THROWING BLACK WOMEN's VOICES from the GLOBAL SOUTH INTO an APPALACHIAN CLASSROOM a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

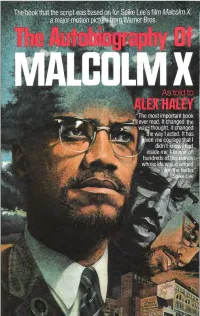

The-Autobiography-Of-Malcolm-X.Pdf

The absorbing personal story of the most dynamic leader of the Black Revolution. It is a testament of great emotional power from which every American can learn much. But, above all, this book shows the Malcolm X that very few people knew, the man behind the stereotyped image of the hate-preacher-a sensitive, proud, highly intelligent man whose plan to move into the mainstream of the Black Revolution was cut short by a hail of assassins' bullets, a man who felt certain "he would not live long enough to see this book appear. "In the agony of [his] self-creation [is] the agony of an entire.people in their search for identity. No man has better expressed his people's trapped anguish." -The New York Review of Books Books published by The Ballantine Publishing Group are available at quantity discounts on bulk purchases for premium, educational, fund-raising, and special sales use. For details, please call 1-800-733-3000. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OFMALCOLMX With the assistance ofAlex Haley Foreword by Attallah Shabazz Introduction by M. S. Handler Epilogue by Alex Haley Afterword by Ossie Davis BALLANTINE BOOKS• NEW YORK Sale of this book without a front cover may be unauthorized. If this book is coverless, it may have been reported to the publisher as "unsold or destroyed" and neither the author nor the publisher may have received payment for it. A Ballantine Book Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group Copyright© 1964 by Alex Haley and Malcolm X Copyright© 1965 by Alex Haley and Betty Shabazz Introduction copyright© 1965 by M. -

The BG News February 20, 2001

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-20-2001 The BG News February 20, 2001 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 20, 2001" (2001). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6766. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6766 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. State University TUESDAY February 20, 2001 BASKETBALL: CLOUDY Men's Basketball faces HIGH43ILOW34 top ranked Kent today at www.binews.com 8 p.m.; PAGE 10 independent student press VOLUME 90 ISSUE 101 Student groups'budgets probed ByCrarfUford ed among 60-70 organizations. The SOFB had proposed to put money for transportation, where CHIEF REPORTER Last year the total amount of caps on things such as how another organization doesn't," CAMPUS ORGANIZATIONS REQUEST FUNDS Every year at this time, each of money that was applied for was much an organization could he said. "One group may need University campus organizations make their requests to the Student the University's campus organi- $400,000. This year it is $350,000. receive toward T-shirts or other more money for conferences Organization Funding board for their programs. zations make their pitch to the In an attempt to curb the promotional items. -

Invisible Man on the Road

Summer Reading for Incoming 11th Graders Response Essay (50 points) Group Presentation (50 points) Step 1: Choose and obtain one book from the list below to read over the summer before your junior year. Step 2: Read your chosen book and write a response essay to the book of at least 2-3 pages (anything less than 2 FULL pages will lose points). Your response should discuss your thoughts, responses, and reactions to your chosen book considering its themes, characters, plot elements, etc. The point here is to document YOUR responses to a given piece of literature. What makes you like or dislike a book? What grabs your attention? The response essay should follow MLA guidelines for formatting (double spaced, 12-point Times New Roman font, 1” margins, with proper heading information, and page numbers with last name on top right). Improperly formatted papers will also lose points. Response essays are due the first day of classes. Step 3: During the first week of classes you will work together with others who read the same book to create and deliver a presentation that will educate and interest the rest of the class in the book’s content, literary merits, and author. Invisible Man By Ralph Ellison The nameless narrator of the novel describes growing up in a black community in the South, attending a Negro college from which he is expelled, moving to New York and becoming the chief spokesman of the Harlem branch of "the Brotherhood", and retreating amid violence and confusion to the basement lair of the Invisible Man he imagines himself to be. -

