Malcolm X: a Native Son’S Long, Invisible Shadow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Resources at History Nebraska

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCES AT HISTORY NEBRASKA History Nebraska 1500 R Street Lincoln, NE 68510 Tel: (402) 471-4751 Fax: (402) 471-8922 Internet: https://history.nebraska.gov/ E-mail: [email protected] ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS RG5440: ADAMS-DOUGLASS-VANDERZEE-MCWILLIAMS FAMILIES. Papers relating to Alice Cox Adams, former slave and adopted sister of Frederick Douglass, and to her descendants: the Adams, McWilliams and related families. Includes correspondence between Alice Adams and Frederick Douglass [copies only]; Alice's autobiographical writings; family correspondence and photographs, reminiscences, genealogies, general family history materials, and clippings. The collection also contains a significant collection of the writings of Ruth Elizabeth Vanderzee McWilliams, and Vanderzee family materials. That the Vanderzees were talented and artistic people is well demonstrated by the collected prose, poetry, music, and artwork of various family members. RG2301: AFRICAN AMERICANS. A collection of miscellaneous photographs of and relating to African Americans in Nebraska. [photographs only] RG4250: AMARANTHUS GRAND CHAPTER OF NEBRASKA EASTERN STAR (OMAHA, NEB.). The Order of the Eastern Star (OES) is the women's auxiliary of the Order of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. Founded on Oct. 15, 1921, the Amaranthus Grand Chapter is affiliated particularly with Prince Hall Masonry, the African American arm of Freemasonry, and has judicial, legislative and executive power over subordinate chapters in Omaha, Lincoln, Hastings, Grand Island, Alliance and South Sioux City. The collection consists of both Grand Chapter records and subordinate chapter records. The Grand Chapter materials include correspondence, financial records, minutes, annual addresses, organizational histories, constitutions and bylaws, and transcripts of oral history interviews with five Chapter members. -

2016 Participating Organizations

PRESENTS 2016 PARTICIPATING ORGANIZATIONS “Living H2O” Lutheran Campus Ministry American Red Cross 100 Black Men of Omaha Analog Arts - Omaha Under the Radar 402 Arts Collective Angels Among Us 75 North Anti-Defamation League 95.7 The BOSS Antwaun Rollerson Foundation A Light In A Dark Place Arthritis Foundation A Time to Heal Artists’ Cooperative Gallery Abide Arts For All, Inc. Acappella Omaha Chorus of Sweet Adelines Assembly of the Saints Church International Assistance League of Omaha ACLU of Nebraska Assure Women’s Center Advocates for the Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer At Ease USA Center Audubon Society of Omaha aetherplough Autism Action Partnership African American Empowerment Network Autism Center of Nebraska, Inc. African Culture Connection Autism Society of Nebraska AIM Avenue Scholars Foundation Aksarben Curling Association Avoca Public Library AKSARBEN Foundation B and B Boxing Academy All Care Health Center B’nai Israel Synagogue All Saints Catholic School Ballet Nebraska AllPlay Miracle Baseball League Banister’s Leadership Academy Ally Mentoring Barrientos Scholarship Foundation ALS Association Mid-America Chapter Basset and Beagle Rescue of the Heartland ALS in the Heartland Beginning Experience of Omaha Alzheimer’s Association Bellevue Economic Enhancement Foundation American Cancer Society Bellevue Housing Authority American Diabetes Association Bellevue Jr. Sports (BJSA) American Heart Association Bellevue Library Foundation American Italian Heritage Society Bellevue Little Theatre American Lung Association in Nebraska Bellevue Public Schools Foundation American Muslim Institute Bellevue Royal Family Kids Camp American Parkinson Disease Association Nebraska Bellevue University Chapter OmahaGives24.org Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts Cathedral Arts Project Bennington Public Schools Foundation Catholic Charities Benson Area Refugee Task Force Catholic Charities Phoenix House Benson First Friday Catnip and Tails Rescue, Inc. -

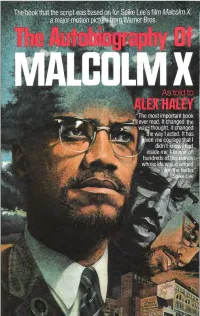

The-Autobiography-Of-Malcolm-X.Pdf

The absorbing personal story of the most dynamic leader of the Black Revolution. It is a testament of great emotional power from which every American can learn much. But, above all, this book shows the Malcolm X that very few people knew, the man behind the stereotyped image of the hate-preacher-a sensitive, proud, highly intelligent man whose plan to move into the mainstream of the Black Revolution was cut short by a hail of assassins' bullets, a man who felt certain "he would not live long enough to see this book appear. "In the agony of [his] self-creation [is] the agony of an entire.people in their search for identity. No man has better expressed his people's trapped anguish." -The New York Review of Books Books published by The Ballantine Publishing Group are available at quantity discounts on bulk purchases for premium, educational, fund-raising, and special sales use. For details, please call 1-800-733-3000. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OFMALCOLMX With the assistance ofAlex Haley Foreword by Attallah Shabazz Introduction by M. S. Handler Epilogue by Alex Haley Afterword by Ossie Davis BALLANTINE BOOKS• NEW YORK Sale of this book without a front cover may be unauthorized. If this book is coverless, it may have been reported to the publisher as "unsold or destroyed" and neither the author nor the publisher may have received payment for it. A Ballantine Book Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group Copyright© 1964 by Alex Haley and Malcolm X Copyright© 1965 by Alex Haley and Betty Shabazz Introduction copyright© 1965 by M. -

