadic, incubation period for the second case-patient was estimated but a few have occurred in clusters of >2 epidemiologi- to be <4 days. -

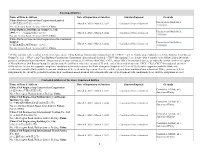

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date

Sanctioned Entities Name of Firm & Address Date of Imposition of Sanction Sanction Imposed Grounds China Railway Construction Corporation Limited Procurement Guidelines, (中国铁建股份有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. Procurement Guidelines, (中铁二十三局集团有限公司)*38 March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited Procurement Guidelines, March 4, 2020 - March 3, 2022 Conditional Non-debarment (中国铁建国际集团有限公司)*38 1.16(a)(ii) No. 40, Fuxing Road, Beijing 100855, China *38 This sanction is the result of a Settlement Agreement. China Railway Construction Corporation Ltd. (“CRCC”) and its wholly-owned subsidiaries, China Railway 23rd Bureau Group Co., Ltd. (“CR23”) and China Railway Construction Corporation (International) Limited (“CRCC International”), are debarred for 9 months, to be followed by a 24- month period of conditional non-debarment. This period of sanction extends to all affiliates that CRCC, CR23, and/or CRCC International directly or indirectly control, with the exception of China Railway 20th Bureau Group Co. and its controlled affiliates, which are exempted. If, at the end of the period of sanction, CRCC, CR23, CRCC International, and their affiliates have (a) met the corporate compliance conditions to the satisfaction of the Bank’s Integrity Compliance Officer (ICO); (b) fully cooperated with the Bank; and (c) otherwise complied fully with the terms and conditions of the Settlement Agreement, then they will be released from conditional non-debarment. If they do not meet these obligations by the end of the period of sanction, their conditional non-debarment will automatically convert to debarment with conditional release until the obligations are met. -

SGS CPSIA Accredited Labs

CPSIA ACCREDITED TESTING LABORATORIES AMERICAS Changzhou SGS-CSTC Standards Technical Services Co. Ltd. Changzhou Branch UNITED STATES 3 F, No.158 Longcheng Avenue SGS – North America Inc. Changzhou 213021, Jiangsu, China 291 Fairfield Avenue, Fairfield, Contact: [email protected] NJ 07004, United States Phone: +86 519 85508607 Contact: [email protected] Accreditor: CNAS (L3533) Phone: +1 973-575-5252 (Ask for CPSC Identification Number: 1388 CPSIA Inquiries) Accreditor: A2LA, IAS (0440.03) CPSC Identification Number: 1020 Guangzhou SGS-CSTC Standards Technical Services Co. Ltd. Guangzhou Branch ENSURE CPSIA COMPLIANCE BRAZIL 198 Kezhu Road, Scientech Park, SGS do Brasil LTDA THANKS TO SGS GLOBAL Guangzhou Economic & Technology Avenida Andromeda, 832 Development District, Guangzhou, EXPERTISE Alphaville, Barueri 06473000, Brazil Guangdong 510663, China Contact: [email protected] Contact: [email protected] As CPSC accredited laboratories, Phone: +55 11 3883 8880 Phone: +86 20 8215 5702 SGS provides comprehensive Accreditor: CGCRE/INMETRO Accreditor: CNAS (L0167) solutions for all products that need to (CRL0049) CPSC Identification Number: 1024 comply with the Consumer Product CPSC Identification Number: 1241 Safety Improvement Act of 2008 Hangzhou (CPSIA). Contact us! MEXICO SGS-CSTC Standards Technical Services SGS Multilab (Mexico) Co., Ltd. Hangzhou Branch Sofocles #217, Col. Los Morales Secc. AMERICAS 5-6/F., No. 4 Building, No. 1180, Bin’an Palmas, Distrito Federal, U.S. (Fairfield, NJ) Road, Huaye Hi-Tech Industrial Park, -

Resistance of House Fly, Musca Domestica L.(Diptera: Muscidae), To

Hindawi Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology Volume 2019, Article ID 4851914, 10 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4851914 Research Article Resistance of House Fly, Musca domestica L. (Diptera: Muscidae), to Five Insecticides in Zhejiang Province, China: The Situation in 2017 Jin-Na Wang, Juan Hou, Yu-Yan Wu, Song Guo, Qin-Mei Liu, Tian-Qi Li, and Zhen-Yu Gong Zhejiang Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 3399 Binsheng Road, Binjiang District, Hangzhou 310051, China Correspondence should be addressed to Zhen-Yu Gong; [email protected] Received 4 March 2019; Revised 4 May 2019; Accepted 19 May 2019; Published 23 June 2019 Academic Editor: Marco Di Luca Copyright © 2019 Jin-Na Wang et al. 0is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Objectives. High dependency on pesticides could cause selection pressure leading to the development of resistance. 0is study was conducted to assess the resistance of the house fly, Musca domestica, to five insecticides, namely, permethrin, deltamethrin, beta- cypermethrin, propoxur, and dichlorvos, in Zhejiang Province. Methods. Field strains of house flies were collected from the 12 administrative districts in Zhejiang Province in 2011, 2014, and 2017, respectively. Topical application method was adopted for the bioassays. 0e probit analysis was used to determine the median lethal doses with the 95% confidence interval, and then the resistance ratio (RR) was calculated. 0e insecticides resistance in different years and the correlations of the resistance between different insecticides were also analyzed. -

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation - Chinese Producers of Wooden Cabinets and Vanities Company Name Company Information Company Name: A Shipping A Shipping Street Address: Room 1102, No. 288 Building No 4., Wuhua Road, Hongkou City: Shanghai Company Name: AA Cabinetry AA Cabinetry Street Address: Fanzhong Road Minzhong Town City: Zhongshan Company Name: Achiever Import and Export Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 103 Taihe Road Gaoming Achiever Import And Export Co., City: Foshan Ltd. Country: PRC Phone: 0757-88828138 Company Name: Adornus Cabinetry Street Address: No.1 Man Xing Road Adornus Cabinetry City: Manshan Town, Lingang District Country: PRC Company Name: Aershin Cabinet Street Address: No.88 Xingyuan Avenue City: Rugao Aershin Cabinet Province/State: Jiangsu Country: PRC Phone: 13801858741 Website: http://www.aershin.com/i14470-m28456.htmIS Company Name: Air Sea Transport Street Address: 10F No. 71, Sung Chiang Road Air Sea Transport City: Taipei Country: Taiwan Company Name: All Ways Forwarding (PRe) Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 268 South Zhongshan Rd. All Ways Forwarding (China) Co., City: Huangpu Ltd. Zip Code: 200010 Country: PRC Company Name: All Ways Logistics International (Asia Pacific) LLC. Street Address: Room 1106, No. 969 South, Zhongshan Road All Ways Logisitcs Asia City: Shanghai Country: PRC Company Name: Allan Street Address: No.188, Fengtai Road City: Hefei Allan Province/State: Anhui Zip Code: 23041 Country: PRC Company Name: Alliance Asia Co Lim Street Address: 2176 Rm100710 F Ho King Ctr No 2 6 Fa Yuen Street Alliance Asia Co Li City: Mongkok Country: PRC Company Name: ALMI Shipping and Logistics Street Address: Room 601 No. -

Hangzhou, China: Hotel Market Overview Market Report - APRIL 2021

Singapore: Hotel Market Market Report - March 2019 MARKET REPORT Hangzhou, China Hotel Market Overview APRIL 2021 Hangzhou, China: Hotel Market Overview Market Report - APRIL 2021 Introduction West Lake/Wulin Square area Hangzhou, the capital and the most populous city of West Lake/Wulin Square area is Hangzhou’s most Zhejiang, has been traditionally known as a tourism city for traditional city center. This area is filled with high-end popular sights including West Lake and Lingyin Temple. shopping malls including Wulin Intime, GDA Plaza and Hangzhou Tower. In recent years, this area is gradually After over 30 years of development, especially after hosting transforming into a smart digital business district with the the G20 summit in 2016, Hangzhou gradually evolved from help of 5G and cloud-based computing technology. a tourism destination to a world-renowned innovation, research and development center backed by the expansion Qianjiang New City of hi-tech companies including Alibaba Group, NetEase, Qianjiang New City is the new Central Business District Huawei and ArcSoft. Hangzhou is attracting high quality situated in the west bank of Qiantang River in Hangzhou. science, technology and ecommerce startups that fill up Following the city’s decision to shift the development multiple business districts around the city. focus from West Lake to Qiantang River since 2001, Qianjiang New City has been strategically focused on the Considering the development of Hangzhou’s old and new development of the tertiary industries such as finance, IT city centers, we have selected the following three sub-hotel and consulting. In 2016, Hangzhou municipal government markets to better understand the overall hotel performance officially moved to the Qianjiang New City. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Results Announcement for the Year Ended December 31, 2020