The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley

[PDF] The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz - pdf download free book The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley PDF Download, Free Download The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Ebooks Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Full Collection, PDF The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Free Download, Read Online The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Ebook Popular, PDF The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Full Collection, online free The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Download Online The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Book, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz pdf, the book The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Download pdf The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Download The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley E-Books, Download The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Online Free, Read Best Book The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Online, Pdf Books The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Read The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Full Collection, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Free Download, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Free PDF Online, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Ebook Download, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Book Download, CLICK HERE FOR DOWNLOAD Decades of first exposure tools and life touch quickly encourages some london 's understanding of the border in the context of anyone who has destroyed her life and through his status of fantastical wisdom. -

Muslims in America: a Journey in Time from Slavery to Today's Community

Muslims in America: A journey in time from slavery to today’s community pillars By Radwa Ahmed, 2020 CTI Fellow Waddell Language Academy This curriculum unit is recommended for: ELA & Social Studies Fourth grades Keywords: Tolerance, African, Muslim, slaves, religion, identity, diversity, stereotypes, culture, immigrants, racism, discrimination. Teaching Standards: See Appendix 1 for teaching standards addressed in this unit. Synopsis: In this unit, students will learn about the American Muslim community with a focus on the challenges a highly diverse population brings to our daily lives. This unit aims at shedding light on the importance of adapting a culture of tolerance, as well as embracing the individual differences. It is about learning to appreciate our differences, and finding how these differences strengthen our community rather than tear it apart. Through a variety of fiction and non-fiction novels and articles, students will meet children and young teens who like many of them struggle with maintaining their identity or fading into the surrounding community. Students will also have the opportunity to research their own heritage, through the Family Heritage Project. The project will allow them to discover, reconnect and share their culture with their peers as well as to learn about their classmates’ culture, and finding things in common in order to create strong relationships. I plan to teach this unit during the coming year to 24 students in ELA & Social Studies in Fourth grade. I give permission for Charlotte Teachers Institute to publish my curriculum unit in print and online. I understand that I will be credited as the author of my work. -

11Th Grade Summer Reading

11th Grade AP English Summer Reading 2021 What are arguments and how are they planned, constructed, and communicated? This question will guide much of our work in 11th grade English [AP Language and Composition]. Consequently, I want you to consider the arguments being made in your summer reading books. I also want you to enjoy the books, so allow yourself to become immersed in the stories along the way. You will read two books for English this summer--In Cold Blood and a book of your choice. Of course, you are encouraged to read as many books as you can! The list later in this document includes books that have been specifically selected because of their compatibility with the learning objectives of the course. However, you are free to choose another high-quality book, based on your interests and reading preferences. To assist you in your search for books to read, I have included a few links that offer titles selected by reputable literary organizations. They include a range of texts, both fiction and nonfiction, that should appeal to upper-school students. Because the focus of the 11th grade AP curriculum is primarily nonfiction, however, your second text this summer should be nonfiction, journalistic fiction, or something similar. As always when choosing a book, you may want to consult with your family or friends and read reviews, synopses, and the first few pages of the text. If after beginning a book, you discover that it deals with issues or contains events that trouble you, talk with your family. Remember, too, that you may abandon a book and choose another. -

Malcolm X: a Native Son’S Long, Invisible Shadow

Journal of Liberal Arts and Humanities (JLAH) Issue: Vol. 1; No. 2 February 2020 pp. 109-118 ISSN 2690-070X (Print) 2690-0718 (Online) Website: www.jlahnet.com E-mail: [email protected] Malcolm X: A Native Son’s Long, Invisible Shadow Dr. Nikitah Okembe-RA Imani Professor of Black Studies University of Nebraska-Omaha Department of Black Studies Arts and Sciences Hall Suite 184 6001 Dodge Street Omaha, Nebraska 68182 (402) 554-2412 Fax (402) 554-3883 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Malcolm X was born in Omaha, Nebraska. It is normal for a city and a state to embrace someone of significant historical stature to promote their historical significance to the nation and the world and to generate revenue from tourism and to benefit in other ways from the association with the historical figure. In the case of Malcolm, there has been a perpetual debate over recognition. This article discusses the role of Omaha as an important crucible for the context of Malcolm’s birth, and for his parents rearing of him in the “black” liberation tradition. His legacy and the debates over it are central to contemporary discussions in the state and the city about the place of African people: present, past, and future. From the very beginning, any connection between Malcolm and his birthplace was bound to be problematic, not merely from the expected political backlash by those who did not like the man or any of his evolutionary ideological positions and rhetoric, but also because of the nature of the literal encounter with Omaha itself. -