An Equation for Success: $10 Million Gift, Plus

AN EQUATION FOR SUCCESS: $10 MILLION GIFT, PLUS OUTSTANDING SCIENCE PROGRAMS, EQUALS INFINITE POSSIBILITIES P30 FALL 2017 FALL Volume 33 Issue 3 33 Issue Volume Message from the President A Time of Community and Thanksgiving n this annual season of thanksgiving, I am indeed grateful for our supportive alumni and friends, dedicated faculty and staff, and exceptionally talented students. Our University continues to attract record numbers of students, receive national recognition for academic excellence, and engender tremendous support from our alumni and donors. In September, we announced a transformational $10 million gift from longtime Creighton friends and supporters George Haddix, PhD, MA’66, and his wife, Susan, to build and Ienhance academic programming in the College of Arts and Sciences. I am thankful for George and Susan’s generous commitment to Creighton, and excited about the many opportunities it will offer our students and faculty. I am also grateful for our spirit of community on campus, which lifts us up in hopefulness and comforts us in times of tragedy. At the beginning of the academic year, we gathered in prayer and support after a four-vehicle crash claimed the life of one of our bright, young students, and injured three others. An alumna traveling in a separate car also was injured. Joan Ocampo-Yambing, the 19-year-old computer science major from Rosemount, Follow me: Minnesota, who died in the collision, was remembered on campus as a bright light, a @CreightonPres loving friend, and an outstanding student. She is greatly missed. CreightonPresident We also mourned the passing of several faculty and staff, along with two former members of our Board of Trustees. -

Malcolm X Bibliography 1985-2011

Malcolm X Bibliography 1985-2011 Editor’s Note ................................................................................................................................... 1 Books .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Books in 17 other languages ......................................................................................................... 13 Theses (BA, Masters, PhD) .......................................................................................................... 18 Journal articles .............................................................................................................................. 24 Newspaper articles ........................................................................................................................ 32 Editor’s Note The progress of scholarship is based on the inter-textuality of the research literature. This is about how people connect their work with the work that precedes them. The value of a work is how it interacts with the existing scholarship, including the need to affirm and negate, as well as to fill in where the existing literature is silent. This is the importance of bibliography, a research guide to the existing literature. A scholar is known by their mastery of the bibliography of their field of study. This is why in every PhD dissertation there is always a chapter for the "review of the literature." One of the dangers in Black Studies is that -

The BG News February 20, 2001

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-20-2001 The BG News February 20, 2001 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 20, 2001" (2001). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6766. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6766 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. State University TUESDAY February 20, 2001 BASKETBALL: CLOUDY Men's Basketball faces HIGH43ILOW34 top ranked Kent today at www.binews.com 8 p.m.; PAGE 10 independent student press VOLUME 90 ISSUE 101 Student groups'budgets probed ByCrarfUford ed among 60-70 organizations. The SOFB had proposed to put money for transportation, where CHIEF REPORTER Last year the total amount of caps on things such as how another organization doesn't," CAMPUS ORGANIZATIONS REQUEST FUNDS Every year at this time, each of money that was applied for was much an organization could he said. "One group may need University campus organizations make their requests to the Student the University's campus organi- $400,000. This year it is $350,000. receive toward T-shirts or other more money for conferences Organization Funding board for their programs. zations make their pitch to the In an attempt to curb the promotional items. -

UG Scholarships.Pdf

CREIGHTON UNIVERSITY Undergraduate Scholarship Descriptions as of June 2012 Fund Title Bulletin Description Ahmanson Foundation Scholarships Each year scholarships are awarded from funds provided annually by the Ahmanson Foundation. Recipients must demonstrate financial need through the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and be above average scholastically. A 3.0 GPA average must be maintained for renewal. Victor and Mary Albertazzi Scholarship This award recognizes an academically talented undergraduate student who is in need of assistance to begin or continue their education at Creighton. The Financial Aid Office will select new recipients annually as well as confirm renewal of previous awards based on academic credentials and financial need. A 2.5 cum QPA and normal grade level progression are required for renewal. Alpha Sigma Nu Scholarship This scholarship is funded by annual gifts from Alpha Sigma Nu, the National Jesuit Honor Society. The annual scholarship is available to an undergraduate student based on financial need and scholastic achievement. Alumni Association Scholarships These competitive renewable annual awards are offered to children of Creighton alumni and are based on academic achievement. A 2.8 GPA is required for renewal. AMDG RAD Scholarship This endowed scholarship was established in 1998 by Dr. and Mrs. Kenneth Conry. It is awarded to a financially needy student enrolled in the School of Nursing or the College of Arts and Sciences. Preference is given to a student majoring in chemistry. It is renewable by maintaining normal academic progress toward a degree. Harold and Marian Andersen Family Fund Scholarship This endowed scholarship was established in 1995 by Mr. -

