Sonic Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comprehensive History of Techno and Finding God in the Music with Ellen Allien

Editorial A Comprehensive History of Techno and Finding God in the Music With Ellen Allien Kian McHugh | August 3, 2020 When my Zoom call with Ellen Allien connects, at last, I feel weeks of anticipation turn to uncontrollable excitement. My fingers, sweaty from nerves, and a poorly brewed Starbucks coffee, type out the instructions on how to get her audio configured. Ellen is lounging in her Ibiza flat where she has painted all of the walls completely black so that when the sun shines through her window, the room glows yellow. The first fully formed thought I could pencil down was that her posture seemed to denote a sincere attention to detail and confidence in comfort that most others lack. For the first 2 minutes of the call, we both instinctively laugh, muted, and unaware that our discussion of Techno would soon gravitate toward, and then find unexpected momentum in… a deep consideration of Techno, God, and religion. “Rap is where you rst heard it… If rap is more an American phenomenon, techno is where it all comes together in Europe as producers and musicians engage in a dialogue of dazzling speed.” – Jon Savage (English writer, broadcaster and music journalist). In Hanif Abdurraqib’s 2019 book, Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest, he so beautifully praises “the low end” of a track: “The feeling of something familiar that sits so deep in your chest that you have to hum it out … where the bass and the kick drums exist.” His point rings true across all music that is heavily percussion driven. -

Crossing Over: from Black Rhythm Blues to White Rock 'N' Roll

PART2 RHYTHM& BUSINESS:THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF BLACKMUSIC Crossing Over: From Black Rhythm Blues . Publishers (ASCAP), a “performance rights” organization that recovers royalty pay- to WhiteRock ‘n’ Roll ments for the performance of copyrighted music. Until 1939,ASCAP was a closed BY REEBEEGAROFALO society with a virtual monopoly on all copyrighted music. As proprietor of the com- positions of its members, ASCAP could regulate the use of any selection in its cata- logue. The organization exercised considerable power in the shaping of public taste. Membership in the society was generally skewed toward writers of show tunes and The history of popular music in this country-at least, in the twentieth century-can semi-serious works such as Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, Cole Porter, George be described in terms of a pattern of black innovation and white popularization, Gershwin, Irving Berlin, and George M. Cohan. Of the society’s 170 charter mem- which 1 have referred to elsewhere as “black roots, white fruits.’” The pattern is built bers, six were black: Harry Burleigh, Will Marion Cook, J. Rosamond and James not only on the wellspring of creativity that black artists bring to popular music but Weldon Johnson, Cecil Mack, and Will Tyers.’ While other “literate” black writers also on the systematic exclusion of black personnel from positions of power within and composers (W. C. Handy, Duke Ellington) would be able to gain entrance to the industry and on the artificial separation of black and white audiences. Because of ASCAP, the vast majority of “untutored” black artists were routinely excluded from industry and audience racism, black music has been relegated to a separate and the society and thereby systematically denied the full benefits of copyright protection. -

Native Instruments Releases the Second Installment in the EVERYBODY DJ Video Series

Native Instruments releases the second installment in the EVERYBODY DJ video series Dance music pioneer A Guy Called Gerald discusses the cultural link between new technology and the evolution of electronic music Berlin, September 18, 2014 – Native Instruments today continues the EVERYBODY DJ video series with the second installment featuring electronic music legend A Guy Called Gerald. The video features Gerald describing how innovative technology plays an important role in defining DJ culture and how mobile apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone are creating new performance possibilities and diversifying relationships to digital music. An icon in his own league, A Guy Called Gerald has been an instrumental figure in the development of techno, acid house, jungle, and drum and bass in the UK since the late 1980s. The video captures Gerald’s view on the close relationship between technology and electronic music – reflecting on previous audio limitations with vinyl, and how digital technology has changed how he listens to, DJs, and creates music. Filmed in London at the premier of RELEASE, a documentary on House Shuffling in Britain, the video shows Gerald as he explains why the physical manipulation of waveforms on apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone has given rise to completely new ways of DJing. Gerald can be seen mixing, beat jumping, and loop slicing live with TRAKTOR DJ for iPad – a tool that has had a particular impact on his DJing. Still underway, the first video in the EVERYBODY DJ series introduced the MIX. WIN. BERLIN! competition where Native Instruments asks “What would you play?” Anyone can enter to win a VIP weekend in Berlin by recording and uploading a mix to Mixcloud using TRAKTOR DJ, and tagging it with the #whatwouldyouplay hashtag. -

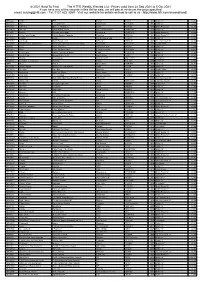

2021 Hard to Find the HTFR Weekly Wanted List

© 2021 Hard To Find The HTFR Weekly Wanted List - Prices valid from 28 Sep 2021 to 5 Oct 2021 If you have any of the records in this list for sale, we will pay at minimum the price specified email: [email protected] - Tel: 0121 622 3269 - Visit our website for details on how to sell to us - http://www.htfr.com/secondhand/ MR26666 100Hz EP3 Pacific FIC020 1999 British 12" £4.00 MR75274 16B Trail Of Dreams Stonehouse STR12008 1995 British 12" £2.00 MR18837 2 Funky 2 Brothers And Sisters Logic FUNKY2 1994 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR759025 3rd Core Mindless And Broken WEA International Inc. SAM00291 2000 British 12" £2.00 MR12656 4 Hero Cooking Up Ya Brain Reinforced RIVET1216 1992 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR14089 A Guy Called Gerald 28 Gun Badboy / Paranoia Columbia XPR1684 1992 British Promo 12" £8.00 MR169958 A Sides Punks Strictly Underground STUR74 1996 British 12" £4.00 MR353153 Aaron Carl Down (Resurrected) Wallshaker WMAC30 2009 American Import 12" £2.00 MR759966 Academy Of St. Martin-in-the-F Amadeus (Original Soundtrack Recording) Metronome 8251261ME 1984 Double Album £2.00 MR4926 Acen Close Your Eyes Production House PNT034 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR12863 Acen Trip Ii The Moon Part 3 Production House PNT042RX 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR16291 Age Of Love Age Of Love (Jam & Spoon) React 12REACT9 1992 British 12" £7.00 MR44954 Agent Orange Sounds Flakey To Me Agent Orange AO001 1992 British 12" £8.00 MR764680 Akasha Cinematique Wall Of Sound WALLLP016 1998 Vinyl Album £1.00 MR42023 Alan Braxe & Fred Falke Running Vulture VULT001 2000 French -

“Bo Diddley” and “I'm a Man” (1955)

“Bo Diddley” and “I’m a Man” (1955) Added to the National Registry: 2011 Essay by Ed Komara (guest post)* Bo Diddley While waiting in Bo Diddley’s house to conduct an interview for the February 12, 1987 issue of “Rolling Stone,” journalist Kurt Loder noticed a poster. “If You Think Rock and Roll Started With Elvis,” it proclaimed, “You Don’t Know Diddley.” This statement seems exaggerated, but upon listening to Diddley’s April 1955 debut 78 on Checker 814, “Bo Diddley” backed with “I’m A Man,” it becomes apt, perhaps even understated. Bo Diddley (1928-2008) described his own place in music history to Loder. “People wouldn’t even bother with no stuff like ‘Bo Diddley’ and ‘I’m A Man’ and stuff like that ten years earlier [circa 1945] or even a year earlier [1954]. Then Leonard and Phil Chess decided to take a chance, and suddenly a whole different scene, a different kind of music, came in. And that was the beginning of rock and roll.” The composer credit for Checker 814 reads “E. McDaniels,” and there begins the tale. Bo Diddley was born Ellas Otha Bates in McComb, Mississippi on December 30, 1928 to a teenage mother and her local boyfriend. He was raised, however, by his maternal first cousin, Gussie McDaniel, to whom he was taken to Chicago, and given her surname McDaniel. He grew up on the South Side of the city, where he learned violin, trombone and, at age 12, the guitar. Before long, he was playing for change on the local streets. -

Music Business in Detroit

October 18, 2013 Music Business in Detroit: Estimating the Size of the Music Industry in the Motor City Prepared by: Anderson Economic Group, LLC Colby Spencer Cesaro, Senior Analyst Alex Rosaen, Senior Consultant Lauren Branneman, Senior Analyst Forward by: Patrick L. Anderson, Principal & CEO Anderson Economic Group, LLC 1555 Watertower Place, Suite 100 East Lansing, Michigan 48823 Tel: (517) 333-6984 Fax: (517) 333-7058 www.AndersonEconomicGroup.com © Anderson Economic Group, LLC, 2013 Permission to reproduce in entirety granted with proper citation. All other rights reserved. Foreword I'm pleased to share with readers of Crain's Detroit Business, as well as with others in the Detroit region, this first-of-its-kind study of the business of music in southeast Michigan. Everyone that grew up in this area knows of the "Motown sound," as well as the heritage of jazz, blues, and rock that has steeped into our culture. Many of us are also aware of the more recent innovations of techno and hip-hop, much of which has roots in Detroit. However, until now there has been no systematic analysis of the business of music in our area. Our Anderson Economic Group consultants have combed census and other business records; examined the geographic pattern of nightclubs and perfor- mance venues; scanned demographic patterns for concentrations of heavy enter- tainment consumers; and even conducted primary research into the days/nights of live music available to metro Detroiters at over two hundred specific bars, taverns, and clubs. What we have assembled is a thorough analysis of an indus- try that has always been important to our culture, but can now also be known for its contributions to our employment and earnings. -

Motown the Musical

EDUCATIONAL GUIDE C1 Kevin MccolluM Doug Morris anD Berry gorDy Present Book by Music and Lyrics from Berry gorDy The legenDary MoTown caTalog BaseD upon The BooK To Be loveD: Music By arrangeMenT wiTh The Music, The Magic, The MeMories sony/aTv Music puBlishing of MKoevinTown B yM Bcerrycollu gorDyM Doug Morris anD Berry gorDy MoTown® is a regisTereD TraPresentDeMarK of uMg recorDings, inc. Starring BranDon vicTor Dixon valisia leKae charl Brown Bryan Terrell clarK Book by Music and Lyrics from TiMoThy J. alex Michael arnolD nicholas chrisTopher reBecca e. covingTon ariana DeBose anDrea Dora presTBonerry w. Dugger g iiior Dwyil Kie ferguson iii TheDionne legen figgins DaryMarva M hicoKsT ownTiffany c JaaneneTalog howarD sasha huTchings lauren liM JacKson Jawan M. JacKson Morgan JaMes John Jellison BaseD upon The BooK To Be loveD: Music By arrangeMenT wiTh crysTal Joy Darius KaleB grasan KingsBerry JaMie laverDiere rayMonD luKe, Jr. Marielys Molina The Music, The Magic, The MeMories sony/aTv Music puBlishing syDney MorTon Maurice Murphy Jarran Muse Jesse nager MilTon craig nealy n’Kenge DoMinic nolfi of MoTown By Berry gorDy saycon sengBloh ryan shaw JaMal sTory eric laJuan suMMers ephraiM M. syKes ® JMuliusoTown Tho isM asa regisiii TereDanielD Tra DJ.eM waraTTK sof uMDgonal recorD wDeingsBBer, i, ncJr.. Scenic Design Costume Design LighStarringting Design Sound Design Projection Design DaviD Korins esosa BranDnonaTasha vic TKoraTz Dixon peTer hylensKi Daniel BroDie Casting Hair & Wig Design valisia leKae Associate Director Assistant Choreographer Telsey + coMpany charlcharles Brown g. lapoinTe scheleBryan willia TerrellMs clarK Brian h. BrooKs BeThany Knox,T icsaMoThy J. alex Michael arnolD nicholas chrisTopher reBecca e. -

Detroit: Techno City 27 July – 25 September 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room Preview 26 July

ICA Press release: 26 May 2016 Detroit: Techno City 27 July – 25 September 2016 ICA Fox Reading Room Preview 26 July Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit (1988). Courtesy Neil Rushton and 10 Records LTD The next ICA Fox Reading Room exhibition will present a studied look at the evolution and subsequent dispersion of ‘Detroit Techno music’. This term, coined in the late 1980s, reflects the musical and social influences that informed early experiments merging sounds of synth-pop and disco with funk to create this distinct music genre. For the first time in the UK, a dedicated exhibition will chart a timeline of ‘Detroit Techno music’ from its 1970s origins, continuing through to the early 1990s. The genre’s origins begin in the disco parties of Ken Collier with influence from local radio stations and DJs, such as Electrifying Mojo and The Wizard (aka Jeff Mills). The ICA’s exhibition explores how a generation was inspired to create a new kind of electronic music that was evidenced in the formative UK compilation: Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit. Using inexpensive analogue technology, such as the Roland TR 808 and 909, DJs and producers including Juan Atkins, Blake Baxter, Eddie Fowlkes, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson, formed this seminal music genre. Although the music failed to gain mainstream audiences in the U.S, it became a phenomenon in Europe. This success established Detroit Techno, as a new strand of music which absorbed exterior European tastes and influences. This introduced a second wave of DJs and producers to the sound including Carl Craig, Richie Hawtin and Kenny Larkin. -

Detroit : Techno

Until recently, Detroit has not had much attention at all con cerning its role as the birthplace of techno. "Detroit, globally known as the birthplace of techno, is virtually unrecognized nationally and locally beyond its Motown and rock roots". It DETROIT: TECHNO has always existed as such under the popular culture radar. First and foremost, why was Detroit the breeding ground for techno music? Why has the general population taken so long in recognizing Detroit for its techno accomplishments? Could it be simply because Detroit is not a mega-city like New York or Los Angeles? Or is it simply because the time and the place ]ohnathan Bowen were not right until recently? The Belleville 3: Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Detroit has long been known by many names: Motown, the Saunderson, arc the three individuals who are credited as Motor City, Hockey Town, and even the less than flattering techno's creators. These three individuals grew up in Murder City. However, with the passing of time and the dim Belleville, hence the term "The Belleville 3," but they later ming and brightening of trends, Detroit would come to be moved into Detroit to carry on their pioneering work in the known by another name: TechnoTown. \Vhat is techno? Upon 1980's and beyond. Atkins, May, and Saunderson didn't actu opening an Encyclopedia Britannica and looking under the ally begin this pioneering work of creating techno in Detroit entry labeled "Techno," one will find this encompassing and however. Juan Atkins sums it up best: "vVhen I first started revealing definition: making music, I lived in Detroit. -