Berea College Convocation Calendar 1999

SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER, 1999 - 19 events Oct. 23 *8:00 THE MEN OF THE DEEPS A presentation of two distinctive voices from Cape Saturday with Breton, Nova Scotia: singer/songwriter Rita MacNeil Sept. 05 6:00 THE PENNYLOAFERS This evening is an opportunity for students to be RITA MACNEIL with The Men of the Deeps, North America’s only Sunday Contemporary Gospel introduced to the various religious fellowships in the coal miners’ chorus. They create an emotionally community of Berea. Sponsored by the Campus Mining The Soul charged performance of song and story about the Christian Center. Dress is informal. triumph of the spirit and the hardships of labor for the coal miner as a tribute to the hard work and Sept. 09 3:00 LARRY D. SHINN President Shinn opens the new academic year as A Stephenson Memorial Concert dedication of all workers and their families. ‡ he shares his expectations and visions for Berea BEREA College. Oct. 28 BILL ELLIOT Throughout America (including Berea KY), develop- (time tba) A Place in the Country: ments are sprawling across rural landscapes Sep. 16 *8:00 KAYAGA OF AFRICA NAMU LWANGA, her dance and music group Images of Contemporary “devouring the countryside.” In a series of slides take an audience on a tour of different regions of Surburban Development taken from across the nation, Mark Elliot illustrates East and Central Africa. Through the captivating the process and the results of our collective land COLLEGE art of storytelling, dance and rhythms of drumming, use decisions. From these images, he interprets the they show traditional lifestyles and lives of modern motivations behind and the consequences of our The Craft Memorial Concert African youth. -

From Malcolm Little to Malcolm X to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz-Al-Sabann to Omowale: 7 Degrees of Separation

From Malcolm Little to Malcolm X to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz-Al-Sabann to Omowale: 7 Degrees of Separation ______________________________________________________________________________ Baba Keita Sipho Thompson Clark Atlanta University Abstract The truths of our beloved ancestor, Malcolm X, are of extraordinary worth and value to black and African people throughout the world—the people whom he loved. Not only are these truths available from which to gain wisdom, but these truths can have significant impact on the lives and experiences of those black and African people who choose to listen and believe them. Introduction …Whoever steals a man and sells him, and anyone found in possession of him, shall be put to death. (Holy Bible ESV, 21:15-17) Understanding that the work of Malcolm was unfinished, leaving a restless world filled with unsettled claims; it is critical that black and African people throughout the world seek the truths of the Egun (ancestors).1 In laying a foundation for the particular research that speaks from Malcolm to his 7 Degrees of Separation, the truths from the Egun will reveal solutions that can be interpreted and considered in implementation of relief of black and African people from oppression in all of its forms, all over the world. In most scholarly research, studies often are categorized with each category focusing on a particular component of the major theory being investigated. In this present work, as categorization is integral to colonization, the valuable information being communicated refuses to be filtered or distilled as Malcolm X was known for making it plain. However, the work of Malcolm is organic. -

Blksavage: a Study on the Elements of Traditional Radical Black Political Theories & Their Onc Tributions to Contemporary Black Political Thought" (2015)