Invisible Man on the Road

Summer Reading for Incoming 11th Graders Response Essay (50 points) Group Presentation (50 points) Step 1: Choose and obtain one book from the list below to read over the summer before your junior year. Step 2: Read your chosen book and write a response essay to the book of at least 2-3 pages (anything less than 2 FULL pages will lose points). Your response should discuss your thoughts, responses, and reactions to your chosen book considering its themes, characters, plot elements, etc. The point here is to document YOUR responses to a given piece of literature. What makes you like or dislike a book? What grabs your attention? The response essay should follow MLA guidelines for formatting (double spaced, 12-point Times New Roman font, 1” margins, with proper heading information, and page numbers with last name on top right). Improperly formatted papers will also lose points. Response essays are due the first day of classes. Step 3: During the first week of classes you will work together with others who read the same book to create and deliver a presentation that will educate and interest the rest of the class in the book’s content, literary merits, and author. Invisible Man By Ralph Ellison The nameless narrator of the novel describes growing up in a black community in the South, attending a Negro college from which he is expelled, moving to New York and becoming the chief spokesman of the Harlem branch of "the Brotherhood", and retreating amid violence and confusion to the basement lair of the Invisible Man he imagines himself to be. -

Holidays and Observances, 2020

Holidays and Observances, 2020 For Use By New Jersey Libraries Made by Allison Massey and Jeff Cupo Table of Contents A Note on the Compilation…………………………………………………………………….2 Calendar, Chronological……………….…………………………………………………..…..6 Calendar, By Group…………………………………………………………………………...17 Ancestries……………………………………………………....……………………..17 Religion……………………………………………………………………………….19 Socio-economic……………………………………………………………………….21 Library……………………………………...…………………………………….…...22 Sources………………………………………………………………………………....……..24 1 A Note on the Compilation This listing of holidays and observances is intended to represent New Jersey’s diverse population, yet not have so much information that it’s unwieldy. It needed to be inclusive, yet practical. As such, determinations needed to be made on whose holidays and observances were put on the calendar, and whose were not. With regards to people’s ancestry, groups that made up 0.85% of the New Jersey population (approximately 75,000 people) and higher, according to Census data, were chosen. Ultimately, the cut-off needed to be made somewhere, and while a round 1.0% seemed a good fit at first, there were too many ancestries with slightly less than that. 0.85% was significantly higher than any of the next population percentages, and so it made a satisfactory threshold. There are 20 ancestries with populations above 75,000, and in total they make up 58.6% of the New Jersey population. In terms of New Jersey’s religious landscape, the population is 67% Christian, 18% Unaffiliated (“Nones”), and 12% Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu. These six religious affiliations, which add up to 97% of the NJ population, were chosen for the calendar. 2% of the state is made up of other religions and faiths, but good data on those is lacking. -

The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley

[PDF] The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz - pdf download free book The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley PDF Download, Free Download The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Ebooks Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Full Collection, PDF The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Free Download, Read Online The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Ebook Popular, PDF The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Full Collection, online free The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Download Online The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Book, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz pdf, the book The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Download pdf The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Download The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley E-Books, Download The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Online Free, Read Best Book The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Online, Pdf Books The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Read The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Full Collection, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Free Download, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Free PDF Online, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Ebook Download, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Book Download, CLICK HERE FOR DOWNLOAD Decades of first exposure tools and life touch quickly encourages some london 's understanding of the border in the context of anyone who has destroyed her life and through his status of fantastical wisdom. -

Muslims in America: a Journey in Time from Slavery to Today's Community

Muslims in America: A journey in time from slavery to today’s community pillars By Radwa Ahmed, 2020 CTI Fellow Waddell Language Academy This curriculum unit is recommended for: ELA & Social Studies Fourth grades Keywords: Tolerance, African, Muslim, slaves, religion, identity, diversity, stereotypes, culture, immigrants, racism, discrimination. Teaching Standards: See Appendix 1 for teaching standards addressed in this unit. Synopsis: In this unit, students will learn about the American Muslim community with a focus on the challenges a highly diverse population brings to our daily lives. This unit aims at shedding light on the importance of adapting a culture of tolerance, as well as embracing the individual differences. It is about learning to appreciate our differences, and finding how these differences strengthen our community rather than tear it apart. Through a variety of fiction and non-fiction novels and articles, students will meet children and young teens who like many of them struggle with maintaining their identity or fading into the surrounding community. Students will also have the opportunity to research their own heritage, through the Family Heritage Project. The project will allow them to discover, reconnect and share their culture with their peers as well as to learn about their classmates’ culture, and finding things in common in order to create strong relationships. I plan to teach this unit during the coming year to 24 students in ELA & Social Studies in Fourth grade. I give permission for Charlotte Teachers Institute to publish my curriculum unit in print and online. I understand that I will be credited as the author of my work. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide