The Hydraulic Architecture of Conifers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinus Cembra

Pinus cembra Pinus cembra in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats G. Caudullo, D. de Rigo Arolla or Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra L.) is a slow-growing, long lived conifer that grows at high altitudes (up to the treeline) with continental climate and is able to resist to very low winter temperature. It has large edible seeds which are dispersed principally by the European nutcracker. The timber is strong and of good quality but it is not a commercially important species because of its slow growth rate and frequent contorted shape. This pine is principally used to protect slopes and valleys against avalanches and soil erosion. In alpine habitats it is threatened principally by tourism development, even if the recent reduction of mountain pasture activities is allowing this pine to return in many areas. Pinus cembra L., known as Arolla pine or Swiss stone pine, is a slow growing, small to medium-sized evergreen conifer (10- Frequency 12 m height, occasionally 20-25 m), which can live up to 1000 < 25% 25% - 50% 1-5 years . The crown is densely conical when young, becoming 50% - 75% cylindrical and finally very open6. It grows commonly in a curved > 75% Chorology or contorted shape, but in protected areas can grow straight and Native to considerable sizes. Needles are in fascicles of five, 5-9 cm long1, 7. Arolla pine is a monoecious species and the pollination is driven by wind3. Seed cones appear after 40-60 years, they Seed cones are purplish in colour when maturing. are 4-8 cm long and mature in 2 years3, 6. -

Gradient Analysis of Exotic Species in Pinus Radiata Stands of Tenerife (Canary Islands) S

The Open Forest Science Journal, 2009, 2, 63-69 63 Open Access Gradient Analysis of Exotic Species in Pinus radiata Stands of Tenerife (Canary Islands) S. Fernández-Lugo and J.R. Arévalo* Departamento de Ecología, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de La Laguna, La Laguna 38206, Spain Abstract: Identifying the factors that influence the spread of exotic species is essential for evaluating the present and future extent of plant invasions and for the development of eradication programs. We randomly established a network of 250 plots on an exotic Pinus radiata D. Don plantation on Tenerife Island in order to determine if roads and urban centers are favouring the spread of exotic plant species into the forest. We identified four distinct vegetation groups in the P. radiata stands: advanced laurel forest (ALF), undeveloped laurel forest (ULF), ruderal (RU), and Canarian pine stand (CPS). The groups farthest from roads and urban nuclei (ALF and CPS) have the best conserved vegetation, characterizing by the main species of the potential vegetation of the area and almost no exotic and ruderal species. On the other hand, the groups nearest to human infrastructures (ULF and RU) are characterized by species from potential vegetation’s substitution stages and a higher proportion of exotic and ruderal species. The results indicate distance to roads and urban areas are disturbance factors favouring the presence of exotic and ruderal species into the P. radiata plantation. We propose the eradication of some dangerous exotic species, monitoring of the study area in order to detect any intrusion of alien species in the best conserved areas and implementation of management activities to reduce the perturbation of the ULF and RU areas. -

Carbon Sequestration in Managed Temperate Coniferous Forests Under Climate Change

Biogeosciences, 13, 1933–1947, 2016 www.biogeosciences.net/13/1933/2016/ doi:10.5194/bg-13-1933-2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Carbon sequestration in managed temperate coniferous forests under climate change Caren C. Dymond1, Sarah Beukema2, Craig R. Nitschke3, K. David Coates1, and Robert M. Scheller4 1Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, Government of British Columbia, Victoria, Canada 2ESSA Technologies Ltd., Vancouver, Canada 3School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, University of Melbourne, Richmond, Australia 4Department of Environmental Science and Management, Portland State University, Portland, USA Correspondence to: Caren C. Dymond ([email protected]) Received: 16 November 2015 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 21 December 2015 Revised: 11 March 2016 – Accepted: 16 March 2016 – Published: 30 March 2016 Abstract. Management of temperate forests has the poten- 1 Introduction tial to increase carbon sinks and mitigate climate change. However, those opportunities may be confounded by nega- tive climate change impacts. We therefore need a better un- As a global society, we depend on forests and land to take −1 derstanding of climate change alterations to temperate for- up about 2.5 C 1.3 PgC yr , about one-third of our fossil est carbon dynamics before developing mitigation strategies. emissions (Ciais et al., 2013). A reduction in the size of The purpose of this project was to investigate the interac- these sinks could accelerate global change by further increas- tions of species composition, fire, management, and climate ing the accumulation rate of greenhouse gases in the atmo- change in the Copper–Pine Creek valley, a temperate conifer- sphere. -

Shrubl Maritime Juniper Woodland/Shrubland

Maritime Juniper Woodland/ShrublWoodland/Shrublandand State Rank: S1 – Critically Imperiled The Maritime Juniper Woodland/ substrate stability; even Shrubland is a predominantly evergreen in stable situations community within the coastal salt spray community edges may zone; The trees tend to be short (less not be clear. Different than 15 feet) and scattered, with the types of communities tops sculpted by winds and salt spray; grade into and interdigitate with each forests, in areas of continuous changes of other. Very small patches levels of salt spray and substrate types. of any type within The dominant species is eastern red cedar another community (also called juniper), though the should be considered to Maritime Juniper Woodland/Shrubland above a abundance of red cedar is highly variable. be part of the variation of salt marsh. Photo: Patricia Swain, NHESP. It grows in association with scattered trees the main community. Description: Maritime Juniper and shrubs typical of the surrounding Maritime Pitch Pine Woodland/Shrublands occur on and vegetation such as pitch pine, various Woodlands on Dunes are between sand dunes, on the upper edges oaks, black cherry, red maple, blueberries, dominated by pitch pine. Maritime provide habitat for shrubland nesting birds of salt marshes and on cliffs and rocky huckleberries, sumac, and very often, Shrubland communities are dominated by and are important as feeding and resting/ headlands: all areas receiving salt spray poison ivy. Green briar can be abundant in a dense mixture of primarily deciduous roosting areas for migrating birds. from high winds. The maritime juniper more established woodlands, particularly shrubs, but may include red cedar. -

Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area Gap Analysis

United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area Gap Analysis Analyses and recommendations in view of the 10% target for forest protection under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) 2nd revised edition, January 2009 Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area Gap Analysis Analyses and recommendations in view of the 10% target for forest protection under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Report prepared by: United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC) World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Network World Resources Institute (WRI) Institute of Forest and Environmental Policy (IFP) University of Freiburg Freiburg University Press 2nd revised edition, January 2009 The United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP- WCMC) is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the world's foremost intergovernmental environmental organization. The Centre has been in operation since 1989, combining scientific research with practical policy advice. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services to help decision makers recognize the value of biodiversity and apply this knowledge to all that they do. Its core business is managing data about ecosystems and biodiversity, interpreting and analysing that data to provide assessments and policy analysis, and making the results -

Stuart, Trees & Shrubs

Excerpted from ©2001 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. May not be copied or reused without express written permission of the publisher. click here to BUY THIS BOOK INTRODUCTION HOW THE BOOK IS ORGANIZED Conifers and broadleaved trees and shrubs are treated separately in this book. Each group has its own set of keys to genera and species, as well as plant descriptions. Plant descriptions are or- ganized alphabetically by genus and then by species. In a few cases, we have included separate subspecies or varieties. Gen- era in which we include more than one species have short generic descriptions and species keys. Detailed species descrip- tions follow the generic descriptions. A species description in- cludes growth habit, distinctive characteristics, habitat, range (including a map), and remarks. Most species descriptions have an illustration showing leaves and either cones, flowers, or fruits. Illustrations were drawn from fresh specimens with the intent of showing diagnostic characteristics. Plant rarity is based on rankings derived from the California Native Plant Society and federal and state lists (Skinner and Pavlik 1994). Two lists are presented in the appendixes. The first is a list of species grouped by distinctive morphological features. The second is a checklist of trees and shrubs indexed alphabetically by family, genus, species, and common name. CLASSIFICATION To classify is a natural human trait. It is our nature to place ob- jects into similar groups and to place those groups into a hier- 1 TABLE 1 CLASSIFICATION HIERARCHY OF A CONIFER AND A BROADLEAVED TREE Taxonomic rank Conifer Broadleaved tree Kingdom Plantae Plantae Division Pinophyta Magnoliophyta Class Pinopsida Magnoliopsida Order Pinales Sapindales Family Pinaceae Aceraceae Genus Abies Acer Species epithet magnifica glabrum Variety shastensis torreyi Common name Shasta red fir mountain maple archy. -