The Social and Cultural Changes That Affected the Music of Motown Records from 1959-1972

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2015 The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 Lindsey Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Lindsey, "The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 195. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/195 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 by Lindsey Baker A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the degree of Bachelor of Music in Performance Schwob School of Music Columbus State University Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Kevin Whalen Honors Committee Member ^ VM-AQ^A-- l(?Yy\JcuLuJ< Date 2,jbl\5 —x'Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz Dean of the Honors College ((3?7?fy/L-Asy/C/7^ ' Date Dr. Cindy Ticknor Motown Records produced many of the greatest musicians from the 1960s and 1970s. During this time, songs like "Dancing in the Street" and "What's Going On?" targeted social issues in America and created a voice for African-American people through their messages. Events like the Mississippi Freedom Summer and Bloody Thursday inspired the artists at Motown to create these songs. Influenced by the cultural and social circumstances of the Civil Rights Movement, the musical output of Motown Records between 1959 and 1972 evolved from a sole focus on entertainment in popular culture to a focus on motivating social change through music. -

Manor Primary School Music Year 1: in the Grove Overview of the Learning: All the Learning Is Focused Around One Song: in the Groove

Manor Primary School Music Year 1: In The Grove Overview of the Learning: All the learning is focused around one song: In The Groove. The material presents an integrated approach to music where games, the interrelated dimensions of music (pulse, rhythm, pitch etc.), singing and playing instruments are all linked. Core Aims Pupils should be taught How to listen to music. perform, listen to, review and evaluate music across a range of historical periods, genres, styles and To sing a range of songs song. traditions, including the works of the great composers and musicians To understand the geographical origin of the music and in which era it was composed. Learn to sing and to use their voices, to create and compose music on their own and with others, To experience and learn how to apply key musical concepts/elements, eg finding a pulse, clapping have the opportunity to learn a musical instrument, use technology appropriately and have the a rhythm, use of pitch. opportunity to progress to the next level of musical excellence To play the accompanying instrumental parts (optional). understand and explore how music is created, produced and communicated, including through the inter-related dimensions: pitch, duration, dynamics, tempo, timbre, texture, structure and To work together in a band/ensemble. appropriate musical notations. To develop creativity through improvising and composing within the song. To understand and use the first five notes of C Major scale while improvising and composing. To experience links to other areas of the curriculum To recognise the style of the music and to understand its main style indicators. -

Allegories of Afrofuturism in Jeff Mills and Janelle Monaé

Vessels of Transfer: Allegories of Afrofuturism in Jeff Mills and Janelle Monáe Feature Article tobias c. van Veen McGill University Abstract The performances, music, and subjectivities of Detroit techno producer Jeff Mills—radio turntablist The Wizard, space-and-time traveller The Messenger, founding member of Detroit techno outfit Underground Resistance and head of Axis Records—and Janelle Monáe—android #57821, Cindi Mayweather, denizen and “cyber slavegirl” of Metropolis—are infused with the black Atlantic imaginary of Afrofuturism. We might understand Mills and Monáe as disseminating, in the words of Paul Gilroy, an Afrofuturist “cultural broadcast” that feeds “a new metaphysics of blackness” enacted “within the underground, alternative, public spaces constituted around an expressive culture . dominated by music” (Gilroy 1993: 83). Yet what precisely is meant by “blackness”—the black Atlantic of Gilroy’s Afrodiasporic cultural network—in a context that is Afrofuturist? At stake is the role of allegory and its infrastructure: does Afrofuturism, and its incarnates, “represent” blackness? Or does it tend toward an unhinging of allegory, in which the coordinates of blackness, but also those of linear temporality and terrestial subjectivity, are transformed through becoming? Keywords: Afrofuturism, Afrodiaspora, becoming, identity, representation, race, android, alien, Detroit techno, Janelle Monáe tobias c. van Veen is a writer, sound-artist, technology arts curator and turntablist. Since 1993 he has organised interventions, publications, gatherings, exhibitions and broadcasts around technoculture, working with MUTEK, STEIM, Eyebeam, the New Forms Festival, CiTR, Kunstradio and as Concept Engineer and founder of the UpgradeMTL at the Society for Arts and Technology (SAT). His writing has appeared in many publications.