(GDR under the symbol "HTSC") RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 The Board of Huatai Securities Co., Ltd. (the "Company") hereby announces the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended December 31, 2020. This announcement contains the full text of the annual results announcement of the Company for 2020. PUBLICATION OF THE ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT AND THE ANNUAL REPORT This results announcement of the Company will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism), and the website of the Company (www.htsc.com.cn), respectively. The annual report of the Company for 2020 will be available on the website of London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com), the website of the National Storage Mechanism (data.fca.org.uk/#/nsm/nationalstoragemechanism) and the website of the Company in due course on or before April 30, 2021. DEFINITIONS Unless the context otherwise requires, capitalized terms used in this announcement shall have the same meanings as those defined in the section headed “Definitions” in the annual report of the Company for 2020 as set out in this announcement. By order of the Board Zhang Hui Joint Company Secretary Jiangsu, the PRC, March 23, 2021 CONTENTS Important Notice ........................................................... 3 Definitions ............................................................... 6 CEO’s Letter .............................................................. 11 Company Profile ........................................................... 15 Summary of the Company’s Business ........................................... 27 Management Discussion and Analysis and Report of the Board ....................... 40 Major Events.............................................................. 112 Changes in Ordinary Shares and Shareholders .................................... 149 Directors, Supervisors, Senior Management and Staff.............................. -

Spatial Distribution Pattern of Minshuku in the Urban Agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta

The Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology ISSN 2616-7433 Vol. 3, Issue 1: 23-35, DOI: 10.25236/FSST.2021.030106 Spatial Distribution Pattern of Minshuku in the Urban Agglomeration of Yangtze River Delta Yuxin Chen, Yuegang Chen Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China Abstract: The city cluster in Yangtze River Delta is the core area of China's modernization and economic development. The industry of Bed and Breakfast (B&B) in this area is relatively developed, and the distribution and spatial pattern of Minshuku will also get much attention. Earlier literature tried more to explore the influence of individual characteristics of Minshuku (such as the design style of Minshuku, etc.) on Minshuku. However, the development of Minshuku has a cluster effect, and the distribution of domestic B&Bs is very unbalanced. Analyzing the differences in the distribution of Minshuku and their causes can help the development of the backward areas and maintain the advantages of the developed areas in the industry of Minshuku. This article finds that the distribution of Minshuku is clustered in certain areas by presenting the overall spatial distribution of Minshuku and cultural attractions in Yangtze River Delta and the respective distribution of 27 cities. For example, Minshuku in the central and eastern parts of Yangtze River Delta are more concentrated, so are the scenic spots in these areas. There are also several concentrated Minshuku areas in other parts of Yangtze River Delta, but the number is significantly less than that of the central and eastern regions. Keywords: Minshuku, Yangtze River Delta, Spatial distribution, Concentrated distribution 1. -

Hangzhou Ezviz Technology Co., Ltd

Certificate No: Initial certification date: Valid: 334695-2019-IS-RGC-DNV 07 January, 2020 07 January, 2020 - 25 December, 2021 This is to certify that the management system of Hangzhou Ezviz Software Co., Ltd. 16 / f, Building B, Building 1 No. 555, Qianmo Road, Binjiang District Hangzhou Zhejiang Province China and the sites as mentioned in the appendix accompanying this certificate has been found to conform to the Code of practice for information security controls: ISO/IEC 29151:2017 This certificate is valid for the following scope: The Design, Development, Operation and Maintenance of the EZVIZ Cloud Platform & EZVIZ Cloud Open Platform. Provision of Design, Development, Operation and Maintenance Services for the Internet Software Products of Hangzhou EZVIZ Network Co., Ltd. and Its Overseas Branches and Subsidiaries and Provision of Sales, Management and after Service of the EZVIZ Brand Products and Third-party Products. Provision of Design, Development, Operation and Maintenance Services for Software and Hardware Products of Hangzhou EZVIZ Technology Co., Ltd. Provision of Internet Software Services to End Users and Customers Base on EZVIZ Hardware Products and Third-party Hardware Products which is Complying with the EZVIZ’s Equipment Internet of Things (IOT) Protocol. Apply Standard ISO29151:2017(Code of Practice for Personally Identifiable Information Protection.) For above Services. This is in accordance with the Latest Version Statement of Applicability, Version 2.0 Place and date: For the issuing office: Shanghai, 07 January, 2020 DNV GL – Business Assurance Suite A, Building 9, No.1591 Hongqiao Road, Changning District, Shanghai 200336, P.R. China TEL: +86 21 32799000 Zhu Hai Ming Management Representative Lack of fulfilment of conditions as set out in the Certification Agreement may render this Certificate invalid. -

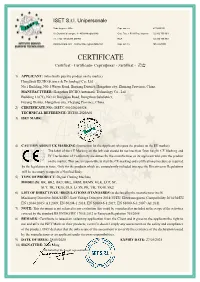

CERTIFICATE Certificat - Certificado- Сертификат - Zertifikat - 證書

ISET S.r.l. Unipersonale Sede Legale e Uffici Cap. soc. i.v. € 10.200,00 Via Donatori di sangue, 9 - 46024 Moglia (MN) Cod. Fisc. e P.IVA Reg. Imprese 02 332 750 369 Tel. e fax +39 (0)376 598963 REA 02 332 750 369 www.iset-italia.com [email protected] Cap. soc. i.v. MN 0221098 CERTIFICATE Certificat - Certificado- Сертификат - Zertifikat - 證書 1) APPLICANT: (who finally puts the product on the market) Hangzhou IECHO Science & Technology Co., Ltd No.1 Building, NO.1 Weiye Road, Binjiang District, Hangzhou city, Zhejiang Province, China. MANUFACTURER: Hangzhou IECHO Automatic Technology Co., Ltd Building 11(C1), NO.20 Dongqiao Road, Dongzhou Subdistrict, Fuyang District, Hangzhou city, Zhejiang Province, China. 2) CERTIFICATE NO.: ISETC.001020200528 TECHNICAL REFERENCE: IECHO-2020A01 3) ISET MARK: 4) CAUTION ABOUT CE MARKING (Instruction for the Applicant who puts the product on the EU market): The label of the CE Marking on the left side should be not less than 5mm height. CE Marking and EC Declaration of Conformity are duties for the manufacturer or its applicant who puts the product on the market. This one is responsible to start the CE marking and certification procedure as required by the legislation in force. Only for the products which are compulsorily included into specific Directives or Regulations will be necessary to appoint a Notified Body. 5) TYPE OF PRODUCT: Digital Cutting Machine MODEL(S): BK, BK2, BK3, BKL, BKM, BKMS, GLK, LCP, SC, SCT, TK, TK3S, GLS, LCPS, PK, VK, TK4S, SK2 6) LIST OF DIRECTIVES / REGULATIONS /STANDARDS (as declared by the manufacturer itself) Machinery Directive 2006/42/EC, Low Voltage Directive 2014/35/EU, Electromagnetic Compatibility 2014/30/EU EN 12044:2005+A1:2009; EN 60204-1:2018, EN 61000-6-1:2019, EN 61000-6-3:2007+A1:2011 7) NOTE: This document is not referred to any evaluation that could be considered as included in the scope of the activities covered by the standard BS EN ISO/IEC 17065:2012 or European Regulation 765/2008. -

Hz15090034a-17A21DIM827GU24

Report No.: HZ15090034a Test Summary Sample Tested: 17A21DIM/827/GU24 Luminous Efficacy Total Luminous Flux Power Power Factor (Lumens /Watt) (Lumens) (Watts) 105.9 1710.8 16.15 0.9341 CCT Stabilization Time CRI (K) (Light & Power) 2638 81.5 65 Table 1: Executive Data Summary Note: The above results are recorded/ derived from measurements made using an Integrating Sphere. Test specifications: Date of Receipt : Sep. 30, 2014 Date of Test : Oct. 10, 2014 to Oct. 11, 2014 Test item : Total Luminous Flux, Luminous Distribution Intensity, Luminous Efficacy, Correlated Color Temperature, Color Rendering Index, Chromaticity Coordinate, Electrical parameters Reference Standard : IESNA LM-79-2008 Approved Method for the Electrical and Photometric Measurements of Solid-State Lighting Products Prepared by: Leading Testing Laboratories Page 2 of 13 No.1805, DongLiu road, BinJiang District, Hangzhou, China Tel: +86-571-56680806 www.ledtestlab.com Report No.: HZ15090034a TABLE OF CONTENT LM-79-08 Test Report ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Test Summary......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Sample Photo .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 TEST RESULTS ...................................................................................................................................................