Pines in the Arboretum

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MtJ ARBORETUM REVIEW No. 32-198 PETER C. MOE Pines in the Arboretum Pines are probably the best known of the conifers native to The genus Pinus is divided into hard and soft pines based on the northern hemisphere. They occur naturally from the up the hardness of wood, fundamental leaf anatomy, and other lands in the tropics to the limits of tree growth near the Arctic characteristics. The soft or white pines usually have needles in Circle and are widely grown throughout the world for timber clusters of five with one vascular bundle visible in cross sec and as ornamentals. In Minnesota we are limited by our cli tions. Most hard pines have needles in clusters of two or three mate to the more cold hardy species. This review will be with two vascular bundles visible in cross sections. For the limited to these hardy species, their cultivars, and a few hy discussion here, however, this natural division will be ignored brids that are being evaluated at the Arboretum. and an alphabetical listing of species will be used. Where neces Pines are readily distinguished from other common conifers sary for clarity, reference will be made to the proper groups by their needle-like leaves borne in clusters of two to five, of particular species. spirally arranged on the stem. Spruce (Picea) and fir (Abies), Of the more than 90 species of pine, the following 31 are or for example, bear single leaves spirally arranged. Larch (Larix) have been grown at the Arboretum. It should be noted that and true cedar (Cedrus) bear their leaves in a dense cluster of many of the following comments and recommendations are indefinite number, whereas juniper (Juniperus) and arborvitae based primarily on observations made at the University of (Thuja) and their related genera usually bear scalelikie or nee Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, and plant performance dlelike leaves that are opposite or borne in groups of three. -

EVIDENCE for AUXIN REGULATION of BORDERED-PIT POSITIONING DURING TRACHEID DIFFERENTIATION in LARIX LARICINA By

IAWA Journal, Vol. 16 (3),1995: 289-297 EVIDENCE FOR AUXIN REGULATION OF BORDERED-PIT POSITIONING DURING TRACHEID DIFFERENTIATION IN LARIX LARICINA by Mathew Adam Leitch & Rodney Arthur Savidge 1 Faculty of Forestry and Environmental Management, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick, E3B 6C2, Canada SUMMARY Chips containing cambium intact between xylem and phloem were cut from 8-year-old stem regions of 20-30-year-old dormant Larix laricina in late spring and cultured under controlled conditions for six weeks on a defined medium containing varied concentrations of I-naphthalene acetic acid (NAA, a synthetic auxin). Microscopy revealed that auxin was essential for cambial growth and tracheid differentiation. Low (0.1 mg/l) and high (10.0 mg/l) auxin concentrations were conducive to bordered pits forming in tangential walls, whereas an intermediate concentration (1.0 mg/l) of NAA favoured positioning of pits in radial walls. INTRODUCTION Two decades ago, Barnett and Harris (1975) pointed out that the processes involved in bordered-pit formation were incompletely understood, in particular the way in which the pit site is determined and how adjoining cells form a perfectly symmetrical bor dered-pit pair. Observing that radial walls of enlarging cambial derivatives were vari ably thick and thin, Barnett and Harris (1975) advanced the hypothesis that bordered pit development occurs at sites where the primary wall is thinned through the process of centrifugal displacement of microfibrils. Others, however, considered that a thick ening rather than a thinning of the primary wall was indicative of the site where pit development commenced (FengeI1972; Parham & Baird 1973). -

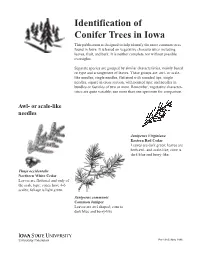

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This Publication Is Designed to Help Identify the Most Common Trees Found in Iowa

Identification of Conifer Trees in Iowa This publication is designed to help identify the most common trees found in Iowa. It is based on vegetative characteristics including leaves, fruit, and bark. It is neither complete nor without possible oversights. Separate species are grouped by similar characteristics, mainly based on type and arrangement of leaves. These groups are; awl- or scale- like needles; single needles, flattened with rounded tips; single needles, square in cross section, with pointed tips; and needles in bundles or fasticles of two or more. Remember, vegetative character- istics are quite variable; use more than one specimen for comparison. Awl- or scale-like needles Juniperus Virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Leaves are dark green; leaves are both awl- and scale-like; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Thuja occidentalis Northern White Cedar Leaves are flattened and only of the scale type; cones have 4-6 scales; foliage is light green. Juniperus communis Common Juniper Leaves are awl shaped; cone is dark blue and berry-like. Pm-1383 | May 1996 Single needles, flattened with rounded tips Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas Fir Needles occur on raised pegs; 3/4-11/4 inches in length; cones have 3-pointed bracts between the cone scales. Abies balsamea Abies concolor Balsam Fir White (Concolor) Fir Needles are blunt and notched at Needles are somewhat pointed, the tip; 3/4-11/2 inches in length. curved towards the branch top and 11/2-3 inches in length; silver green in color. Single needles, Picea abies Norway Spruce square in cross Needles are 1/2-1 inch long; section, with needles are dark green; foliage appears to droop or weep; cone pointed tips is 4-7 inches long. -

The Effects of Sulphur Dioxide on Selected Hepatics" (1978)

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1978 The ffecE ts of Sulphur Dioxide on Selected Hepatics Steven L. Gatchel Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Botany at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Gatchel, Steven L., "The Effects of Sulphur Dioxide on Selected Hepatics" (1978). Masters Theses. 3192. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3192 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPF-:R CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a ' number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date Author I respectfully request Booth Library of .Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because---------------- Date Author pdm THE EFFECTS OF SULPHUR DIOXIDE ON SELECTED HEPATICS (TITLE} BY Steven L. Gatchel THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1978 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE ol}-~ d2/, 19"/f DATE ADVISER I/ 'Ouue~2\ 1\l~ DATE ' ~RTMENT WHEAD THE EFFECTS OF SULPHUR DIOXIDE ON SELECTED HEPATICS BY STEVEN L. -

Aquatic and Wet Marchantiophyta, Order Metzgeriales: Aneuraceae

Glime, J. M. 2021. Aquatic and Wet Marchantiophyta, Order Metzgeriales: Aneuraceae. Chapt. 1-11. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte 1-11-1 Ecology. Volume 4. Habitat and Role. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 11 April 2021 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 1-11: AQUATIC AND WET MARCHANTIOPHYTA, ORDER METZGERIALES: ANEURACEAE TABLE OF CONTENTS SUBCLASS METZGERIIDAE ........................................................................................................................................... 1-11-2 Order Metzgeriales............................................................................................................................................................... 1-11-2 Aneuraceae ................................................................................................................................................................... 1-11-2 Aneura .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1-11-2 Aneura maxima ............................................................................................................................................................ 1-11-2 Aneura mirabilis .......................................................................................................................................................... 1-11-7 Aneura pinguis .......................................................................................................................................................... -

How Trees Modify Wood Development to Cope with Drought

DOI: 10.1002/ppp3.29 REVIEW Wood and water: How trees modify wood development to cope with drought F. Daniela Rodriguez‐Zaccaro | Andrew Groover US Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station; Department of Plant Societal Impact Statement Biology, University of California Davis, Drought plays a conspicuous role in forest mortality, and is expected to become more Davis, California, USA severe in future climate scenarios. Recent surges in drought-associated forest tree Correspondence mortality have been documented worldwide. For example, recent droughts in Andrew Groover, US Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station; Department of California and Texas killed approximately 129 million and 300 million trees, respec- Plant Biology, University of California Davis, tively. Drought has also induced acute pine tree mortality across east-central China, Davis, CA, USA. Email: [email protected], agroover@ and across extensive areas in southwest China. Understanding the biological pro- ucdavis.edu cesses that enable trees to modify wood development to mitigate the adverse effects Funding information of drought will be crucial for the development of successful strategies for future for- USDA AFRI, Grant/Award Number: 2015- est management and conservation. 67013-22891; National Science Foundation, Grant/Award Number: 1650042; DOE Summary Office of Science, Office of Biological and Drought is a recurrent stress to forests, causing periodic forest mortality with enor- Environmental Research, Grant/Award Number: DE-SC0007183 mous economic and environmental costs. Wood is the water-conducting tissue of tree stems, and trees modify wood development to create anatomical features and hydraulic properties that can mitigate drought stress. This modification of wood de- velopment can be seen in tree rings where not only the amount of wood but also the morphology of the water-conducting cells are modified in response to environmental conditions.