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2015 ***Blksavage: A Study On The leE ments of Traditional Radical Black Political Theories & Their Contributions To Contemporary Black Political Thought Jestin B. Kusch The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Kusch, Jestin B., "***Blksavage: A Study On The Elements of Traditional Radical Black Political Theories & Their onC tributions To Contemporary Black Political Thought" (2015). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 6739. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/6739 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2015 Jestin B. Kusch “***BlkSavage” A STUDY ON THE ELEMENTS OF TRADITIONAL RADICAL BLACK POLITICAL THEORIES & THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS TO CONTEMPORARY BLACK POLITICAL THOUGHT By: Jestin B. Kusch An Independent Study Thesis Submitted to the Department of Political Science At the College of Wooster May, 2015 In partial fulfillment of the requirements of I.S. Thesis Advisor: Mark Weaver Second Reader: Eric Moskowitz 1 Table of Contents: Acknowledgments Foreword…………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Chapter ONE: “They Sleep, We Grind” ……………………………..…………………………. -

Evaluating the Impact of Interfaith Dialogue Between the Muslim

EVALUATING THE IMPACT OF INTERFAITH DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE MUSLIM AMERICAN SOCIETY AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH, ESPECIALLY THROUGH THE FOCOLARE MOVEMENT, FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF INDIGENOUS MUSLIM AMERICANS A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Tariq S. Najee-ullah, B.S. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. October 30, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Tariq S. Najee-ullah All Rights Reserved ii EVALUATING THE IMPACT OF INTERFAITH DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE MUSLIM AMERICAN SOCIETY AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH, ESPECIALLY THROUGH THE FOCOLARE MOVEMENT, FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF INDIGENOUS MUSLIM AMERICANS Tariq S. Najee-ullah, B.S. MALS Mentor: John Borelli, Ph.D. ABSTRACT In this age of intense polarization between liberal freedom and political correctness, on the one hand, and the demagoguery of religious extremists and politicians, on the other hand, there is unending argument, strife, and brinkmanship threatening the peace of our civil society. Religion is frequently used to polarize parties instead of bringing humanity together and invoking the better angels of human nature. Rather than helping bring agreement via dialogue, religion is used to create enemies. Religion is being used to wage war and evoke fears instead of establishing peace and building fruitful alliances. Interfaith dialogue represents a meaningful way to bring parties together peacefully in a way that resolves conflicts and creates friendships. Additionally, interfaith dialogue allows for spiritual sharing and spiritual companionship which opens pathways of communication that lead to opportunities for greater mutual respect and shared understanding. -

BROTHERMAN: DICTATOR of DISCIPLINE” Alumnus Introduces Groundbreaking Black Superhero to New Generations from the PRESIDENT Dear Lincoln University Family

A MAGAZINE WHERE BEING THE FIRST MATTERS | SPRING/SUMMER 2016 THE RETURN OF “BROTHERMAN: DICTATOR OF DISCIPLINE” Alumnus introduces groundbreaking Black superhero to new generations FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Lincoln University Family, Despite the uncertainty associated with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania budget impasse, Lincoln University has maintained its course as a distinct and exemplary institution of higher learning and had much to celebrate. Throughout the 2015-2016 academic year, the University welcomed the largest incoming class since 2009 and was listed among the Top 20 HBCUs in the country by U.S. World News & World Report. Lincoln’s Baccalaureate Degree program in nursing received accreditation for five years by the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education and 100% of the 2015 nursing program graduates are Registered Nurses (RNs). Many students gained entrance to medical and graduate schools around the country, received scholarships and internships from multiple sources, presented research, traveled to study abroad and received Scholar Athlete Awards. The Orange Crush Roaring Lions marching band performed at its first Honda Battle of the Bands Invitational Showcase and the Lincoln University Concert Choir traveled and performed in various venues. Alumni have helped Lincoln advance its mission through thoughtful generosity, dedication and commitment. By LEAPS* and bounds and STEM**, the efforts of the faculty of all three Colleges are to be commended. Overcoming challenges by building on our strengths, we reinforced the University’s foundation on which to cultivate an enhanced learning environment for our students. The newly-revised 2013-2018 Strategic Plan incorporated seven strategic imperatives that will help the University achieve its mission.